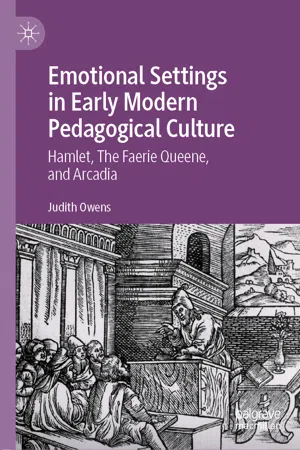

A sixteenth-century English woodcut included in John Day’s 1563 Whole Book of Psalms depicts a scene that played out daily in countless sixteenth-century English households: familial instruction in moral and spiritual matters.1 On one side of the room is a father, portrayed in what Lena Cowen Orlin has described as “commanding solitude”; on the other side are a visibly expectant mother and several children, grouped together.2 At first glance, we might be inclined to see, with Orlin, a clear-cut picture of patriarchy in action. The father has an imposing, weighty presence: he is well-dressed and self-assured in bearing; angled slightly forwards and towards the viewer, he sits securely on a high-backed, cushioned chair; his right leg, draped with his cloak, is bent at an acute angle, the heel of the right foot raised and pressing against the leg of the chair or perhaps hooked under a rung; his left leg, clad in hose that shows off a well-formed calf muscle, is thrust forwards at an angle of about 120 degrees, the left foot planted firmly on the floor. Instructing without the aid of any book, he touches the thumb of his right hand with his left index finger as he enumerates the points of the lesson. (Today, someone might reproach him with mansplaining and manspreading.) His wife and children are grouped opposite him—“clustered together,” to use Orlin’s apt term—and, as a group, pushed just perceptibly back from the foreground. The mother and two of the children appear to be seated on a bench, with the rest of the children standing behind. One child has reached up to tuck his hand into the crook of his mother’s arm; all the children are close to her, within easy touching distance. Although the children must be of varying ages, they are positioned in such a way, some seated, some standing, that the tops of all their heads are just a few inches below the mother’s shoulders. The wife and children—as a unit—have gathered together in front of the head of the household for the daily lesson, demonstrating the deference that was due to the father in this highly patriarchal century, and exuding the cheerful quietness that moralists of domestic life said, time and again, should characterize a family ruled properly by a husband and father.3

The scene nevertheless manages to convey a degree of familial affection and informality that at least qualifies if it does not override the deference that strikes the keynote for some viewers—and supports for them the assumption (long entrenched) that patriarchal structures of authority in early modern England were fixed and firm. Of the two children flanking the mother, one carries a toy, a hobby-horse; another, the one holding a book (of psalms?) and looking to the side, past his mother, to the younger boy, seems to be more interested in his sibling than in his father’s enumeration of points. And while the father just might be frowning ever so slightly in the direction of the wayward child, his reprimand seems quite muted—and, more to the point, unheeded, by the child and by the mother, who does not seem anxious in the least about the conduct of her children in the presence of the patriarch. Of the children—two, just possibly three—who are standing behind the mother, at least one of them is not attending very closely to the father’s instruction. The mother herself does seem to be attuned dutifully to what her husband is saying (or, more likely, reiterating, since such instruction was so often part of the familial routine); but she also appears to be a little preoccupied with her pregnancy. Her hands, crossed in front of her, rest on the noticeable curve of her abdomen; the fingers of her right hand are plucking at the fabric of her skirt. She is seated in the midst of her children and her billowing skirts almost seem to form a nest. While the occasion is one of patriarchal instruction, we thus sense considerable warmth and ease of feeling. There is no question about the father’s holding a position of authority in this instructional setting, but that authority is contextualized, not as sternly remote and unilateral, but as tempered by emotional dynamics, as well as directed towards occasionally inattentive individuals who are distracted from the lesson—and with impunity—by their own interests and preoccupations. To attend to the nuances of emotion and mood depicted in this illustration is to see that patriarchal authority could be experienced as flexible.

My reading of this illustration reflects the primary questions underlying Emotional Settings: How does the picture we might have formed from preconceptions—of an institution, a social practice, a pedagogical regimen, a set of relationships, or a familiar, even canonical, work of literature—change when we focus our attention on emotional dynamics? What comes newly or more sharply into view? What recedes? As the sheer volume of recent scholarship on affect and emotions attests, these questions are hardly new. My book breaks new ground, however, in terms of the works, literary and non-literary, that I bring together for the first time; in terms of how I construe the pedagogical context within which I then study seminal works by Shakespeare, Spenser, and Sidney; in terms of new readings, literary and non-literary; and in terms of my methodology.

In chapters on the humanist schoolroom , filial relationships, The New Arcadia and The Defence of Poesy, The Faerie Queene, and Hamlet, I aim to furnish new ways to think about two closely interrelated concerns: shaping boys into civil subjects of the commonwealth and fashioning heroic agency and selfhood in literature. In these aims, I am guided by a host of questions in addition to the ones just posed (not all of them pertinent to each and every chapter). When is it as important to think about what instruction and learning feel like in early modern pedagogical settings, actual or literary, as it is to think about what pupils learn in those settings? What role does emotion play in shaping the moral learning so fundamental both to early-modern instructional regimens and to literature with civic aims? What happens when the emotional and moral imperatives of humanist grammar-school education conflict with those of families? How does literature register such affective tremors? In what ways do the technologies of learning employed in the home or the classroom shape affective and moral responses? How does literature engage with the habits of mind and feeling cultivated by such technologies as the commonplace book or the formation of maxims? Does the affective charge of an instructional setting—a schoolroom, a family—reinforce or undermine structures of authority? How can an emotional response challenge the patriarchal authority on which both households and schools rested? How does literature record the emotional fallout from such a challenge? What kind of mediating role do mothers play within a pedagogical culture built on patriarchal authority? How can we gauge affective charge and emotional responses in documents related to the pedagogies of early-modern schoolrooms and families? How do we even measure emotional dynamics in the texts by Spenser or Sidney or Shakespeare? My answer to the last two questions is that we can do so most effectively by paying close attention to language: syntax, sentence structure, turns of phrase, and metaphors are exceptionally responsive to affective pressures.

* * *

These interrelated questions and aims are at the heart of Emotional Settings in Early Modern Pedagogical Culture: Hamlet, The Faerie Queene, and Arcadia. They are not quite the questions that I set out to address with this book. My initial interest was sparked by Hamlet’s vow to obey his dead father’s command to avenge his death, especially by Hamlet’s assuming immediately that he would have to wipe from his memory all that he’d been taught in his humanist schooling in order to execute his father’s will.4 When I found a comparable knot of conflicting imperatives in Spenser’s The Faerie Queene, in the Ruddymane episode of Book II, where the “vertuous lore” foundational in humanist education aligns imperfectly with the “gentle noriture” of home in the promotion of filial revenge, I was struck by the fact that two such vastly different works (and writers) identified a potential for conflict between familial imperatives and humanist pedagogy.5 This tension seemed worth investigating since not only are household and school two of the most important instructional settings of the sixteenth century in England but the instructional regimens proper to each are often regarded as dovetailing seamlessly. Vocabulary points to the shared pedagogical aims of families and schoolrooms. Spenser’s phrase, “vertuous lore,” directs us towards what is arguably the most significant aim of the humanist educational programme: the inculcation of virtue, especially civic virtue.6 Both the curricula and the instructional practices of grammar schools were geared towards turning boys into the men who would serve the commonwealth in the capacities needed to promote the emerging socio-economic, political, and religious agendas that superseded what Mervyn James identified as “lineage society.”7 From domestic conduct books, sermons, homilies, and family correspondence, we know that parents, too, at all levels of society, were enjoined to instil virtue, including civic virtue, in children (especially sons), a mandate that grew more urgent through the course of the sixteenth century.8 Moreover, both household and school, at least in theory, operate under the banner of patriarchal authority, a model of governance generating the frequently-invoked analogy between fathers and schoolmasters.9

With the fraught moments from Hamlet and The Faerie Queene in mind, I planned to explore further the ways in which early modern literature used the deeply-felt analogies that linked family and school (and often the state) in shared aims and structures of authority as sixteenth-century civic society emerged from old feudal orders. To what extent, I wondered, were these analogies able to foreground complementarity among configurations of authority only by masking contradictions, contradictions that surface in imaginative literature? To what extent did these analogies reflect lived experience? I wondered how secure these analogies could be when two ...