eBook - ePub

The Decentralized Energy Revolution

Business Strategies for a New Paradigm

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The global energy system stands at the verge of a far-reaching paradigm shift. The established model of centralized supply services will be challenged by new, decentralized technologies, with Germany being an international role model for energy efficiency and renewable energy generation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Decentralized Energy Revolution by C. Burger,J. Weinmann in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Empowerment Paradigm – The Age of the Prosumer

The history of humankind is inextricably intertwined with the usage of energy. As much as human development was characterized by slow adaptation processes and sudden social or cultural revolutions, the shifts in energy use can also be interpreted as periods of slowly evolving, incremental progress and abrupt – and often radical – changes. Since the very beginning of cultural organization, human beings used manual force, mechanical tools, and the power of domesticated animals to make their labors easier and create an ever-increasing quality of life. While the taming of fire facilitated the use of fuel wood, peat, and dung for cooking and heating, very early civilizations already knew how to extract energy from water and wind. The sun served for drying food and producing salt.

Biomass – and later also charcoal produced from biomass – remained the single most important source of energy for most of our history. With the demographic growth from the 16th and 17th centuries onwards, the depletion of forestry reserves and the rise of the steam engine during the industrial revolution required – in particular in Europe – a reorientation in the use of energy sources; coal – with a much higher energy output per unit mass than wood or charcoal – incrementally replaced timber as the most important energy source for human beings, reaching a first peak in the first half of the 20th century. Meanwhile, oil extraction became technically feasible, and with the rise of individual vehicle transport, oil replaced coal as the predominant form of energy after the 1950s. The usage of natural gas, albeit technically more demanding because of its grid character, also began on a larger scale in the second half of the past century. While hydroelectric power has had a minor but not unimportant role in electricity generation since the late 19th century, the emergence and usage of nuclear fission proved to be the last major new entry among the top primary energy sources.

Today, a new transformation is about to take place: Climate change and the threat of global warming, as well as finite fossil resources, require that societies step back from carbon dioxide-intensive forms of energy (for a thorough discussion, see Gore, 2009). A growing public skepticism toward nuclear power prevents this largely carbon-free technology to substitute fossil fuels on a large scale. Humankind seems to be on the way to returning to a larger share of renewable, non-polluting sources of energy.

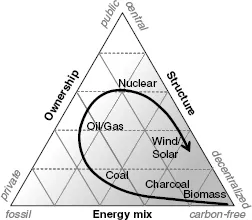

The cyclicality in the energy supply mix is paralleled by similar developments in the balance between central and decentralized energy generation. While early civilizations collected fuel wood and produced charcoal in a local setting, the industrial revolution led to larger power plants for manufacturing and electricity provision. In the 20th century, economies of scale reached their peak with the introduction of nuclear power plants and large hydropower dams. But with liberalization, smaller combined cycle gas power plants became attractive because of their standardized design, lower investment costs, and high efficiency. The move to small-scale supply structures was accelerated by advances in photovoltaic panels, solar thermal heating, and wind turbines.

Meanwhile, the ownership structure of assets in the energy sector shows the same pattern: From dispersed ownership of the first energy-harvesting installations to publicly owned utilities in many countries during the 20th century, and back to private investors after liberalization. In Germany, more than half of the capacity of renewable energies is owned by private persons and farmers. Figure 1.1 shows how the energy system trajectory may eventually return to its starting point with a decentralized, carbon-free and privately owned energy supply system.

Figure 1.1 Energy system trajectory

However, renewable energies have their drawbacks. First, as compared to fossil fuels, their energy yields are often low, and harvesting them requires sophisticated, expensive technologies. Second, their availability typically fluctuates over time and varies according to geography and climate. The dispersed settings pose a major challenge because the energy supply structure has to move back from a system with power plants based on fossil resources that start operating upon request to a structure that absorbs energy where and when it becomes available, often without the convenience of being able to store larger amounts of energy over time.

While early human civilizations consumed energy in modest amounts – both per capita and in total – the fundamental challenge of the return to decentralized, renewable energy supply is how to satisfy the energy needs of 7 billion people or more without sacrificing the generally high quality of life of people in industrialized nations or without jeopardizing the prospect of reaching the same quality of life in developing and emerging countries.

This challenge requires a fundamental, far-reaching change in the supply patterns and can be seen as a paradigm shift. Following Markard and Truffer (2006, 611), we define paradigm, in this context, as a “prevailing model for the solution of techno-economic problems.” Paradigm shifts in large technical systems occur less frequently than in other fields of industrial activity because the technical interdependencies of system components, their standards, institutions, and routines create a high degree of path-dependency on the overall configuration of the system, in particular in grid-based energy services.

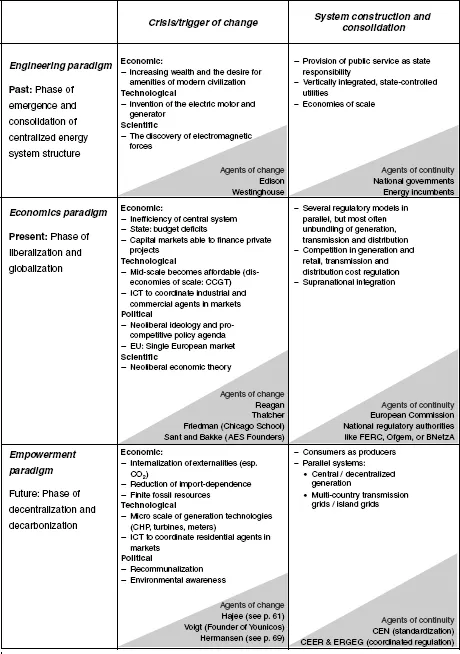

In the electricity sector, a sequence of three paradigms can be postulated, which we call “engineering paradigm” for the early stage of energy services, “economics paradigm” for the epoch since the liberalization of the sector, and “empowerment paradigm” for the decentralized energy supply of the future.

The first phase – the engineering paradigm – was characterized by competing technologies closely linked to individual entrepreneurs. Thomas Alva Edison developed a long-lasting light bulb in 1879 and established the first direct current (DC) electric power distribution system in 1882, which supplied street lamps and private houses with electricity – in total 59 customers. His business model spread across cities in the United States within a decade, and he formed the Edison General Electric Company. However, one of the main disadvantages of the DC technology was that the current could not be transported farther than around three miles without major losses, so there were decoupled, independent patches with autonomous electricity provision.

Meanwhile, another US entrepreneur, George Westinghouse, developed a commercial application of Nikola Tesla’s alternating current (AC) transmission system and installed the first commercial AC power system in 1891 in the US mountain resort of Telluride, Colorado. Westinghouse and Edison entered the so-called War of Currents, in which each propagated his system as being superior. Edison pointed to the dangers of alternating current and campaigned against his competitor by electrocuting animals, including the by-then famous Topsy the Elephant. Ultimately, Edison’s efforts did not pay off. In 1893, Westinghouse won the competition to provide electricity for the World’s Fair in Chicago and was selected to construct the generators for the hydroelectric power plant at Niagara Falls, USA. The AC technology eventually became the US standard. At the turn of the century, electricity had reached all industrialized countries and drastically altered public and private life, transportation, and industry.

After the First World War, governments started to strive for standardization and control of the electricity system, with the aim of establishing integrated, large-scale grid supply structures within their respective countries. By the late 1930s, much of the formerly privately owned and locally organized firms were absorbed by the overarching, domestic transmission networks, most often vertically integrated and with a strict tariff control based on rate-of-return regulation. With the emergence of electric devices like vacuum cleaners, refrigerators, and washing machines, electricity moved from being an integrated service like lighting to a basic infrastructure requirement for multiple appliances.

The electricity system under the engineering paradigm proved to be fairly stable and reliable. However, a number of influential scholars, in particular Noble prize winner Milton Friedman and his peers at the Chicago School of Economics, heralded the economics paradigm, when they expressed general skepticism about too heavy involvement of the state in the economy. Their view spilled over into the Western political elite in the 1980s. US president Ronald Reagan and UK prime minister Margaret Thatcher started to introduce competition in state-controlled infrastructure services, state assets were privatized, and financial institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund coupled free-market policy directives with their structural adjustment loans for developing countries (Stiglitz, 2002). In continental Europe, the European Commission became a key proponent of liberalization because the concept closely matched the vision of a single European market across all member states.

Electricity became a commodity. Liberalization reallocated ownership, dismantled vertically integrated utilities, reshuffled control rights, and introduced market elements such as wholesale spot trading and retail competition. A range of new market players entered the sector with innovative strategies, such as Roger W. Sant and Dennis W. Bakke, the founders of AES, which became one of the first firms to see and exploit the full potential of liberalized markets in the United States. Meanwhile, incumbent utilities were deprived of secure revenue streams and had to reconfigure their traditional business models.

The liberalization of grid-based services was a top-down regulatory change, which also had consequences for the technologies deployed. In particular, gas-fired, combined-cycle turbines became the preferred choice for investments in generation capacity (Markard and Truffer, 2006, 616). Due to the economics of series production, a high degree of standardization in the construction of power plants – and their economic and energetic efficiency – they altered the power plant mix of many countries, for example the United Kingdom and the United States. Simultaneously, advances in information and communication technologies (ICTs) allowed for the participation of many industrial and commercial players in wholesale and retail markets.

Public funding of renewable energies, in particular wind and solar power, triggered the beginning of the empowerment paradigm. The subsidies succeeded in attracting a multitude of private investors – often on the community and even household levels – to install photovoltaic panels or wind parks. This had major consequences for the transition to a sustainable energy supply structure, but also created substantial challenges to grid stability and the coordination of loads and energy flows. Closely connected to the deployment of renewable energies, decentralized energy solutions beyond wind and solar emerge as parallel features of the energy system. Compared to the top-down changes of liberalization and renewable energy subsidy schemes, the move toward a decentralized energy supply is more complex in its forces, as we will outline in the next sections.

Once a new paradigm has been established, a period of upheaval is followed by consolidation and continuity. Institutions are created that provide the administrative framework, ensure legal compliance, and maintain the status quo. While the early phase of electrification was characterized by entrepreneurial activities, in the early 20th century national governments took over and defined electricity supply as a core infrastructure and part of the public service obligation that the state had to take care of. The transition to the economics paradigm was accompanied by legislative changes such as the Purpa Act in the United States or the Lisbon Treaty in the EU. The responsibilities for regulating and monitoring the market once it was established were taken over by institutions like the European Commission and national regulatory agencies with formal independence from their respective governments. In the EU, the regulators have since then coordinated and advanced the market design under the existing status quo.

Table 1.1, on the following page, sketches the sequence of three paradigms with its main agents and institutions.

We have identified three key drivers for the transition to the new paradigm: Technologies, regulation, and empowerment.

Technological drivers

A decentralized energy supply relies on a multitude of individual technologies. Some of them have already been on the market for several decades but have not left their niches, such as heat pumps and micro CHP units. It is only now that industrial mass production has created the necessary economies of scale to reduce investment costs. As one example, we will present the procedures that Volkswagen has introduced to turn the manufacturing of micro CHP units into a venture that utilizes the mechanisms and routines that the company employs to produce cars. Similarly, batteries for power storage have experienced steep cost degressions over the past couple of years, and will become much less expensive in the near future because improvements in battery technology for electric vehicles will create significant spillover effects, especially to stationary applications.

Table 1.1 Paradigm shifts in the electricity sector

Most importantly, information and communication technologies have progressed at an impressive pace over the past decade. The decentralized energy revolution would not be possible without the digital revolution. ICTs allow for the instantaneous coordination of multiple agents in a large technical system. The current grid structure will have a “smart” layer added on top that will transmit all system states and provide the basis for largely autonomous island systems.

The combination of new energy technologies with new ways of communicating may even trigger a “third industrial revolution,” as Jeremy Rifkin suggests:

In my explorations, I came to realize that the great economic revolutions in history occur when new communication technologies converge with new energy systems. New energy regimes make possible the creation of more interdependent economic activity and expanded commercial exchange as well as facilitate more dense and inclusive social relationships. The accompanying communication revolutions become the means to organize and manage the new temporal and spatial dynamics that arise from new energy systems. (2011, 2)

The parallel development of new communication and energy technologies is a necessary but not sufficient condition for initiating a paradigm shift, though. It requires the market, hence the consumers, to accept and buy new products. Smart meters or electric vehicles are prime examples that new technologies are available but that they may not be adopted unless regulatory incentives are introduced.

Regulatory drivers

Energy supply is part of the core infrastructure services, for which the government bears ultimate responsibility. Even in liberalized markets, a total withdrawal of the state from the sector is practically impossible. The foresight of political decision-makers and regulatory agencies is supposed to correct for market failures, in particular negative externalities due to climate change and security of supply.

Decentralized energy generation has the advantage that many of the technologies are less carbon-intensive and more efficient than conventional energy production. In particular, the efficiency of cogeneration, that is, the coordinated production of heat and electricity in a single plant, exceeds the production of heat and power in individual plants by far. Similarly, increasing the efficiency of the housing stock often provides a least-cost option to save tons of carbon dioxide while reducing the energy bill of homeowners.

In addition to measures that mitigate climate change, decentralized energy generation increases energy autarky. The use of local biomass, wind power, or geothermal energy, including heat pumps, reduces the requirement to import fossil fuels. Given the finite amount of all fossil reserves and growth in global demand, rising prices are likely to be observe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction: Decentralized Energy as a Disruptive Innovation

- 1 Empowerment Paradigm The Age of the Prosumer

- 2 Small Is Beautiful

- 3 The Rise of Island Systems

- 4 Smart Management of Electricity and Information

- 5 Local Storage Solutions

- 6 Enabling Negawatts

- 7 Insights from Germany for a Decentralized Energy Future

- Appendix: Company and Interviewee Profiles

- Notes

- References

- Key concepts, persons and technologies