Introduction

Structuralists 1 note the existing widespread vicious circle of poverty in the developing countries, and believe the development of inward-oriented import substituting industries (ISIs) is a necessary condition for development. 2 The fundamental belief is that development is a process of structural transformation from the primary sector (agriculture and mining) to the manufacturing sector. In order to achieve this, they emphasize the role of government in planning and control as a means of allocating resources, because they are fundamentally sceptics with regard to the role of a price mechanism. In order to promote the manufacturing sector, emphasis is also placed on protecting local manufacturing industries (protectionism) from foreign competition. Protectionism substitutes expensive capital-intensive domestic manufacturing products instead of importing cheaper manufacturing products. However, the countries that have adopted this strategy have ended up generating capital-intensive ISIs.

Capital-intensive manufacturing requires machinery, equipment, and other intermediate inputs from overseas. To obtain cheaper inputs, it is essential to have an overvalued exchange rate in their inflexible exchange rate system. Overvalued exchange rates make imports cheaper and exports expensive. In addition, there are strong views about foreign dominance in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI) and foreign capital. Such views have existed from Marxist ideology and heavily influence many large developing nations, including India and Latin America. Such views prohibit FDI. Unionism in the labour market has become the norm, which has tremendously influenced all domestic production activities. The countries that advocate an inward-orientation strategy have started addressing all of the above issues, and fully fledged state intervention in all markets has emerged. This chapter explores the inward-orientation strategy and presents the effects and impacts on domestic industrial activities.

Inward Orientation and International Trade

The traditional hypothesis suggests that a country that depends on a few primary commodities for its export earnings is highly vulnerable to price and quantity fluctuations in the export market. 3 Although this hypothesis has been challenged on the basis of cross-sectional data (Massel 1964), subsequent studies on a country-by-country basis tend to support this traditional hypothesis (Love 1979). Consequently, the views on price trends and the adverse impacts are consistently reviewed and debated in the literature. Based on these premises, Prebisch (1964) establishes a falling relative price of primary products relative to manufactures over the long term (he used a dollar-price index for primary product exports divided by a dollar-price index for exports of manufactures), and his data have been extended periodically by the United Nation Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (Pugel 2004: 317), which unambiguously reveals the lowering trend of primary product prices. Thus, to overcome such uncertainties that primary products generate, primary-producing countries tend to switch into import-substituting manufacturing activities, believing that the manufacturing sector may act as an engine of growth.

In 1964, forming the UNCTAD, it was argued that developing countries are highly dependent on primary products, and are hurt by a long-term downward trend and short-term instability in primary product prices. Export shares of a few primaries in total exports were very high in developing countries and therefore they have been hurt by falling prices (Love 1983). For example, Brazil depended on coffee for around 95 % of its total earnings in 1959, and the price of coffee weakened deeply after 1982. Commodities such as cocoa, sugar, copper, tin, wheat, and rice have also had the problem of falling prices since 1900 (Pugel 2004). Primary product prices were depressed severely during World War II and the Korean War during 1950–53, and had a boom in the early 1970s. Overall, the change in relative primary products to manufactures has not been in favour of primary-producing countries, and the trend has been downward.

Why are primary products subject to a deteriorating price trend in the long run? This is mainly due to, on the one hand, price and income inelastic nature, and on the other, conditions subject to supply-side restraints. The majority of the primary products are subject to price inelasticity as a result of these small changes in production, producing large changes in prices. They are income inelastic: as income raises the demand swings towards luxuries and not towards farm products. The primary sector is also subject to technological advancement and is widely known as the ‘green revolution’, and has ended up in over-production, lower prices, and lower farm income. Technology advancement occurs by the improvement of land management, soil conservation and irrigation, the introduction of hybrids, electrification, and the mechanization of farms. On the contrary, farm production is involved with a gestation period to bring the product to the market, which also impacts the supply side and is subject to natural disasters.

Deteriorating export earnings and wide short-term fluctuations in export earnings around the trend became the focal point of the discussion in the post-world war literature. Short-term instability is a common problem, possibly determined by the degree of price instability, along with the degree of quantity instability. Instability in export earnings affects the economy in a number of ways. Wide fluctuations can cause a fall in fiscal spending due to the fall in government revenue from export taxes and duties. Consequently, domestic instability occurs, which makes the task of development planning difficult, and lowers the efficiency with which investment resources are used. Thus, short-run fluctuations cannot be ignored or overlooked in any economy that is heavily dependent on a few primary exports.

The unreliable nature of farm income caused by deteriorating export earnings could reduce further investment capacity and affect consumption patterns. Lower income to farmers also means lower wages and lower productivity in the farm sector, and this will eventually lead to a vicious circle of poverty. The emerging poor are identified as periphery by the structuralists, where the primary product export sector generates fewer jobs with a consistent reduction on wages. Instead, manufacturing-producing countries are identified as centre and have increased trends in prices and the productivity growth in the centre is reflected in greater wages. Based on the above scenario, structuralists identify two entirely different groups, characterized by their productivity and wages in one periphery (lower productivity, lower wages, and a vicious circle of poverty) and the other centre (higher productivity, higher wages, and higher growth).

There is a large difference between the income elasticity of demand of the centre for the primary goods exports of the periphery, and the manufactured goods it buys from the centre (Prebisch

1964). For the peripheries’ imports, the income elasticity of demand is perceived as significantly exceeding those of its exports. As income rises, the overseas demand swings towards luxuries (manufactured goods) or goods for which the income elasticity of demand is greater than one. For example, 5 % annual average growth of the centre may not produce 5 % more consumption of the peripheries’ primary products, but produces more consumption of luxuries. In addition, substituting synthetic products is widespread for primary products in the process of technology advances (e.g., synthetic rubber and synthetic fibres), and this also depresses primary product prices. The primary sector is also subject to relatively slow productivity growth due to a lack of cost-cutting technology relative to manufacturing (biotechnology is an exception). The fixed costs component in the farm sector is relatively high compared to variable costs. Farmers may not be able to reduce their costs by firing themselves, and therefore labour supply is also a relatively fixed cost.

Table 1.1Export shares (few primaries in total exports) 1959

Afghanistan | 0.89 |

Argentina | 0.94 |

Barbados | 0.93 |

Brazil | 0.95 |

British Honduras | 0.97 |

Burma | 0.97 |

Colombia | 0.80 |

Costa Rica | 0.90 |

Dominican Republic | 0.98 |

Ecuador | 0.97 |

El Salvador | 0.83 |

Ghana | 0.92 |

Guyana | 0.96 |

Honduras | 0.95 |

Indonesia | 0.67 |

Ivory coast | 0.98 |

Jamaica | 0.90 |

Kenya | 0.89 |

Malagasy Republic | 0.95 |

Nicaragua | 0.99 |

Nigeria | 0.88 |

Sri Lanka | 0.99 |

Fiji | 0.88 |

Love (1983)studies the impact of diversification of the commodity composition of exports into manufactures on reducing instability in developing countries’ export earnings. Findings show that diversification into non-traditional exports occurred across a sample of countries; however, this has not resulted in greater stability. The increase in earnings instability of manufactures has been more than the instability of traditional primary commodities. Thus, this study throws some doubt on the traditional view that developing countries will reduce short-term export earnings fluctuations by reducing the commodity concentration.

Weiss (

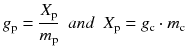

1991) shows the structuralists’ sustainable growth rate model for the peripheries considering the growth of exports and imports in a simple equation. Equation (

1.1) accommodates the centre and periphery argument:

where

g p is the sustainable growth rate in the periphery,

m p is the periphery’s income elasticity of demand for imports from the centre,

X p is the rate of growth of exports of the periphery and

g c is the growth rate in the centre. The centre’s income elasticity of demand for imports from the periphery is

m c, where

m p >

m c.

From Eq. (1.1), sustainable growth can be achieved by either raising exports or reducing the income elasticity of demand for imports, or both. Various attempts have been made in the developing countries to raise exports or reduce imports to attain sustainable growth, but these have been unsuccessful. The prevailing pessimism for the export case for primary products has been a major barrier to increase exports. To overcome the adverse situations in the commodity exports (numerator), various commodity agreements are entered into. Commodity agreements include global buffer stock agreements, global export quota agreements, and compensatory financing. Alternatively, substituting manufacturing imports (denominator) domestically by adopting capital-intensive technology has been a difficult task for the periphery.

Commodity-producing nations (with the support of consuming nations) have created an international agency to monitor the quantity of the commodities under international buffer stock agreements (e.g., tin, rubber, and cocoa agreements). The agency is expected to buy the commodity when the price drops below the expected minimum price and sell when the price increases. For buffer stock agreements to be successful, the high cost of storing...