Introduction: Furious Wenches

The last recorded instance of the use of the ducking stool as a form of punishment in the UK was in the year 1809. The accused was a woman named Jenny Pipes; her crime was that of being a ‘common scold’, and for having uttered ‘foul and abusive language’.1 The ducking stool was frequently used to discipline women who were deemed to be ‘gossips’ and ‘shrews’ in Europe and the English colonies of North America. It was a wooden chair into which the offender was strapped, which was then submerged in water—in this particular case, Jenny Pipes was ‘ducked’ into a cold English river in the small town of Leominster, Herefordshire. This practice, which became prevalent in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, was designed to publicly shame and humiliate those women whose language was deemed to be transgressive, threatening, rebellious or otherwise unbecoming of women. The story of Jenny Pipes—otherwise known as a ‘furious wench’—caught my attention for many reasons, but mostly because the location of this historic punishment was a town just a few miles from the place where I grew up. The term the ‘ducking stool’ was actually very familiar to me, as a pub in Leominster is named for it. I spent many an evening in The Ducking Stool, but without ever questioning, or being told about, the origins of its name. Jenny Pipes took on a particular resonance for me in the writing of this book, and thinking with her—or at least the very little is known in recorded history about her—helped the key concerns of this book come into sharper focus. What can her story tell us about the ways that women’s voices have been policed, demeaned and punished, and how this relates to changing gender power relations? And how might a historical frame help us to understand the persistent forms of gender inequality and patriarchal power in relation to voice in the contemporary context?

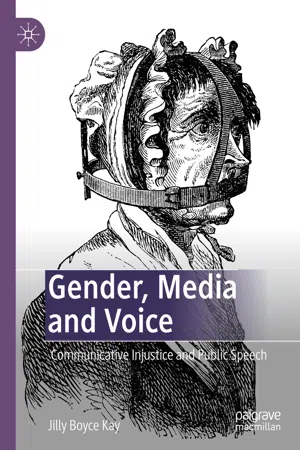

While brutal forms of state-sanctioned punishment such as the ducking stool, and the illegal but widely used scold’s bridle (an iron instrument used in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that literally silenced women by forcing their tongues down with a metal spike), are no longer in use, it is clear that deep and insidious gendered inequalities persist in relation to voice and public speech. As Mary Talbot points out, the English language has an astonishing variety of words for vocal women, all of which have deeply negative and condemnatory connotations; as well as ‘scold’, these include words such as shrew, gossip, nag, virago, harridan, castrating bitch and battle-axe (Talbot 2010, p. 185). There is no such equivalent genre of terms relating to men and speech. Anne Karpf notes that, throughout much of history, the idealised mode of speech for women has been not to speak but rather the opposite: to be silent (Karpf 2006, p. 156). Aristotle proclaimed that ‘Silence is woman’s glory’ (ibid.); he warned that if women became involved in political activities, their wombs would dry up (Talbot 2010, p. 185). This notion linking women’s public speaking with abject infertility persisted well into the nineteenth century (Karpf 2006, p. 157). In myth, literature and culture, vocal women are routinely punished, and silence is re-installed over and over as a redemptive feminine virtue. In Greek myth, the talkative nymph Echo is punished with the loss of her voice; in fairy tales, the Little Mermaid must forfeit her voice in order to live a fully human life (ibid.) (and in Hans Christian Anderson’s version, literally has her tongue cut out). The feminist linguist scholar Deborah Cameron notes that even now, in the contemporary context, to mute one’s voice as a woman might still bring social benefits and a certain (if circumscribed) power: silence is ‘a form of symbolic capital that women may have something to gain by deploying’ (Cameron 2006, p. 16). My mother was told in her childhood in the 1950s and 1960s, as many girls were, to not ‘make a poppy show of herself’ by speaking too much or too often. In the run-up to the US presidential elections in 2016, Hillary Clinton was persistently criticised for her voice, which was often likened to that of a ‘nagging wife’.

Helen Wood shows how feminist theory has sought to map the relationship between the gendering of speech and gender inequality more broadly—because the connections are so indivisible (Wood 2009, p. 15). The values and norms that shape dominant understandings about which forms of talk are acceptable for women—and which are aberrant—cannot be separated from wider and material forms of gender inequality. The gendering of speech—the values accorded to ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ speech genres, and the invisibilised but deeply ingrained assumptions about who is entitled to speak in public—all contribute to broader structures of gender injustice and the continuing subordination of women and other ‘others’ in public life and culture more broadly. However, I argue in this book that inequalities in language-use and public speech should also be understood as themselves constituting a deep form of gender injustice.

Women and Public Speech: A Culturally Awkward Relationship

The classicist Mary Beard has written about the histories of women’s public speech in western culture, and the profound difficulties associated with women’s public voices, which she argues stretch back to classical antiquity. In Ancient Rome, ‘[p]ublic speech was a—if not the—defining attribute of maleness […] A woman speaking in public was, in most circumstances, by definition not a woman’ (Beard 2017, p. 17). She identifies a ‘culturally awkward relationship between women and the public sphere of speech-making, debate and comment’ (ibid, p. 8, my emphasis); this relationship has been forged across millennia and still sets the tone for the contemporary public sphere. Indeed, Beard was motivated to write about this topic after her own experience with misogynistic trolling after an appearance on the UK’s topical debate television programme Question Time (BBC One, 1979–present; this show is discussed in detail in Chap. 7). As such, she writes, when it ‘comes to silencing women, Western culture has thousands of years of practice’ (Beard 2017, p. xi). The punishment and humiliation of women who dare to speak out, particularly on political matters, has not been an aberration in the development of the western liberal-democratic public sphere, but rather has been foundational to and constitutive of it (see also Fraser 1999).

We might understand, then, that pernicious gendered inequalities are ‘baked in’ to the western public sphere. However, it is also important to note that women’s relationship to public speech has not been static or unchanging; the sheer staying-power of misogyny does not equate to uniformity in its manifestations. Rather, women’s relationship to public speech has been changed and resignified in different social, economic and political contexts. For example, Silvia Federici (2018) points to shifts in this regard in the early modern period. She shows how the deteriorating status of women in sixteenth-century Europe was bound up with an intensified devaluing and punishment of women’s speech: this occurred through practices such as the aforementioned ducking stool and the scold’s bridle, as well as the new demonisation of ‘gossips’, and the resurgent imperative for women to be quiet and subservient to their husbands. It was those expressly identified as ‘witches’ and ‘scolds’ who were subjected to the most horrific and humiliating public torture, but the effect was to terrify women as a whole into subservience (Federici 2018, p. 40).

Federici’s work also illuminates the ways in which practices that seek to silence, shame and discipline unruly women have been central to the development of capitalist power. Female sociality, she writes, had to be destroyed in order for the land enclosures and appropriation of communal property to occur in the early modern period, because women’s inter-relationships and the forms of knowledge they produced and shared represented an intolerable form of communal social power. It was therefore the collective voices of women—as well as the collectivity that women represented—that needed to be silenced, disciplined and dispersed; as Federici argues, the figure of the witch was despised as a kind of ‘communist’ of her time (ibid., p. 33); she was a threat not just to patriarchy but also to private property and capital accumulation. It was in this context that women’s talk more broadly came to be feared, belittled and despised. Whereas the word ‘gossip’ had once signified female friendship and attachment, at the dawn of modern England, it came to signify ‘idle, backbiting talk [….and] sowing discord, the opposite of the solidarity that female friendship implies and generates’ (ibid., p. 35). To this day, the word ‘gossip’ conjures up a figure both of ridicule and of potential threat.

Dale Spender (1980, p. 108) notes how women talking together—or ‘gossiping’—actually can be a threat to patriarchy (Federici would also say to capitalism): ‘When women come together they have the opportunity to “compare” notes, collectively to “see” the limitations of patriarchal reality, and what they say – and do – can be subversive of that reality’. The reason that patriarchy has been—and continues to be—so invested in the containment of women’s voices is because they represent a genuine threat to its power. And, crucially for the analysis in this book, it is collective rather than individual voice that has the most capacity for subversion, and which I argue we need to privilege in theories of women’s voices. Federici’s conceptual linking of the violent treatment of women’s speech with broader aims of social control and economic appropriation can cue us in to the kinds of women’s voices that are most likely to be castigated and silenced: those which transgress patriarchal ideals of femininity as well as threaten capitalist relations of power. In the early modern period, it was those women whose forms of knowledge and social practices stood in the way of capital accumulation whose speech was most brutally punished. How might similar technologies of power operate in the contemporary communicative context of neoliberalism?

Speaking as a Woman: Voice in Neoliberal Culture

Of course, the communicative landscape has changed utterly since women were exhorted to be silent in Ancient Rome, since witches were burnt at the stake in early modern Europe, or since Jenny Pipes was ducked in nineteenth-century Britain. We might say that in contemporary culture, in contradistinction to earlier periods, women and girls are now called upon—and indeed expected—to come forward, to speak up, to express themselves and to ‘find their voice’. In a media culture characterised by ‘popular feminism’ and fuelled by a growing ‘self-esteem’ industry (Banet-Weiser 2018), the idea of ‘authentic voice’ and self-expression are increasingly prized as communicative attributes. Rosalind Gill and Shani Orgad (2015, 2018) argue that women and girls are now urged to be confident, upbeat, optimistic and resilient—indeed, to be so is less an invitation than it is a new ‘imperative of our time’ (Gill and Orgad 2015, p. 324). As such, the ways that neoliberal culture compels us to speak, and mandates self-confidence as a celebrated feminine virtue, appears to represent a profound qualitative shift in the gender politics of the public sphere, which, as we have seen, has previously prized quietude and subservience as idealised communicative modes for women.

The development of media and communication technologies in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries has often been associated optimistically with progressive changes towards a more democratic ‘voice’. We can see this in the role of radical newspapers in the extension of the voting franchise to women and the working class; a new openness...