The traditional approach to the analysis of nominating politics in the United States, and a very long tradition at that, was to focus on the specifics of individual contests. These were judged to be consequential in their own right. After all, they were what gave us our presidents. Beyond that, individual contests could also be studied comparatively, usually with the most recent version interpreted by comparison to various predecessors. A second, more contemporary approach sought to move toward generalization while still retaining the specifics of contemporary contests. Though implicitly, this remained an approach valorizing individual contenders, distinctive strategies, and the interactions of both with institutional strictures and campaign practices.1

In the 1980s, a third approach to understanding the politics of presidential nomination began to appear, likewise comparative as among individual contests but seeking to work at what we are calling the opposite end of the causal funnel. To that end, it sought to generalize either across a greater temporal span or with a greater focus on theoretical explanations or, of course, both. By itself, a longer time span would contribute to explanations that were more fundamental and less idiosyncratic. By definition, an attempt to isolate a small set of shaping influences and apply them to multiple contests would contribute to those same ends. This approach did not yet dub itself a separate school of thought, and it certainly did not go on to use its results to organize and “discipline” the products of previous research, but it was incipiently foundational for any effort to do precisely that.

In a sense, then, everything in this chapter is an attempt to take that next step, searching for evidence of a long-running bandwagon effect in presidential nominating politics, coupling this with some strong theorizing about how this bandwagon might have developed and why it rolled so consistently across time, and using the result to gather, discipline, and reorganize an established way of thinking about presidential nominations. To that end, this chapter needs to reach back and resurrect that first set of initial (and critical) contributions toward a different way of thinking about nominating politics. It needs to drive their insights as far across American history as the course of practical politics will allow. And having teased out a long-running commonality to the politics of presidential nomination, it needs to turn around and search for limits, institutional or temporal, on this long-running essence of nominating politics.2

The Bandwagon Dynamic

Two landmarks in the literature of presidential nominations played an outsized role in the new effort to understand those nominations more systematically. So they provide an essential introduction to the general contours of nominating politics as these have come to be understood, especially when the effort is to organize a comprehensive approach to nominating politics that can move on from this understanding, separate fundamentals from ephemera, and align both from the broad and distant to the narrow and proximate ends of a funnel of causality. The first landmark was a journal article from Donald S. Collat, Stanley Kelley, Jr., and Ronald Rogowski on “The End Game in Presidential Nominations.”3 The second was a book-length treatment from Larry M. Bartels on Presidential Primaries and the Dynamics of Public Choice.4

The most remarkably condensed summary of a grand dynamic underpinning the politics of presidential nomination—and hence the inescapable evidence not just of its existence but of its power—was gathered by Collat, Kelley, and Rogowski in “The End Game in Presidential Nominations.” Looking at the majority-rule nominating contests from 1848, effectively the point by which national party conventions with detailed records were institutionalized, up to 1980, the most recent contest before their own publication date, these authors searched for—and found—evidence that a common set of shared calculations, contributing a common dynamic, governed every one:

This study shows that a simple, empirically derived rule accounts well for the outcome of multi-ballot, majority-rule conventions in the period 1848-1948 and that the same rule would have enabled one to predict correctly the outcome of all contested presidential nominations since 1952 before any candidate had achieved majority support in the Associated Press’ poll of delegates.5

What they elicited from over a hundred years of presidential nominations by way of national party conventions was nothing less than a law-like description of its behavioral operation across time. In this, when the most recent increments to delegate support for particular candidates were added to their existing totals in any given year, there would always come a point when the resulting new totals could no longer be overcome by any candidate who was not in the lead at that particular point in the process. Yet now, this point could be specified precisely, and it was always the same, at least for parties which operated under the requirement of a simple majority for nomination. There might be many ballots to come in earlier conventions or many delegates to be chosen in a later era, but nothing that occurred with regard to either would ever derail a candidate who had already passed this one particular statistical point.

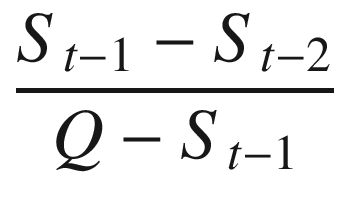

Moreover, what was being elicited here, and what proved its power in a parallel fashion in all such presidential nominations, could be given a precise statistical description. In some vague and abstract sense, the twists and turns of the real world of nominating politics could in theory have caused the resulting summary statistic to be misleading. But in actual practice, no matter how different the relevant nominating campaigns were, the same formula could not just always be applied; it would always be accurate, revealing, and decisive when the evidence could be presented in the appropriate format. The authors called their product “the Gain-Deficit Ratio,” and they could offer it in one simple formula, whose key terms could be specified explicitly:

St–1 represented a candidate’s delegate support in the most recent test. In the early years, this was the most recent convention ballot; in later years, it would be the most recent delegate survey. St–1 − St–2 represented the change in a candidate’s support from the immediately preceding test, be it a ballot or a survey. And Q represented the minimum proportion of the vote sufficient to nominate.

In practical political terms and in their words, “The ratio takes account of where the candidate is,...