![]()

1 History, Archaeology and Culture

F. Spagnoli1* and A. Yavari2

1Department Italian Institute of Oriental Studies - ISO, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy; 2Pomologist and Consultant, Tehran, Iran

1.1 Introduction

It is said that a basket of figs was enough for Cato the Censor to convince the reticent Senators of Rome of the need to destroy Carthage. Libyan figs were sold fresh in the city market. ‘The land that produced them is only three days away from Rome’, Cato said, coming back from a diplomatic mission to the African metropolis in 150 BCE (Pliny the Elder, Naturalis Historia 20:1–3). With this demonstration, Cato did not just want to show the proximity of Carthage to Rome. He also wanted to represent the vast wealth due to the flourishing agricultural activity in the fertile North African hinterland of the Punic city symbolized by the sumptuousness of these fruits. The fig (Ficus carica L.) is a fruit that evokes, in the collective imagination, the generosity and fruitfulness of nature that nourishes man with its spontaneous fruits even before man domesticated and cultivated plants and fruit trees.

1.2 Etymology

The names given through the centuries to the fig have a direct relationship to their origin and distribution. The Latin Ficus comes from an earlier Indian stem word such as fag or the Hebrew feg, the Italian fico, the Portuguese figo, the Spanish higo, the French figue, the German Feigen, the Dutch vijg and the early English figge or fegge, later simplified to ‘fig’. In Greece, the wild fig was called erineos, and the edible fig was known as sykon from which is derived ‘syconium’, the botanical name of the fruit. The edible fig was called Teena in Hebrew and in Aramaic, tena, Arabic tin, Phoenician paggim, North Syrian pagga, and Persian anjir (Condit, 1947).

1.3 Domestication, Dispersal and Archaeological Evidence of the Fig

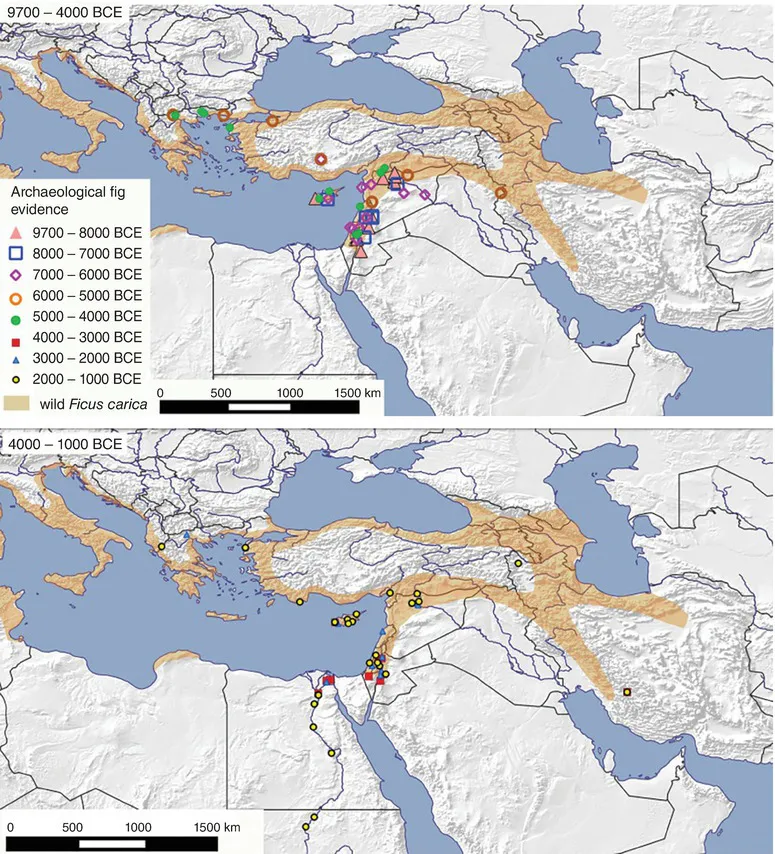

The fig, Ficus carica L. (Moraceae), is the third classical fruit crop associated with the beginning of horticulture in the Mediterranean basin and south-west Asia (Zohary and Spiegel-Roy, 1975). This common fig (based on the evidence available) has been a part of food production in this region since the Early Bronze Age period, providing fresh summer fruit and storable, sugar-rich, dry figs throughout the year. The domesticated fig tree exhibits a close morphological resemblance, striking similarities in climate requirements and close genetic interconnections with an aggregate of wild and weedy fig types distributed throughout the Mediterranean basin (Fig. 1.1) (Zohary et al., 2012).

Fig. 1.1. Geographical distribution of the wild fig, Ficus carica L. (figure used with permission from Zohary et al., 2012).

Under domestication, the plants grew vegetatively through the rooting of winter dormant twigs of female individuals selected for their desirable characteristics, and occasionally through grafting. The main changes in this fruit crop under domestication were the shift to the vegetative propagation of female clones for: (i) an increase in syconia size, flesh and sugar content; (ii) the introduction of artificial pollination and caprification; and (iii) the successful selection for parthenocarpy, which eliminates the pollination required for fruit set (Zohary et al., 2012).

By the fourth millennium BCE F. carica was cultivated in the Nile Delta, although it remains unclear where in the Nile Valley native sycamore fig (Ficus sycomorus) was originally distributed, or how early it was cultivated (most likely through vegetative propagation) (Fig. 1.2) (Fuller and Stevens, 2019).

Fig. 1.2. Archaeobotanical finds of the fig in West Asia, North Africa and adjacent regions (mainly Ficus carica but potentially also Ficus sycomorus especially in North Africa) compared to the common fig’s (Ficus carica) wild distribution. Sites are shown in millennium blocks from 9700 to 4000 BCE above, and from 4000 to 1000 BCE below. (Figure used with permission from Fuller and Stevens, 2019.)

1.4 Fig in Ancient Egypt

Cultivation of the sycamore fig, Ficus sycomorus L. (Moraceae), was almost exclusively an Egyptian specialty. Compared with the common fig, F. carica, it is a larger and taller tree, but produces smaller, inferior syconia. Since the Early Dynastic period, at end of the 4th millennium BCE, the sycamore fig was (and still is) a common fruit crop and a valued timber source in the lower Nile Valley (Zohary et al., 2012). In Egypt, the earliest archaeobotanical record of figs is from Tell el-Fara’in (ancient Buto) in the Nile Delta in the Predynastic period (ca. 3650–3450 BCE: Thanheiser, 1991).

One of the most ancient paleobotanic attestations of fig fruits comes from the oasis of Kharga in Egypt, where early cultivation of figs was documented at the end of the Palaeolithic Era (Caton Thompson, 1952, p. 117).

After its complete domestication, at the end of the 4th millennium BCE, the fig acquired a strong symbolic value alluding to fertility during the First Egyptian Dynasty (3100–2900 BCE). With the palm tree, it was considered the tree of life and it was linked to Osiris, one of the most important deities of the Egyptian pantheon (De Rachewiltz, 1982, p. 147). For this reason, fig trees (F. sycomorus) adorned the courtyards of royal palaces and temples of the Pharaoh and temple and tomb decorations.

In Memphis there is a sycamore fig tree near the temple of Ptah in Karnak (Luxor), where, according to tradition, the goddess Hathor feeds figs to the dead as she rises from the trunk (Gillam, 1995, pp. 221–222). In Egypt, the sycamore was called nehet, a term whose root, neh, indicates protection while the female nehetet designated the goddess Hathor. In the Book of the Dead (ch. CLXXXIV), we read: ‘Let me feed on the Sycamore of the goddess Hathor’. This scene is often reproduced with the holy buckets of milk and water used in fertility cult ceremonies.

A beautifully preserved drawing of a fig harvest has been found in the Tomb of Khnumhotep (Early 12th Dynasty, ca. 1950 BCE) at Beni Hasan depicting farmers training monkeys to climb trees and harvest them (Darby et al., 1977).

The F. sycomorus tree is depicted in a decorative fragment from the tomb of Nebamon, an official who lived at Thebes under the reign of Thutmose IV (1401–1391 BCE), and Amenhotep III (1391–1353 BCE). The fragment, now in Londons’s British Museum (TT146), depicts the garden to cheer the souls of the deceased. The garden, in which trees, flowers, birds and fish are meticulously represented, develops around a swimming pool. Among the trees, arranged in an orderly sequence, one can recognize the palm and the sycamore fig. This representation is perhaps inspired by the bas-reliefs of the earlier ‘Syrian Garden’ of Thutmose III (1479–1424 BCE) at Karnak. The fig is also one of the preferred foods for the journey to the afterlife; often consumed at banquets honoring the deceased. Such a banquet is shown in the almost contemporaneous wall painting of the Tomb of Nakht, a scribe who lived during the reign of Thutmose IV (TT152, Necropolis of Sheikh Abdel-Qurna: Seidel and Ghaffar Shedid, 1991).

In the Tell el-Amarna period (second half of 14th century BCE), representations of figs can be seen in numerous pharaonic reliefs describing scenes of everyday life of the Pharaoh and family. Here figs are served with pomegranates as both indicate the high status of their consumers and wealth and abundance of the land that produced them. Egypt was known for its figs.

A basket of figs held the fate of Cleopatra, the last Pharaoh of Egypt. Plutarch wrote the Queen had hidden the snakes with which she intended to kill herself in a basket of big and juicy figs: ‘It is said that the asp was brought to Cleopatra in the basket together with the figs and that she had given orders to hide it among the leaves so that the reptile would bite her without her noticing. But when she removed the figs, she saw it, and said: “There it is, you see”. She, therefore, bared her arm and offered it to the bite of the animal’ (Plutarch, Life of Antonius, 86).

1.5 At the Beginnings of Civilization: The Fig in Neolithic Levant and East Mediterranean

In the Neolithic period, wild fig fruits were an essential part of the human diet. Therefore, man rapidly successfully cultivated them. One of the earliest proofs of domestication is attested to the Levant. In the Neolithic village of Gilgal, in the Lower Jordan Valley, numerous remains of stored carbonized figs dating to the 8th millennium BCE have been found. Gilgal figs belong to a mutant parthenocarpic variety, lack embryonic seeds and were probably vegetatively propagated through planting cuttings. Figs are, therefore, the first domesticated and cultivated plant, preceeding even cereals. Gilgal figs were grown with other plant foods; wild barley (Hordeum spontaneum), wild oats (Avena sterilis), and acorns (Quercus ithaburensis). The early Gilgal farmers, therefore, had a double subsistence strategy, the collection and conservation of wild plants, and early domestication of the fig tree. This type of economy was widely practiced during the Neolithic period in Mesopotamia and in the Levant (Kislev et al., 2006).

However, along the coasts of the eastern Mediterranean, domestication of the fig occurred centuries later. These regions had the closest wild ancestor of the cultivated fig, Ficus palmata L., which is the wild F. carica variety of the Levant, South Turkey and Aegean area. It is thought to be the most likely ancestral species of the early domesticated fig. The temperate climate with abundant autumn and spring rains was a favorable element for fig, vine and olive cultivation. The association with grapes is meaningful, as figs were needed to trigger wine fermentation. For this reason, the fig played a cultural role in this area, being considered an essential element of the daily diet, nutritious, and easily preserved. In the later Minoan, Mycenaean and Phoenician maritime societies, dried figs were food on long Mediterranean voyages.

1.6 The Role of the Phoenicians: Figs in Greece and West Mediterranean in the Iron Age

From the Near East and the Levant, Phoenicians carried F. carica to the western world via two distinct routes. Following the Phoenician route via the larger islands of the Mediterranean; Cyprus, Rhodes, Crete, Malta, Sicily, Sardinia, and Corsica; fig culture reached the central and western regions of the Mediterranean and beyond through the Pillar of Hercules on the Portugal coast. From the coasts, the material and immaterial knowledge, customs and traditions of the Phoenician culture seeped inland. Multiple fig tree species had been carried since the beginnings of the Iron Age. In the early stages of diffusion, the tree and its fruit were initially a luxury for the élites. Later, as figs are rich in sugar and carbohydrates, and able to be consumed fresh, dried, in jams or with honey, they were an important component of the daily diet (Mata Parreño et al., 2010a). In Phoenician and Punic sites, whole figs and partial figs have been found in funeral offerings as symbolic nourishment in the afterlife, and in domestic contexts. Fig seeds have also found in the same domestic contexts and in pits. The presence of seeds may have been accidental. The fleshy, juicy fig fruit decomposes easily. Perhaps the seeds remained in archaeological deposits or in silos after ritual funeral or domestic fires.

Generally, in archaeological layers, it is more frequent to find the fruits rather than the wood, suggesting the great importance of fig production and less use of the wood itself as firewood. Fig is low quality, brittle, coarse-grained, pithy wood, and smokes with burning. Its bark secretes a white latex that irritates the skin but which, if mixed with milk, produces vegetable rennet. In Phoenician and Punic art, iconographic representations of the fig tree or its fruits are quite rare. Nevertheless, they played an important role in the Phoenician imagination, as they were appreciated in everyday life and also as nourishment and gifts for the afterlife, as evidenced by the offering of whole figs in graves. Figs were widely spread throughout the Mediterranean by the Phoenicians. For them figs were not only a luxury when fresh and ripe but also as an important dried diet staple during the winter months (Bartoloni and Guirguis, 2017).

The first mention of figs in Greece is in the Odyssey; in Book 7 figs are described in the land of Phaeacians. However, these verses citing the figs were probably interpolated much later. The earliest genuine...