- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this fully illustrated introduction, leading Vietnam War historian Dr Andrew Wiest provides a concise overview of America's most divisive war.

America entered the Vietnam War certain of its Cold War doctrines and convinced of its moral mission to save the world from the advance of communism. However, the war was not at all what the United States expected. Dr Andrew Wiest examines how, outnumbered and outgunned, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces resorted to a guerrilla war based on the theories of Mao Zedong of China, while the US responded with firepower and overwhelming force. Drawing on the latest research for this new edition, Wiest examines the brutal and prolonged resultant conflict, and how its consequences would change America forever, leaving the country battered and unsure as it sought to face the challenges of the final acts of the Cold War. As for Vietnam, the conflict would continue long after the US had exited its military adventure in Southeast Asia.

Updated and revised, with full-colour maps and new images throughout, this is an accessible introduction to the most important event of the "American Century."

America entered the Vietnam War certain of its Cold War doctrines and convinced of its moral mission to save the world from the advance of communism. However, the war was not at all what the United States expected. Dr Andrew Wiest examines how, outnumbered and outgunned, the North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces resorted to a guerrilla war based on the theories of Mao Zedong of China, while the US responded with firepower and overwhelming force. Drawing on the latest research for this new edition, Wiest examines the brutal and prolonged resultant conflict, and how its consequences would change America forever, leaving the country battered and unsure as it sought to face the challenges of the final acts of the Cold War. As for Vietnam, the conflict would continue long after the US had exited its military adventure in Southeast Asia.

Updated and revised, with full-colour maps and new images throughout, this is an accessible introduction to the most important event of the "American Century."

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

THE FIGHTING

Battles of attrition

Strategies

Though the Vietnam War had been years in the making, in many ways the final commitment of US combat forces to defend South Vietnam had come as something of a surprise to Johnson and his advisors. The newly arrived force had as its goals the defense of the US base at Da Nang and the continued independence of South Vietnam. However, there were no distinct plans or even a truly concrete idea in the minds of the administration or the military concerning how to achieve those goals.

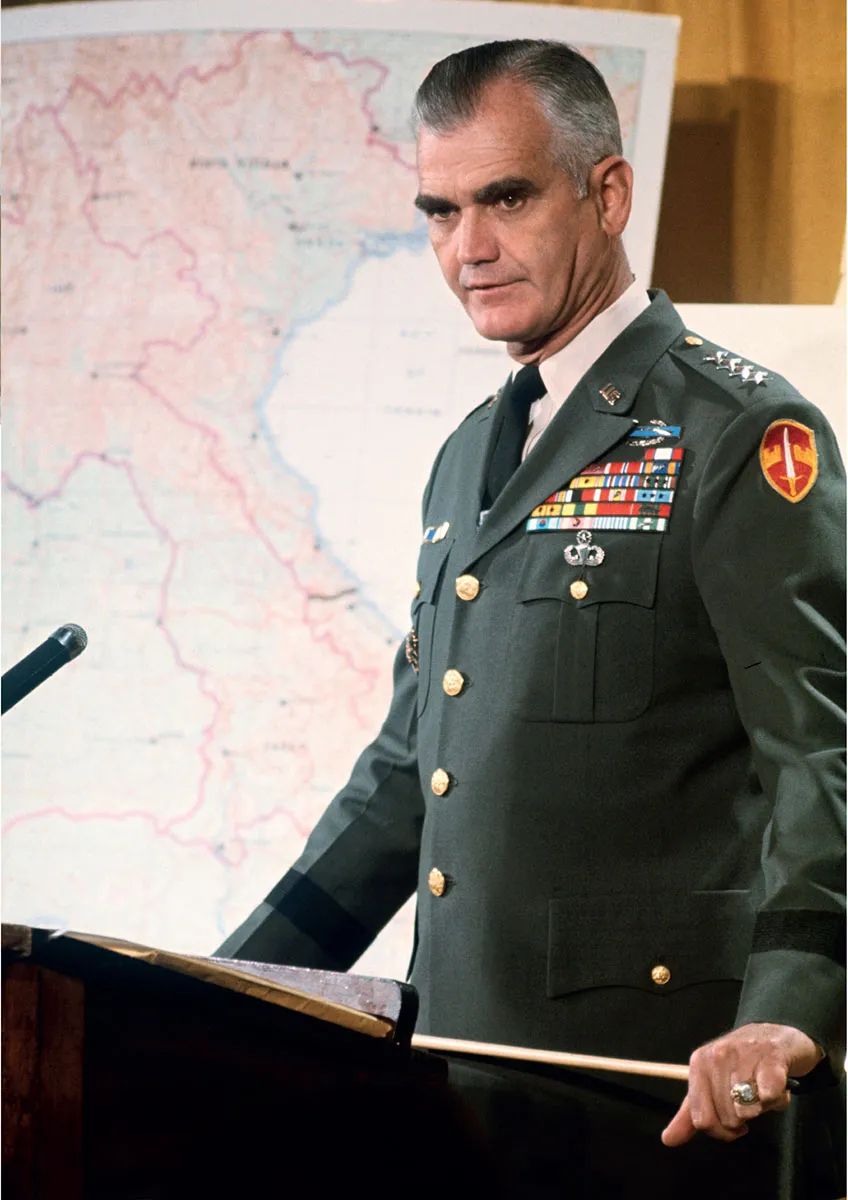

Westmoreland welcomed the commitment of US troops but felt that many more were needed. The US maintained important, vulnerable bases all over South Vietnam and he also expected a major ground offensive from North Vietnam. For these reasons he immediately increased his request for troops, and by June 1965 the American troop ceiling in Vietnam had been raised to 220,000, a considerable jump in only four months.

General William Westmoreland, commander of US forces in Vietnam, and architect of the American policy of attrition known as “search and destroy.” (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Johnson did not want his war in Vietnam to damage the great consensus for social change. He also realized that a full mobilization of US troops would be provocative in terms of the Cold War. Thus Johnson chose not to call up the National Guard or trained reserve, relying instead on a draft system to provide troops for the growing war. This decision was perhaps one of Johnson’s greatest blunders, for the draft was riddled with loopholes allowing the privileged to avoid military service, and became a lightning rod for national criticism of the conflict in Vietnam. In addition the US military opted for a one-year tour of duty in Vietnam in an effort to limit the exposure of soldiers there to the effects of combat. This well-intentioned move also backfired. After the initial troop deployment soldiers rotated into and out of Vietnam singly, joining units as replacements and leaving when their tour was up, a practice that crippled institutional memory and small unit loyalty in Vietnam. A soldier joined a unit of veterans that he did not know, and toward the end of his tour he would become a victim of “short timer’s fever.” As a result, for many men the war in Vietnam developed into one of solitary desperation and they sought simply to survive for a year and then return home. Nevertheless, the vast majority of Vietnam-era draftees fought with dogged determination and great gallantry.

However, in 1965 the problems of Johnson’s military system were in the future. Westmoreland had the finest military in the world and had to develop a plan to defeat the communist enemy. His strategic choices were limited by Johnson’s decision to confine US ground forces to South Vietnam. Under these frustrating restrictions Westmoreland hit upon a rather simple strategy to win the war. He planned to destroy the Viet Cong insurgency by wiping out its military cadres using the tactics of “find, fix and finish.” Knowing that the enemy was elusive, Westmoreland planned to locate enemy forces using superior intelligence. Then operational mobility would enable US forces to surprise the unsuspecting communists and lock them into battle. Once engaged, US forces could call down the might of their massive artillery and air support to destroy their foe. Westmoreland believed that the annihilation of major enemy units would show the North Vietnamese the error of their ways, thus allowing South Vietnam to exist in peace. Recent histories of the war indicate that Westmoreland did not completely overlook the vital alliance with South Vietnam or the growth of the war of counterinsurgency on the local level, but he remained fixated on the “big unit war” and the tactics that would become known as “search and destroy.” Through the might of America’s main force units Westmorland hoped that victory could be won rather quickly and easily, with American forces being withdrawn within three years.

Members of the 7th Cavalry fought a bitter struggle against NVA forces in the opening battle of US air mobility in the Ia Drang Valley. (US Army)

America thus chose to fight a conventional war in Vietnam believing that the application of superior force would achieve victory. Unfortunately, the Americans not only understood little about the tenacity and dedication of the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese, but also overestimated the ability of their own nation to withstand a protracted war. Ho and Giap once again chose to rely upon a drawn-out war of attrition to wear down the will of a superior enemy. Communist forces would avoid major confrontations with US units and would instead rely in the main on guerrilla tactics. Such action would cause the continuous, slow loss of American life in Vietnam. Over time, and with ample media coverage, the cumulative effect of the continued losses would make the United States question the value of its war in Vietnam.

The battle of the Ia Drang valley

In 1965 US and North Vietnamese military leaders were both looking to engage the other in battle, partly to learn each other’s strengths and weaknesses. For his part Westmoreland expected a communist attack in the Central Highlands near Pleiku on Route 19 designed to cut South Vietnam in two. The rugged terrain there seemingly gave the elusive enemy the edge – but Westmoreland was prepared. At nearby An Khe the 1st Air Cavalry stood ready to use air mobile tactics for the first time. The unit could use its 435 helicopters to carry soldiers into battle nearly anywhere in South Vietnam with great speed. Lavish fire support from artillery, helicopter gunships and aircraft ensured that the 1st Air Cavalry would pack quite a punch. This quick-moving, powerful force seemed to negate any possible terrain or mobility advantage the communists might seek to utilize.

Giap and the NVA local commander, General Chu Huy Man, on October 19 obliged Westmoreland by launching an attack on the US Special Forces camp at Plei Me involving the 320th and 33rd NVA regiments. The offensive was designed in part to seize Pleiku, but it was also designed to draw the Americans into battle. The communists realized that they were facing a formidable foe and had to learn the American way of war. To Westmoreland the attack on Plei Me presented a wonderful opportunity. The elusive enemy had been located in great strength and could now be fixed into battle for an attritional victory. Seizing his opportunity the US commander ordered the 1st Air Cavalry to hunt down and destroy communist forces in the area in the first test of air mobility.

Having been checked at Plei Me the NVA forces had retreated to the mountain fastness of the Chu Pong Massif bordering the Ia Drang Valley. On November 14 the two forces met in pitched battle. Helicopters bearing elements of the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Harold Moore, assaulted Landing Zone (LZ) X-Ray at the foot of the Chu Pong Massif – inadvertently landing in the midst of the NVA staging area. Even before the entire battalion arrived two NVA regiments, the 66th and 33rd, moved to surround the LZ and annihilate the tiny American force. As the battle raged helicopters brought in reinforcements under fire – but the Americans remained severely outnumbered. In savage, sometimes hand-to-hand, fighting the NVA nearly overran the American position, but was defeated by a murderous combination of small arms fire and artillery and air support. For three days the fighting raged around LZ X-Ray, which was no larger than a football field.

The struggle in the Central Highlands often involved VC or NVA forces attacking isolated US Special Forces outposts. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

The first major confrontation between US and NVA forces began on November 14, 1965 and pitted two battalions of the 1st Cavalry against more than 6,000 enemy soldiers.

It was in the battle of the Ia Drang Valley that US forces for the first time used their massive B-52 bombers, each carrying 36,000 pounds of high explosive, in a tactical role. Under the hail of fire on November 16 the North Vietnamese chose to break off their attack and retreat into the safe haven of Cambodia. Soon thereafter US forces also retreated from LZ X-Ray to make way for additional B-52 strikes. During this phase of the battle the 2nd Battalion, 7th Cavalry was ambushed and nearly destroyed while making its way through the dense terrain to LZ Albany. Sporadic fighting in the area took place until November 26 when the battle of the Ia Drang Valley officially reached its conclusion. During the struggle US forces had lost 305 dead. The NVA, though, had suffered greatly at the hands of US firepower losing an estimated 3,561 dead of a total force of 6,000.

The battle of the Ia Drang Valley was of critical importance as it set the precedent for the conduct of the war in Vietnam. The air mobility concept had proved its worth. In addition Westmoreland believed that Ia Drang validated his strategy of attrition, for American forces had inflicted an 11:1 loss ratio upon the NVA. The US commander hoped that it would not take many more such victories to push the communists to the decision to end their support for a war in the south. The communists, though, took quite different lessons from the battle. Though it had taken heavy losses the NVA believed the Ia Drang to be something of a victory because it had learned that it could in fact fight the Americans. The losses, though, convinced Giap to revert to a reliance on guerrilla warfare designed to inflict losses on the Americans before fleeing into Cambodia when their own losses became prohibitive. The tactical initiative, thus, lay with the communists. Even when facing air mobility it was the communists who decided whether to stand and fight or to flee to their safe havens, which gave them a critical edge in the conflict. In addition the NVA and the VC began to adopt the policy of “hanging on to American belts.” This policy called for communist fighters to get as close as possible to US forces before opening fire. If they were in close enough the Americans would refrain from using lavish artillery and air support for fear of hitting their own troops. In this way, Giap sought to avoid further Ia Drangs even as Westmoreland sought to replicate his victory there.

Viet Cong troops traverse the Ho Chi Minh Trail. The Trail, and safe havens in Cambodia and Laos, gave the communists a critical edge. (Photo by Sovfoto/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Other aspects of the battle of the Ia Drang Valley would go on to play a major part in the war and its controversial nature on the American home front. After the close of the battle US forces returned to their base camp at An Khe, thereby setting a pattern. US forces in Vietnam did not seize and hold enemy territory. Thus victory in the Vietnam War became more difficult for the American public to understand. Anxious relatives at home could not track the advance of US forces on a map. There were no breakouts from St. Lo or Inchon landings; instead victory in Vietnam came to be judged in the main in terms of “body count.” Though US forces would win every battle in the Vietnam War in these terms, to the American public it seemed that their troops fought again and again in the same places, taking no land and seemingly making no progress. Support for the conflict would begin to wane.

Search and destroy

By 1965 the worst of South Vietnam’s political problems were in its past; with the rise of President Nguyen Van Thieu the series of coups that had crippled the nation ceased and ARVN began to solidify and rebuild its strength. However, instead of focusing on helping ARVN come of age, and on the elements of counterinsurgency that could cripple the Viet Cong, US forces mainly concentrated on winning the big unit war, essentially setting ARVN aside in an attempt to win the war for them. While capable of producing spectacular military victories, this strategy did little to create an ARVN that was capable of surviving after America’s eventual withdrawal and did little to buttress the overall strength and durability of the South Vietnamese state. As US forces in South Vietnam grew in numbers and strength, the NVA and VC countered the enemy by bringing more supplies down the Ho Chi Minh Trail and by preparing potential battlefields across South Vietnam with mines, bunker complexes and networks of tunnels. It was not until the fall of 1966 and the onset of Operation Attleboro that US forces made a bid to destroy communist strength in South Vietnam through a series of search and destroy missions into Viet Cong-controlled territory. During October some 22,000 allied forces, including elements of the 1st Division, the 25th Division, the 173rd Airborne, and ARVN swept into War Zone C in Tay Ninh Province near the border with Cambodia. The Viet Cong had many base areas near Saigon that threatened the capital, including War Zone C, the Iron Triangle, and War Zone D. Of these base areas, War Zone C was seen as a particular threat because intelligence indicated that it housed the entire VC 9th Division, and it was only 40 miles north of Saigon.

Although the month-long operation saw several pitched battles US and ARVN forces never succeeded in locking the 9th VC Division into combat. Using its tactical initiative the VC fought, often on carefully prepared battlefields, until its losses reached an unacceptable level and then broke off the engagement and fled across the Cambodian border to its safe havens. During Operation Attleboro US forces killed some 1,100 VC while suffering under 100 fatal casualties. In addition US forces wrecked several VC staging areas and drove the VC into Cambodia. To Westmoreland an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Contents

- INTRODUCTION

- BACKGROUND TO WAR

- WARRING SIDES

- OUTBREAK

- THE FIGHTING

- THE WORLD AROUND WAR

- HOW THE WAR ENDED

- CONCLUSION AND CONSEQUENCES

- CHRONOLOGY

- FURTHER READING

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Vietnam War by Andrew Wiest in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.