eBook - ePub

Red Star Over Malaya

Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation, 1941-1946

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Red Star Over Malaya

Resistance and Social Conflict During and After the Japanese Occupation, 1941-1946

About this book

Red Star Over Malaya is an account of the inter-racial relations between Malays and Chinese during the final stages of the Japanese occupation. In 1947, none of the three major race of Malaya - Malays, Chinese, and Indians - regarded themselves as pan-ethnic "Malayans" with common duties and problems. With the occupation forcibly cut them off from China, Chinese residents began to look inwards towards Malaya and stake political claims, leading inevitably to a political contest with the Malays. As the country advanced towards nationhood and self-government, there was tension between traditional loyalties to the Malay rulers and the states, or to ancestral homelands elsewhere, and the need to cultivate an enduring loyalty to Malaya on the part of those who would make their home there in future.

As Japanese forces withdrew from the countryside, the Chinese guerrillas of the communist-led resistance movement, the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), emerged from the jungle and took control of some 70 per cent of the country's smaller towns and villages, seriously alarming the Malay population. When the British Military Administration sought to regain control of these liberated areas, the ensuing conflict set the tone for future political conflicts and marked a crucial stage in the history of Malaya. Based on extensive archival research, Red Star Over Malaya provides a riveting account of the way the Japanese occupation reshaped colonial Malaya, and of the tension-filled months that followed Japan's surrender. This book is fundamental to an understanding of social and political developments in Malaysia during the second half of the 20th century.

As Japanese forces withdrew from the countryside, the Chinese guerrillas of the communist-led resistance movement, the Malayan People's Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA), emerged from the jungle and took control of some 70 per cent of the country's smaller towns and villages, seriously alarming the Malay population. When the British Military Administration sought to regain control of these liberated areas, the ensuing conflict set the tone for future political conflicts and marked a crucial stage in the history of Malaya. Based on extensive archival research, Red Star Over Malaya provides a riveting account of the way the Japanese occupation reshaped colonial Malaya, and of the tension-filled months that followed Japan's surrender. This book is fundamental to an understanding of social and political developments in Malaysia during the second half of the 20th century.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Red Star Over Malaya by Boon Kheng Cheah in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Histoire & Histoire de l'Asie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

The Roots of Conflict

CHAPTER 1

Malaya’s Plural Society in 1941

At present only in name is this a Malay country. The Malays are outnumbered by the Chinese who swarm in by the thousands every year and monopolise all the jobs, wealth and businesses of this country.

– Za’ba, Al-Ikhwan, 16 December 1926

In 1941 “Malaya” was a convenient British administrative and geographical term comprising three political units: (1) the Straits Settlements colony of Singapore, Malacca, and Penang; (2) the Federated Malay States (FMS) of Selangor, Perak, Pahang, and Negri Sembilan; and (3) the Unfederated Malay States (UMS) of Perlis, Kedah, Kelantan, and Terengganu.

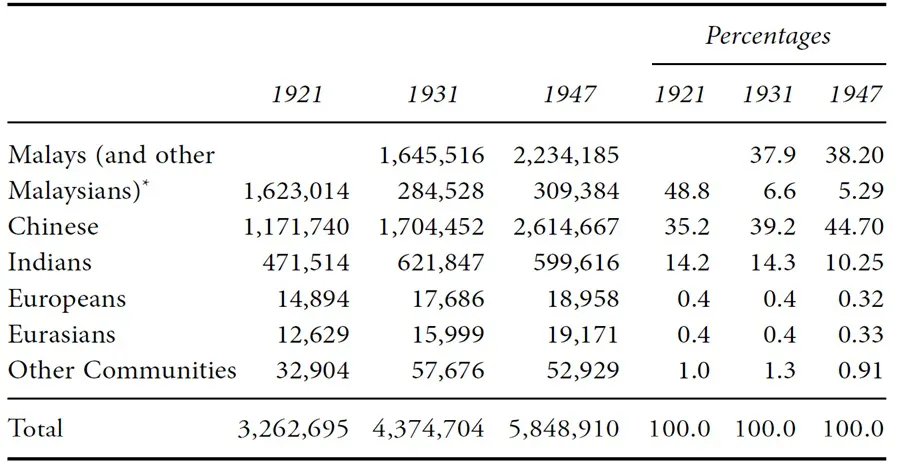

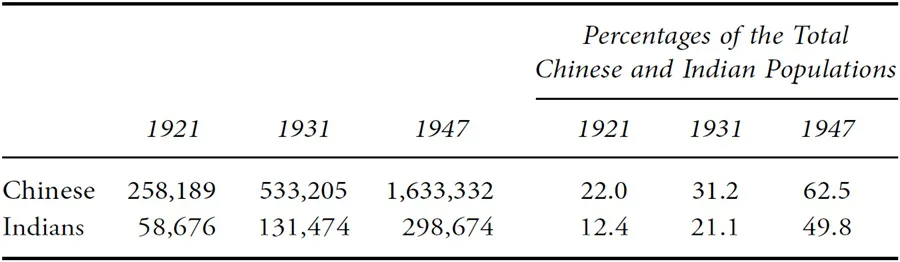

Nineteenth-century British colonial policy had transformed Malaya from a collection of Malay states into a “plural” multicom-munal society. Unrestricted immigration of Chinese and Indian labour (largely non-Muslim) for the tin mines and rubber estates had continued until 1921, but by then migrants already outnumbered the indigenous Muslim Malays. The 1921 census report showed that peninsular Malays and others of Malay-Indonesian stock numbered 1,623,014 (48.8 per cent of the total population), Chinese 1,171,740 (35.2 per cent), and Indians 471,514 (14.2 per cent). The British authorities generally regarded the Chinese and Indian immigrants as transients who for the most part, had little intention of making their permanent home in Malaya. Despite British colonial impressions to the contrary, the 1931 census report indicated about one-third of the Chinese and one-fourth of the Indians were local born and already showing a trend towards permanent settlement in the colony (see Table 1).

The Socio-Economic Setting

The preponderance of the Chinese and Indian communities in the economic life of the FMS was vividly illustrated by the fact that, according to the official estimates of 1934, Malays numbered only 643,003 out of a total FMS population of 1,777,421, Chinese came to 717,614, and Indians to 387,917. Of the four states in the FMS, Malays predominated only in underdeveloped Pahang where the total population of 186,465 contained 117,265 Malays. In the 1931 census, it had been established that in both the Straits Settlements and the FMS, the urban population was predominantly Chinese. The same was true of Johor (UMS). Even in Kedah (UMS) the largest single component of the urban population consisted of Chinese, though they just failed to equal in numbers the people of all other races combined. However, the towns of Kelantan and Terengganu (both UMS) were still essentially Malay. Indians were most numerous in the towns of the FMS, where they were very evenly distributed and formed just over one-fifth of the total urban population in each state. Race relations were good as far as they went. There had been no inter-racial friction, apart from Malay newspaper criticisms of Chinese and Indian immigration and of the growing economic disparities between Malays and non-Malays. Chinese criticisms against British protective measures on behalf of Malays, such as the Malay Reservations Enactment, were offset by major Chinese gains in the business and labour fields, while Indians were generally satisfied with gaining jobs in the public and private sectors and with the open atmosphere for business opportunities. However, Indian business enterprises were still small-scale, confined to money lending, shipping services such as stevedoring and ship chandling, textiles, and retail trade in towns and rural areas. But because Chinese numbers were far greater than Indians and Chinese business enterprises, more varied and challenging, the Chinese were seen by Malays as the greater threat to their economic and political future.

Table 1. Total Population of Malaya, 1921–47

Note: *The term “Malaysian” in the census reports means peoples of the indigenous races including Indonesian Malays and the aborigines.

Table 2. Number of Chinese and Indians Born in Malaya

Source: M.V. del Tufo, Malaya: A Report on the 1947 Census of Population (London, 1949), pp. 40, 84–5.

The Malay Sultans and their subjects were opposed to unrestricted immigration of Chinese and Indians, but since British policy was nominally protective of and generally favourable to Malay interests, their discontent was stifled. British rule in the FMS left the traditional and regional elites with a certain degree of autonomy. In both the FMS and UMS, however, the British controlled the government, foreign affairs, and defence, while Malay customary law and the Islamic religion were in the hands of the Sultans. The British gave preference to Malays for employment in government service: only Malays were eligible to enter the elite Malayan Civil Service through which the British governed the country, and in 1913 a Malay Reservations Enactment was passed to prevent non-Malays from acquiring additional agricultural lands.2 Only selected Malays, mostly of aristocratic background, were given higher education and groomed for high administrative posts in the civil service. Malay vernacular education was encouraged up to primary level, with emphasis on agriculture, handicraft, and educational fundamentals. Limited attention was paid to Malay agriculture, but British policy remained largely paternalistic and until 1941 was aimed at preserving the traditional Malay society behind walls of British protection.

Malayan economic development was restricted to the colony’s two great industries, tin and rubber, supplemented only by the thriving entrepot trade of the Straits Settlements. Ownership of the rubber and tin industries was shared primarily between the British and the Chinese, with the former holding the major share. Towards the end of the last century, the British had broken into the Chinese monopoly of tin and the trend in the 1930s was increasingly towards greater degree of British control. Before the First World War, the British controlled only a quarter of the tin, but with the introduction of colossal machine dredges after the war, British production mounted sharply, until in 1929 it came for the first time to represent more than half of the total. By 1931 it had risen to 65 per cent.1 In rubber there was a similar pattern. In the 1930s the largest rubber estates were in the hands of Europeans, those in the middle group in the hands of Chinese, and the smallest in the hands of Chinese, Malays, and Indians.

The major economic effect of British rule in Malaya was the growth of a dual economy. On the one hand there was the modern colonial sector dominated by three industries: trade, rubber, and tin. On the other there was the more traditional sector, most easily classified as the Malay peasant sector and concentrated in the UMS of the north and east. Smallholdings of rice, rubber, or coconut, characterized the latter. Up to 1941 there had been little modernization of peasant agriculture. Malaya was still a net importer of rice. Under the pressure of the expanding rubber industry, rice cultivation was given low priority. In 1935 only 300,000 tons or 40 per cent of the rice consumed in Malaya was produced inside the country, the bulk in the less developed UMS of the north. The remaining 60 per cent was imported from Siam, Burma, and elsewhere. The peasant sector has always been nearly self-sufficient in rice, while imports have been largely for the urban areas.2

Education

Maintenance of ethnic plurality was best seen in the schools, the most important social institution for the preservation of multiple cultural identities. There were four main and separate streams of education perpetuated through the efforts of the government, the Christian missions, and the independent Chinese school boards. While the missions devoted their efforts largely to giving education in the English medium (in which venture the government also had a part), the government more particularly sponsored Malay education. However, except for the Malay College, Kuala Kangsar (MCKK) which prepared high-ranking Malays for entry into the administrative government service, and two teachers’ colleges (one for women in Malacca), there was no Malay secondary education to speak of, except those of a religious nature acquired in the Middle East. There were also Malay village schools, such as the sekolah ugama (religious schools where the Koran was taught), but the colonial government did not subsidize these schools.

Indian schools up to primary level were provided on the estates under a government regulation of 1912, most of them using Tamil as the medium of instruction. The Chinese, however, were left on their own. They built and financed their own schools up to the secondary level and introduced their own curricula in Mandarin (Kuo Yu, the Chinese national language). Most of the teachers were recruited from China. It was not until 1920, when the colonial authorities discovered that Chinese schools were involved in the politics of the Chinese nationalist movement, and were being used to inculcate Chinese patriotism and anti-British ideas, that legislation was introduced for the registration and control of Chinese schools and teachers. This move was strongly opposed by Chinese schoolteachers. Agitation died down, however, when the legislation was accompanied by a scheme for grants-in-aid for Chinese schools. Although the government was able to control the teachers through an inspectorate and dissuade them from teaching overtly political subjects, it did not yet consider it necessary to revise the curricula or the textbooks used in the Chinese schools. The textbooks were about China exclusively; there was no mention in them of Malaya’s history, geography, or the cultures of its mixed population.3 The colonial regime was preoccupied with education in Malay and English. The emphasis on English, while meeting the demand of some Chinese and Indian parents for Western education, also served to provide the British business houses and the administrative service with clerks and office workers.

The only really national schools up to secondary level were the English schools, which instructed children of all ethnic groups and gave them a common curriculum. These schools were, however, heavily oriented towards English culture and history, especially the history of the British Empire.4 More non-Malays than Malays attended English schools. One reason for the poor Malay attendance was that early English schools were run by Christian missionaries; the schools were also in urban centres far from the villages and were dependent on fees which most Malay peasants could ill afford. Only in the 1930s when the government began building secular English schools in the FMS for all races were Malay children urged to attend. Because of the large proportion of Chinese pupils in English schools in both the FMS and the Straits Settlements, Chinese began to push for the establishment of an English-medium university. In 1905 they succeeded in getting the government to establish the King Edward VII Medical College in Singapore, and hoped that this would be the nucleus of a university. In 1921 Raffles College, which taught subjects mainly in the humanities, was opened. Students who enrolled at both colleges were overwhelmingly Chinese and Indians. This led certain influential British administrators such as the Malay scholar and first principal of Raffles College, Richard Winstedt, to believe it was premature to establish a Malayan university, especially as Malays would find no place in it. Consequently, the government resisted Chinese pressure to combine both colleges into a university, despite a Chinese undertaking to raise funds for the project. The University of Malaya was only established after the Second World War.3

While the FMS government’s preferential “pro-Malay” policy enabled Malays to get into the lower and middle rungs of government service, there were fewer opportunities for non-Malays to join the civil service. Small numbers of Chinese were recruited into the government clerical service in the FMS, while Indians were recruited into the clerical sections of the Railways and Harbour Departments, which, like the rubber estates, used a greater pool of Indian labour. In 1934 the Straits Settlements Civil Service was formed which was open at the bottom to Chinese or to anyone else born in the Straits Colony.

Nationalism

Ethnic diversity, economic and cultural diversity, and diversity in the educational system were bound to produce a diversity of nationalist movements in Malaya. The origins of each movement will be discussed under each racial group.

The Malays

In the nineteenth century and early twentieth century, there had been a succession of Malay revolts against British rule, the last in 1928 in Terengganu. The British had crushed each revolt, reminding some Malays of the early defeat of the Melaka sultanate at the hands of the Portuguese in 1511. Despite what many British administrators have written, the Malays never welcomed British rule; it was always seen as interference in their political affairs.

Once the Malay rulers decided they had to come to terms with British power, they entered into treaties with the British, whereby the British undertook to “protect” their states, take over administration, and look after Malay welfare, defence, and foreign affairs, leaving only the Islamic religion and Malay custom in Malay hands. It was on the basis of these treaties that Malay leaders subsequently condemned the British for neglecting their interests and for allowing increased Chinese economic dominance in the FMS. Malay economic discontent led to a greater political consciousness among Malays and to the development of a Malay nationalist movement.

Foreign political influences also helped to fan nationalist feelings among the Malays. The reformist movement in Islam in the Middle East, during the first two decades of the twentieth century, had an impact on Malaya. Malay and Sumatran students who had studied either at Mecca or at Al-Azhar brought these ideas back. This led to the doctrinal debate between the Kaum Muda (the modernists) and Kaum Tua (the traditionalists), which extended to social and economic questions. The Kaum Tua, backed by the Malay aristocracy and the Brit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Epigraph page

- Title page

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Illustrations

- List of Appendices

- Abbreviations

- Note on Malay Spelling and Currency

- Preface to the Fourth Edition

- Foreword to the Third Edition

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- PART I: THE ROOTS OF THE CONFLICT

- 1. Malaya’s Plural Society in 1941

- 2. The Social Impact of the Japanese Occupation of Malaya, 1942–5

- 3. The MCP and the Anti-Japanese Movement

- 4. The Malay Independence Movement

- PART II: THE CONTEST FOR POSTWAR MALAYA, 1945–6

- 5. The Post-Surrender Interregnum: Breakdown of Law and Order

- 6. The MPAJA Guerrillas Takeover

- 7. Outbreak of Violence and Reign of Terror

- 8. The Malay/MCP/Chinese Conflict

- 9. Conflict between the Communists and the BMA

- 10. The Malay-British Conflict

- 11. Conclusion

- Appendices

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

- Copyright page