![]()

1

“The Child Is Father of the Man”1

Background and Early Life

By the close of the nineteenth century, Captain Oswald Every had retired from a distinguished military career as a decorated officer and veteran of the Crimean War and the Indian Mutiny and had been, for a time, the governor of the British prison in Gibraltar. He expected to settle into a pleasant retirement in the English countryside, but the captain was distracted; his son Edward had long since come of age but remained a constant worry. He had done his best to send Edward to the finest schools in England and Spain. He surely was bright enough and fluent in several languages.2 But all the education seemed of little use. Edward’s lack of progress in business, and his other behaviors, troubled the captain. Drawing on his meager knowledge of him (Edward died in 1928), Tom Every ventures, “I think he was drinking whiskey and chasing women, and that’s what I think he was doing. He was a rowdy, that’s what he was.”3 Family history might have given the captain further cause for worry. Two hundred years before, a distant relative, Henry Every (Avery), had given up legitimate trade and had become a well-known pirate holed up on the island of Madagascar. The “arch-pirate,” as he was known, would later be lionized in the stage production of Charles Johnson’s play The Successful Pirate.4 Henry Every also inspired a fictional tale of piracy in Daniel Defoe’s novel King of the Pyrates in 1719.5 Tom holds the pirate Henry Every in fond regard, thinking himself cut from the same cloth; he even went so far as to name his truck the “Fancy” after the arch-pirate’s ship.

Captain Oswald Every came up with a then-common solution to his problem— soon Edward was on a ship with one thousand dollars in his pocket and two hunting guns in his baggage. The plan was for him to become a gentleman farmer in America, but that’s the last his family ever saw of him. This kind of situation was not uncommon in the 1800s. Mark Twain, writing at this same time, explains:

Whether Edward (Ted) was a “dissipated ne’er-do-well” or not is hard to say; he seems to have been on good behavior in his new home, where he soon traded one of the hand-tooled shotguns for a buggy worth only ten dollars. Tom says, “He was never very good with money or business.” He soon found he could not keep himself in the lifestyle that he was used to in England, and his dreams of a life of estate management and leisure faded away. We next hear of him in Wisconsin, where he met and fell in love with Adeline Smith, a schoolteacher and a dedicated Christian Scientist whose Yankee English family had moved to Wisconsin in the 1870s from Springfield, Massachusetts. Ted and Adeline were married in August 1902 and settled in Brooklyn, Wisconsin. “I never heard of him doing any drinking over here,” recalls Tom. In Brooklyn, he was industrious, working as a butter maker in the Brooklyn Creamery—where after hours he could be found taking baths in the cheese vats—and later as a clerk in the local mercantile, where he could be heard crowing loudly whenever an embarrassed young lady asked for Rooster brand toilet paper. He was a well-liked character around town; he was the only person in the area with an English accent and was, according to Tom, “laid back and would sit on the porch and smoke cigars.”7

The Everys come from an old English family who took their name from their place of origin in France. The older form of the family name is Yvery, or Ivry. They are proud of their Norman origins and claim that their forebearers arrived in England at the time of William the Conqueror in 1066 and settled in the Midlands, where they lived and prospered over the centuries, finding favor with the royal court through the era of the Tudors. The family managed to survive the upheavals of the English civil war and the political intrigues that followed and kept possession of their titles and estates near Egginton, where Tom and his sister Barbara have visited their present-day relatives.

The Every coat of arms contains the Latin motto “Suum Cuique,” which translates as “to each his own.” These days it could be translated as “do your own thing,” a motto that would be lived up to in its fullest in the person of Tom Every.8

Ted and Adeline Every had three sons: Edward Malcolm in 1903, Roderick Desmond in 1904, and Donovan Richmond in 1911. Tom’s dad, Malcolm (Mac), grew up in Brooklyn and early on showed an interest in tinkering. As a boy he had a 1908 one-cylinder car in which he clanged up and down the streets delivering newspapers. He gravitated to Graves Machine Shop, where he spent his spare time fixing his motorcycle or working on his Model T race car in which he sped around town. Mac was a smart and self-conscious young man and did well in school, and when it was time to go off to college he chose the University of Wisconsin at Platteville. He told Tom that he chose Platteville because the dress code was not as tough as the code at the University of Wisconsin in Madison and he didn’t have a lot of money. He made his way through the first two years there attending classes during the day and sleeping in the warm powerhouse, where he had a part-time job watching the boiler gauges, at night.

After two years in Platteville, he transferred to the university in Madison, where he pursued a degree in civil engineering. After graduation, he took a job with the state, where he spent his working life making his way up through the ranks and ending up as the chief of engineering services for the State of Wisconsin. During his career, he was responsible for the layout of state highways.

In 1934 Malcolm married Clarice Doane. The Doanes trace their ancestry right back to the Mayflower. The family advanced in the New World as industrialists and builders. Clarice worked as a secretary in the office of Farmers Mutual Insurance Company when there were only six people in the office; the company would later grow much larger under the name American Family Insurance. In later years, when the children were of school age, she worked as a bank secretary in Brooklyn.

Thomas Owen Every was born in Madison on September 20, 1938, and even as a small child he was a natural-born forager and loved to play near the local bus barn (although this was strictly forbidden) because it was, in his words, “where you could find the really good stuff.” Whether on the Indian trails along the lake or at the dump, a boy could fuel his imagination of the east side, the industrial side, of wartime Madison.

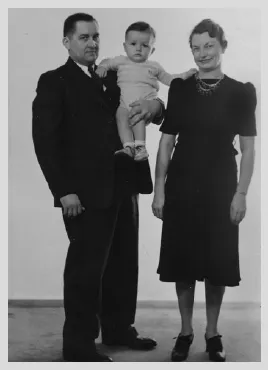

Tom with his parents EVERY COLLECTION

Tom recalls the smell of stale beer from the Union House Tavern owned by his next-door neighbors, the Essers. The tavern served the air force fliers from nearby Truax Field. On weekends he was often invited to come along for a ride in the country in the back of the Essers’ black DeSoto with their daughter Betty Jo.

More than fifty years later Tom would be made uncomfortable by a woman intently looking at him in the sculpture park, so he asked her if there was something that he could do for her. She introduced herself as Betty Jo Esser and reminded him that she was the girl of his first kiss.

Tom was too restless for Lowell School, where he attended through the third grade. He says he didn’t do too well.9 His grandmother Every (a schoolteacher) had a big influence on him. She stayed with the family in her later years and read to Tom all of the classics of children’s literature including Huckleberry Finn and Tom Sawyer. She was set in her ways—Tom recalls her resisting the family when they tried to take her to the hospital when she broke her arm. They did manage, after much wrangling and arguing, to convince her to see a doctor. Tom would, years later, have a similar suspicion of doctors and hospitals.

What Tom really liked was collecting loads of newspapers and hauling them to collection centers in his red Radio Flyer wagon. It was wartime, and the whole country was collecting and recycling strategic materials; it was a patriotic duty to collect materials needed for the war effort. Young and old alike did what they could. As the war came to an end, interest in collecting and recycling waned for most people, but not for Tom. He kept gathering up almost anything that people didn’t want: paper, used toothpaste tubes, scrap metal.

In 1942 Tom’s sister, Barbara, was born. The family continued to live on the east side of Madison until 1946, when they moved to Brooklyn, Wisconsin. They took up residence at 102 Lincoln Street, the former home of grandfather Edward and grandmother Adeline.

Tom in grade school EVERY COLLECTION

The gently rolling hills and flat prairie around Brooklyn stretch out to the horizon in every direction. You can see summer storms gathering in the distance and raining on the fields. Songbirds today make melodies in the green woodlots and fencerows, and Holstein cows graze the green fields as they did years ago. Some of the smaller farms scattered here and there have been joined together to form larger operations, but many old barns and farm homes still stand as they have for a hundred years or more. Brooklyn is typical of the many small Wisconsin villages that grew up to serve the neighboring farms. Although some of the old buildings are gone, and the creamery has long since been torn down, it’s easy to imagine the main street full of life and business. The chug and whistle of the steam trains that Tom loved so much have been replaced by diesel engines; the Chicago and Northwestern tracks are still there, but the trains no longer stop in Brooklyn and the station is gone. If you close your eyes, you can imagine the slap of the screen door on the white frame house at 102 Lincoln and Tom running off on one of his foraging missions.

Tom followed his dad around the family farm (the Doane farm) near Stoughton, where they raised beef cattle and hogs. Tom spent many days there watching his dad, picking up carpentry skills and learning how to use the materials at hand. He has fond memories of those days:

Tom on horseback EVERY COLLECTION

One day in 1950 his dad got tickets to the fights at the University of Wisconsin Field House. There, from a ringside seat, Tom first saw Alex Jordan. By this time, Jordan was really too old for the sport, but he boxed that day as a heavyweight. Alex Jordan would later play a role in Tom’s life, and he would contend with Alex, although not in the boxing ring; for now, Tom was just a boy out for the day with his dad. Tom remembers his time with his father with nostalgia, saying, “I think it was a wonderful bond.”

Tom began to bring home everything. He says that his saving, this “disease of all,” as he calls it, came from his first experiences on the east side of Madison.10 Soon people in and around Brooklyn knew just whom to call when they wanted to get rid of their unwanted materials. Tom’s mother would take the message over the phone and he would go pick up whatever they gave him. His parents really didn’t know what to think.

The mess and debris around 102 Lincoln Street got to be too much, so to keep peace Tom found a place along the railroad tracks to stash his stuff. Vince Martin was the stationmaster at the Brooklyn railroad depot and soon befriended Tom. This was at the end of the age of steam trains; in those days, all of the little towns depended on the railroad to bring goods and to take their products to market. Tom recalls, “I was always there when the old steam trains came in. So I felt the spirit of the old steam trains and the old depot. It had two rooms and a big stove and a telegraph. Vince Martin was an old bachelor and he did everything an o...