By “Theravada”, we refer to those traditions who today self-identify as “Theravada Buddhist”—as a particular type of Buddhism. We are well aware that the term has been used in different ways through history, particularly as a marker of a particular monastic lineage (among many early Buddhist schools and lineages). “Theravada Buddhism” as used today is thus a neologism denoting a variety of historically connected traditions. Theravada Buddhism has traditionally held a stronghold in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and parts of Vietnam. This volume is confined to the Theravada majority states that have experienced the highest levels of Buddhist–Muslim contention in recent years, namely Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thailand.

End AbstractIs there an Islamic campaign to take over Sri Lanka and Myanmar? Did Muslims drive the Buddhists out of India? Have Buddhists and Muslims always had problems trying to live together? In recent years, these questions have emerged in both popular parlance and the news. Even though Muslims represent numerically small minorities in Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thailand, the Buddhist majority in these countries have expressed concern that a Muslim population increase will drive out the Buddhists. When Buddhists voice these concerns, they often point to a historical legacy of Islamification, carried out by various Muslim rulers that purportedly drove out the Buddhists from India. Even though scholars have questioned this interpretation of South Asian history the narrative not only persists,1 but seems to take on new significance among Buddhist activist groups in the region.

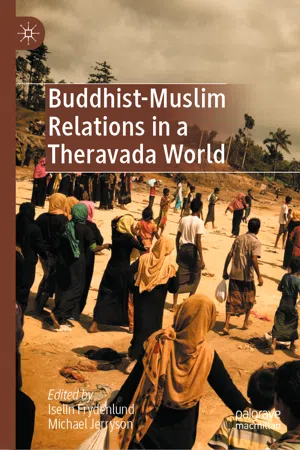

The current public concern over Muslim–Buddhist relations in South and Southeast Asia take place in the wake of massive violence against Muslim minority communities in Buddhist majority states in the region. During these years, scholars and journalists raised questions about Buddhist–Muslim relations in the wake of anti-Muslim violence.2 Certainly, threads of Buddhist anti-Muslim sentiments can be traced historically, but the scale of attacks on Muslim minorities is historically unprecedented. One example of this is the 2017 exodus of over 670,000 people from the Rohingya community in Myanmar. The Rohingya are a small Bengali-speaking Muslim community comprised of roughly 1.1 million people, who live on both sides of the Bangladeshi-Burmese border. The human rights violations against the Rohingya will stand in world history as a grotesque reminder of how adherents of a religion—Buddhism—justified ethnic cleansing and horrific acts of violence against an ethnic and religious minority community.

The recent pattern of religiously fueled conflicts in Sri Lanka, Myanmar and southern Thailand suggest that Buddhists and Muslims have irreconcilable differences. However, history shows that Muslims and Buddhists have lived together for centuries without violence, or even major instances of contestation. In fact, Muslim communities have a long history in Buddhist majority states, representing ethnically, culturally and religiously complex—albeit small—populations.

Yet, Buddhist–Muslim relations in a Theravada Buddhist context have received surprisingly little academic attention. Surely, due to the prolonged military involvement, imposed martial law and the rise of Malay Muslim separatist movements over the last 14 years, Buddhist–Muslim relations in southern Thailand have received scholarly attention.3 In addition to examining areas of conflict between Muslims and Buddhists, ethnographic work in this region has paid attention to coexistence and notions of civility in mixed Muslim–Buddhist villages in southern Thailand.4 Furthermore, just beyond the borders of Thailand, there have been very informative ethnographic works on Buddhist–Muslim interactions in Malaysia.5 Recently, and largely in response to the massive violence against Muslim minorities since 2012, scholars have started to address the research lacuna of Muslim–Buddhist relations (or even research on Muslim communities in their own right) in Myanmar6 and in Sri Lanka.7 These studies offer powerful insights into contemporary Muslim–Buddhist formations in particular regions. Yet, it would be fair to say that the academic community is only beginning to unpack the more than a thousand years of Muslim–Buddhist relations in Asia, and that the academic study of Buddhist–Muslim encounters in South and Southeast Asia is in its infancy. While previous research offers specific glimpses into instances of Muslim–Buddhist interaction in particular contexts, few studies so far have been devoted to Muslim–Buddhist relations from a comparative regional perspective or on transnational webs across states.

Aims of This Volume

We conceived this edited volume in a response to this need. The aim of this book is to unravel the various dimensions of Muslim–Buddhist relations in Buddhist majority states in South and Southeast Asia. Collectively, the chapters provide an informed and scholarly response to contemporary Buddhist–Muslim interaction in Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thailand. What brings the contributions of this volume together is that they take as their starting point Buddhist–Muslim encounters within the framework of Buddhist majority states. We have also included a chapter on Bangladesh as this case very specifically illustrates two important points of this book, namely the importance of shifting state formations for Buddhist–Muslim relations and the fluid nature of religious and national identities.

By bringing together experts on Myanmar, Sri Lanka, Thailand and Bangladesh, this volume seeks to bring country-specific knowledge into a broader discussion about Muslim–Buddhist interactions across the region. This is important, we believe, as religious identities are shaped differently in majority and minority contexts. Buddhist minority nationalism in Muslim majority Bangladesh takes on different qualities than majority Buddhist nationalisms in Buddhist majority states. Furthermore, majority–minority relations are not confined to state borders: Muslims are in majority in Bangladesh, but a minority in Thailand. Muslims in Bangladesh sympathize with the sufferings of the Rohingyas; simultaneously, Buddhist monks throughout the region focus on minority Buddhists in Muslim majority societies like Bangladesh, southern Thailand and Malaysia. Facilitated by social media, migration and new forms of political communities such as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), there is a new regional concern about religious minorities and majorities across the region.

Thus, the aim of this volume is three-fold. First, by bringing together detailed knowledge on Muslim–Buddhist relations in three majority Buddhist states we seek to provide a work that allows the identification of similarities and differences embedded in Buddhist–Muslim relations in nation-states that retain a preference for Buddhism. Second, by bringing in an explicit regional perspective in the study of Buddhist–Muslim relations we seek to identify regional and global factors that inform relations at local and state levels. Third, we employ analytical tools that are useful for further exploration into the study of Muslim–Buddhist relations. Here we wish to contribute to a broader understanding of religious encounters, both in terms of mix and exchange but also in terms of resistance, purification and differentiation. Also, we want to be clear that this volume is not concerned with Buddhist or Islamic normative sources for peace-building in the region,8 but rather with contributing with fresh perspectives and nuanced understandings of complex interreligious dynamics.

The Historical Legacy of Muslim–Buddhist Relations

What, then, do we know about Buddhist–Muslim relations in the past? In the following, we will provide an overview over major historical developments that have shaped Buddhist–Muslim relations and that will place this volume in its broader historical context.

In his comprehensive historical account of the encounter between Islam and Buddhism on the Silk Road, Johan Elverskog shows the rich and complex history of Buddhist–Muslim encounters from Iran to China. These first meetings took place in the Sindh, Afghan and Iranian areas, as a result of Arab trade in the eighth century CE. Importantly, conversion of non-believers was not the primary aim of these expeditions as at this early stage only Arabs could become Muslims.9 Moreover, most of northwest India was brought under Muslim control not by force, but through treaty,10 and Buddhists were classified in relation to Zoroastrianism and thus given dhimmi status and subsequent protection and privilege within the emerging Muslim polities.11 Important sources for such early instances of Buddhist–Muslim contact are texts produced along the Silk Road; Islamic authors produced studies on Buddhist thought and practices,12 and the North Indian Buddhist text the Kalacakra Tantra (transmitted to Tibet in 1027) offers us one of the earliest Buddhist interpretations of Muslim beliefs and practices, including condemnation of circumcision and animal sacrifice.13 Elverskog’s work on the multiple Buddhist–Muslim encounters along the Silk Road shows in important ways the historical fluctuations of Buddhist–Muslim interaction and how they relate to wider political contexts and imperial policies. Such a perspective allows for a fine-grained analysis of contradictions and change, showing that imperial policies might entail an interplay between pluralistic approaches to religious diversity on the one hand and brutal suppression on the other.

Muslim–Buddhist Relations in Pre-colonial South and Southeast Asia

At the dawn of European colonialism, Southeast Asia encompassed some of the most diverse cultures in early modern history, marked by circulation of people, commodities, ideas and beliefs along the key trading routes, from the Eastern edge of the Mughal empire to the southern Chinese border.14 Muslim rulers expanding into Asia did not reach the Buddhist polities of Burma, Siam or Lanka. As such, Muslim communities in these regions are not the heritage of Arab, Turkish or Persian expansionism, like in parts of the Indian subcontinent. Rather, through trade networks, Muslim communities formed an integral part of culturally diverse states. In the early modern period, Muslims across the region comprised of a great variety of ethnic and linguistic groups, including Persian Shias, Cham refugees from Cambodia, and Javanese, Chinese and Arab traders. Muslim trading communities settled in cosmopolitan port cities, and from there to the inlands.

The manner in which different state formations and ideologies across the region dealt with cultural difference obviously varied through time and space. Pre-colonial state formations in the region were very different from the modern states of Sri Lanka, Myanmar and Thaila...