eBook - ePub

The Battle for the Roads of Britain

Police, Motorists and the Law, c.1890s to 1970s

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Battle for the Roads of Britain

Police, Motorists and the Law, c.1890s to 1970s

About this book

Policing in Britain was changed fundamentally by the rapid emergence of the automobile at the beginning of the twentieth century. This book seeks to examine how the police reacted to this challenge and moved to segregate the motorist from the pedestrian in an attempt to eliminate the 'road holocaust' that ensued.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Battle for the Roads of Britain by David Taylor,Keith Laybourn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & British History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Challenge of Automobility and the Response of Policing in Britain: An Overview of a New Vista

The ‘new form of express train’

The automobile brought about seismic changes in every developed country in the world by rapidly replacing horsedrawn vehicles as the predominant form of transport in the early decades of the twentieth century. The exponential growth of motorised vehicles across the world, from a few thousand in the late 1890s to one million in 1910, 50 million in 1930s, 100 million in 1955, 500 million in 1985 and to more than 1 billion by 2010, has exerted profound social, economic, political and environmental impact upon societies and fundamentally changed the way in which many of them have operated.1 The private ownership of cars, in particular, has been central to the personal autonomy of the majority of people. It has become the basis of transport, overtaking the train and other forms of transport, and a desired possession that provides status. Yet almost immediately they appeared, motor vehicles posed major problems for society and have done so ever since, whether as a cause of social discrimination, death, injury, congestion, gridlock and environmental pollution in what has become a battle for the roads between motorists and pedestrians in which the emergence of trunk roads and motorway can be seen as the triumph of the motorists. Ever-increasing numbers of motor vehicles were forced to jostle alongside horsedrawn traffic, trams, hand-pulled barrows and carts, with dramatic social consequences.

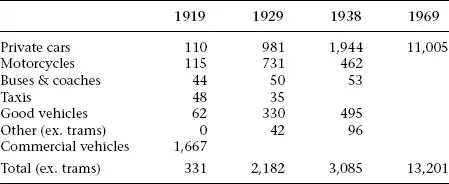

The ubiquitous problem has been road accidents involving motorised vehicles. Even in the 1930s, when there were relatively few such vehicles on the road, the death and injury figures for accidents were horrifically high and referred to as the ‘road holocaust’. In the United States (with a population of about 135 millions), road accidents caused 39,700 deaths and 895,280 injuries in 1937. In Germany (with a population of 69 millions), 8,509 were killed and 171,120 were injured between the beginning of 1935 and the beginning of 1936. In France (with a population of 42 millions) there were 4,415 road deaths in 1935, though the number of injuries went unrecorded. In 1937, a relatively good year for road accidents in the 1930s, there were 6,561 deaths on Britain’s roads and 227,813 injuries, at a time when the population was only about 46 millions.2 Road deaths in Britain had exceeded 7,000 annually in the years 1930, 1933 and 1934.3 These figures rose again during the Second World War to 8,264 in 1939, 8,609 in 1940 and 9,169 in 1941 according to Home Office files (7,136, 7,359 and 7,578 for England and Wales), although thereafter they fell as a result of the dramatic reduction in car ownership in late wartime Britain before there was a second ‘road holocaust’ in the 1950s and early 1960s.4 These were truly alarming figures in a day and age when motorised transport was still in its infancy. Indeed, at the end of the 1930s Britain had only about three million motorised motor vehicles, two million of them cars (alongside about 426,000 motorcycles), compared with more about 34 million motor vehicles in 2013 (Table 1.1), and the road casualties (Table 1.2) were frighteningly high in relation to the number of vehicles. The situation has improved significantly since then, and there were only 1,300 deaths and 186,000 injuries in 2013 – though much of the recent improvement in road fatalities occurred between 2009 and 2013, with a decline of more than 40 per cent.5

Table 1.1 Motor vehicles in use in Britain, 1919–1966 (000s)

Source: B. R. Mitchell and P. Deane (1962), Abstract of British Historical Statistics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), p. 20; MT 92/226, from an article in Justice of Peace and Local Government, 27 January 1968, for the statistics for 1966. Also W. Plowden (1971), The Motor Car and Politics 1896–1970 (London: Bodley Head), pp. 456–457 suggests that there were 16,000 motor vehicles in 1905; 143,877 by 1910; 650,148 in 1920; and 2,273,661 in 1930.

Table 1.2 Deaths and injuries on Britain’s roads, 1919–20126

Year | Deaths | Injuries |

1919 | 1,000 (est.) | |

1921 | 2,673 | |

1926 | 4,886 | 134,000 (rounded) |

1927 | 5,329 | 149,000 |

1928 | 6,138 | 165,000 |

1929 | 6,696 | 171,000 |

1930 | 7,305 | 177,855 |

1931 | 6,691 | 202,895 |

1932 | 6,667 | 206,450 |

1933 | 7,202 | 216,000 |

1934 | 7,343 | 232,000 |

1935 | 6,502 | 222,000 |

1936 | 6,561 | 228,000 |

1937 | 6,633 | 226,000 |

1938 | 6,648 | 227,000 |

1939 | 8,272 | |

1940 | 8,609 | |

1941 | 9,169 | |

1942 | 6,926 | 141,000 |

1943 | 5,796 | 117,000 |

1944 | 6,416 | 124,000 |

1945 | 5,256 | 133,000 |

1946 | 5,062 | 157,000 |

1947 | 4,881 | 161,000 |

1948 | 4,513 | 149,000 |

1949 | 4,773 | 172,000 |

1950 | 5,012 | 196,000 |

1951 | 5,250 | 211,000 |

1952 | 4,706 | 203,000 |

1953 | 5,090 | 222,000 |

1954 | 5,010 | 233,000 |

1955 | 5,526 | 262,000 |

1956 | 5,367 | 263,000 |

1957 | 5,550 | 268,000 |

1958 | 5,970 | 294,000 |

1959 | 6,520 | 327,000 |

1960 | 6,970 | 341,000 |

1961 | 6,908 | 343,000 |

1962 | 6,709 | 335,000 |

1963 | 6,992 | 349,000 |

1964 | 7,820 | 378,000 |

1965 | 7,952 | 390,000 |

1966 | 7,985 | 384,000 |

1967 | 7,319 | 363,000 |

1968 | 6,810 | 342,000 |

1969 | 7,365 | 346,000 |

1970 | 7,499 | 356,000 |

1980 | 6,010 | 323,000 |

1990 | 5,217 | 336,000 |

2000 | 3,409 | 317,000 |

2010 | 1,850 | 202,000 |

2012 | 1,754 | 193,699 |

The age of the car had arrived in Britain by the early twentieth century, with manifest and frightening social consequences for society. Lord Alness, whilst chairing a Select Committee of the House of Lords on Road Accidents (hereafter the Alness Committee) on 10 May 1938, suggested to C. T. Foley, of the Pedestrians’ Association, that ‘the community as a whole has not yet fully realised the truly revolutionary character of the changes in the condition of road traffic to-day’.7 Foley replied that:

Our President, Lord Cecil [of Chelwood], put the position, I think, in a very apt way when he said that when the motor car was introduced it was considered to be nothing more than an improved form or horse vehicle or a horseless carriage, whereas in point of fact it has turned out to be a new form of express train running the public highway without the safeguards which express trains on line are necessarily subject to.8

This was evident in his further comments about the need for the construction of footways and bridges which, he felt, ‘would only confirm the view of the motorist that the public highway was a motor speed track and would lead to further accidents’.9 Indeed, the motorised vehicle was to fundamentally change relations between competing road users and to produce increased zoning on the highways of Britain between the 1920s and the 1970s; it was, in fact, to dominate the highway.

This is not to suggest that the nineteenth-century horsedrawn world of transport was without its obvious dangers. By the 1840s there may have been as many as 1,000 deaths per year on Britain’s roads, though accurate figures were not gathered by the Registrar General until 1863. These were caused mainly by horses and horsedrawn vehicles, and rose in the 1850s and 1860s before declining (though only relative to population growth) by the end of the century.10 Indicative of the continuing scale of danger presented by horses and horsedrawn vehicles at the beginning of the twentieth century is the fact that 84 police officers received medals, thanks, or money, for their action in capturing dangerous loose horses in the City of Liverpool in 1907.11 Indeed, pedestrians throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries faced serious dangers from other road users in crossing carriageways and walking on ill-defined and ill-constructed pavements and required the help of the police whose duties for traffic control had been laid down by the Police Act of 1839. James Monro, Metropolitan Police Commissioner, observed in 1889 that ‘few crossings in crowded thoroughfares can be got over by the nervous and the timid without the appeal for the courteous help of the policeman’.12

Nonetheless, pedestrians and horse transport had almost exclusive rights to the highway in the early and mid-nineteenth century but competed with municipal trams and cyclists from the 1880s and motorcycles and cars at the turn of the century. Such conflicts could be accommodated in the nineteenth century, largely because little traffic travelled at significant speed on British roads. This was no longer the case from the early twentieth century because of the rising speeds of vehicles on the road. Pedestrians moved at 3 or 4 mph, horsedrawn traffic at four or five miles per hour, ‘hurtling cyclists’ at eight to ten mph, and cars at 12 or 14 mph (although their speeds were soon to achieve 30–60 mph). As cars improved travelling time became concentrated in new age of speed to effectively deny pedestrians their historic freedom of the highway. The ‘road holocaust’ of the 1930s was largely the result of motorised vehicles that had transformed the speed of the road.

Speeding automobiles mowing down pedestrians were seen to be an alarming and significant cause of the high death and injury figures in Britain from the beginning of the twentieth century. This led to the widespread use of the military metaphors of ‘battle’ and ‘war’ in connection with the roads by the press, all road users and the police. ‘Candide’, almost certainly a policeman, wrote an article for the Police Review in 1957 entitled ‘The Battle for Britain’s Roads’, arguing that ‘the roads of Britain remain battlefields, with the all-too familiar list of dead and mourned, impaired health and wasted property ever present, while apathy grows in the shade of unnecessary statistics.’13 To him the battle was made worse by the under-resourcing and fragmenting of responsibility which held back road safety with ‘Jacob Marley’ chains. This conflict between road users fermented into a spate of legislation to control the speed of cars and lorries and maintain road safety, which inevitably produced a bewildering and multiplying array of traffic offences. This inevitably promoted the growth of pressure groups to represent all those with an interest in the use of the road, including the police who were entrusted to enforce the law.

Policing and traffic policing in Britain in the early twentieth century

Before examining the work of traffic policing per se it is helpful to understand its developments in in relation to the structure of policing in Britain in the early twentieth century. Where, indeed, did it fit into the pattern of policing and what problems did it face? After the First World War, when the number of motorised vehicles increased rapidly, there were about 230 police forces in Britain (though the numbers fell during the inter-war years and rapidly after the Second World War), and 58 county forces and 128 borough forces in England and Wales alone in 1918.14 They were directly responsible to their joint standing committees (counties) and their local watch committees (borough forces) but partly financed by the Treasury as a result of the County and Borough Police Act of 1856, which offered a 25 per cent Treasury grant towards pay and clothing. This at least imposed some type of uniformity through the need of the forces to obtain a Certificate of Efficiency each year following an annual inspection t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1. The Challenge of Automobility and the Response of Policing in Britain: An Overview of a New Vista

- 2. Historiography and Argument

- Part I: Policing Britain c.1900–1970: Enforcing the Law on the Motorist

- Part II: Engineering, Educating and Channelling Road Safety

- Conclusion

- Appendices

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index