- 302 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

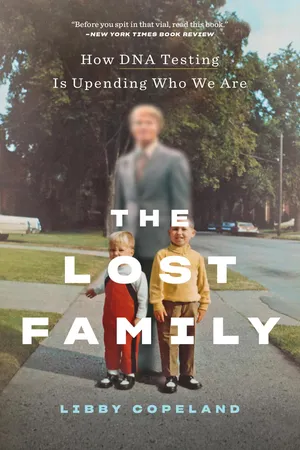

About this book

"A fascinating exploration of the mysteries ignited by DNA genealogy testing—from the intensely personal and concrete to the existential and unsolvable." —Tana French,

New York Times–bestselling author

You swab your cheek or spit in a vial, then send it away to a lab somewhere. Weeks later you get a report that might tell you where your ancestors came from or if you carry certain genetic risks. Or, the report could reveal a long-buried family secret that upends your entire sense of identity. Soon a lark becomes an obsession, a relentless drive to find answers to questions at the core of your being, like "Who am I?" and "Where did I come from?" Welcome to the age of home genetic testing.

In The Lost Family, journalist Libby Copeland investigates what happens when we embark on a vast social experiment with little understanding of the ramifications. She explores the culture of genealogy buffs, the science of DNA, and the business of companies like Ancestry and 23andMe, all while tracing the story of one woman, her unusual results, and a relentless methodical drive for answers that becomes a thoroughly modern genetic detective story. Gripping and masterfully told, The Lost Family is a spectacular book on a big, timely subject.

"An urgently necessary, powerful book that addresses one of the most complex social and bioethical issues of our time." —Dani Shapiro, New York Times–bestselling author

"Before you spit in that vial, read this book." — The New York Times Book Review

"Impeccably researched . . . up-to-the-minute science meets the philosophy of identity in a poignant, engaging debut." — Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

You swab your cheek or spit in a vial, then send it away to a lab somewhere. Weeks later you get a report that might tell you where your ancestors came from or if you carry certain genetic risks. Or, the report could reveal a long-buried family secret that upends your entire sense of identity. Soon a lark becomes an obsession, a relentless drive to find answers to questions at the core of your being, like "Who am I?" and "Where did I come from?" Welcome to the age of home genetic testing.

In The Lost Family, journalist Libby Copeland investigates what happens when we embark on a vast social experiment with little understanding of the ramifications. She explores the culture of genealogy buffs, the science of DNA, and the business of companies like Ancestry and 23andMe, all while tracing the story of one woman, her unusual results, and a relentless methodical drive for answers that becomes a thoroughly modern genetic detective story. Gripping and masterfully told, The Lost Family is a spectacular book on a big, timely subject.

"An urgently necessary, powerful book that addresses one of the most complex social and bioethical issues of our time." —Dani Shapiro, New York Times–bestselling author

"Before you spit in that vial, read this book." — The New York Times Book Review

"Impeccably researched . . . up-to-the-minute science meets the philosophy of identity in a poignant, engaging debut." — Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Lost Family by Libby Copeland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ethics in Medicine. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

ALICE IS NOT ALICE

The first thing Alice Collins Plebuch told me when she opened the door to her house was that I was tall. I am not tall.

Alice is very short. Five feet if she’s lucky, she likes to say. She’s in her early seventies, and her grandkids call her Grandma Nerd for her love of technology. Before we walked to her office-slash-sewing-room, she warned me not to take my shoes off, because sewing pins were scattered all over and I was likely to get them embedded in my feet. And then she led me back to her busy, treacherous, creative space, filled with bits of fabric and piles of books and genealogical research folders arranged so delicately that if you had the bad sense to reach for an object that looked interesting, a whole stack of things might come tumbling to the floor, and Alice might or might not notice, and might or might not say don’t worry, she’d get to it later.

Alice Collins Plebuch

She gave me a tour of her advanced sewing technology, so unlike standard sewing machines as to be an entirely different species. Atop one desk was something called THE Dream Machine 2 by Brother, a sewing, embroidery, quilting, and crafting machine so complex I’d been confounded each time Alice had tried to describe it to me over the phone. It was huge, with a ten-inch high-definition screen to choose an embroidery image and the capacity to scan and to plug in a memory stick so that you could add more. (It had been retailing for the cost of a Kia when she’d bought it a few years before, though Alice being Alice, she did not pay anywhere near that much.) Nearby were several other serious-looking contraptions, including something called a serger for executing what are known as overlock stitches, and something called an AccuQuilt, which I read is supposed to help you “reclaim your quilting joy.”

Then Alice showed me the things she’d made on these machines, the beauty of which I could comprehend. By her desk was an early effort saluting a book series she devoured long before HBO made it into television: a direwolf from Game of Thrones with the phrase “Winter is coming.” She showed me pictures of the fancy, full-body burgundy Star Trek costumes she’d made for herself, her eldest son, and his children, refashioning the complex rank braid each time her son told her it wasn’t quite faithful to the on-screen version. On the back of a denim jacket she’d crafted an elaborate, plaintive-looking green-and-gold dragon, studded with red and silver crystals, its one sad eye outlined in shiny nuggets of gold. Just now she was working on removable pillow covers for the cushions of her couch, using a patterned turquoise fabric she’d found on deep discount. She had plans and measurements sketched out, and throwaway cloth for playing with, and as she showed me her plans, she improvised, folding the cloth this way and that, looking for the design that offered the right fit and the right give. For Alice, sewing is not a tribute to domesticity; she tends to resent domesticity, given the way she was raised, the eldest girl in a family of nine. Rather, sewing is nerdy, technical, challenging. Alice loves a challenge.

Over the years, I’ve thought a lot about Alice’s brain—how for decades she honed certain skills involving technological efficiency and problem-solving, so that when the time came for her to answer the most important question of all, she dug in like she’d been training for it. When she was growing up, her family was not wealthy—no matter how many overtime shifts her dad worked, there were still seven kids to care for—so she put herself through college, washing dishes and tutoring kids in math and sewing her own clothes to save money. In time, she worked for a professor as a “keypuncher,” putting information onto computer cards to be fed into a mainframe computer, and quickly demonstrated what a college friend describes as “a natural feel” for crunching data on those finicky machines. She got a degree in political science at the University of California, Riverside, specializing in statistical analysis, and nearly finished a master’s degree in political science. In 1971, she married Bruce Plebuch, who studied philosophy in grad school and later became a lawyer. The same year, she got a job working as a clerk for the University of California, Santa Barbara.

There, Alice stumbled on a problem in need of solving. Faculty members’ records were on card files, and a small staff spent an inordinate amount of time tracking and updating their salaries and academic advancements. Alice had the idea to put this information onto early computers. This set a pattern, and became the focus of her career in a series of positions in the field of information systems and data processing throughout the University of California system, where she worked with personnel files, payroll systems, and benefits enrollment, facets of working life that most of us notice only when they’re clunky and broken. Early on, Alice was part of a rising cadre of women in a male-dominated environment. She asked her boss for a title and salary to match her responsibilities—“You know if you had a man doing this you’d be paying him a lot more”—and got the first of many promotions.

And she kept making suggestions for how things could be better. It sure would be a lot nicer if we had these automated. And, when the Internet came along: It sure would be cool if people could access their benefits online. All that data could be put to better use if only someone were willing to tame it, and Alice was just the woman for the job. “I’m not intimidated by lots of data,” she told me. She’d always been good at math and science; as a kid, if a problem stumped her, she’d go to sleep and wake up with the answer. She can see the big picture, but she also notices the details. She told me it used to piss off one of her programmers, the way she could scroll through acres of his work and glimpse the one error that would mean a whole program wouldn’t work. She could do it quickly, by picking out the “nits.”

Alice has been retired for many years. She stopped working in her late fifties, the result of financial planning and good retirement benefits. But she remained an early adopter of new technologies. In 2007, before anyone had an iPhone, she flew to the Macworld Expo in San Francisco to cradle the prototype in her arms. She had the first model the very day it became available, and still does with every new iPhone. And when the thing happened that set everything into motion and changed Alice’s life, this was also the result of her love of new technologies. Alice being Alice, she could not leave a puzzle unsolved, no matter how difficult it was or how troubling its implications.

She could not.

* * *

Alice had long had questions about her family. Her mother, who was also named Alice, was into genealogy and kept an old family bible from the 1840s with birth, death, and marriage notations that traced back her English roots. Alice the elder had encouraged her daughter to embrace her hobby. But sometimes daughters want to do the opposite of what their mothers tell them, which is why Alice the younger refused to indulge whatever nascent interest she had in the topic until after her mom died in 1992.

Then, she dove in. Alice found her mother’s line easy to document, even in the years before lots of genealogical records were online. Her mom, Alice Nisbet Collins, was descended from Irish people on one side, and on the other from Scottish and English people, some of whom had been on this side of the Atlantic as far back as colonial America. Alice was able to follow one line of her mother’s ancestors back to 1500s England. Alice’s father, Jim, lived for seven years after his wife died, and as Alice updated him on everything she was finding along her mother’s line, she began to feel guilty. “Because my dad had nothing—he had no history,” she says.

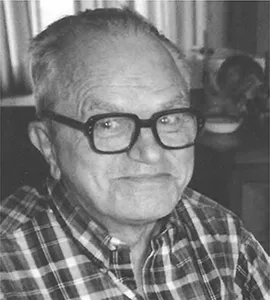

Alice’s father, Jim Collins

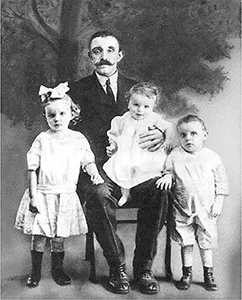

Jim Collins, the son of Irish immigrants, knew little of his parents, one of whom he barely remembered and the other not at all. His mother had died when he was a baby, and his father had given him and his older siblings away to a Catholic orphanage. For a long time, Jim didn’t even know what year he was born; sending away for some vitals as a young man, he’d discovered he was a year younger than he’d thought. So, in her father’s waning years, Alice dove into the project of Jim. She had just one image of him as a child, taken in 1914, shortly before he and his siblings were sent away. In the photo, curly-haired Jim sits on his father’s lap, clad in a white baby dress, with his tiny sister and brother standing on either side. He is the only one smiling.

The Collins children, Kitty, Jim, and John, with their father, John Josef

Some things Alice already knew. She knew that life in the orphanage had been difficult. She knew her dad was probably malnourished there, because a doctor later told Jim that this likely explained his small stature. She knew that Jim had left the orphanage as a young teenager, and that he’d lived some rowdy years he liked to describe as his “misspent youth,” before he joined the Civilian Conservation Corps and then the US Army Corps of Engineers, and met and married Alice’s mother. She knew Jim had loved his sister, who died as a young woman, and had not been close to his brother.

Alice and her siblings sensed that Jim’s Irishness and his Catholicism were important to him; they were what was left of his identity when so much else was taken away. He cooked a wicked corned beef on St. Patrick’s Day, and liked to brag to one of his granddaughters about the time someone had described him as a “thoroughbred Irishman.” Jim and Alice the elder had five boys and two girls, and the family went to church on Sundays, and much of the kids’ schooling was at Catholic schools, and it was “important to him that the kids be raised Catholic,” says Alice’s sister, Gerardine Collins Wiggins, who goes by Gerry. But for all that, Jim’s knowledge of his roots was shallow. He knew his dad was from County Cork. Before traveling to Ireland in 1990, Gerry had sent away for Jim’s birth certificate, hoping it would help her trace his roots. But when she arrived in Ireland with the document and the few family names her dad was able to give her, the office she’d planned to consult for historical resources had closed down, and Gerry couldn’t search the old records. Looking back, there were several moments like that: moments when questions were asked but answers were not forthcoming, when the paucity of information available to Jim fastened riddles into tight knots.

Here’s another. Jim was not terribly knowledgeable about his extended family, and they seem not to have embraced him, either in childhood, when he might have needed them most, or later. But in adulthood, Jim tracked down an aunt while traveling in the Southwest, and went into the hotel she was running to inquire if he could visit with her. He could hear her informing someone that she was taking her nap and that her nephew would have to come back later. He left, hurt, and never met with his aunt, and any questions he might have had about the mysteries of his childhood and the parents he barely remembered and the extended family who didn’t take in those three kids bound for an orphanage—those questions went unasked.

When Alice embarked on her genealogical quest on behalf of her father, she knew it would not be nearly as easy as it had been for her mother, but that was OK. Alice likes research. She sent away for Jim’s parents’ death certificates and headed over to the National Archives in San Francisco, where she was living at the time, to comb through microfilm, looking for her grandparents in the 1910 census. She was surprised by how little she knew about Jim. At one point, she realized she didn’t even know his mother’s proper first name.

She was able to glean just the barest outline of her father’s parents. When Jim was born, his family lived in a working-class neighborhood in the Bronx. His father, John Josef Collins, was listed as a “driver” and later a longshoreman. His mother, Katie, died at thirty-two, when little Jim was just nine months old. When Alice got her grandmother Katie’s death certificate, she strained to read the words by cause of death, which were written in the kind of loopy, inscrutable script that is the bane of every genealogist’s existence. She thought it read, in part, “cranial softening” or “cerebral softening”; she showed it to a pathologist friend, who thought Katie might have had encephalitis. The last word, though, was absolutely clear. It said “insanity.” How, Alice wondered, does a person die of insanity?

Before Jim died in 1999, just before his eighty-sixth birthday, Alice wasn’t able to tell him much more than he already knew. And in the years that followed, she continued to be stymied by the paper trail. Searching census records, she managed to figure out the name of the orphanage in Sparkill, New York, where Jim had spent his childhood. It had been called St. Agnes Home and School, though the orphanage itself no longer existed by the time Alice found it. She wrote the religious sisters located there, asking for information on her dad and his parents, and got back a letter with the barest of facts: the date Jim and his siblings were admitted, and the varying dates when he and his siblings were discharged.

Before many Americans were aware of the way the Internet was transforming genealogical research, making it possible to find ancestors in old records from all over the world, Alice was already decades deep into this hobby and had subscribed to Ancestry.com to access its vast trove of historical records. And this is why she found out as soon as the company started offering an at-home DNA test in 2012.

These days, Ancestry’s database is stocked with the genetic data of more than eighteen million customers, but back then, the kind of test the company was making available to subscribers—autosomal DNA testing—was relatively new and not widely known about. Alice’s scientific curiosity was piqued. If the paper trail could not help her, she thought perhaps the genetic trail could. The timing was fortuitous, as Alice thought she’d homed in on the village her father’s father had emigrated from, and was considering a trip to Ireland. She got on the company’s waiting list for the test.

There are two ways that home DNA testing companies collect your genetic material. One method is to have the customer swab the inside of her cheeks, and another is to have her spit in a vial. AncestryDNA uses saliva. When the company’s box arrived at Alice’s house, she opened up the vial and spit and spit, about ten times, until the bubbles of saliva cleared a line on the side of the tube. She closed the top, which released a preserving liquid into her saliva, put the vial in a package, and sent it back to the company. And then she waited.

* * *

Before autosomal DNA testing came on the scene, two types of genetic testing dominated the consumer market for those interested in tracing their ancestral histories. One, called Y-DNA testing, examines the Y chromosome a man inherits from his father’s father’s father . . . all the way up what’s known as the patrilineal line. Only men can take the test, since only men inherit a Y sex chromosome along with their X (women, of course, inherit two X’s). The other test looks at mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA). Whereas our twenty-three pairs of chromosomes sit inside the nucleus of the cell, the tiny mitochondrion sits outside the nucleus with its own DNA, and both men and women inherit mitochondrial DNA from their mother’s mother’s mother . . . all the way up the matrilineal line. Both of these kinds of testing can tell a person about one particular genetic line, but not about their maternal or paternal side as a whole, nor about the genetic heritage they inherited from their other parent.

Because mitochondrial DNA and Y-DNA are inherited more or less intact, geneticists use mutations, which happen slowly over time, to trace historical migrations and track branches on our huge family tree of humanity. Y-DNA and mtDNA testing can tell us where some of our ancient ancestors lived, but typically can’t give us precise information about our immediate family trees, nor can they offer predictions about a person’s overall ethnicity. Although they can reveal that you and another person share a common ancestor, it can be difficult to tell how closely related you are to that other person. However, there are instances where these kinds of DNA can be helpful for genealogical purposes. Because the Y chromosome passes from father to son relatively unchanged, for instance, it can be used in combination with a surname, which also typically passes from father to son, to trace the genealogy of a male line.

As it happens, some of Alice’s family had already begun dabbling in genetic testing. Her sister, Gerry, who was also interested in the Collins family’s history, had recently had her mitochondrial DNA tested, showing her deep ancestry along her matrilineal line, and Gerry and Alice had convinced one of their brothers to test his Y chromosome, in hopes of getting a sense of their father’s side. But the AncestryDNA test, when it became available, was a wholly different animal, offering much more recent and comprehensive genealogical information. AncestryDNA’s test looked at the twenty-two pairs of chromosomes that don’t determine a person’s genetic sex, known as autosomes. It considered the genetic material contributed by both parents and by their parents before them. It could reveal recent genetic ethnicity and show relatives along both the maternal and paternal sides, assuming they were in the company’s database. It promised, in other words, to help Alice unravel her father’s genealogical knots.

Alice waited over a month to get her results back. Finally, she got a notification they were ready. She logged on—and was utterly perplexed.

She was just 48 percent British Isles, AncestryDNA informed her. She should have been more like 100 percent, given her dad’s Irish ancestry and her mom’s Irish, English, and Scottish mix. Instead, the test results suggested that the other half of Alice’s ethnic makeup was a mix of what the company called “European Jewish,” “Persian/Turk...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Prologue

- 1. Alice Is Not Alice

- 2. Crude Beginnings

- 3. Somebody Ought to Start a Business

- 4. Your Truth or Mine?

- 5. Non-paternity Events

- 6. Alice and the Double Helix

- 7. Eureka in the Chromosomes

- 8. Search Angels

- 9. 27 Percent Asia Central

- 10. What to Claim

- 11. The Mystery of Jim Collins

- 12. The Simplest Explanation

- 13. The American Family

- 14. Your Genes Are Not Yours Alone

- 15. Late Night

- 16. Alice Redux

- 17. Where We’re Going

- Selected Bibliography

- Acknowledgments

- Index