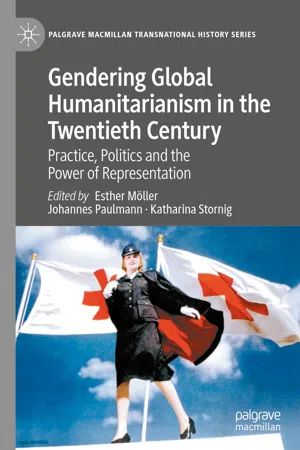

During the Second World War, the American Red Cross produced a poster entitled “Volunteer for Victory”. Showing a woman in uniform posing in front of two Red Cross flags, the poster was aimed at mobilizing American women to volunteer for humanitarian war service. We have chosen a detail of this poster for the cover of our book because it concisely expresses its subject: the multiple, complex and at times paradoxical influence of gender on the history of twentieth-century humanitarianism. Indeed, the poster addresses precisely the three themes that guide this volume’s conceptual approach. On one level, it promoted humanitarian war service in the 1940s by playing upon contemporary notions of femininity and masculinity. While the poster confirmed (or even exaggerated) modern, white and middle-class standards of femininity, dress (including gloves, heels, trendy blond hair and makeup) and beauty, it also flirted with the idea of transgressing gender boundaries by embarking on a national military—and thus masculine—adventure. On a second level, the poster alluded to the intersecting politics of gender and humanitarianism that can be traced through historical instances across the twentieth century. Promoting the American Red Cross as a patriotic enterprise and suggesting the promise of female heroism, the poster indicated the progressive (or even empowering) potential of humanitarian war service by providing women access to the military and to the European frontlines; it depicted white American women volunteers as not only integral to but also active parts of a national “we” represented by the American military forces that were defending Western liberalism. And yet, the imagery remains highly stereotypical and does not question women’s roles as subordinate partners and complementary forces of men, confined to delivering aid in armed conflict. Thus, on a third level, the poster points to the power of gendered representations in the context of humanitarian narratives and media communication: the volunteer depicted is young, beautiful, healthy and athletic yet delicate and in motion, signalling that she is ready to take action on behalf of her needy compatriots and to complement male combat activities. In sum, the poster demonstrates the deep entanglement of notions of gender and aid service in humanitarian discourse and practice at a specific moment in history.

This volume discusses the relationship between gender and humanitarian discourses and practices in the twentieth century. Humanitarianism is understood here, in accordance with recent scholarship, as a field that covers a broad range of activities, including emergency relief, longer-term development and active response to famine, ill-health and poverty.1 The volume reminds us that gender mattered not only to different phenomena of conflict and crisis but also to the various humanitarian responses to them. Humanitarianism, we argue, is fruitfully approached as a gendered enterprise, for, at specific times and in particular places, its discourses and practices were profoundly affected by gendered norms, hierarchies between men and women and cultural ideas of what it meant to be male or female. Understanding gender as a relational category that includes both femininity and masculinity allows us not only to challenge essentialist approaches but also to explore the ways in which gender difference functioned in the formation of cultural and social relations and worked as an axis along which inequalities of power were established, maintained and, in some cases, changed.2

The chapters in this volume present a gender perspective on issues such as post-genocide relief and rehabilitation, humanitarian careers and subjectivities, medical assistance, community aid, child welfare and child soldiering. They further give prominence to the beneficiaries of aid and their use of humanitarian resources, organizations and structures by investigating the effects of humanitarian activities on gender relations in the respective societies that are examined. Approaching humanitarianism as a global phenomenon, the volume considers historical actors and theoretical positions from both the global North and South (from Europe to the Middle East, sub-Saharan Africa, South and South East Asia as well as North America). It combines Western and non-Western perspectives as well as state and non-state humanitarian initiatives, and it scrutinizes their gendered dimensions on local, regional, national and global scales. Finally, some of the chapters illuminate the impact of feminism on both the development of global humanitarianism in the twentieth century and its rapidly growing historiography. This is especially important given that the volume concentrates on the period between the late nineteenth century and the post-Cold War era, which not only witnessed a major expansion of humanitarian action worldwide but also saw fundamental changes in gender relations and the gradual emergence of gender-sensitive policies in humanitarian organizations in many Western and non-Western settings.

Although the history of humanitarianism has recently attracted a great deal of scholarly attention, surprisingly little has been said about the workings of gender in this globalizing enterprise. So far, the few scholars of humanitarianism who have addressed gender have largely limited themselves to either pointing out the many ways in which women contributed to humanitarian movements or to problematizing the depictions of men and women that have featured in humanitarian representations and narratives. In the first part of this introduction, we will discuss these important trends in the recent history of humanitarianism and then introduce two well-established topics in the field of gender history that are crucial to the study of humanitarianism but that have, so far, been little recognized: gender histories of care, and studies of the gendered dimensions of war, violence and armed conflict. We not only suggest that the histories of humanitarianism and of gender would benefit from an intensified dialogue but also seek to steer this dialogue towards a rigorous exploration of the relationship between gender and humanitarianism. In the second part of this introduction, we outline our conceptual approach, which also provides the structure of this volume. While introducing the chapters, we develop three conceptual fields that we consider of upmost importance for systematically tracing the intersections between gender and twentieth-century humanitarianism: masculinities and femininities in humanitarian discourse and practice, gender and the politics of humanitarianism and the power of gendered representations. In our view, a conceptual (rather than a chronological or geographical) approach is necessary to achieve the volume’s goals, which have two main aspects. It aims to investigate how constructions and relations of gender shaped and were shaped by humanitarian encounters, practices, programs and subjectivities throughout the twentieth century. And by engaging with a topic that necessarily transcends local or national frameworks of analysis, the volume also strives to contribute to the larger current debate about the place of gender in transnational or global history.3 Consequently, we conclude the volume with a chapter that goes beyond summarizing the results of the individual contributions and lays out an agenda for future research into the gender histories of humanitarianism.

Introducing Gender as an Analytical Category: Review and Prospects

In a recent article, historian Abigail Green, reviewing the large body of new literature published on humanitarianism by historians and social scientists, argues that the role of women in this enterprise since the nineteenth century still remains to be fully explored and added to the story.4 According to Green, the historical study of humanitarianism is to a great extent about the study of people who were moved to action by “their identification with the suffering of distant others” in historically specific situations and contexts.5 Many of these people happened to be women, yet their contributions, ideas, reflections and voices have often remained unheard by scholars who have failed to reflect upon gender-biased structures, divisions of labour and power relations in humanitarian encounters, organizations and archives. Other than women’s roles in the British and international antislavery movements (which have received considerable scholarly attention over the last two decades6), their contributions to nineteenth- and twentieth-century humanitarianism remain understudied. This is particularly the case for those numerous women who were not in the forefront of the social or humanitarian reform movements of their time. Instead, some well-known figures such as Josephine Butler (1828–1906),7 Florence Nightingale (1820–1910)8 or Eglantyne Jebb (1876–1828),9 have become veritable humanitarian icons and even made it into mainstream histories of humanitarianism.10

Yet, some recent research has started to broaden this focus on individual women activists (who have often been constructed as remarkable or exceptional women) by concentrating on female-centred archives as well as by studying the ways in which organized groups of female aid workers (e.g. nurses), feminists or development experts drew greater attention to the needs and life situations of women and men in crisis, disaster and war.11 This research has particularly highlighted the large number of women who were actively engaged in the various national Red Cross and Christian missionary societies as, for instance, wartime nurses, doctors and health workers.12 Historian Inger Marie Okkenhaug, for example, has studied the encounter between a Norwegian missionary, nurse and midwife and female Armenian refugees in Mandate Syria with the goal of shedding light on the often-neglected experiences, activities and perceptions of women during and after the genocide.13 By taking into account the large numbers of women present among religious aid workers after 1918, scholars have examined the key roles that women played in gradually transforming missionary work into humanitarian service, development aid, welfare work and later development cooperation.14 Taken together, these “additive” studies that have deliberately focused on female activism certainly suggest that women’s efforts were constitutive to modern humanitarianism, contributing huge amounts of voluntary work and providing a basic prerequisite for the emergence of humanitarian movements and institutions. Green and others thus rightly plead for more studies focusing on the engagement of “ordinary” women in h...