1.1 The Narrative Construction of Reality

“When a 演戲 Yǎnxì traditional performance takes place in 水尾 Shuiwei, I will give you back your money.” This is one of the first sentences I heard about Shuiwei village. The meaning of this joke is that you will never get your money back, because in Shuiwei village no yǎnxì is ever performed. As Taiwanese people know, a yǎnxì performance is offered to thank the deities for a gain, or because one has been released from a vow, or because of a happy event within the family. Usually a “stage-truck,” a truck that carries a stage for performances, is parked in front of the temple or in front of the house where the yǎnxì is to be offered. Since the stage is positioned just in front of the main door of the temple, and since these shows are followed by few if any spectators, it is clear that the recipients, the real audience for these performances, are the deities and not the people.

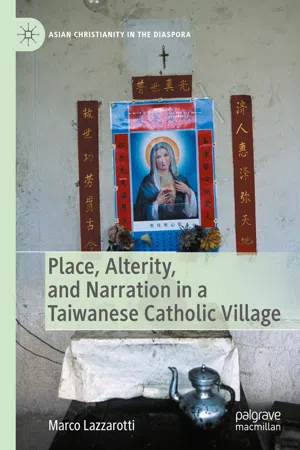

The meaning of this joke derives from the fact that Shuiwei village is, for the most part, inhabited by Presbyterians and Catholics.1 Consequently, no such performances are offered to any deity. Shuiwei is located in the northern part of 崙 背 鄉 Lunbei Township, just south of the 濁 水 溪 Zhuóshuı̌ Stream that marks the border between the counties of 彯化縣 Changhua and 雲林縣 Yunlin.

This small village was the first village in Lunbei Township to accept the Christian religion. A majority of the villagers are still either Presbyterian or Catholic (廖救玲 2005). This large Christian community has had more than 100 years of interaction with the population of Lunbei. The evidence of these interactions can be found in the expressions, the words, and the stories that non-Christian people use in order to describe and contextualize the Christian community of Shuiwei. In the same way, this long interaction is also perceived in the words and stories told by the people of Shuiwei to describe both themselves and the non-Christian members of their community.

I had the opportunity to live in Shuiwei for three years, from August 2008 to October 2011; or more accurately, I spent one year in Lunbei and two years in Shuiwei, during a ten-year period living in Taiwan. Early in June 2008, my wife and I, hopeful and curious, arrived in this village almost by chance. At the time I was doing research into the effect of Catholicism on the tradition of ancestors’ rites in Taiwan, while my wife was looking for a suitable place to carry out her fieldwork on Hakka people.2 We spent the spring of that year visiting all the Hakka communities in both the north and south of Taiwan. Finally, my MA supervisor introduced us to his former classmate who was living in Shuiwei and to the parish priest of that little community. He presented Shuiwei village to us as a place where most of the population were Christian and where the inhabitants introduced themselves as Taiwanese people, but with Hakka ancestors . After a couple of visits, we decided to settle in Lunbei and, as my wife started her fieldwork, I started to think about what kind of project I could undertake for my PhD.

My project, and therefore this book, was born in the field. I had arrived in Shuiwei without a study plan and without a research project. The fundamental reason I had come was to follow my wife during her fieldwork. I did not create an abstract model that had to be verified (or disproved) through research in the field. The topic somehow made its own way to me during the time I spent in Shuiwei. It prompted me every time Lunbei people told me: “Shuiwei is a different place,” or every time they told me: “Are you doing research on religion? You should go to Shuiwei, they are all Christians there.” Many, if not all, of the narrations about Shuiwei made by the people of Lunbei spoke about difference. It is because I wanted to understand why and how this sense of diversity was manifested in these stories that I realized that this place was constructed as “a different place” and that it was constructed, above all, by narration.

The aim of my thesis was to show how the narration of stories about this particular place, Shuiwei, attaches to it a special agency . With this book I would like to share with a wider audience the results of this research: that the narration of stories is not only a consequence of the encounter of different cultures, faiths, and traditions but is perhaps the basic way in order to create cultures, faiths, and traditions. By narrating, telling, and naming the world, we substantially create it. We create a Narrative World .

The stories that I have chosen from those collected during my fieldwork include both stories and anecdotes that I have either been told or witnessed directly myself. I want to present both stories and anecdotes because it is through them that, when I was in Shuiwei, I tried to understand how people act or react in and to certain situations. In other words, they will help the reader understand the symbolic context of where people live. I have chosen this way because I consider both stories and anecdotes as narrations, since they have been narrated at least by myself. This choice mirrors the essence of anthropology, which I have always considered a comparative discipline. There is always a comparison going on between the anthropologist and the local culture, between the anthropologist and academia, and also between the outcome of the anthropological work, the text, and the reader. Stories, as well as anecdotes, are always linked to the present and with the practical and contingent situations which both the storyteller and the audience meet in everyday life.

Among the narrations about Shuiwei, the narratives that I heard from people who live outside this village occupy a privileged position. I decided to give greater importance to these stories for several reasons. First of all because in the context formed by the storyteller and the audience, great importance must be assigned to the cultural background of the interlocutors. Within this context, which I call the Circuit of Narration (Locus, Sect. 2.2.1), the cultural background of the interlocutors plays an important role: it selects the facts that create stories and provides the storyteller with the symbols which help him to select the facts that will become a story. At the same time, the cultural background provides the audience with the symbols which help her/him to interpret the story. In the case of Shuiwei, very often the frames of meanings through which both the storyteller and the audience are able to read the reality and interpret it are not the same. During my fieldwork, I noticed how the stories about Shuiwei were emerging both from the contrast between the storyteller and the frame of meanings that led the actions of the main actors of his stories and from the contrast between the storyteller’s and the audience’s cultural schemes. Through this contrast present inside the Circuit of Narration, symbols, concepts of the world and of the other, and consequentially stories are revisited and created.

There is another reason that convinced me of the importance of stories coming from people living outside Shuiwei. The reason lies in the fact that generally, scholars who analyze and work with the concept of “agency of place” use this idea in order to demonstrate how a specific place, linked with particular memories and facts, is able to produce a feeling of “belonging to a particular place.” In other words, they stress the importance of the agency of place in order to explain how a place influences and shapes the sense of identity of a certain group of people. While basing myself on these studies, I would like to take the discussion a little further. In fact, the particular character of my fieldwork place allows me to affirm that we must put these above-mentioned research frames in a wider context. We cannot limit the potentiality of an agency of place to a discussion about identity and a sense of belonging. The theoretical implications of considering a place as an element full of agency power could lead us to do some very interesting theoretical experiments. But, as a first step, we have to put within this context elements such as narration and storytelling.

I will argue that it is through the narrations that Shuiwei is created as locus , where locus is a place where different historical roots, cultural traditions, personal experiences, and above all narrations meet and confront each other. In other words, locus refers to a place where alterity , or otherness , is discovered and reconceived according to narrative criteria.3

1.2 Ethnography and the Field

The Catholic community of Shuiwei has been the focus of my ethnographic fieldwork, although I also had very deep and fruitful exchanges with the Presbyterian community and with villagers who had not joined the Christian faith. Within the Catholic community of Shuiwei, I especially focused my attention and my analysis on one specific lineage—the 鍾 Zhōng family. I chose this approach because the Zhong family was the first family to convert to Catholicism more than 100 years ago. The influence of this family on the conversions that followed, both in the village of Shuiwei and in the township of Lunbei, was and still is very big. It was with these first conversions that the missionaries started to have contacts and interact with the Lunbei area. Moreover, the anthropological analysis of this family will be helpful to understand the situation of the whole Catholic community in Lunbei.

During the perusal of this work, the reader will note how every entity (the Zhong Catholic lineage, the Catholic and the Presbyterian communities in Shuiwei, the Christian community of Lunbei, the non-Christian inhabitants of both Shuiwei and Lunbei) is never independent, but part of a system of relations that contribute to assign to each entity a specific value. These entities are interconnected and interdependent in many moments of daily life and above all within the Circuit of Narration. Their interactions and their narrations create the locus , the concept I would like to introduce in the field of anthropology of space and place (Locus, Sect. 2.3.3).

Among this relational system is located the anthropologist, who cannot but observe how complex the relationships between the different entities are. These different entities continuously intersect one another and contribute to form the “field” where the anthropologist should discover and select the data. In the process of writing this book, I reached a point where I had to decide whether to try to reduce the complexity of these relations to a more focused (and manageable) ethnographic description or to choose the interactions of these mentioned entities as the target of my research as suggested by Standaert (2011, p. 214) (please refer to Locus, Sect. 2.3.3).

The first choice concretely entailed focusing my ethnographic writing toward the description of the Catholic branch of the Zhong family in Shuiwei. This option, a quite traditional one, has the advantage of having a clear focus, but at the same time it covers up (eliminates, reduces, you name it) the presence and the importance of the other elements that I met in the field and with whom I (and more important the Zhong Catholics) constantly interacted.

The second option led me toward the discovery of locus as a place for interactions and made by the interactions of different agents and by their narrations (Sect. 2.3.3). The analysis of...