A BRIEF LOOK AT STREET DESIGN STANDARDS OF ANTIQUITY

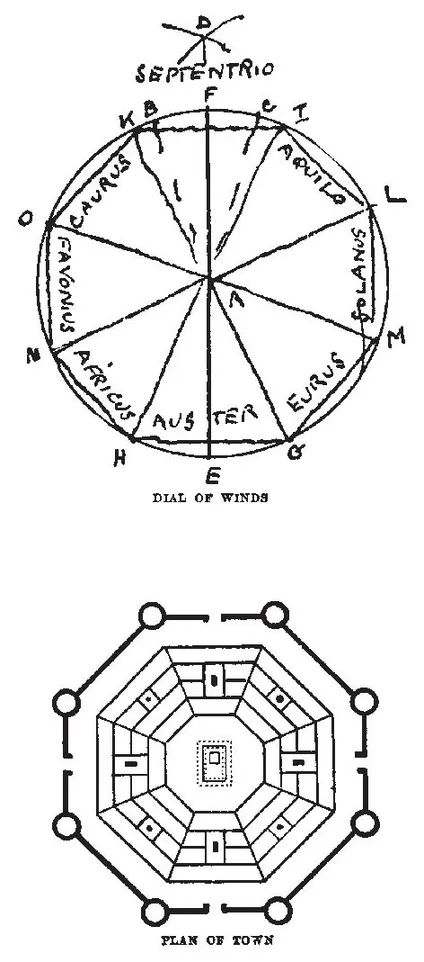

Today’s standards for street design have roots in ancient practice and road building technologies. Roman street standards and paving ordinances provided the foundation for modern road building technique and design. In Mediterranean towns streets were typically narrow and wheeled traffic was controlled, thus eliminating the need for wider streets. Moreover, the hot climate made the shady narrow streets more comfortable. In the first century B.C., the Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius advised that streets should be laid out to control winds, which would bring humidity and disease into the city: “When the walls are set round the city, there follow the divisions of the sites within the walls, and the layings out of the broad streets and the alleys with a view to aspect. These will be rightly laid out if the winds are carefully shut out from the alleys. For if the winds are cold they are unpleasant; if hot, they infect; if moist, they are injurious.... For when the quarters of the city are planned to meet the winds full, the rush of air and the frequent breezes from the open space of the sky will move with mightier power, confined as they are in the jaws of the alleys. Wherefore the directions of the streets are to avoid the quarters of the winds, so that when the winds come up against the corners of the blocks of buildings they may be broken, driven back and dissipated.”1 Vitruvius went on at length on the names and characteristics of the different winds and how to lay out the streets accordingly.

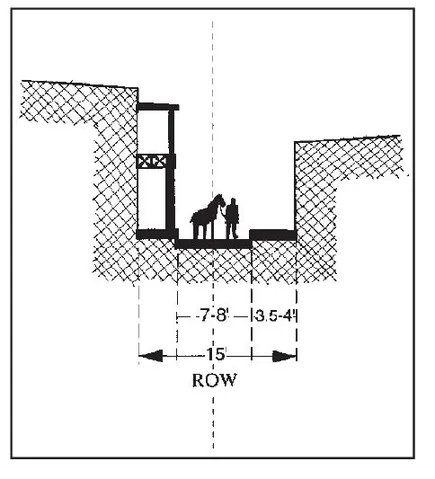

The earliest known written law regarding streets dates back to about 100 B.C., and fixed the width of Roman streets at a minimum of 15 feet (4.5 m).2 Previous street construction did not follow any regulations. In Pompeii until 200 B.C., the streets were paved at various widths while the houses facing them were low and small. When the peristyle or courtyard house came into fashion from 200 B.C. to 100 B.C., houses encroached into the street and formed narrower arcade streets similar to those of Hellenistic cities. Romans later adopted this style, which reached its peak in the Imperial period. The tendency to build higher houses created dark and narrow passages, insufficient for wheeled traffic. As a result, in 15 B.C. Augustus limited the height of buildings to 66 feet (20 m) and no more than six stories. He also made a new law fixing the main intersecting axes of the grid: the decumanus, the east–west processional road, was to be 40 feet (12.2 m); the cardo, the main north–south road, was set at 20 feet (6 m); and the vicinae, side roads, were to be 15 feet (4.5 m).

Streets were narrow and paved in ancient Mediterranean towns like Jerusalem. In the hot climate, narrow shady streets were more comfortable for pedestrians, and since wheeled traffic was regulated, there was no need for wide streets. (© Eran Ben-Joseph)

The Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius wrote on the layout of streets in the first century B.C. He conceived his octagonal ideal city to control the eight winds, which he analyzed in some detail in his treatise on architecture. (Frank Granger)

Streets of Rome were usually paved with basalt slabs. Elevated sidewalks paved with peperino stone were usually built on both sides of the street and took as much as half of the total street width. Roads outside the city were either paved or, at minimum, graveled. In 47 B.C. traffic congestion became such a problem citywide that Caesar forbade transport during the daytime except for materials for public buildings or for festivals and games. Wagon transport, including the removal of refuse and rubble to the dumps outside the towns, was restricted to nighttime.

The excavations at Herculaneum,

which was buried in lava when

Vesuvius erupted in 79 A.D., uncov-

ered a typical Roman city street

from the first century A.D. The

street is narrow and paved in stone,

with raised sidewalks on both sides.

Several houses encroach into the

street to form protective arcades at

the pedestrian level.

(© Alinari/ArtResource, N. Y.)

Emperor Augustus set standards for

street widths in 15 B.C. The width

of vicinae—side roads—was about

15 feet. (© Eran Ben-Joseph)

While the Roman city street, with its elevated sidewalks, became the prototype for modern street design, it was viae militares, military roads, that were the foundation for contemporary construction techniques. By the peak of the Roman Empire in 300 A.D., almost 53,000 miles of military roads had been built connecting Rome with the frontiers. The typical Roman road was constructed of four layers: flat stones, crushed stones, gravel, and coarse sand mixed with lime. Paving stones and a wearing surface of mortar and a flintlike lava were laid on top. Roads were usually about 35 feet (10.6 m) wide, with two central lanes 15.5 (4.7 m) feet wide for two directions of traffic, and were lined by freestanding curbstones 2 feet (0.6 m) wide and 18 inches (45 cm) tall. On the outer side of the curbs a one-way lane about 7.5 feet (2.3 m) wide was laid. This basic section and construction technique set the standard for road construction in Europe until the late eighteenth century.3

The Roman viae militares, or military roads, like the Appian Way connected Rome with the outer limits of the empire. These roads became the prototype for modern road construction. (©Donald Appleyard)

The typical Roman road consisted of layers of flat stones, crushed stones, gravel, and coarse sand mixed with lime. The top surface was smooth paving stones and mortar. Two central traffic lanes were bordered by curbs 2 feet wide and 18 inches tall. The outside lanes were for one-way traffic. This construction method was standard in Europe until the late eighteenth century. (Aitken)

After the collapse of the Roman Empire in 476 A.D., many Roman cities fell into a prolonged period of decline and decay. With the breakdown of administrative and political systems, controls over land eroded. Formerly public spaces such as streets were encroached upon. This erosion of the clear and regular Roman grid is seen in the evolution of the street patterns of Bologna, Verona, Naples, and many other cities built by the Romans. The superb paved Roman roadways deteriorated into an impassable ill-drained dirt road system, halting long distance vehicle travel. Carts and wagons were confined to farm and local use, while land travel was restricted to pedestrians or horses. Surviving cities struggled with repair and rebuilding of their defenses. Most cities were contained by enclosing walls and a few major streets led from the gateways to a focal center. Local internal streets were merely narrow passageways defined by the building walls and overhead arches. Streets were flagged with stones and often incorporated steps to facilitate pedestrian movement.

After the collapse of the Roman Empire, land controls weakened and the great Roman roads deteriorated. Encroachments into the public way were common. Streets became more irregular and often were little more than dark narrow passageways defined by tall building walls. (© Michael Southworth)

The clear and regular Roman gridiron found in cities like Bologna deteriorated in the Middle Ages, but fragments of the ancient grid pattern are still visible today. (© Michael Southworth)

With the steady growth of towns and cities during the ninth and tenth centuries, overcrowding and congestion became a serious problem. Confined by existing defensive walls, buildings grew higher, and without public controls over construction and land use, individuals encroached on the street space. The lack of sanitary conveniences and regulations, along with deteriorating pavement, added to the hazardous and unhealthy conditions. Streets were filthy. As late as 1372, Parisians were permitted to throw waste from their windows whenever they chose after giving a warning by shouting three times.

By the eleventh century Europe entered an era of expanding population, travel, and trade. Although land routes remained largely neglected, sea navigation ...