![]() Part One

Part One![]()

1

Leslie and Myrtlewood

As with most legends, there was an element of fiction in his life.

—Arnold Kirkpatrick in the Thoroughbred Times

One afternoon in the spring of 1949, Leslie Combs turned his Lincoln Continental off Ironworks Pike and drove through the wrought-iron gates up the hill past the dogwood-lined paddocks of Spendthrift Farm. At the top of the hill, in front of his eighteenth-century mansion, he had a good view of his farm and the mares and foals grazing there. His mares, the ones that started this place. He wanted them to be the first thing he saw whenever he came back to the farm, to be reminded of why he returned to Kentucky, why he bought this land, and what he yet hoped to accomplish here.

Leslie shut the car door and strode into the house. In the thirteen years he’d been back in Kentucky, he had made Spendthrift a force to be reckoned with. His yearlings were among the most sought-after at all the major sales, but getting to the top hadn’t been easy. Without access to the best stallions in the Bluegrass, finding them closed to new breeders, he bought his own and sold shares in them to investors. Leslie’s ingenuity and powers of persuasion had already landed the young stallion Alibhai, bought for half a million dollars from movie mogul Louis B. Mayer, in Spendthrift’s breeding shed, where he would eventually sire Kentucky Derby–winner Determine as well as fifty-four stakes winners.

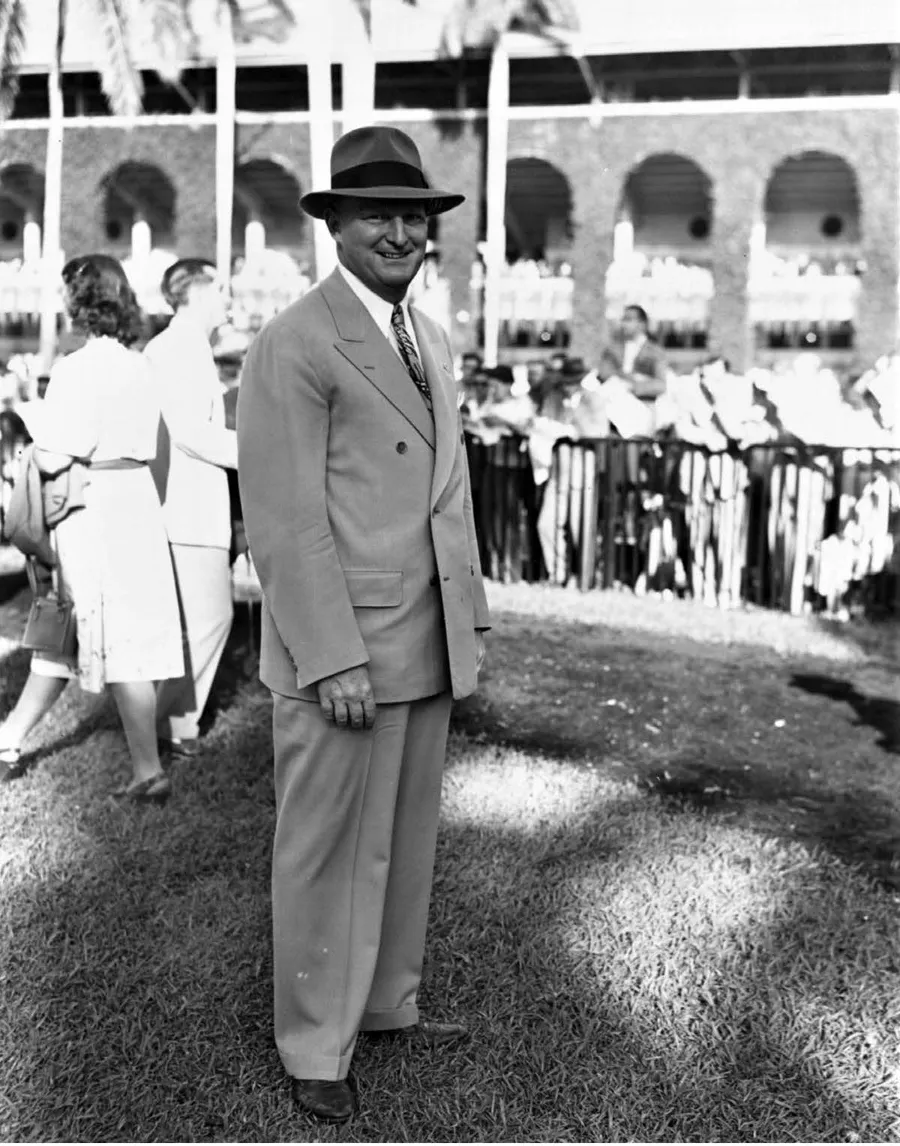

Tall, slim, and alternately charming and irascible, Leslie was skilled at getting what he wanted. He made people feel he was doing them a favor while steering them toward his own desired goal. His charisma engendered decades-long relationships with clients in the top tier of business, entertainment, and society like Mayer, Harry Guggenheim, John Hanes, and Marshall Field III. He entertained on a large and lavish scale, creating a world at Spendthrift so alluring that even the rich and famous wanted to be part of it. But he was careful not to overindulge while entertaining—he would drink a Virgin Mary or plain tonic with lime to maintain an edge over his clients. Frequently tanned from winters at Hialeah and Bal Harbour, his face was taut and lean, and his eyes darted hawklike behind his glasses, narrowed in intense focus when examining a yearling in a barn or auction ring. He spoke in a raspy voice and liberally used the word “boy” and the n-word when dealing with subordinates. He was a legendary and unabashed womanizer who would “flirt with every young thing that came by” and poke women with his cane made from a dried and varnished bull penis. One of his best and earliest clients, cosmetics magnate Elizabeth Arden Graham, “knew he was a terrible rascal” but relied on his sage advice for years when buying yearlings, resulting in Kentucky Derby–winner Jet Pilot in 1947. He kept his only son, Brownell, at arm’s length, shipping him off to military school while at the same time making prospective clients feel so much like family that they dubbed him “Cuzin’ Leslie.” He was an opportunist who had married money. Always impeccably dressed, often in a tweed coat, necktie, hat, and pocket handkerchief, Leslie was a showman, shrewd enough always to practice a broad smile for the camera.

Leslie removed his hat and settled into a wicker chair in his sunroom overlooking a stone patio and a pool, where he could have a glass of grapefruit juice on ice and look out on his broodmares in pasture. On this side porch, Leslie often entertained clients, spreading rolled oats on the surrounding pastures to keep mares and their foals where clients could see them and dream of owning one. The jewel among them was the foundation mare Myrtlewood, now seventeen, with her filly by Bull Lea at her side.

Leslie Combs at Hialeah, 1947. (Keeneland Library, Morgan Collection)

If a single horse could be the symbol of what Leslie hoped for and eventually achieved, it would be Myrtlewood. Without her, Spendthrift would not be Spendthrift. Leslie could never have accomplished what he did without her, and he knew it. Foaled at his uncle Brownell’s Belair farm in southern Fayette County, Myrtlewood was the first champion bred by the Combs family, and the first horse to be named champion sprinter in 1936. She set two American records for females and held records at five different tracks. In twenty-two starts, she won fifteen times, and she was out of the money only once in her career. She beat Seabiscuit once in Detroit’s Motor City Handicap, where she broke the track record under wraps as the highweight and heavy favorite, conceding twelve pounds to the Biscuit. After that victory, sportswriter Lewis H. Walter called her “the greatest racing mare on the United States turf today.”

As the magnificent dark bay champion, now a little swaybacked after ten foals, moved with her new filly to the next patch of fresh grass, Leslie saw the flash of one small white sock on her left hind. Her conformation was nearly perfect, with power, good bone, and graceful proportions, as turf writers from her racing days had noted. Generally calm and unruffled, the mare had a quiet temperament and never liked the whip. When a mockingbird chattered in the distance, Myrtlewood raised her head, revealing her forehead with its brief white comma-like strip that didn’t quite meet up with the long narrow one that ran down the middle of her face. The markings on Myrtlewood’s face reminded Leslie of his own life: how he’d started out in the Bluegrass, been interrupted, then came back for a long stretch he expected to last the rest of his days.

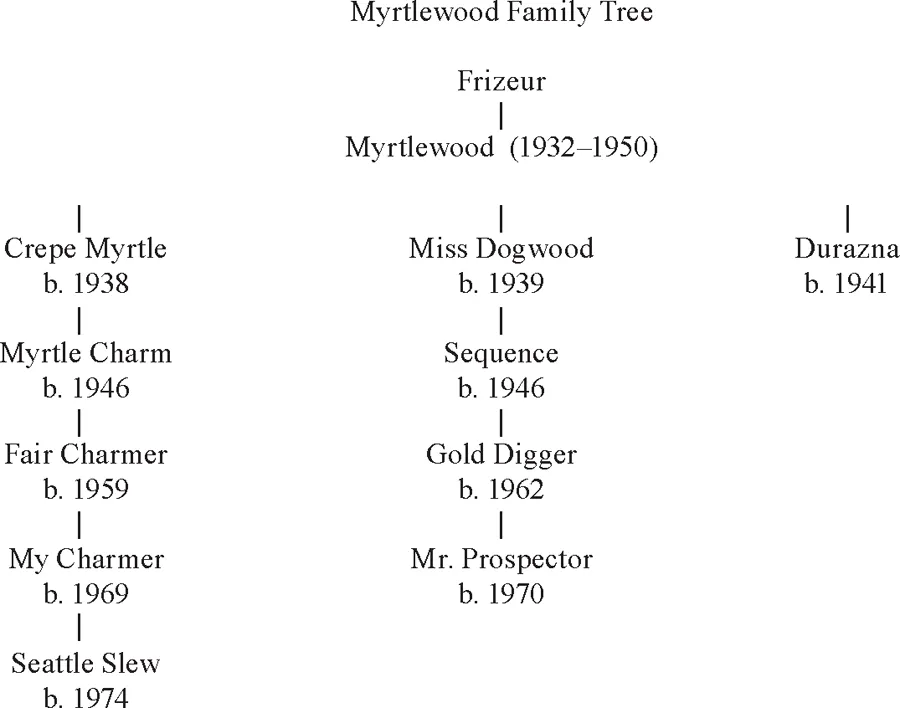

Incredibly, Myrtlewood surpassed her success at the track with her production as a broodmare. Her first two fillies, Crepe Myrtle and Miss Dogwood, would make Myrtlewood one of the most important foundation mares of the American Thoroughbred and ensure the success of Leslie and Spendthrift for years to come. Crepe Myrtle produced Myrtle Charm, the first champion bred in Leslie’s own name. Her daughter Fair Charmer produced My Charmer, who, when bred to Bold Reasoning, would foal none other than Seattle Slew. Myrtlewood’s second filly, Kentucky Oaks–winner Miss Dogwood, already had foaled the good stakes-winning mare Sequence, who would become a beacon in the dazzling Myrtlewood female line when her daughter Gold Digger produced one of the greatest sires in history, Mr. Prospector.

Leslie set down his drink and went into his office. On its walls hung an oil painting of Myrtlewood in pasture with Miss Dogwood. Next spring, when Myrtlewood breathed her last at age eighteen on Saint Patrick’s Day, the painting would serve as a reminder of the great mare and all he owed her. Leslie buried her among the roses outside his office window, where he thought he would be near her as long as he lived.

Leslie poured himself another grapefruit juice and returned to the sunporch. From here, he could look past his own land across Ironworks Pike, to the beautiful farm so full of history bought and christened Elmendorf by his great-grandfather Daniel Swigert. Leslie named his farm Spendthrift in honor of the yearling Swigert bought for one thousand dollars, who went on to win the 1878 Belmont Stakes and become the great-grandsire of Man o’ War. Swigert sold Elmendorf ten years before Leslie was born, and the farm had changed hands several times since. Now it was known as the Old Widener Farm, and Leslie often crossed Ironworks Pike to visit there, determined to buy it back someday.

Leslie took another sip of his drink, his gaze still fixed across the road. Looking towards Paris Pike, Leslie could see the land where his own father worked as a dairy farm manager, tending cows for tycoon James Ben Ali Haggin after he acquired Elmendorf. As a child, Leslie didn’t know how low his father Daniel had fallen, tending cattle on a farm he might have once inherited. Leslie, a direct descendant of the founder of Elmendorf, was growing up the son of a stockman. He was too young to understand why his father parted company with Haggin and took the family away from the Bluegrass. Lying in bed at night, he could hear his parents argue about money, but he didn’t know his father was depressed by debts he couldn’t pay or that he’d been fired and was unable to find another job. When, at age thirty-seven, Daniel was shot in the right temple, no one told his son it was suicide. Even the newspapers said it was an accident.

After the funeral, Leslie’s mother, Florence, now nearly penniless, sent her son to live with relatives in her hometown of Lewisburg, West Virginia, where he attended Greenbrier Military School. Between his years in Tennessee at the cattle ranch, and those in the strict academic environment in West Virginia, Leslie felt further and further removed from the Bluegrass. But even in his young heart, he always knew he would come back.

Anyone even mildly acquainted with Leslie knew he could never sit still. Always restless, he radiated energy. Rattling the ice in his glass, he left the sunporch, passing a portrait of his grandfather, Hon. Leslie Combs, in the hallway. His grandfather did two things that paved the way for Leslie to found Spendthrift Farm. First, he married Mamie Swigert, the wealthy daughter of Daniel Swigert, uniting the two families. Second, shortly after Swigert sold Elmendorf, Hon. Leslie acquired Belair.

Hon. Leslie and his son, Brownell, stood their own stallions and imported broodmares from England at Belair. Sixteen years his senior, Brownell became a solid and enduring presence in young Leslie’s life, comanaging Belair as Hon. Leslie aged. Brownell bred his first stakes winner at Belair when Leslie was just eighteen. While Leslie was in his twenties, Brownell acquired the mare Frizeur, a daughter of Frizette. When Brownell decided to breed Frizeur to Blue Larkspur in 1931, her next foal was none other than Myrtlewood.

As a young adult, Leslie felt the lure of the Bluegrass and developed a taste for parties and high society that would remain with him the rest of his life. He loved dancing with pretty girls and being around the wealthy. Hon. Leslie, who felt responsible for helping his grandson amount to something, nudged him toward a more productive path, insisting he enroll in college. After only a year at Centre College in nearby Danville, Leslie dropped out. Hon. Leslie responded by sending his young namesake to Guatemala to work on a coffee plantation, where he learned to speak Spanish and contracted malaria.

At this point in his life, Leslie may not have known exactly what he wanted to be, but he didn’t want to be poor or beholden to others. He was determined to be unlike his parents, living hand to mouth. He would be in charge of his own life, and one way or another, he would have money. After recovering at White Sulphur Springs spa in West Virginia, Leslie met the beautiful Huntington heiress Dorothy Enslow. His marriage to Dorothy in 1924 provided Leslie with the money and social connections he craved.

An added bonus was that Dorothy’s mother, Juliette, loved horses and racing. The couple frequently accompanied her to the track at Charles Town, and Leslie eventually became chairman of the West Virginia Racing Commission. With an infusion of Enslow cash and influence, Leslie started his own insurance company. Finally, Leslie seemed to be established, putting down roots in his wife’s hometown.

But things were about to change.

One Friday evening in October 1936, after a bridge party, Leslie’s mother-in-law, sixty-three-year-old Juliette Enslow, said goodnight to live-in housekeeper Elizabeth Bricker and went upstairs to bed with two massive diamond rings she always wore still on her fingers. When Bricker brought the elderly widow her breakfast tray the next morning, she found her dead on the floor with a towel twisted around her neck, her bed sheets and pillow soaked with blood, and the rings gone. Mrs. Enslow’s chauffeur, Judge Johnson, arriving to work, noticed an empty wallet on the front lawn. He went inside and woke Charles Baldwin, Juliette’s son from her first marriage, a forty-year-old army air captain and amputee, who had lived with his mother since his divorce. Johnson found it odd that Charles sprang immediately out of bed, with the prosthetic leg he usually kept at his bedside, already attached.

Eight hours later and more than a hundred miles away, four-year-old Myrtlewood went to post in the Ashland Stakes at the inaugural meet of newly opened Keeneland racetrack, for what was expected to be her last start. Carrying 126 pounds in the slop and conceding sixteen pounds to her rivals, the great mare romped, winning by twelve lengths.

On the face of it, his mother-in-law’s murder and the retirement of Uncle Brownell’s greatest race mare couldn’t possibly have anything in common for Leslie, but it seems his destiny was entwined with Myrtlewood’s: as the mare was ending her fabled career on the track, a family drama was about to unfold that would bring man and horse together in a fateful way and, in the process, create a Thoroughbred breeding empire.

Myrtlewood at Keeneland after winning the Ashland Stakes in 1936. (Keeneland Library, General Collections)

The murder of wealthy Juliette Enslow, originally thought to be motivated by robbery, created a sensation and became national news. A week later, Dorothy’s half brother Charles was charged with first-degree murder. Baldwin’s motive, according to investigators, sprang from his addiction to narcotics prescribed following the amputation of his leg, and administered by his mother from a supply kept in her bedroom drawer. Prosecutors theorized the widow was killed in a struggle when she refused Baldwin’s demands for more opioids and sought the death penalty for the handsome, well-liked former aviator. In March 1937, jurors deliberated less than two hours to find Baldwin not guilty. The crime was never solved.

By September, Leslie had moved his family back to this 127-acre farm on Ironworks Pike. Myrtlewood, a gift from Uncle Brownell to his nephew, left her birthplace at Belair and moved there too, carrying her first foal, Crepe Myrtle, who would become the fourth dam of Seattle Slew. Myrtlewood and Leslie would start out in the business of breeding future champions together. Things were coming full circle: Leslie’...