- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

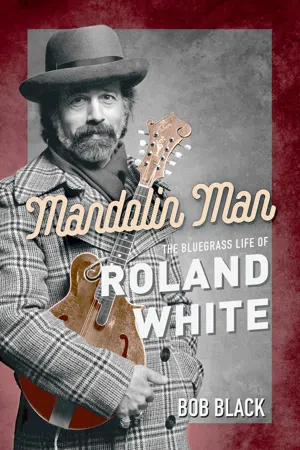

A No Depression Most Memorable Music Book of 2022

Roland White's long career has taken him from membership in Bill Monroe's Blue Grass Boys and Lester Flatt's Nashville Grass to success with his own Roland White Band. A master of the mandolin and acclaimed multi-instrumentalist, White has mentored a host of bluegrass musicians and inspired countless others.

Bob Black draws on extensive interviews with White and his peers and friends to provide the first in-depth biography of the pioneering bluegrass figure. Born into a musical family, White found early success with the Kentucky Colonels during the 1960s folk revival. The many stops and collaborations that marked White's subsequent musical journey trace the history of modern bluegrass. But Black also delves into the seldom-told tale of White's life as a working musician, one who endured professional and music industry ups-and-downs to become a legendary artist and beloved teacher.

Roland White's long career has taken him from membership in Bill Monroe's Blue Grass Boys and Lester Flatt's Nashville Grass to success with his own Roland White Band. A master of the mandolin and acclaimed multi-instrumentalist, White has mentored a host of bluegrass musicians and inspired countless others.

Bob Black draws on extensive interviews with White and his peers and friends to provide the first in-depth biography of the pioneering bluegrass figure. Born into a musical family, White found early success with the Kentucky Colonels during the 1960s folk revival. The many stops and collaborations that marked White's subsequent musical journey trace the history of modern bluegrass. But Black also delves into the seldom-told tale of White's life as a working musician, one who endured professional and music industry ups-and-downs to become a legendary artist and beloved teacher.

An entertaining merger of memories and music history, Mandolin Man tells the overdue story of a bluegrass icon and his times.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mandolin Man by Bob Black in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medien & darstellende Kunst & Musikbiographien. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Doing It for Real

I’ve always thought of Roland White as a pro who was just as much a part of the world of bluegrass as any of the other major pioneers. His name wasn’t out front much, however. He was a trench fighter, a lower-ranking soldier bearing the burdens without getting much recognition. He lived to play the music. It was his passion. Recognition didn’t matter; his ego could handle that. What mattered most to Roland was “doing it for real”—that’s his description of the rare musicians who actually try to make a living with music. It wasn’t just a hobby, or something to be talked about, or become an expert on.

It seems like I’ve known Roland White all my life. We share the same musical interests and background. I was first drawn to bluegrass while listening to Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs and the Foggy Mountain Boys. I was trying to copy Earl’s banjo licks. I grew up admiring that band and buying their records. I listened to their early morning Martha White show whenever my old-fashioned radio could pick it up; AM 650 in Nashville was a long way from Des Moines. Shortly after Earl left Lester in 1969, Roland White joined the group, which was renamed the Nashville Grass. All the same members remained in the band except Earl, who was replaced by Vic Jordan. In effect, Roland was actually playing with the Foggy Mountain Boys minus Earl, and that put him on a pedestal in my mind. I continued to buy Lester’s records when Roland White was with him. His name became part of my bluegrass vocabulary.

Later I found out that Roland had also played for the “Father of Bluegrass,” Bill Monroe, and in my eyes that elevated his stature even more. After a little research, I learned he had been a founding member of the Kentucky Colonels, a legendary bluegrass band that existed from 1962 to 1966, but I couldn’t find any of their records in the Des Moines area, so that band remained mythological to me.

Marty Stuart, a member of the Country Music Hall of Fame in Nashville, is deeply rooted in bluegrass. He has taken it upon himself to be a historian and ambassador of genuine bluegrass and country music, and he shares a personal musical background with Roland White. I interviewed Marty in Winterset, Iowa, in May 2016 at the grand opening of the John Wayne Birthplace and Museum. In speaking about Roland White, Marty took an unusual conversational approach. Here’s part of what he said:

We toured out in California two or three years ago, and it was very successful, and when I got home, I picked up the phone and called Merle Haggard [1937–2016]. I said, “I just want to thank you and the Strangers and Buck and the Buckaroos and all you guys for what you did to set up a trail for us, because those people still love it.” Merle said to me, “Hey, we all owe the debt to the Maddox Brothers and Rose because they were the first ones to bring the sound out here.”1

Haggard was right. The Maddoxes had brought their hot, honky-tonk music from Alabama to the West Coast in 1933, when Rose was only seven. Nearly penniless, they hitchhiked and rode in boxcars, staying in migrant communities, and eventually wound up in Modesto, California. They performed at dances, fairs, rodeos, bars, and on radio programs.2 Later they became known as “America’s Most Colorful Hillbilly Band.”3

The Maddox influence lives on in the “Bakersfield sound,” which started in the honky-tonks around Bakersfield, California. It was a reaction to the overproduced music coming out of Nashville, and the sound was popularized by Buck Owens, Merle Haggard, Tommy Collins, Wynn Stewart, Jean Shepard, and many others.4 Modern-day artists influenced by the Bakersfield sound include Dwight Yoakam and Marty Stuart. Even the Beatles were influenced by the Bakersfield sound when in 1965 they recorded “Act Naturally,” originally a Buck Owens hit.

Marty then came to his point by comparing Roland White and his musical family to the Maddox Brothers and Rose, who sowed the seeds of the Bakersfield sound: “The same can be said for the Kentucky Colonels. If you go back to bluegrass in California, they were among the very first people there. They played in bowling alleys and anywhere they could get a job. Roland White and his brothers, Eric and Clarence, lit the fuse and opened the door for everything that has happened since.”5

Vic Jordan—who had played with all the greats, including Wilma Lee and Stoney Cooper, Jimmy Martin, Bill Monroe, Lester Flatt, Jim and Jesse, and many others—agreed with Roland on the subject of doing it for real. In our conversation of March 2015, this is what he told me:

What I call a professional musician is not how good you are but whether you make your living at it. That doesn’t mean guys who play excellent but don’t make their living aren’t professional grade—they certainly are—but that’s how I distinguish professional from nonprofessional. People used to ask us all the time, “What do you guys do for a living for the rest of the week?” I said, “I don’t do anything [except music] for the rest of the week.”“Well, you can’t make your living playing music, can you?”“You see me here, don’t you? You know how many years it took to get here?”6

I joined Bill Monroe’s Blue Grass Boys in 1974. I’m so glad I took the opportunity to do that when the chance came along. Moving to Nashville taught me a lot. There are musicians there who have come from all over the country, and most know all about the disappointment involved and the perseverance required in doing it for real. That’s why they all admire Roland White. He’s never given up on his dreams, and he’s made countless life adjustments in order to fulfill those dreams. You can’t just take what life gives you and sit back and complain about the unfairness of it all. You have to turn things around yourself and step it up and go. That’s what Roland has always done.

When I first entered the Nashville bluegrass music scene, Roland had only recently lost his brother Clarence, who was an original member of the Kentucky Colonels and later became lead guitarist for the Byrds. I wasn’t even aware of Clarence’s passing. Roland was always at the Station Inn,7 Nashville’s longtime bluegrass music gathering place, singing and playing as though nothing was even wrong or missing. The tragedy of losing his brother had put an end to the New Kentucky Colonels, an exciting and promising rebirth of their earlier band.

Nothing ever seemed to stop Roland. He was coming from a totally different perspective than I was. I’d arrived in town with a job already in hand, and I figured I’d just keep that job forever, not knowing about the dangers lurking ahead. When I lost the job with Monroe, I stayed around town for a couple of more years, but my attitude never really bounced back like it should have. I should have stayed around like Roland did. The importance of mental toughness was the greatest life lesson I learned from having lived in Nashville. I never regretted my four and a half years in Music City, but I also had good reasons for moving back to Iowa. I felt more at home among Midwesterners. Kristie, the girl I married in 1990, is a fellow Iowan, and we share many of the same common, down-to-earth values that make our state so wonderful.

By contrast, Roland White spent the first part of his childhood in rural Maine and the second part in teeming Los Angeles. Growing up at both ends of that spectrum resulted in a worldview characterized by enthusiastic receptiveness to change. Being the oldest in a musical group of siblings brought responsibility to him, and he was energized by a restless desire to succeed. Early exposure to some of the greatest country music stars in the LA area was the flame that ignited Roland’s dream of making a career out of performing on stage. Eventually that dream led him to Nashville.

Playing music is something many people can do well, but that’s only a small part of doing it for real. Perseverance is the key, and Nashville requires a level of perseverance that is way beyond what most people have. Roland has been there for many years, in the thick of it, steady and enduring. He’s been an inspiration to many musicians, past and present, and he’s passing along an unmatched tradition to the incredible talent coming up.

The name Roland White stands on its own. Though he’s been a part of several of the most influential bands in the history of bluegrass, his legacy isn’t tied exclusively to any one of them. Many exceptional singers and musicians make a name for themselves while performing with one certain group, and when that group runs its course—however successful it may be—those performers are remembered only as a part of that one particular band. It’s kind of like an actor becoming stereotyped in one role or character; truly great actors don’t allow themselves to fall into that trap. And so it is with top-notch musicians like Roland White: his career has spanned the entire panorama of bluegrass, and he has achieved enviable success in every setting.

The story of Roland White is a fascinating one, with an uplifting central theme. He made a childhood commitment to playing bluegrass music for a living—something that is very nearly impossible to do—and he has stuck by that commitment all through the years. It hasn’t always been easy, but his love of the music has carried him through in a very inspiring way. He doesn’t give up on his dreams.

Roland is a man who has done so many things, played with so many people in so many places and influenced so many lives, that to document and chronologically arrange all of these elements is a great challenge. However, through it all runs a constant thread: everyone who has ever come into contact with Roland loves him as a person as well as a musician. I first got to know him in the 1970s, playing and jamming with him a handful of times, attending many of his concerts, and feeling a sense of kinship with him that countless other musicians have also felt. We all love him. “Who wouldn’t?” says Alan Munde, a banjo player who has performed, traveled, and recorded with Roland for many years.

For over six decades Roland has been blazing trails, making elemental contributions to the evolution of a musical style that is unique and unforgettable. Unlike most other genres of music, bluegrass has not yet become totally homogenized (intermingled with other styles of music to create a hybrid sound that offends no one but is bland and unexciting as a result). It’s a special kind of music, to be cherished and treasured like a gem handed down from one’s ancestors. Roland’s contributions to bluegrass are some of the most notable to be found. Indeed, he’s an enduring part of the foundation; his style, technique, approach, and attitude are fundamental elements of bluegrass today. His improvisational and creative touches are always present while remaining within the framework designed by the music’s acknowledged creator, Bill Monroe.

Roland is gracious, humble, and genuine—full of twenty-four-carat qualities that no faker could possess. Easygoing, composed, and self-assured, he displays his gifts and shares himself without reserve. He lives with memories of triumphs and tragedies that define who he is. He’s a product of nearly seventy years of traveling, performing, and relating with loyal listeners who share his artistic passion. A musical master, he has crafted a style that is warm, unique, and intensely personal. He has performed and recorded with many of the most celebrated and renowned bluegrass groups to ever grace the genre: the Country Boys (1953–1961), the Kentucky Colonels (1963–1966), Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys (1967–1969), Lester Flatt and the Nashville Grass (1969–1973), the New Kentucky Colonels (1973), Country Gazette (1973–1987), the Nashville Bluegrass Band (1989–2000), and the Roland White Band (2000-present).

There are countless mandolin players who can play swarms of notes guaranteed to blow the listener away. It’s sometimes said of these types of musicians: “I wish I could do that, and then not do it.” But Roland is different. He’s been around long enough to differentiate between musical bluster and the real thing. He’s grown up with an instrument in his hands. It’s a part of him. He’s not out to prove anything; he’s just doing what he’s always done.

Silence is often more profound than words, just as the silence between notes is an important element of music. Listen to Roland’s playing—and what he doesn’t say. He’s not telling you, “Listen to me; you won’t understand what I’m doing, but you’ll marvel at my technical ability.” Instead, he shares his music with you, including you in the process. He doesn’t make you feel stupid. Truly great music is collaboration between artist and listener. No one understands that better than Roland.

Mike Compton, one of the foremost mandolin players around, had this to say about Roland’s playing:

I remember sitting with him in the Station Inn one night and watching a band play; I think it might have been the Johnson Mountain Boys. We were talking about playing music, and he said something about the space between the notes—they don’t feel like they have to be playing all the time. He’s the first person that I ever heard say anything much about the space being as important as the notes. At that point in time all I was thinking about was how to play the notes. He asked me if I had ever listened to any jazz players, and I told him, “Not that many.” He said sometimes whenever they stop playing, they won’t come back for about twelve or fourteen bars before they start playing again. When they come back, it really sounds like something.8

Diane Bouska, Roland’s wife and singing partner, has described his mandolin playing as much like watching a dancer performing different movements. This is a very apt description. His playing ornaments the melodies with graceful movements and flourishes and serves to remind us that all of the arts—visual, musical, and literary—are connected by a creative flow that comes from virtually the same wellspring. Roland sees his playing as like climbing a tree. “The melody is like the tree trunk,” he told me. “I’ll start down here at the bottom, then go out on a limb a little bit, fall off, and then I’ll climb back up and test another limb.”

Roland’s singing is also something that I’ve always had enormous respect for. His singing voice isn’t high, and it isn’t low—it’s mid-range. Roland can sing high harmony if he wants to, or if the group he is performing with needs a high harmony part, but he stays mostly in the middle of the vocal realm. He has the range of voice that a majority of singers can identify with. His study of classic bluegrass vocals is evidenced by his many recordings featuring songs by the masters he has performed with, such as Bill Monroe and Lester Flatt.

Roland has been a mainstay in the Nashville bluegrass scene for over fifty years. He moved there in 1967. He often performs at the Station Inn, which first opened in 1974 and is now known the world over as the place to go in Nashville to hear bluegrass. Top bluegrass names, as well as new and promising groups, often perform there. Roland White has been a supporter of the establishment from day one. He can be found quite often at jam sessions around town—places like the Fiddle House (fiddler Brian Christianson’s violin repair, sales, and rental shop) and the Authentic Coffee Company in White House, just outside of Nashville, where old-timers as well as young folks gather to jam and have a good time on Thursdays and Fridays. Jam sessions take place every Sunday evening at the Station Inn, and at the time we were visiting, Roland himself was organizing jam...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1 Doing It for Real

- 2 Birth of a Dream

- 3 The Country Boys

- 4 The Original Kentucky Colonels

- 5 The Blue Grass Boys

- 6 The Nashville Grass

- 7 The New Kentucky Colonels

- 8 Country Gazette

- 9 The Nashville Bluegrass Band

- 10 The Roland White Band

- 11 Roland’s Family Ties

- 12 A Visit with Roland and Diane

- 13 Back to Where It All Started

- Afterword

- Appendix A: People, Bands, and Venues

- Appendix B: Roland White’s Family

- Appendix C: Roland White Instructional Materials

- Notes

- Roland White Recordings Cited

- Index