eBook - ePub

People's Response to Disasters in the Philippines

Vulnerability, Capacities, and Resilience

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

People's Response to Disasters in the Philippines

Vulnerability, Capacities, and Resilience

About this book

This book provides a critical perspective on people's response to disasters in the Philippines. It draws upon an array of case studies to discuss people's vulnerability, capacities and resilience in facing a wide range of different hazards.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access People's Response to Disasters in the Philippines by J. Gaillard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Looking for the Root Causes of Disasters in the Philippines: Unfolding People’s Vulnerability

The first part of this book provides a critical reflection upon the causes of disasters in the Philippines. It debunks the roles of Nature’s extremes and other usual culprits such as illegal loggers as exemplified in the late 2004 disaster in Eastern Luzon. Drawing on the case of the 1991 eruption and lingering lahars of Mt Pinatubo, it eventually tones down the importance of the perception of the risk associated with natural hazards. Finally, a study of coastal communities in Eastern Samar underscores the importance of considering people’s livelihoods in fully understanding the causes of disasters. Overall, this part of the book situates people’s response to disasters in the context of development and daily life.

Chapter Two

Why Did 1,400 People Die in Late 2004?

This chapter aims to investigate the causes of the disaster that killed about 1,400 people following the onslaught of four consecutive tropical depressions and cyclones between the end of November and the beginning of December 2004 in Eastern Luzon. Unfortunately, similar events have been occurring time and again in other places, including Ormoc in 1991 and Cagayan de Oro in 2011. The chapter argues that the catastrophe does not only lie in the obvious triggering of natural hazards but is rather entangled in deeper socioeconomic and political factors. The study particularly focuses on the three hardest hit municipalities of General Nakar, Infanta, and Real, all located in the province of Quezon. The first two sections provide a background on the study area and late 2004 disaster in Quezon. The third section eventually examines the role of the most evident culprits, that is heavy rainfall and deforestation. The fourth section further investigates the role of population dynamics, poor access to land and resources, and oligarchic exploitation of natural resources. The final section reflects upon the political construct of the disaster.

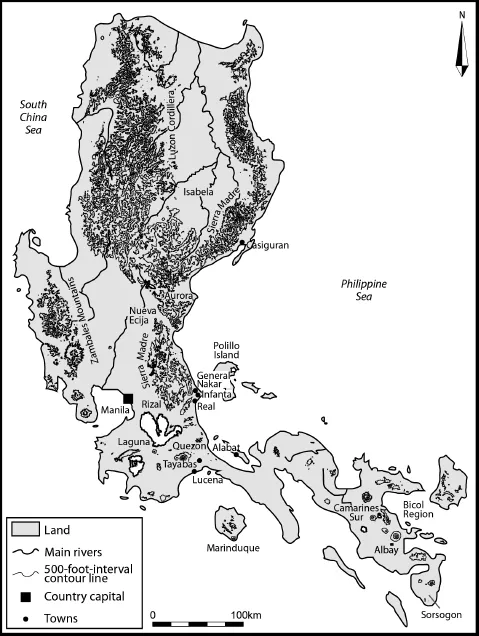

Geographical Setting

The province of Quezon stretches along the Pacific shores of the main island of Luzon (see Figures 1.5 and 2.1). Its topography is characterized by rugged terrain, with the Sierra Madre mountain range running along the length of the province. Lowlands are limited to narrow strips of coastal plains as well as thin river valleys. The climate of Quezon is marked by the absence of a dry season with a very pronounced maximum rainfall from November to January. Cyclones and tropical depressions batter the region between May and December of each year (Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Service Administration, 2005; Wernstedt and Spencer, 1967).

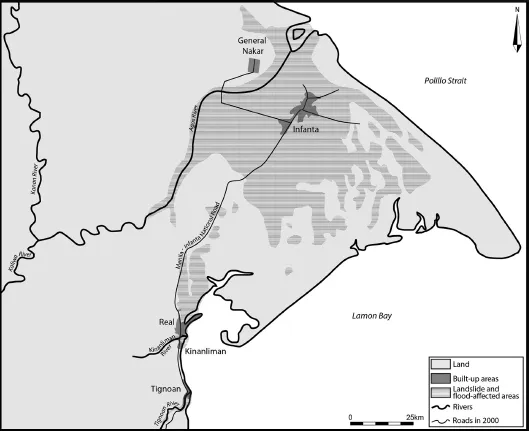

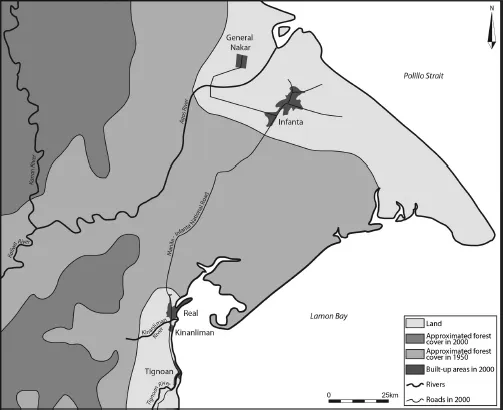

The three municipalities of General Nakar, Infanta, and Real rest on the northern tip of the province (Figure 2.1). Infanta is one of the oldest towns of Quezon, founded in 1578 by Spanish conquistadors. It is nestled within the delta of the Agos River which empties into the Philippine Sea. Floods of large magnitude regularly engulf the Infanta plain and have several times wreaked havoc in the area (Laserna et al., 2005). The last dramatic flooding event before the 2004 disaster occurred in 1986. On the other hand, General Nakar and Real are two younger towns on the northern and southern edges of the mother settlement that broke away from Infanta in 1949 and 1960, respectively, in response to a growing population. On the 1950s topographic maps, both settlements were nucleated around the town proper. However, during the last decades, habitations quickly expanded to the flanks of surroundings hills and mountains. Real further sprawled along the Manila-Infanta road on the steep banks of the Tignoan River.

Figure 2.1 Location of the province of Quezon in Luzon

The 2000 census recorded 50,992 inhabitants in Infanta, 30,684 in Real, and 23,678 in General Nakar (National Statistics Office, 2005). Population density greatly varies from 392 people per km2 in the fertile flood plain of Infanta, 55 people per km2 in Real, to 18 people per km2 in General Nakar. Provincial figures indicate that agriculture (coconut, rice, corn, coffee, vegetables, and livestock), fishing, hunting, and forestry provide income for 39 percent of Quezon’s population. The services sector absorbs 44.5 percent of the population, half of which are based in Lucena, the province’s capital located at the southernmost tip of Quezon (National Statistical Coordination Board, 2004). Nonetheless, there are emerging areas of urbanization. Infanta is notably one of the municipalities that have been identified as such, based on its increasing number of industrial and service activities. Yet, a large fraction of the population still lives below the poverty level set for the country. According to the National Statistical Coordination Board (2005), poverty incidence is pegged at 40.7 percent of the population of Quezon versus 34 percent at the national scale.

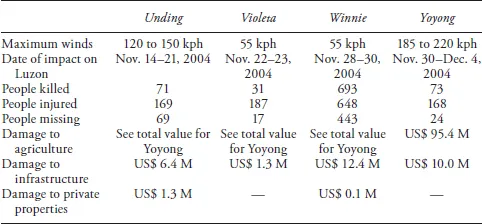

The Late-2004 Cyclone Disaster in Eastern Luzon

Between November 14 and December 4, 2004, four successive tropical depressions and cyclones lashed Eastern Luzon and brought heavy damage and human losses to Quezon as well as to the neighboring provinces of Aurora and Nueva Ecija. The first cyclone to hit Quezon was Unding, between November 14 and 21, 2004. It was immediately followed by tropical depression Violeta, which struck Luzon on November 22 and 23. Five days later, on November 28, tropical depression Winnie slammed into the Philippines. Finally, on November 30, cyclone Yoyong came and devastated the Northeastern quarter of the country (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 Characteristics and impact of the late-2004 cyclones and tropical depressions in Eastern Luzon, Philippines (data from PAGASA and NDCC)

Winnie was unmistakably the event that brought about the most damage. It was considered as one of the strongest tropical depressions of the year to hit the eastern portion of northern Quezon especially General Nakar, Infanta, and Real. Winnie had a maximum center wind of more than 100 km per hour with continuous heavy rainfall, lasting three days. On November 29, the rainfall was so intense that it progressively caused the Agos River, the main drainage system in the north, to overflow slightly. Simultaneously, numerous massive landslides and debris flows occurred upland. Geologists (Laserna et al., 2005) supposed that around 7:00 or 8:00 pm landslide-dams occurred along the Kanan and Kaliwa rivers, two major upstream tributaries of the Agos River (see Figure 2.2). Those dams suddenly broke around 9:00 pm and released a huge amount of floodwater. It carried a large quantity of logs and uprooted tree trunks that cascaded down the Agos River but clogged it below the Infanta—General Nakar bridge forcing a massive overflow toward abandoned channels of the floodplain (see Figure 2.2). Floods eventually reached General Nakar and Infanta around 9:30 pm and submerged the town proper and the surrounding villages in three to four meters of water within 25 minutes. Taken by surprise without any warning, most of the those affected had no choice but to climb onto the roof tops of their houses where most of them spent several hours or days. Floodwater did not recede immediately and the logs floating everywhere amidst all the mud, rocks, and debris created a picture of utmost desolation. More than 200 people in Infanta perished, swept away by the floods, alongside their livelihoods, including their home and possessions. Churches, school buildings, and houses, among other structures, were steeped in muddy waters, while bridges had collapsed and roads had been washed out. Irrigation facilities were destroyed. In the first few days since Winnie’s onslaught, telephone lines were also cut, and access to food, power, and clean water was strictly limited. In General Nakar, around 100 people perished from the floodwater of the Agos River.

Many massive landslides also occurred around the town of Real (see Figure 2.2). Some fed the raging waters of the Kinanliman-Kiloron River with huge amounts of mud, logs, uprooted trees, and boulders, which scrambled down to the villages downstream, killing 26 people and carrying away the Kinanliman Bridge on the Manila–Infanta national road. Intense rainfall also triggered landslides along the Tignoan River and loaded it with a great quantity of debris. Landslides and floodwaters eventually engulfed the village of Tignoan located at the mouth of the Tignoan River and buried alive more than 140 people inside a single building (see Figure 2.2). Almost 250 other inhabitants in surrounding villages of Real were killed or counted missing due to similar flood and landslide events.

Figure 2.2 Geographic setting and areas affected by floods and landslides in the municipalities of General Nakar, Infanta, and Real in Quezon (data from UNOSAT and the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority)

The overall human toll of the disaster for Eastern Luzon mentions 868 people killed while 553 more individuals remain missing (see Table 2.1). The four tropical depressions and cyclones destroyed an estimated US$ 50 million worth of paddies, corn, coconuts, and other high-value commercial crops in the devastated areas. Experts calculated that the effects reduced the nation’s Gross Domestic Product by at least 0.35 percentage point (Virola, 2004). Data from the National Disaster Coordinating Council indicate that 5,087 houses, 1,638 houses, and 3,116 houses were destroyed in Infanta, Real, and General Nakar, respectively. Infanta was the hardest hit by the tragedy, with 12,007 families affected. In Real, 1,067 families were affected, and in General Nakar, 5,786. The environmental impact of the disaster was also huge (Kelly, 2005).

The Evident Culprits: Rainfall and Deforestation

Immediately after the event, the media, politicians, relief workers, and some scientists were very prompt at pinpointing what they called the causes of the disaster: heavy and persistent rainfall associated with the four successive tropical depressions and cyclones on deforested mountain slopes, the combination of which gave way to the devastating landslides (e.g., Cruz, 2005; Kelly, 2005; Office of the Press Secretary, 2004a).

Cyclones and tropical depressions are not rare phenomena on the eastern coast of the province of Quezon, especially in the General Nakar–Infanta–Real area. An estimated average number of 12 cyclones every 20 years hit the region (Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Service Administration, 2005). This figure excludes the more frequent tropical depressions that also regularly visit Luzon and wreak heavy damages. The intensity of the tropical depressions and cyclones is also often higher in the Quezon area than on the western coast of Luzon (Brown, Amadore, and Torrente, 1991).

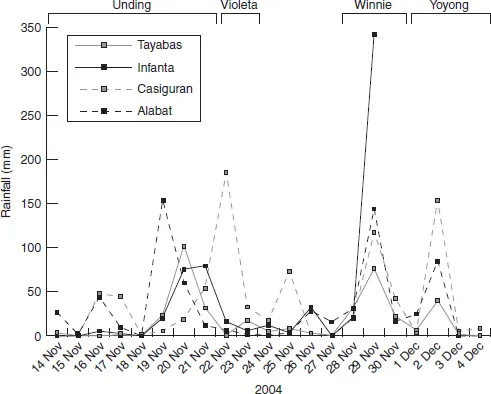

Climatic data from the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical and Astronomical Service Administration (PAGASA) indicate that, compared to other weather stations on the northeastern coast of Luzon (notably Alabat, Tayabas, and Casiguran), rainfall between November 1 and 28, 2004 (432.5 mm) was actually much lower than the last 30-year mean value for the month of November in the town of Infanta (611.8 mm). Cyclone Unding and tropical depression Violeta, therefore, did not bring heavy rain to the General Nakar–Infanta–Real area. It was only on November 29 that the amount of rain that fell was indeed exceptional (see Figure 2.3). Rainfall data indicate that in Infanta, rain amounted to 342 mm within six hours, between 2:00 pm and 8:00 pm before raging flood waters destroyed the local weather station. It is therefore not the alleged accumulation of strong rainy episodes which triggered the floods and landslides in Infanta, General Nakar, and Real but a single event of exceptionally heavy rainfall. Moreover, Laserna et al. (2005) indicate that comparable or even much bigger flooding episodes had occurred in the past as shown by buried logs that have been recovered at a depth of 1.5 m in an area of General Nakar not struck by the late-2004 floods.

Figure 2.3 Daily rainfall for Infanta and other neighboring meteorological stations from November 14 to December 4, 2004 (data from the Philippine Atmospheric, Geophysical, and Astronomical Service Administration)

The situation was deeply aggravated by the rugged terrain overlooking the three towns of Real, Infanta, and General Nakar. As it were, the landslide areas were deeply dissected, with precipitous slopes. The geological survey conducted immediately after the events mentioned that “this heavy rainfall saturated the ground and caused the excessive surface run-off that found its way into the valleys and slopes. The over-saturation of the soil cover caused it to liquefy that in turn resulted into massive landslides and debris fall” (Laserna et al., 2005: 6–7).

The magnitude of the landslides and floods was greatly exacerbated by the paucity of trees to hold the soil. Thousands of logs were washed down the slopes of the mountains and brought to the seashore (see Figure 2.4), leaving heavy damages along their path. Figure 2.5 shows that the decrease in forest cover around General Nakar, Infanta, and Real was drastic between 1950 and 2000. The entire deltaic plain of Infanta and most of the foothills of its surrounding mountains have been deforested. Such massive timber cutting cannot be attributed to swidden agriculture but to commercial logging, both legal and illegal (Kummer, 1992). Commercial logging in General Nakar, Infanta, and Real has been primarily driven by the presence of a vast pristine forest rich in highly valuable dipterocarp species. From the 1960s to the 1970s, several logging concessions legally operated in Quezon and the neighboring province of Aurora, formerly part of Quezon. A series of logging bans in the 1980s and 1990s limited legal timber cutting activities to small-scale, community-based cutting of trees called Integrated Forest Management Agreements (IFMA) projects that have been piloted by the government together with the private sector. At this time, Quezon seems to have become a hub of illegal logging (Kummer, 1992), which contributed to the largest decrease in forest cover in the General Nakar, Infanta, and Real area.

Figure 2.4 Logs deposited by floodwaters in Infanta (photograph by JC Gaillard, June 2005)

Figure 2.5 Approximated decrease in forest cover around General Nakar, Real, and Infanta between 1950 and 2000 (data from Environmental Science for Social Change, the National Mapping and Resource Information Authority and the Department of Environment and Natural Resources)

Undeniably, heavy rainfall on deforested steep slopes on November 29, 2004, resulted in the devastating floods and landslides that str...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- One Introduction

- Part I Looking for the Root Causes of Disasters in the Philippines: Unfolding People’s Vulnerability

- Part II No One Is a Helpless Victim! People’s Capacities to Face Hazards and Disasters

- Part III From Disaster to Development? People’s Resilience in the Aftermath of Disaster

- Bibliography

- Index