1 Samuelson the Scientist

Paul A. Samuelson (1915–2009) was a scientist. In his author’s preface to volume 5 of his Collected Papers, he alibies his lack of progress on a commissioned study of the growth, during his lifetime, of economic science with the argument: “How can I write about science while busily engaged in doing science?” (Samuelson 1986: xi; italics in original).

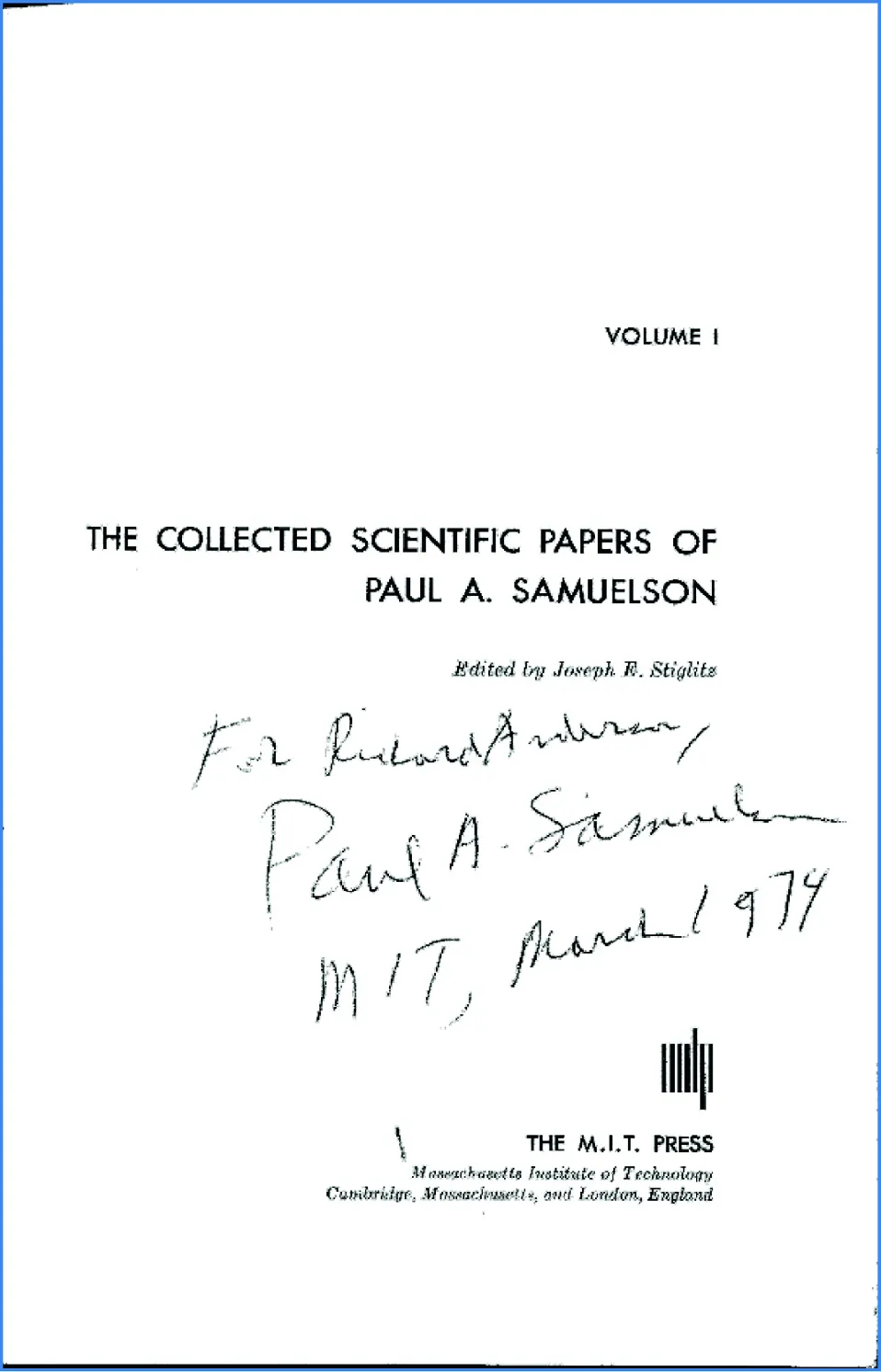

Samuelson’s dedication of a copy of volume 1 of his Collected Scientific Papers to the author, on the occasion of taking Samuelson’s second-year welfare economics class.

Scientists build models that suggest hypotheses (or assertions) that can be judged against data. No idle observer, Samuelson did not speculate about economic behavior by examining charts of data. Nor was he an iconoclast who rejected all evidence contrary to a preconceived stance. Rather, his models built on the foundation of economic analysis: that economic agents seek to maximize an (often dynamic) objective function subject to (often intertemporal) constraints. Samuelson’s Collected Scientific Papers comprise seven substantial volumes from The MIT Press. Beyond scientific papers, the volumes include essays written for the popular press that some might regard as non-scientific. In the author’s preface to volume 5, Samuelson thanks Kate Crowley for saving “from my rejection various popularizations, arguing persuasively that historians of our times will need to know how scholars reacted from year to year to the important problems of the age” (ibid.). Janice Murray, his longtime assistant at MIT, has done the same in volumes 6 and 7.

Samuelson’s efforts touched all subject areas within economics and finance: pure theory (demand theory for households and firms , welfare economics, growth theory, game theory); history of economic thought, including biographical and autobiographical writings; international economics; stochastic process theory , particularly with respect to finance and investing; mathematical biology ; and essays on current economic policy. His science was both deep and broad, mathematically precise and yet focused on real-world economic problems.

Although it has been suggested that Samuelson’s work in economics reflected little more than an application of physical-science mathematics (a cross-fertilization that has built some distinguished careers), Samuelson himself argued firmly that this was not true: his interest in economics was all-consuming from his first days at Chicago. Samuelson found economics in 1932 “poised to become mathematical” (Samuelson 1991 [2011]: 937). He added: “The generation of my teachers found mathematics a sore cross to bear. In their presidential addresses, they inveighed against it as pretentious and sterile, seeking comfort by quoting the views of Marshall, Pigou and Keynes on the triviality of mathematical economics. But that wolf at their door just would not go away. Funeral by funeral they lost their battle” (ibid.: 939).

Samuelson noted several times in his papers a debt to Edwin Bidwell Wilson, an extraordinary mathematician, the only graduate student of Yale’s William Gibbs (the founder of the field of chemical thermodynamics), a professor at MIT from 1907 to 1922, and at Harvard’s School of Public Health during Samuelson’s time at Harvard. Samuelson stated that: “I was perhaps his only disciple: in 1935–1936, Abram Bergson, Sidney Alexander, Joseph Schumpeter and I were the only students in his mathematical economics seminar” (Samuelson 1998: 1376). He added that Wilson “had great contempt for social scientists who aped the more exact sciences in a parrot-like way. I was vaccinated early to understand that economics and physics could share the same formal mathematical theorems…while still not resting on the same empirical foundations and certainties” (ibid.). Wilson, later in 1940, strongly encouraged Samuelson to accept MIT’s offer as an assistant professor rather than remain at Harvard as an instructor. Yet, Samuelson was eclectic: He noted that for intellectual recreation, he often sought to solve problems in thermodynamics, and he kept his eyes open for practical mathematical tools that might be applied in economic theory. Beyond these, he preferred tennis and reading mystery novels as recreation, not mathematical puzzles.

2 Samuelson the Autobiographer

Samuelson remarked that he did not “shirk” in his writings from talking about his professional development. His personal reflections are “peppered” through many of his papers, in addition to several autobiographical papers: 1968’s Presidential Address before the World Congress of the International Economic Association, “The Way of an Economist”; 1972’s “Economics in a Golden Age: A Personal Memoir”; 1983’s “My Lifetime Philosophy”; and 1986’s “Economics in My Time.” Kate Crowley, in volume 5 of the Collected Scientific Papers, devotes part VII to Samuelson’s autobiographical writings. Janice Murray, in volume 7, devotes part X—some 250 pages—to similar writings. In these, we learn that Samuelson was born in Gary, Indiana; that between the age of 17 months and 5 1/2 years, he was sent to live half-time with relatives on a farm near Valparaiso, Indiana, that lacked both electricity and indoor plumbing; that his father was a Polish Jewish pharmacist who prospered during the First World War; that his family moved to Miami Beach during the mid-1920s Florida land boom and bust, making a small fortune in real estate “by starting with a large one”; that when the family returned to Chicago he attended Hyde Park High School; and that he was a strong student, graduating at age 16. We also learn how he met and romanced his wife, and we view the multiple intersecting forces (Wilson’s push, Harold Freeman’s pull, and subtle anti-Semitism at Harvard and elsewhere in academia) that affected his 1940 decision to accept a position at MIT. Samuelson withholds few details .

We also learn of the Great Depression’s lifelong impact on his macroeconomics—he noted that as an undergraduate, he spent four pleasant summers on Chicago’s Lake Michigan beaches because there were no jobs to be found (he notes that he seldom used his time applying for jobs since the failure of hundreds of his classmates to obtain jobs revealed their scarcity). From this experience, short-term inflexible wages and prices became a part of his analysis, leading to an ingrained belief in activist government business cycle macroeconomic policy , both fiscal and monetary. Samuelson noted that at first, he rejected Keynes’s General Theory as ad hoc and inconsistent with economic theory—but on subsequent readings, he came to accept much of Keynes’s analysis. Throughout his career, he remained a self-described Keynesian.

Samuelson noted several times in his autobiographical writings that he came to economics at 8 a.m. 2 January 1932 when, at the age of 16 and not yet officially graduated from Hyde Park High School, he became a commuter student at the University of Chicago. He states that no great thought went into selecting Chicago: It was close by and, in those days, most students went to nearby schools. By chance, Chicago, he argues, had the nation’s best economics department and was the ideal place to learn classical economics. At the end of his undergraduate studies in 1935, he received a Social Science Research Council scholarship that required he undertake graduate studies at a different school. He chose Harvard. Superbly confident, he did not apply to do graduate study but simply showed up and presented himself. Samuelson noted that he developed at Chicago strong backgrounds in both economics and the physical sciences; at Harvard, he found his economics background superior to almost all classmates, allowing him to attack advanced courses sooner than his contemporaries.

Samuelson emphasized in a 1972 memoir that professional success is complicated. His success depended on having had great teachers, great colleagues, great collaborators, great students, great initial talent including analytical ability, good luck—plus a great deal of hard work (Samuelson 1972: 155). MIT graduate students, including this author, recall many an evening, holiday, and weekend when Samuelson’s was the sole occupied faculty office in the third-floor economics corridor of building E52 (doesn’t he ever not work?).

Samuelson’s memoirs reward the careful reader with insights. Limited space precludes my saying more.

3 Samuelson and This Volume

Samuelson said that he had his fingers in every part of the economics pie, and the papers in this volume reflect his broad interests. If Samuelson had a methodology, it was that economics was about optimization subject to constraints; if Samuelson had an ideology, it was that markets should be allowed to solve most economic problems subject to an ethically acceptable set of initial conditions (including income and wealth distribution ) and an absence of externalities and monopoly power (Samuelson 1991). In the event, the methodology, as exercised in mathematical models, was easier than the ideology, often exercised in his nontechnical writings. His Collected Scientific Papers contain both, especially the posthumous volumes 6 and 7.

There seems little value here in a detailed summary of this volume’s 21 papers because readers of this introduction likely have those papers in hand. Hence, only a brief survey follows.

With a broad brush, the economics pie and Samuelson’s contributions might be sliced into three pieces: methodology, especially the role of mathematical models that necessarily omit features of the actual world to illustrate specific important relationships; microeconomics and finance, including the pure theory of consumer choice , Samuelson’s first area of applying mathematics to economics; and macroeconomics, including international trade and development .

Ours is not the first volume seeking to appraise the Samuelson revolution in economic science. Superb collections are Brown and Solow (1983), a Festschrift by MIT friends and colleagues on the occasion of Samuelson’s 65th birthday, and Szenberg et al. (2006), a Festschrift on the occasion of his 90th birthday. In a 2012 survey article, Princeton’s Avinash Dixit summarized the challenge for those who follow:

These chapters [in these two volumes] provide excellent and thorough statements of Samuelson’s research and its impact. That makes my job simultaneously easy and difficult. I need not give much detailed exposition or explanation of his work, but even brief sketches may be too repetitive. (Dixit 2012: 2)

Dixit added:

Many principles of economics were hidden in obscure verbiage of previous generations; he reformulated and extended them with crystal clarity in the language of mathematics. The citation for his Nobel Prize reads, ‘for the scientific work through which he has developed static and dynamic economic theory and actively contributed to raising the level of analysis in economic science.’ He left his mark on most fields of economics. He launched new fields and revolutionized stagnant fields. And he spanned this amazing breadth without the least sacrifice of depth in any of his endeavors.In every one of the eight decades since the 1930s, he made fundamental contributions that enlightened, corrected, and challenged the rest of us. His collected works in seven massive volumes comprise 597 items. He firmly believed that it was a scientist’s duty to communicate his knowledge to the profession; that it was ‘a sin not to publish’… He molded several generations of graduate students at MIT and researchers throughout the profession. His introductory textbook guided the thinking of millions throughout the world; it was instrumental in spreading the Keynesian revolution; and it was a model that all subsequent textbooks followed. Hi...