![]()

CHARLES BALL

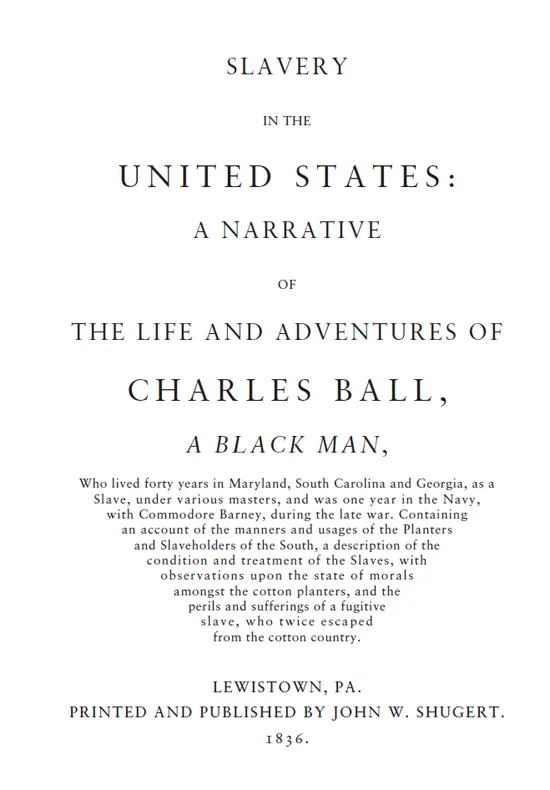

CHARLES BALL (c. 1781–?) was the pseudonym of an anonymous slave who collaborated with Isaac Fisher, a prominent attorney of Lewistown, Pennsylvania, to produce the longest and most detailed slave narrative of the antebellum period.1 No other source more fully describes plantation life from the slave’s point of view; indeed, the book rivals Frederick Law Olmsted’s A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States as one of the best antebellum portraits of the region. Ball possessed a prodigious memory and seems to have recalled almost every meal he ate and every plant or animal he came into contact with. This profusion of detail rarely bogs down his narrative, however, which reads less like an exposition of its title, Slavery in the United States, than an exceptionally well written adventure novel. It includes alligators, snakes, a panther, and, through the eyes of a fellow slave, an African lion; no less than four hair-raising escapes and as many kidnapping attempts; military action in the War of 1812; and an unusual and chilling tale—remarkable for its evenhanded sobriety—of black-on-white crime and its consequences. A surprising twist at the end casts a shadow on all that has come before.

The book has had a long and complex history. In 183 5, prepublication advertisements boasted that the book would expose “the actual condition of the slaves, moral as well as physical, mental as well as corporeal, with greater certainty, and with more accuracy of detail than could be obtained by many years of travel”; and continued, “To those who take delight in lonely and desperate undertakings, pursued with patient and unflinching courage, we recommend the flight and journey from Georgia to Maryland, which exhibits the curious spectacle of a man wandering six months in the United States without speaking to a human creature.”2 The narrative was eagerly anticipated, and, when published in 1836, it met with immediate success; in large part it set the mold for subsequent slave narratives.

Its popularity notwithstanding, the narrative’s veracity was challenged. Even favorable reviewers could not help but notice the lack of documentary evidence. The Quarterly Anti-Slavery Magazine wrote:

Whether the narrative, . . . is real or fictitious, we think its reader will not retain, through many pages, a doubt of the perfect accuracy of its picture of slavery. . . . We are led to this remark, not because we feel ourselves at liberty to doubt the genuineness and reality of the whole, but because the book itself does not answer a number of preliminary questions which the public will not fail to ask. . . .

It is due to the writer to say, and perhaps a higher compliment could not be paid him, that he has accomplished his very important and difficult object, in a manner that would have done credit to the author of Robinson Crusoe. He has traced his hero through all the vicissitudes of slavery, with a minuteness of detail that is truly astonishing, while at the same time the interest of his narrative is ever fresh and growing. The book is not merely readable. It has charm and potency about it. It is one of those books which always draws the reader on by the irresistible magnetism of the next paragraph to the unwelcome appearance of “The end.” . . .

Believing, as we have privately good reason to do, that this book contains, in the language of a faithful interpreter, a true narrative which has fallen from the lips of a veritable fugitive, we have only to regret that there is not an appendix of some sort, containing some documentary evidence to that effect.3

A few months after the book’s publication, another narrative entitled The Slave; or, Memoirs of Archy Moore was published anonymously in Boston, purporting to be the autobiography of a Virginia slave. When it became known that the latter was a novel written by the abolitionist Richard Hildreth, Southern sympathizers lumped both books together and condemned them as fiction.4

This did not prevent the publication of further editions of Ball’s narrative, totaling at least nine in the United States, two in England, and one in Germany. The 1837 (second U.S.) edition included a testimonial signed by two of Lewis-town’s most prominent citizens, certifying that they “know the black man whose narrative is given in this book, and have heard him relate the principal matters contained in the book concerning himself, long before the book was published”; but its introduction also included this disclaimer: “How far this personal narrative is true is a question which each reader must, of course, decide for himself.”5 The 1858 edition was, in the words of John Herbert Nelson, “condensed slightly, bound in a fiery red cover, with great wavering gilt letters staring out at the reader, and handed out to an eager public under the astonishing [and completely inaccurate] title, Fifty Years in Chains”;6 and Marion Starling wrote in 1946, “more copies are to be found of [the 1859 edition of Fifty Years in Chains] than are to be found of any other edition of this slave narrative, or any other slave narrative, in the libraries throughout this country.”7 In sum, Charles Ball’s narrative probably rivaled in popularity those of Olaudah Equiano, Nat Turner, Frederick Douglass, Josiah Henson, and Solomon Northup.

But the accuracy of Ball’s narrative continued to be questioned. One of the most zealous attempts to discredit it was published in the Southern Quarterly Review in January 1853. Vernon Loggins, in his 1931 The Negro Author, wrote “the book has a notorious reputation as a work of deception.” In 1977 John W. Blassingame refuted the 1853 article at length, and, in doing so, substantiated many details of the narrative. But as recently as 1989 Blyden Jackson, in A History of Afro-American Literature, repeated Loggins’s unsubstantiated claim that Charles Ball and Archy Moore were equally fictitious, ignoring Blassingame’s research.8

The presentation of Ball’s story by his amanuensis certainly hasn’t helped its acceptance by historians and literary scholars. Fisher’s preface makes explicit the practices of most of the amanuenses of slave narrators: he admits to omitting or suppressing Ball’s opinions and sentiments and to excluding his “bitterness of heart.” The publisher’s introduction to the 1837 edition goes further:

Mr. Fisher, (the author) intimates in his preface, what is, indeed, sufficiently obvious from the felicity of his style, that the language of the book is not that of the unlettered slave, whose adventures he records. A similar intimation might with equal propriety have been given, in reference to the various profound and interesting reflections interspersed throughout the work. The author states, in a private communication, that many of the anecdotes in the book illustrative of Southern society, were not obtained from Ball, but from other and creditable sources; he avers, however, that all the facts which relate personally to the fugitive, were received from his own lips.9

Clearly, Fisher transformed Ball’s personal narrative into a wide-ranging exposition of the conditions of the slave, and in the process all but erased Ball’s own voice. However, almost all slave narratives, whether self-penned or dictated, deemphasized the psychology of the narrator in the interest of providing a quasi-documentary account. And the hero of Ball’s narrative, while perhaps lacking the psychological depth of William Grimes, Douglass, or Harriet Jacobs, nonetheless emerges as an unforgettable figure in his own right.

PREFACE.

IN the following pages, the reader will find embodied the principal incidents that have occurred in the life of a slave, in the United States of America. The narrative is taken from the mouth of the adventurer himself; and if the copy does not retain the identical words of the original, the sense and import, at least, are faithfully preserved.

Many of his opinions have been cautiously omitted, or carefully suppressed, as being of no value to the reader; and his sentiments upon the subject of slavery, have not been embodied in this work. The design of the writer, who is no more than the recorder of the facts detailed to him by another, has been to render the narrative as simple, and the style of the story as plain, as the laws of the language would permit. To introduce the reader, as it were, to a view of the cotton fields, and exhibit, not to his imagination, but to his very eyes, the mode of life to which the slaves on the southern plantations must conform, has been the primary object of the compiler.

The book has been written without fear or prejudice, and no opinions have been consulted in its composition. The sole view of the writer has been to make the citizens of the United States acquainted with each other, and to give a faithful portrait of the manners, usages, and customs of the southern people, so far as those manners, usages, and customs have fallen under the observations of a common negro slave, endued by nature with a tolerable portion of intellectual capacity. The more reliance is to be placed upon his relations of those things that he saw in the southern country, when it is recollected that he had been born and brought up in a part of the state of Maryland, in which, of all others, the spirit of the “old aristocracy,” as it has not unaptly been called, retained much of its pristine vigour in his youth; and where he had an early opportunity of seeing many of the most respectable, best educated, and most highly enlightened families of both Maryland and Virginia, a constant succession of kind offices, friendly visits, and family alliances, having at that day united the most distinguished inhabitants of the two sides of the Potomac, in the social relations of one people.

It might naturally be expected, that a man who had passed through so many scenes of adversity, and had suffered so many wrongs at the hands of his fellow-man, would feel much of the bitterness of heart that is engendered by a remembrance of unatoned injuries; but every sentiment of this kind has been carefully excluded from the following pages, in which the reader will find nothing but an unadorned detail of acts, and the impressions those acts produced on the mind of him upon whom they operated.

NARRATIVE.10

CHAPTER I.

THE system of slavery, as practised in the United States, has been, and is now, but little understood by the people who live north of the Potomac and the Ohio; for, although individual cases of extreme cruelty and oppression occasionally occur in Maryland, yet the general treatment of the black people, is far more lenient and mild in that state, than it is farther south. This, I presume, is mainly to be attributed to the vicinity of the free state of Pennsylvania; but, in no small degree, to the influence of the population of the cities of Baltimore and Washington, over the families of the planters of the surrounding counties. For experience has taught me, that both masters and mistresses, who, if not observed by strangers, would treat their slaves with the utmost rigour, are so far operated upon, by a sense of shame or pride, as to provide them tolerably with both food and clothing, when they know their conduct is subject to the observation of persons, whose good opinion they wish to preserve. A large number of the most respectable and wealthy people in both Washington and Baltimore, being altogether opposed to the practice of slavery, hold a constant control over the actions of their friends, the farmers, and thus prevent much misery; but in the south, the case is widely different. There, every man, and every woman too, except prevented by poverty, is a slave-holder; and the entire white population is leagued together by a common bond of the most sordid interest, in the torture and oppression of the poor descendants of Africa. If the negro is wronged, there is no one to whom he can complain—if suffering for want of the coarsest food, he dare not steal—if flogged till the flesh falls from his bones, he must not murmur—and if compelled to perform his daily toil in an iron collar, no expression of resentment must escape his lips.

People of the northern states, who make excursions to the south, visit the principal cities and towns, travel the most frequented highways, or even sojourn for a time at the residences of the large planters, and partake of their hospitality and amusements, know nothing of the condition of the southern slaves. To acquire this knowledge, the traveller must take up his abode for a season, in the lodge of the overseer, pass a summer in the remote cotton fields, or spend a year within view of the rice swamps. By attending for one month, the court which the overseer of a large estate holds every evening in the cotton-gin yard, and witnessing the execution of his decrees, a Turk or a Russian would find the tribunals of his country far outdone.

It seems to be a law of nature, that slavery is equally destructive to the master and the slave; for, whilst it stupifies the latter with fear, and reduces him below the condition of man, it brutalizes the former, by the practice of continual tyranny; and makes him the prey of all the vices which render human nature loathsome.

In the following simple narrative of an unlearned man, I have endeavoured, faithfully and truly, to present to the reader, some of the most material accidents which occurred to myself, in a period of thirty years of slavery in the free Republic of the United States; as well as many circumstances, which I observed in the condition and conduct of other persons during that period.

It has been supposed, by many, that the state of the southern slaves is constantly becoming better; and that the treatment which they receive at the hands of their masters, is progressively milder and more humane; but the contrary of all this is unquestionably the truth; for, under the bad culture which is practised in the south, the land is constantly becoming poorer, and the means of getting food, more and more difficult. So long as the land is new and rich, and produces corn and sweet potatoes abundantly, the black people seldom suffer greatly for food; but, when the ground is all cleared, and planted in rice or cotton, corn and potatoes become scarce; and when corn has to be bought on a cotton plantation, the people must expect to make acquaintance with hunger.

My grandfather was brought from Africa, and sold as a slave in Calvert county, in Maryland,11 about the year 1730. I never understood the name of the ship in which he was imported, nor the name of the planter who bought him on his arrival, but at the time I knew him, he was a slave in a family called Mauel, who resided near Leonardtown. My father was a slave in a family named Hantz, living near the same place. My mother was the slave of a tobacco planter, an old man, who died, according to the best of my recollection, when I was about four years old, leaving his property in such a situation that it became necessary, as I suppose, to sell a part of it to pay his debts. Soon after his death, several of his slaves, and with others myself, were sold at public vendue. My mother had several children, my brothers and sisters, and we were all sold on the same day to different purchasers. Our new master took us away, and I never saw my mother, nor any of my brothers and sisters afterwards. This was, I presume, about the year 1785. I learned subsequently, from my father, that my mother was sold to a Georgia trader, who soon after that carried her away from Maryland. Her other children were sold to slave-dealers from Carolina, and were also taken away, so that I was left alone in Calvert county, with my father, whose owner lived only a few miles from my new master’s residence. At the time I was sold I was quite naked, having never had any clothes in my life; but my new master had brought with him a child’s frock or wrapper, belonging to one of his own children; and after he had purchased me, he dressed me in this garment, took me before him on his horse, and started home; but my poor mother, when she saw me leaving her for the last time, ran after me, took me down from the horse, clasped me in her arms, and wept loudly and bitterly over me. My master seemed to pity her, and endeavoured to soothe her distress by telling her that he would be a good master to me, and that I should not want any thing. She then, still holding me in her arms, walked along the road beside the horse as he moved slowly, and earnestly and imploringly besought my master to buy her and the rest of her children, and not permit them to be carried away by the negro buyers; but whilst thus entreating him to save her and her family, the slave-driver, who had first bought her, came running in pursuit of her with a raw hide in his hand. When he overtook us he told her he was her master now, and ordered her to give that little negro to its owner, and come back with him.

My mother then turned to him and cried, “Oh, master, do not take me from my child!” Without making any reply, he gave her two or three heavy blows on the shoulders with his raw hide, snatched me from her arms, handed me to my master, and seizing her by one arm, dragged her back towards the place of sale. My master then quickened the pace of his horse; and as we advanced, the cries of my poor parent became more and more indistinct—at length they died away in the distance, and I never again heard the voice of my poor mother. Young as I was, the horrors of that day sank deeply into my heart, and even at this time, though half a century has elapsed, the terrors of the scene return with painful vividness upon my memory. Frightened at the sight of the cruelties inflicted upon my poor mother, I forgot my own sorrows at parting from her and clung to my new master, as an angel and a saviour, when compared with the hardened fiend into whose power she had fallen. She had been a kind and good mother to me; had warmed me in her bosom in the cold nights of winter; and had often divided the scanty pittance of food allowed her by her mistress, between my brothers, and sisters, and me, and gone supperless to bed herself. Whatever victuals she could obtain beyond the coarse food, salt fish, and corn-bread, allowed to slaves on the Patuxent and Potomac rivers, she carefully distributed among her children, and treated us with all the tenderness which her own miserable condition would permit. I have no doubt that she was chained and driven to Carolina, and toiled out the residue of a forlorn and famished existence in the rice swamps, or indigo fields of the south.

My father never recovered from the effects of the shock, which this sudden and overwhelming ruin of his family gave him. He had formerly been of a gay social temper, and when he came to see us on a Saturday night, he always brought us some little present, such as the means of a poor slave would allow— apples, melons, sweet potatoes, or, if he could procure nothing else, a little parched corn, which tasted better in our cabin, because he had brought it.

He spent the greater part of the time, which his master permitted him to pass with us, in relating such stories as he had learned from his companions, or in singing the rude songs common amongst the slaves of Maryland and Virginia. After this time I never heard him laugh heartily, or sing a song. He became gloomy and morose in his temper, to all but me; and spent nearly all his leisure time with my grandfather, who claimed kindred with some royal family in Africa, and had been a great warrior in his native country. The master of my father was a hard penurious man, and so exceedingly avaricious, that he scarcely allowed himself the common conveniences of life. A stranger to sensibility, he was incapable of tracing the change in the temper and deportment of my father, to its true cause; but attributed it to a sullen discontent with his condition as a slave, and a desire to abandon his service, and seek his liberty by escaping to some of the free states. To prevent the perpetration of this suspected crime of running away from slavery, the old man resolved to sell ...