![]()

1

Perspectives on Energy, Governance and Profound Change

Introduction

all we have so far, are competing doctrines – sets of normative ideas about the goals to which state policy should be directed and how politics and economics (or, more accurately, states and markets) ought to be related to one another.

(Strange 1988: 16)

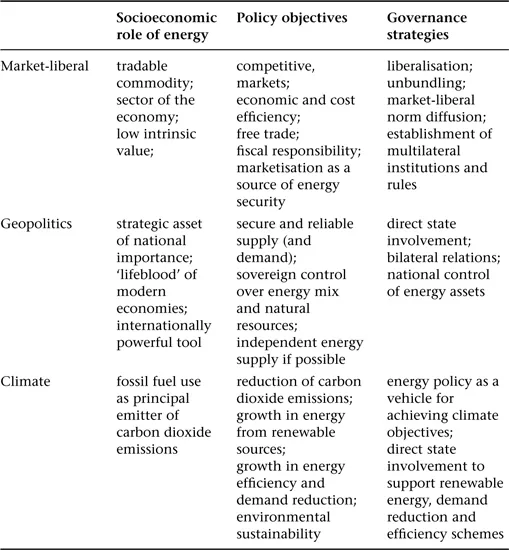

It has been observed on a number of occasions that within the social sciences there are competing doctrines, or sets of normative ideas, about the objectives and organisation of state policy. These also compete to provide explanations of and solutions to problems in the social and political world, and offer ideas about the goals to which state policy should be directed and how politics and economics, or states and markets, ought to be related to one another (cf. Runciman 1969: 156ff.; Smith 1987; Strange 1988: 16). It is within this broader context that energy governance is analysed here. Three primary perspectives are identified as having been influential over energy policy in the 2000s, namely pro-market, geopolitical and climate perspectives. This chapter will be organised around these three different and in some ways competing understandings of, and political approaches to, energy. The pro-market perspective has, as with other areas of research, dominated analyses of UK energy over the past few decades, both in academia and within the Energy Directorate of the DTI. This has left little room for insights from other perspectives offered within the social sciences. More recently, however, geopolitical and climate interpretations have become increasingly commonplace and have had a growing impact on how energy is governed.

It is important to note, at this early stage, that these differing perspectives are presented here more as heuristic devices than as rigid definitions. The boundaries between the perspectives as characterised here are porous, there are some similarities between groups, some ideas overlap, and they are clearly understood as subject to change and adaptation over time. These perspectives are, however, also put forward as largely reflective of genuinely held beliefs about energy and how it should be governed. They are important because they have been, to greater or lesser degrees, influential in government thinking about energy and also because they have underpinned the three energy crisis narratives that are understood here to have had a large degree of influence on energy governance change and on the new system that has evolved. Understanding how these narratives have driven change and influenced type and degree of change is fundamental to explaining change as well as understanding energy governance in the 2010s.

This chapter commences with a definition of each approach to understanding energy and its socio-economic role as well as outlining the sets of corresponding ideas about how it should be governed. It starts from the notion that these different perspectives produce in application particular sets of policy, governance recommendations and structured outcomes and this is a point worth reinforcing given the degree to which, ultimately, the new energy governance system draws on multiple theoretical paradigms. This is followed in each case by a more detailed assessment of the different ways in which each perspective has tended to construct understandings of, and responses to, energy events in the 2000s. In this way these sections fulfil the function of outlining both the ideational and the material context within which energy governance changes were taking place, whilst recognising and emphasising variety over narrow interpretations of events.

There has, however, been one consistent perception across pro-market, geopolitical and climate perspectives, and that is that energy had entered a period of crisis in the first decade of the 21st century. The various ways in which energy crisis has been constructed and understood are shown to be partly constitutive of the range of governance solutions offered. As a generalisation, although each perspective recognises certain core components of energy’s renewed hour of difficulty, different emphasis has been placed on the importance of those components depending on the theoretical approach and/or related, normative position taken. Clearly each perspective may well represent an oversimplification of events but it is important to understand how they have interpreted events in that these interpretations have influenced the type and degree of change that has taken place in energy governance. Although crisis is understood to exist for a range of different reasons it is important to note that a widespread perception emerged in the UK, as elsewhere in the world, that energy crisis exists.

As the review of perspectives on energy evolves an interesting, arguably underanalysed, debate emerges – one that takes place within academic, political, policy-making and public circles. Elements within each of the three perspectives have increasingly begun to consider alongside, and often because of, perceptions of crisis that international energy has entered, or at least should enter, a period of significant change. As might be expected, a range of reasons are offered for change, but arguments have now emerged that change of a profound nature, often referred to as paradigm shift, is ongoing in energy. Debates about energy paradigms and change are utilised within this book as a starting point from which to begin the analysis of change in UK energy policy and governance.

Perspectives on energy

This section defines each perspective of energy, and a summary of each view on the socio-economic role of energy and of what the objectives and instruments of energy policy should be is contained in Table 1.1. As outlined in the Introduction to this book, it is often suggested that there are two competing narratives that currently dominate the analysis of energy governance and policy (Youngs 2009: 6; cf. Correlje and van der Linde 2006; Finon and Locatelli 2008; Luft and Korin 2009: 340). Clearly this kind of debate is not new in IPE terms, and it gives energy analysis from an IPE perspective an impression of being stuck in a bit of a time-warp. But it is at least a debate that recognises that there are differing political approaches to energy both geographically and historically, even if it rarely asks questions about why these different approaches exist. Prior to the re-emergence of this debate, many energy experts had fallen in line with leading energy academic and US government advisor Daniel Yergin, who had in 1998 concluded with regard to energy that ‘it is the economic terms themselves, rather than the philosophy of the terms, over which governments and companies wrangle’ (Yergin 1998a: x).

As with so many other areas of governance, neoliberal economics had become the dominant approach utilised within both energy policy-making and academic analyses in OECD countries from the early 1980s to the mid-2000s (Hadfield 2007; Youngs 2009). By 2001, one much-cited study concluded that international commodity markets had now developed to such an extent that ‘competition is the rule and economics works’ (Mitchell et al. 2001: 176). As recently as 2006, pro-market energy analysts suggested that the ‘old world’ model, which is laden with state guarantees, subsidies and other measures that dampen the ‘pure expression of market forces’, has been rejected by Western nations. The ‘new world’ model had come to replace this old model to the extent that ‘[t]oday almost all consuming markets have adopted plans to allow for a greater role for the “invisible hand” of the market’ (Hayes and Victor 2006: 322). The extent to which this perspective, particularly in terms of appropriate roles for markets and the state, had become accepted amongst energy academics and policy-making elites alike meant that privatised and liberalised energy markets were increasingly analysed as fait accompli as opposed to socially constructed (Egenhoffer and Legge 2001; cf. Helm 2005a; Cherp and Jewell 2011). This indicates the large degree of power that these ideas have had both over governance systems and policies as well as to resist change – themes to which this book returns in Chapter 2.

Table 1.1 Three perspectives on energy

The pro-market perspective on energy

The pro-market perspective is outlined here only in brief, given that chapters 3 and 4 will emphasise this perspective in detail owing to the degree of influence it has had over policy-making internationally, and in the UK, over recent decades. The pro-market view rested largely upon neoliberal economic and rational choice ideas about governance (cf. Hay 2007). One of the fundamental aspects of this perspective, as argued by advocates of neoliberal economic governance practices in the late 1970s and early 1980s, was related to the socio-economic role that energy was considered to play. The post-1945 emphasis on energy’s central role in powering modern economies was de-emphasised in the 1980s when it was suggested that energy should be considered first and foremost as ‘just another commodity’ rather than a national or merit good (Lawson 1989: 23; see also DoE 1982; Littlechild and Vaidya 1982). From this perspective energy, as a commodity, is ultimately fungible or replaceable which implies little or no intrinsic value (cf. Youngs 2009: 7). By 2001 oil, the most dominant and problematic energy source, was understood to have been successfully ‘commoditized’ (Mitchell et al. 2001: 176).

Broadly speaking, therefore, energy should be left to trade on open markets and, to the extent that governance is required, should be pursued principally with an emphasis on economic or cost efficiency over state planning and on ensuring competition (Littlechild and Vaidya 1982). It follows that energy, like other economic sectors, should become subject to processes of deregulation and privatisation as new ideas become implemented and later sedimented (Jegen 2009: 5). The newly emergent freely trading energy markets, once established, should be supported through international co-ordination, based around the setting of generic, good governance standards and multilateral institutions (Youngs 2009: 8). The clear focus within this perspective has been on positive economic interdependence in energy trade, on ‘markets and institutions’, and on their internationalisation and their vital roles in energy governance (Goldthau and Witte 2009; Youngs 2009; Lesage et al. 2010). Much of the original thinking behind promoting the liberalisation of oil markets and pricing was intended to prevent ‘states’ from impacting negatively upon the international oil trade, in that smoothly functioning ‘free’ markets were understood to be the ‘best insurance’ for a country’s security of supply (Mitchell et al. 2001: 177).

The pro-market system of governance which first emerged in the UK, and in Chile under General Pinochet, was underpinned internationally by the emergence of the Washington Consensus within IGOs in the 1980s and 1990s (Held 2006: 161). It was further supported by energy institutions such as the IEA, which assessed the energy policies of member states against what they referred to as the model UK system (IEA 2006: 9). Energy systems around the world were privatised and deregulated, often under the auspices of International Monetary Fund (IMF), WB or EU funding conditions (de Oliveira and MacKerron 1992). Even Russian national resource companies, so long the engine of Russian economic growth, were passed in the 1990s from centralised control to albeit centralised private control in the form of oligarchs.

Geopolitical perspectives

As is the case in other areas of analysis and politics there are clear tensions between the pro-market and geopolitical perspectives on energy, events and governance. As such, the geopolitical perspective on energy can be taken here as a direct critique of the pro-market perspective or, as one analyst put it, of the ‘economistic’ turn in energy analysis (Hadfield 2007: 2). It is worth, however, making a brief point of differentiation here to avoid confusion. Much pro-market research on energy refers to ‘statism’, or resource nationalism, in a blanket fashion as covering a multitude of approaches to energy that is, any approach that assumes state, or political, intervention in energy markets. This might include states pursuing ‘aggressive’ energy relations internationally, such as China, as well as governments deciding on state ownership and management of domestic energy companies, as was evident in the UK prior to the 1980s, but which could also be referred to as socialism. This section of the book, in attempting to avoid analytical confusion between realist and socialist politics, defines geopolitics separately from state socialism.

It could be argued that geopolitical perspectives on energy share a long and well-established history. These perspectives represented arguably the dominant way of thinking in international energy relations, with the emphasis on oil, for most of the 20th century. After the brief hiatus in the 1980s and 1990s, geopolitical perspectives seem to have been substantially revived in the UK and Europe in the mid-2000s, particularly as perceptions that energy is in crisis have deepened (McGowan 2008: 91). This is, as with all organisations of political thought into groupings, a wide-ranging approach to energy and its governance.

In general, however, and in contrast with the pro-market perspective on energy the geopolitical perspective is defined here as emphasising the geographically fixed and finite nature of natural resources, in particular, and tends to associate possession of resources with power and influence (Venn 1986; Gilpin 1987; Hadfield 2007 and 2008; Klare 2008a). Partly as a consequence of this and the associated importance of being able to access energy, the role of state sovereignty in energy governance is stressed, as are international energy relations and foreign policy.

Historically, energy has been understood through geopolitical lenses more as a national or strategic asset which states must be able to access for the maintenance of modern life or, as one analyst defined it, as the ‘lifeblood’ of modern economies (Gault 2004: 182; cf. Yamani and Ahmad 1981: 66). Other analysts have emphasised the importance of energy within diplomacy and international relations. Fiona Venn in her historical account of oil observes that ‘the history of oil and the history of international relations’ are intrinsically linked (Venn 1986: 1). Such analyses contrast clearly with pro-market analyses that emphasise the fungible nature of natural resources as traded commodities within an economically and positively interdependent world.

Emphasis within this analytical group has been placed on the role of the state in ensuring energy supply security, on strategic, often bilateral alliances, on the search for ‘exclusive backyards’ and on the use of military power to protect supplies (Youngs 2009: 8). Energy security has therefore been considered as a question for state-level politics and associated arrangements (Goldthau 2011: 129). Analyses of energy’s past, particularly oil’s, often refer to military conflicts between nations exacerbated by the perceived need to access oil on acceptable economic and political terms (Venn 1986; Bromley 1991; Painter 1997; Clarke 2007). A reading of geopolitically informed energy literature offers up some pointers as to why energy, as an area of international negotiation, has remained remarkably free of agreement let alone global governance ‘norms’ over the last century (McGowan 2008; Natorski and Surralles 2008).1

This line of thinking ties in with recent foreign policy analysis that concluded that in the energy sector ‘the state has been more resilient than anticipated’ (Hadfield 2007: 33). This is despite the period of substantial international marketisation that energy has been through. Furthermore, with reference to Keohane and Nye’s earlier observations on energy, the analysis concluded that the global dynamics inherent in a sector like energy are still largely at the mercy of national ‘holders of power’ (Hadfield 2007: 33). Examples of energy politics informed by geopolitics are the recent restrictions placed by Russian, Venezuelan, Bolivian and Kazakhstani governments on foreign investment in national oil and gas industries (cf. Goldthau 2012: 203). China’s development of bilateral energy deals with African and Caspian Basin countries which bypass both international markets and multilateral agreements show a clear recognition of the geography and geopolitics of energy supplies and infrastructures.

Climate perspectives

The market-geopolitics debate, for all that it may still represent quite accurately academic research into energy and its governance, is too narrow to reflect current thinking on energy policy. Analyses focusing on such debates tend to underestimate and underemphasise another way of thinking about energy governance, the climate perspective. This is characterised here as being concerned specifically with how energy policy and governance practices might enable climate change mitigation. This perspective has long presented a critique of pro-market energy governance by repeatedly suggesting policy and governance change, often in the form of greater state intervention in transition, in order to enable the delivery of a more sustainable, low-carbon energy system.

The way in which the climate perspective is characterised here is, perhaps, more artificial than the two previous perspectives. As Steven Bernstein suggests, providing definitions of climate or environmental groups can prove problematic. He has observed that environmental analysts, although they may be pursuing a similar end game in the protection of the planet, often suggest extremely different routes to that same end (Bernstein 2001: 29). Even at the time of the first United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (UNCHE), held in Stockholm in 1972, splits had emerged. These were between environmental scientists and conservationists who understood the earth’s resources to be finite, and therefore argued for limits to growth, and those who were more concerned with economic growth and poverty reduction (Bernstein 2001: 29; cf. Meadows et al. 1972; Tickner 1993). This split is characterised by Joerg Friedrichs as that between the neo-Malthusians, who take the view that limits to growth present an inescapable human predicament, and the Cornucopians, who believe in man’s ingenuity and ability to solve problems with technology and knowledge (Friedrichs 2011: 1; cf. Carter 2001).

Attempts to characterise the climate perspective here need to be conscious of these rifts. By the early 1990s a ‘shift in norms of environmental governance had occurred’ which can be characterised by a general acceptance of ‘liberalization in trade and financ...