eBook - ePub

Southern Anthropology - a History of Fison and Howitt's Kamilaroi and Kurnai

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Southern Anthropology - a History of Fison and Howitt's Kamilaroi and Kurnai

About this book

Southern Anthropology, the history of Fison and Howitt's Kamilaroi and Kurnai is the biography of Kamilaroi and Kurnai (1880) written from both a historical and anthropological perspective. Southern Anthropology investigates the authors' work on Aboriginal and Pacific people and the reception of their book in metropolitan centres.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Southern Anthropology - a History of Fison and Howitt's Kamilaroi and Kurnai by Helen Gardner,Patrick McConvell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Storia & Storia dell'Australia e dell'Oceania. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Southern Anthropology

1

Introduction: The Publication of Kamilaroi and Kurnai

In August 1880, Victorian colonial publisher George Robertson posted copies of a new title, Kamilaroi and Kurnai, to the co-authors Lorimer Fison and Alfred William Howitt. Fison’s arrived at the Fiji Methodist training college of Navuloa near the growing port town of Suva, on the island of Viti Levu. Howitt’s copies were posted to the isolated Gippsland town of Bairnsdale, in the south-eastern corner of the Australian colony of Victoria, where he managed the huge magistracy of the region. Their book described the social structure of the Kamilaroi (now Gamilaraay) people of northern New South Wales, and the lives of the Kurnai (also Gunaikurnai) people of Gippsland, with further details from language groups around the Australian continent and the islands of the Pacific. It was one of many on the original peoples of the region written from the Australasian colonies in the period and was published as book after book concerned with the origins of human society rumbled from the steam presses of Europe and North America.

But Kamilaroi and Kurnai differed from those of the colonies and those of the imperial centres. Fison and Howitt’s book used new methods of anthropological investigation, some of which they had developed themselves and others which they had borrowed from their mentor, American anthropologist Lewis Henry Morgan. Their systematic enquiries of Aboriginal and Pacific Island cultural experts, led them to new analyses and damning appraisals of the popular accounts of indigenous lives produced by key figures in British anthropology. By chance, Charles Darwin was one of the first British readers of the published version of Kamilaroi and Kurnai. He received a complimentary copy from Howitt and declared the book so important that he sent it straight to his friend, John Lubbock – famous throughout Britain for his popular texts on ‘primitive’ people – and correspondent, John McLennan – acerbic Scottish theorist on the origins of human marriage.1 These men were the principal targets of Fison and Howitt’s critique and both were furious at this attack from the Antipodes.

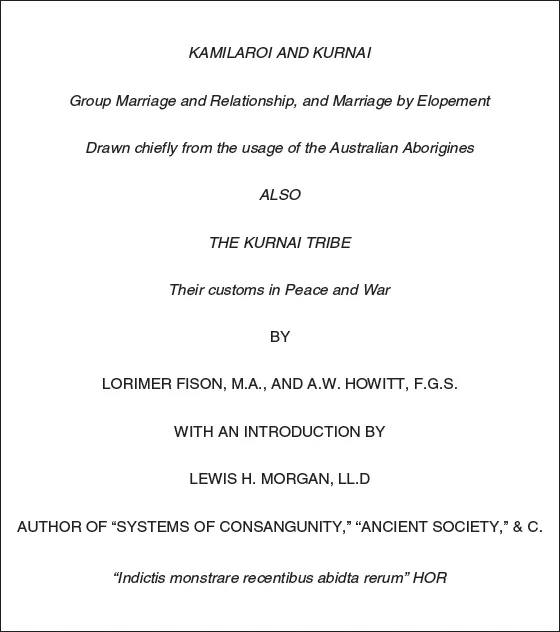

Fison and Howitt had struggled to title this hybrid book of data, analysis and critique that was so different from anything that had gone before it. Following correspondence with Fison and problems at the printery, Howitt consulted Melbourne author George Rusden who suggested Kamilaroi and Kurnai as the short title. This was appropriate for Howitt’s section, which focused almost exclusively on his Kurnai neighbours in the Gippsland region of Victoria. But Fison’s half of the book was at once a careful exposition of the social organisation of the Gamilaraay people and a fierce denunciation of much British anthropology. He also provided regional comparisons of kinship data and social organisation from across the Australian continent and the islands of the Pacific. Fison had suggested that his section be titled ‘A Contribution to Anthropology, based on Australian Customs’.2 But he agreed to Kamilaroi and Kurnai with a cluster of clumsy subtitles (see Figure 1.1).

Lewis Henry Morgan was Fison and Howitt’s mentor and an attraction to potential readers of Kamilaroi and Kurnai given his high profile in both the United States and Britain. Acknowledged as the founder of American anthropology, Morgan had forged a new form of writing on the culture of Amerindians in his book League of the Ho-dé-no-sau-nee, or Iroquois (1851).3 He then established a network of American missionaries and consuls to map the kinship systems of the world and from this evidence published two important books – Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family (1871) and Ancient Society (1877). His preface for Kamilaroi and Kurnai was also a sign, aimed specifically at British readers, of Fison and Howitt’s allegiance in a long-running debate in Anglophone anthropology. From the early 1870s Morgan had argued his findings with Lubbock and McLennan whose counter-theories of human development were based on their readings of the explorer, settler and missionary texts that had flooded the British book trade over the previous eighty years. Fison and Howitt were firmly in Morgan’s camp.

Figure 1.1 Title page of Kamilaroi and Kurnai (Fison and Howitt,1880, Kamilaroi and Kurnai)

The Latin inscription from Horace translates as ‘Reveal by new signs thoughts hitherto unknown’. From the sites of Australia and across the Pacific, from the encounters between collectors and indigenous experts came unexpected evidence that defied a simple translation for the metropolitan audience and suggested not merely new readings of Aboriginal people and Pacific Islanders but also that the ideas and method of much of the anthropology to date was fundamentally flawed. These were the years of evolutionism. Over the previous generation, scholarship throughout Europe and America took a ‘primitive’ turn as the new deep time of the Darwinian revolution suggested that human societies had marched, stalled or regressed along a predetermined path. While earlier natural historians had theorised on the development of human society from a lower to a higher state along specific stages, the 1860s and 1870s were characterised by the intense hunt for the origins of human institutions and the mechanism for change from one stage to another. Throughout these years scholars mined the rich sources of the spreading empires to propose new chronicles on the origins and development of marriage, government, religion and morals, based on the belief that the ‘primitive peoples’ of the world provided a window onto the deep past of human history. In contrast to the library-bound theorists of Britain, Fison and Howitt’s evidence was drawn directly from the lives of the peoples of the Pacific and Australia with profound consequences. Their unruly findings could not be explained within the expected narratives of human development. Kamilaroi and Kurnai showed that those termed the ‘primitive’ peoples of Australia and the Pacific – and by extension all other ‘primitive’ peoples – lived lives that could not be readily classified within the theory of evolving human society along a single line and toward a single goal. Fison and Howitt’s book challenged the nascent discipline and set new standards for the evidence and analysis of indigenous peoples.

Kamilaroi and Kurnai differed from other studies of the period because of Fison and Howitt’s systematic enquiries and revolutionary methodology. Central to their analysis – and to this examination of the writing of their book – was Lewis Henry Morgan’s kinship schedule, a questionnaire developed over a period of ten years during the 1840s and 1850s through meetings with first the Iroquois and then the Ojibwa people. It was revised and extended in the Australian colonies as Fison and Howitt’s investigations required further modifications. Morgan’s innocuous list of kinship questions and tables is in fact a surprising nineteenth-century artefact of deep intercultural engagement. Completing a schedule required prolonged and close collaboration between at least two people reaching across significant cultural divides. Indeed, Fison advised consulting with a relay of people because the increasing complexity of the questions led to mental exhaustion: for example, question 113 asked ‘What is the name for my mother’s sister’s daughter’s husband?’, as spoken by a male, and 209 queried the term for ‘my brother-in-law in the case of my husband’s sister’s husband’. The schedule was difficult. As Morgan noted in his introduction to the publication arising from his global collection of kinship schedules, those few that were returned were almost invariably incomplete and required long correspondence through imperfect postal routes to rectify the problems.4 Work on the schedule required both a high level of partnership and, unlike any other investigation of the period, it required that the investigators be alert to the pitfalls of imposing their own categories onto the kinship systems of others. To overcome this, Morgan suggested that the investigators begin by explicitly defining their own kinship system and only then to attempt to understand the ‘difficulties of another, and perhaps radically different form’.5 This level of reflexivity was rare for the period.

The results, gathered for Fison and Howitt from across the Australian continent and the Pacific Islands at the height of perhaps the most Eurocentric period of anthropological investigation, were both conclusive and unexpected. Here, through the rigour of the schedule were details of the lives of indigenous peoples that went to the heart of their societies. This data challenged the expectations of metropolitan theorists and unsettled the hierarchy of ‘civilised’ over ‘primitive’ people. Howitt’s detailed explication of the Kurnai people anticipated the structuralism of the social sciences of twenty years later. Fison’s passages on the difficulties of the observer trapped in his or her own ‘mind-world’, argued that the hard work of the new science lay not just in the theorising but in the act of engagement with cultural experts and that the study must move from the armchair to the field.

Southern Anthropology explores the conception, writing and reception of Kamilaroi and Kurnai from both a historical and an anthropological perspective. It examines the long genesis of the book’s formation and the artifice of its construction. It tracks between the historical narrative of first Fison’s and then Howitt’s engagement with their stable of correspondents at the sites of encounter from which their material was drawn, and an anthropological analysis of their findings. It is based first and foremost on the materials born of these engagements: the handwritten notes, the completed kinship schedules or later those on social organisation that fired Fison and Howitt’s imaginations and fuelled their thinking. Letters criss-crossed the southern regions of Oceania, across the shorter mail routes of the Australasian traders and the stagecoach connections through the interior. This was an investigation dependent on the globalising world. Requests for information and responses were sent through mail bags to missions in the South Pacific, on the trade routes to China, or via bêche-de-mer or copra traders from the ports of Sydney and Melbourne. Closely-written letters, often ten pages long, were transported between Fison, Howitt and Morgan on the large American steamers that ploughed the Pacific as efforts to establish a regular mail service between the Australasian colonies and San Francisco were trialled through the 1860s and 1870s.6

The letter-writing was prodigious. Over a period of fourteen months from 1869–70, when Fison first became engaged in the study, he wrote 250 letters to 97 correspondents comprising over 900 pages, most of which mentioned his new interest in one form or another. Fison then tore the original from the commercially produced Letterbooks, leaving a press copy behind as his record. From 1873 Howitt joined the conversation from the most remote corner of the colony of Victoria and began to assemble his own group of correspondents for the collection of material. Letters between Fison, Howitt and Morgan almost invariably referred to the post: they lamented the cost of postage and problems posting large parcels; they feared losing books and letters and they responded with excitement over former mail that brought new details and data. These were conversations over months and years that almost invar...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Maps

- List of Tables

- Note on Spelling

- Foreword by Nicolas Peterson

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Part I Southern Anthropology

- Part II Finding Kin: Fison in the Antipodes

- Part III Kin and Skin

- Part IV From Encounter to Page: The Writing of Kamilaroi and Kurnai

- Part V The Reception and Legacy of Kamilaroi and Kurnai

- Glossary

- Bibliography

- Index