- 448 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

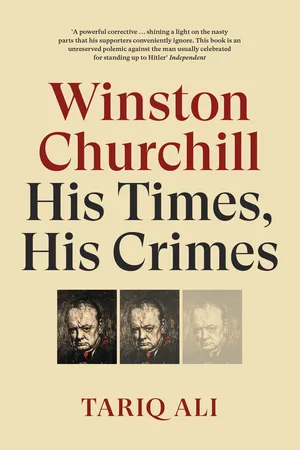

The subject of numerous biographies and history books, Winston Churchill has been repeatedly voted as one of the greatest of Englishmen. Even today, Boris Johnson in his failing attempts to be magisterial, has adopted many of his hero's mannerism! And, as Tariq Ali agrees, Churchill was undoubtedly right in 1940-41 to refuse to capitulate to fascism. However, he was also one of the staunchest defenders of empire and of Britain's imperial doctrine.

In this coruscating biography, Tariq Ali challenges Churchill's vaulted record. Throughout his long career as journalist, adventurer, MP, military leader, statesman, and historian, nationalist self belief influenced Churchill's every step, with catastrophic effects. As a young man he rode into battle in South Africa, Sudan and India in order to maintain the Imperial order. As a minister during the first World War, he was responsible for a series of calamitous errors that cost thousands of lives. His attempt to crush the Irish nationalists left scars that have not yet healed. Despite his record as a defender of his homeland during the Second World War, he was willing to sacrifice more distant domains. Singapore fell due to his hubris. Over 3 Millions Bengalis starved in 1943 as a consequence of his policies. As a peace time leader, even as the Empire was starting to crumble, Churchill never questioned his imperial philosophy as he became one of the architects of the postwar world we live in today.

In this coruscating biography, Tariq Ali challenges Churchill's vaulted record. Throughout his long career as journalist, adventurer, MP, military leader, statesman, and historian, nationalist self belief influenced Churchill's every step, with catastrophic effects. As a young man he rode into battle in South Africa, Sudan and India in order to maintain the Imperial order. As a minister during the first World War, he was responsible for a series of calamitous errors that cost thousands of lives. His attempt to crush the Irish nationalists left scars that have not yet healed. Despite his record as a defender of his homeland during the Second World War, he was willing to sacrifice more distant domains. Singapore fell due to his hubris. Over 3 Millions Bengalis starved in 1943 as a consequence of his policies. As a peace time leader, even as the Empire was starting to crumble, Churchill never questioned his imperial philosophy as he became one of the architects of the postwar world we live in today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Winston Churchill by Tariq Ali in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

A World of Empires

Now, this is the faith that the White Men hold

When they build their homes afar –

‘Freedom for ourselves and freedom for our sons

And failing freedom, War.’

Kipling, ‘A Song of the White Men’ (1899)

‘I was a child of the Victorian era,’ wrote Churchill in My Early Life, ‘when the structure of our country seemed firmly set, when its position in trade and on our seas was unrivalled, and when the realisation of the greatness of our Empire and of our duty to preserve it was ever growing stronger.’ In 1874, when Churchill was born, Britain was the dominant empire, its global reach surpassing that of its rivals. It had lost its American colonies but retained a boot-hold in Canada. The American losses were more than recompensed by the conquest of India. Africa was divided according to an agreement reached by the European powers.

Most Europeans of all classes viewed their respective colonies in a similar fashion. None could match, whatever else may be thought of it, the Iberian seizure and possession for three centuries of a vast continent beyond a perilous ocean. That was a feat unparalleled in history. Yet even today the majority of Churchill’s biographers cling to the view that while the Spanish Empire and others were cruel, indeed barbarous, the British Empire was more benign and, for this reason, more appreciated by those it colonised.

As a result, the British Empire has become a staple of the heritage industry. The Thatcher governments of the 1980s (and their Blairite successors) did not simply assault the hallowed domains of the welfare state or destroy trade union militancy, they also sought to reverse anti-colonial trends in the public sphere that rubbished or were sharply critical of Britain’s imperial past. The response to this shift has come from many sources. In Britain, most recently, the cosmetic version of colonisation has been effectively demolished by the English historian Richard Gott in his masterly study of resistance to the British Empire. He encapsulates the problem neatly:

[I]t is often suggested that the British Empire was something of a model experience, unlike that of the French, the Dutch, the Germans, the Spaniards, the Portuguese – or, of course, the Americans. There is a widespread opinion that the British Empire was obtained and maintained with a minimum degree of force and with maximum co-operation from a grateful indigenous population. This benign, biscuit-tin view of the past is not an understanding of their history that young people in the territories that once made up the Empire would now recognize.1

It is through this lens that we need to see the young imperialist, Winston Churchill. A particular kind of Victorian-era child, he spent his early formative years in a colonial setting, living in Dublin where his grandfather was viceroy of Ireland. As a boy neglected by his parents, he found solace in toy soldiers and oft-repeated tales of his great military forebear, the first Duke of Marlborough. Stories of the duke’s tactical prowess on international battlefields – not to mention his political cunning, beginning with the Glorious Revolution – only enhanced the young Churchill’s desire to be a soldier.

The parental neglect continued when he was sent away to school at Harrow. There he found comfort in the school cadet corps and began to prepare himself for the military academy at Sandhurst, where competition for a place was stiff. His father, Lord Randolph Churchill, by then a Tory MP, was not keen on the idea, preferring that his son might join a financial firm in the City (Rothschild was a friend) and make some money. Winston, both scared and in awe of his striving, reckless and bad-tempered father, persisted nonetheless, and after two failed attempts finally got into Sandhurst.

His marks being insufficient to join the infantry (which in those days prized intellect highly), Churchill was, like many other upper-class men, assigned to the more glamorous but less demanding cavalry. That same year, 1893, to celebrate his elevation to cadet, he went on a skiing holiday in Switzerland. His enjoyment was cut short by a stern missive from his father, a man whose mental stability was impaired by syphilis and who had hitherto given no personal attention to his son:

Never have I received a really good report of your conduct in your work from any master or tutor you had from time to time to do with. Always behind-hand, never advancing in your class, incessant complaints of total want of application … [W]ith all the efforts that have been made to make your life easy and agreeable and your work neither oppressive nor distasteful, this is the grand result that you come up among the 2nd rate and 3rd rate class who are only good for commissions in a cavalry regiment … I shall not write again on these matters and you need not trouble to write any answer to this part of my letter because I no longer attach the slightest weight to anything you may say about your own acquirements and exploits. Make this position indelibly impressed on your mind, that if your conduct and action at Sandhurst is similar to what it has been in the other establishments in which it has sought vainly to impart to you some education. Then that my responsibility for you is over.’

It is not difficult to imagine the psychological impact such a letter might have had on a nineteen-year-old boy (though it should be pointed out that language of this sort deployed by an upper-class father to his son was not unfamiliar at the time or later). On a psychological level, from this moment on, proving his father wrong became part of Winston’s life work.

His American heiress mother, Jennie Jerome, was only marginally better as a parent. She was fond of Winston in absentia. As he grew up, she was not averse to sleeping with the highest figures in the realm to help his career and re-fill her own purse, emptied after an economic collapse in the United States wrecked her family’s fortune. She did the rounds of the SW1 squares (even, according to some reports, sleeping with the king), a process that had begun while her husband was dying of syphilis and continued apace after his death.

There was a possibility at one stage that Churchill might succeed to the dukedom, since his cousin Sunny, in direct line, was unmarried. The duchess insisted that ‘it would be intolerable if that little upstart Winston ever became duke’, and summoned the monied cavalry in the US to mount a rescue. Eventually, Consuelo Vanderbilt was persuaded to marry the wastrel Sunny. Accompanying the heiress was a lump sum donation of $2.5 million and an annuity of $30,000, a useful contribution to the family coffers. In due course, a child was produced. No chance now of Churchill moving to Blenheim. Winston would have to make his own fortune.

Could the young cadet at Sandhurst graduate to the status of an imperial warlord? No doubt he would have loved that, but it was not to be. A few adventures observing and participating in wars was all fate assigned to him. But he never had any doubts regarding the efficacy of imperial rule. Proud of his glorious ancestor, founder of the Marlborough/Churchill dynasty, he was determined to play his part in defending the Empire in both theory and practice. War was an elixir, a cure-all for boredom and ennui, and more exciting than hunting since the targets were usually ‘savages’. Whatever language they spoke, however ‘primitive’ they might be, they were human rivals. What other adventure could beat this one? War was, in Churchill’s own words, a most ‘desirable commodity’.

At twenty-one, however, newly enlisted with the 4th Hussars, Winston was to be disappointed. It was 1895 and there was no British colonial war in sight. He was bored at home and ‘all [his] money had been spent on polo ponies’. How then to find the ‘swift road to distinction’ and the ‘glittering gateway’ to fame? After a few inquiries, his gaze crossed the Atlantic. As he later recalled, since

[I] could not afford to hunt, I searched the world for some scene of adventure or excitement. The general peace in which mankind had for so many years languished was broken only in one quarter of the globe. The long-drawn guerrilla war between the Spaniards and the Cuban rebels was said to be entering upon its most serious phase.2

The Spanish Empire was in a state of collapse. It had been attempting to suppress two liberation movements simultaneously for years, in Cuba and the Philippines. The political-intellectual leadership of these movements was provided by José Martí in Cuba and José Rizal in the Philippines: the first a poet and essayist, the second a novelist of the highest rank. Both lives were tragically truncated, Martí in a military skirmish, Rizal executed by a Spanish firing squad.

Cuba and Puerto Rico were the last remaining Spanish possessions in the Americas and among the least developed colonies. The discovery of gold and silver on the mainland and the relative lack of either men or minerals to exploit in Cuba relegated the island to a minor, mainly military and administrative, role in the imperial system. Between 1720 and 1762, the Cuban economy was so undeveloped that its entire European trade was carried by an average of only five or six merchant ships each year. The plantation system, dependent on the large-scale slavery of kidnapped Africans, began late, and only escalated after the Haitian Revolution. The drive for independence was delayed too. By 1825, the whole of the Spanish American mainland had been liberated, but in Cuba Spanish rule lasted until 1898. In 1895, as Churchill weighed his options, Spain was waging a vicious last-ditch assault against the Cuban patriots.

Churchill was never slow to exploit an opportunity, and this one was perfect. He obtained leave from his regiment to become a military observer and witness a colonial war first-hand. Having been left a skimpy inheritance by his father, who had died at the start of that year, he struck on journalism as a means both to promote himself and earn some money. He sought and obtained a newspaper commission to cover the Spanish–Cuban war. Together with a fellow officer, he set off for the Caribbean via the United States.

Churchill did not need to know too much about his chosen war zone. Instinctively, he sided with the Spanish. The reason was simple: an imperial power was attempting to drown a native rebellion in blood.

He arrived in Havana in November 1895. Typhus, smallpox and cholera stalked the island. Famine was widespread, and any journalist who travelled a bit could not have failed to witness the immense suffering of the Cubans. Nevertheless, Churchill underplayed these horrors, themselves a direct result of the colonial war. In an early despatch home – getting almost everything wrong, not unlike journalists reporting from five-star hotels in more recent colonial wars – he wrote:

[Havana] shows no sign of the insurrection, and business proceeds everywhere as usual. Passports are, however, strictly examined, and all baggage is searched with a view to discovering pistols or other arms. During the passage from Tampa on the boat the most violent reports of the condition of Havana were rife. Yellow fever was said to be prevalent, and the garrison was reported to have over 400 cases. As a matter of fact, there is really not much sickness, and what there is is confined to the lower part of the town.3

Even when Churchill could no longer ignore what was taking place, and realised that the Cuban Revolutionary Party had the overwhelming support of the people, he could not bring himself to examine let alone appreciate the perspective of its fighters. The Spanish he understood only too well. For them, Cuba was what Ireland was for the British.

José Martí does not rate a single mention in Churchill’s reports or in My Early Life. Martí had written to the British foreign secretary in April 1895, pleading that Britain stay out of the conflict. Three weeks later, he was dead, shot by the Spanish in an unnecessary encounter. The result was an avoidable tragedy. These events, involving Cuba’s most prominent nationalist leader, were still fresh when Churchill arrived, but he could think only of how much luckier Cuba might have been had the British not exchanged Havana for Florida in 1763 after an eleven-month occupation:

It may be that as the pages of history are turned brighter fortunes and better times will come to Cuba. It may be that future years will see the island as it would be now, had England never lost it – a Cuba free and prosperous, under just laws and a patriotic administration, throwing open her ports to the commerce of the world, sending her ponies to Hurlingham and her Cricketers to Lords, exchanging the cigars of Havana for the cottons of Lancashire, and the sugars of Matanzas for the cutlery of Sheffield.

Churchill was only too aware of what imperialism entailed. Could he have been unaware that it was during the brief period of British occupation in 1762 that 10,000 more slaves had been imported into Cuba to sustain a thriving plantation economy?4

In December 1954, about to enter his final decade, Churchill listened to tales of woe told by a visiting white settler from Kenya, who explained why the atrocities against the Mau Mau rebellion were necessary. Churchill was worried mainly by how these might affect Britain’s standing in the world. He recalled his own 1907 trip to the African colony, when the Kikuyu tribe was such ‘a happy, naked and charming people’. But now, he wrote, public opinion would watch ‘the power of a modern nation being used to kill savages. It’s pretty terrible. Savages, savages? Not savages. They’re savages armed with ideas, much more difficult to deal with.’5

There were plenty of ‘savages’ in Cuba too. In 1895 and 1896, as the rebels gained more support, Generals Antonio Maceo and Máximo Gómez had the island virtually under their control and Havana under siege. Maceo, an Afro-Cuban, was without doubt the most outstanding guerrilla leader of the nineteenth century. Spain and its supporters went into panic mode. Churchill described the rebels as ‘an undisciplined rabble’ consisting ‘to a large extent of coloured men’. If the revolution succeeded, he worried, ‘Cuba will be a black republic’, registering no connection to the slaves Britain had brought in to increase the enslaved population Spain had already accumulated over the previous two centuries.6

Self-induced amnesia has always been a characteristic of imperial leaders and their ideologues. Fears of another Haiti in the region were ever present in the thinking of the United States as well. Grover Flint, a US journalist who had attached himself to Gómez’s army, wrote in his despatches that ‘half of the enlisted men were negroes’ while other sinister types were also present: ‘Chinamen (survivors of the Macau coolie traffic) … shifty, sharp-eyed Mongols, with none of the placid laundry look about them’.7

The Spanish had agreed to the abolition of slavery in Cuba in 1886, but, fearful of the very notion of a majoritarian black republic, they encouraged mass migration from the peninsula to the island. Between 1882 and 1894 a quarter of a million Spaniards emigrated to Cuba, whose population was then under two million. They included the Catalan anarchist Enrique Roig, who wasted little time in linking up with Martí. The flood of white immigrants did not prove sufficient from the Spanish point of view. Two-thirds of the ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Chronology

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: The Cult of Churchill

- 1. A World of Empires

- 2. Skirmishes on the Home Front

- 3. The ‘Great’ War

- 4. The Irish Dimension

- 5. The Wind That Shook the World

- 6. Nine Days in May, 1926

- 7. The Rise of Fascism

- 8. Japan’s Bid for Mastery in Asia

- 9. The War in Europe: From Munich to Stalingrad

- 10. The Indian Cauldron

- 11. Resistance and Repression

- 12. The Origins of the Cold War: Yugoslavia, Greece, Spain

- 13. The East Is Dead, the East Is Red: Japan, China, Korea, Vietnam

- 14. Castles in the Sand: Re-mapping the Arab East

- 15. War Crimes in Kenya

- 16. What’s Past Is Prologue: Churchill’s Legacies

- Notes

- Epilogue

- Select Bibliography

- Index