- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book focuses on all major aspects of the asset management industry including its regulations, strategies, processes, applied technologies and risks. It provides a serious resource for readers seeking greater depth and alternative opinions on specific industry developments, and breadth for specialists interested in the dynamics of the industry.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Global Asset Management by M. Pinedo, I. Walter, M. Pinedo,I. Walter in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Accounting. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Global Asset Management – Introduction and Overview

1

The Asset Management Industry Dynamics of Growth, Structure and Performance

Ingo Walter

1.1 Introduction

This chapter examines the industrial organisation and institutional development of the global asset management industry. Few industries have encountered as much ‘strategic turbulence’ in recent years as has the financial services sector in general and the asset management – the ‘buy-side’ of the capital markets – in particular. Indeed, there is ample evidence to suggest that the development of the asset management industry has much to do with capital allocation in national and global financial systems. That is, asset-gathering and deployment of savings affect the pace of capital formation and the economic growth process more broadly.

Consequently, the asset management industry will continue to be one of the largest and most dynamic parts of the global financial services sector, resuming its long-term growth after the impact of the global financial crisis of the 2000s – based on a number of underlying factors:

•A continued broad-based trend toward professional management of discretionary household assets in the form of mutual funds or unit trusts and other types of collective investment vehicles.

•The growing recognition that most government-sponsored pension systems, many of which were created wholly or partially on a pay-as-you-go (PAYG) basis, have become fundamentally untenable under demographic projections that appear virtually certain to materialise, and must be progressively replaced by asset pools that will throw off the kinds of returns necessary to meet the needs of growing numbers of longer living retirees.

•Partial displacement of traditional defined-benefit public- and private sector pension programs backed by assets contributed by employers and working individuals under the pressure of the evolving demographics, rising administrative costs, and shifts in risk-allocation by a variety of defined-contribution schemes.

•Substantial increases in individual wealth in a number of developed countries and a range of developing countries, as reflected in changing global shares in assets under management.

•Reallocation of portfolios that have – for regulatory, tax or institutional reasons – been overweight domestic financial instruments (notably fixed-income securities) toward a greater role for equities and non-domestic asset classes. These not only may provide higher returns but also may reduce the beneficiaries’ exposure to risk due to portfolio diversification across both asset classes and economic and financial environments which are less than perfectly correlated in terms of total investment returns.

•A continued important role for alternative asset classes and special situations in real assets, private equity and certain hedge funds. However, a long period of mediocre performance and a dearth of investment opportunities – together with high fees, compliance problems and operational risks may/will continue to undermine some types of alternative assets going forward.

The chapter reviews the four main components of the asset management industry – pension funds, mutual funds, alternative asset pools such as hedge funds, and private client asset pools. The chapter then discusses key structural and competitive characteristics of the industry and its reconfiguration.

1.2 Mapping the global asset management industry

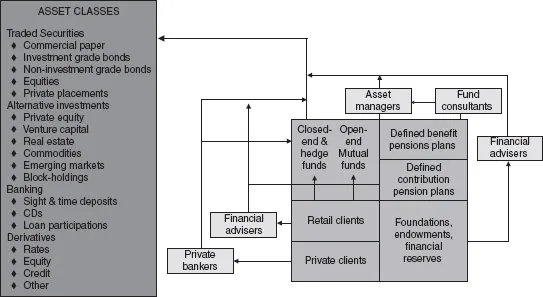

The layout of the global asset management industry can perhaps best be explained in terms of Figure 1.1. The right side of the diagram is the institutional side of the market for professional asset management and the left side is the individual side of the markets, although the distinctions are often heavily blurred.

First, retail clients have the option of placing funds directly with financial institutions such as banks or by purchasing securities from retail sales forces of broker-dealers, possibly with the help of fee-based financial advisers. Alternatively, retail investors can have their funds professionally managed by buying shares in mutual funds or unit trusts (again possibly with the help of advisers), which in turn buy securities from the institutional sales desks of broker-dealers (or maintain balances with banks).

Second, private clients are broken-out as a separate segment of the asset management market in Figure 1.1, and are usually serviced by private bankers who bundle asset management with various other services such as tax planning, estates and trusts, placing assets directly into financial instruments, commingled managed asset pools, or sometimes publicly-available mutual funds and unit trusts.

Figure 1.1 Mapping the global asset management architecture

Third, foundations, endowments, and financial reserves held by nonfinancial companies, institutions and governments can rely on in-house investment expertise to purchase securities directly from the institutional sales desks of banks or securities broker-dealers, use financial advisers to help them build efficient portfolios, or place funds with open-end or closed-end mutual funds.

Fourth, pension funds take two principal forms, those guaranteeing a level of benefits and those aimed at building beneficiary assets from which a pension will be drawn (see below). Defined-benefit pension funds can buy securities directly in the market, or place funds with banks, trust companies or other types of asset managers, often aided by fund consultants who advise pension trustees on performance and asset allocation styles. Defined-contribution pension programs may operate in a similar way if they are managed in-house, creating proprietary asset pools, and in addition (or alternatively) provide participants with the option to purchase shares in publicly-available mutual funds.

The structure of the asset management industry encompasses significant overlaps between the four types of asset pools to the point where they are sometimes difficult to distinguish. We have noted the linkage between defined-contribution pension funds and the mutual fund industry, and the association of the disproportionate growth in the former with the expansion of mutual fund assets under management. There is a similar but perhaps more limited linkage between private client assets and mutual funds, on the one hand, and pension funds, on the other. This is particularly the case for the lower-bound of private client business, which is often commingled with mass-marketed mutual funds, and pension benefits awarded to high-income executives, which in effect become part of the recipient’s high net worth portfolio.

1.3 Pension funds

The pension fund market for asset management has been one of the most rapidly growing domains of the global financial system, and promises to be even more dynamic in the years ahead. Consequently, pension assets have been in the forefront of strategic targeting by all types of financial institutions, including banks, trust companies, broker-dealers, insurance companies, mutual fund companies, and independent asset management firms.

Pension fund assets in the OECD countries reached a record USD 20.1 trillion in 2011 but return on investment fell below zero, with an average negative return of –1.7% due to weak equity markets and low interest rates.1 Roughly two-thirds of the assets covered private sector employees and the balance covered public sector employees. The growth rate of pension assets had been about 5% per year before the global financial crisis, but declined materially during the crisis. About 40% of global pension assets under management are in Europe and the United States, roughly evenly divided, while the rest of the world accounted for the balance – although the most rapidly growing, especially in Asia.

The basis for the projected growth of managed pensions continues to focus on the demographics of gradually aging populations, colliding with existing structures for retirement support which in many countries carry heavy political baggage. They are politically exceedingly difficult to bring up to the standards required for the future, yet doing so eventually is inevitable. The near-term focus of this problem will be Europe and Japan, with profound implications for the size and structure of capital markets, the competitive positioning and performance of financial intermediaries in general and asset managers in particular.

The demographics of the pension fund problem are straightforward, since demographic data are among the most reliable. Unless there are major unforeseen changes in birth rates, death dates or migration rates, the dependency ratio (population over 65 divided by the population age 16–64) will have doubled between 2010 and 2040, with the highest dependency ratios in the case of Europe being attained in Italy, Germany and the Netherlands, and the lowest in Ireland. Japan has dependency ratios even higher than Europe, while the US ratio is somewhat lower – with the lowest generally found in developing countries. Surprisingly close behind are major emerging markets like Korea and China. All are heading in the same direction.

While the demographics underlying these projections may be quite reliable, dependency ratios remain subject to shifts in working age start- and end-points. Obviously, the longer people remain out of the active labour force (e.g., for purposes of education), the higher the level of sustained unemployment; and the earlier the average retirement age, the higher will be the dependency ratio. The collision comes between the demographics and the existing structure of pension finance. There are basically three ways to provide support for the post-retirement segment of the population:

•Pay-as-you-go (PAYG) programs: Pension benefits under this approach are committed by the state based on various formulas – number of years worked and income subject to social charges, for example – and funded by current mandatory contributions of those employed (taxes and social charges) that may or may not be specifically earmarked to covering current pension payouts. Under PAYG systems, current pension contributions may exceed or fall short of current disbursements. In the former case a trust fund may be set up which, as in the case of US Social Security, may be invested in government securities. In the latter case, the deficit will tend to be covered out of general tax revenues, government borrowing, or the liquidation of previously accumulated trust fund assets.

•Defined-benefit programs: Pension benefits under such programs are committed to public or private sector employees by their employers, based on actuarial benefit formulas that are part of the employment contract. Defined-benefit pension payouts may be linked to the cost of living, adjusted for survivorship, etc., and the funds set aside to support future claims may be contributed solely by the employer or with some level of employee contribution. The pool of assets may be invested in a portfolio of debt and equity securities (possibly including the company’s own shares) that are managed in-house or by external fund managers. Depending on the level of contributions and benefit claims, as well as investment performance, defined-benefit plans may be over-funded or under-funded. They may thus be tapped by the employer from time to time for general corporate purposes, or they may have to be topped-up from the employer’s own resources. Defined-benefit plans may be insured (e.g., against corporate bankruptcy) either in the private market or by government agencies, and are usually subject to strict regulation – for example, in the United States under ERISA, which is administered by the Department of Labor.

•Defined-contribution programs: Pension fund contributions are made by the employer, the employee, or both into a fund that will ultimately form the basis for pension benefits under defined-contribution pension plans. The employee’s share in the fund tends to vest after a number of years of employment, and may be managed by the employer or placed with various asset managers under portfolio constraints intended to serve the best interests of the beneficiaries. The employee’s responsibility for asset allocation can vary from none at all to virtually full discretion. Employees may, for example, be allowed to select from among a range of approved investment vehicles, notably mutual funds, based on individual risk–return preferences.

Most countries have several types of pension arrangements operating simultaneously – for example a base-level PAYG system supplemented by state-sponsored or privately-sponsored defined-benefit plans and defined-contribution plans sponsored by employers, mandated by the state or undertaken voluntarily by individuals.

The collision of the aforementioned demographics and heavy reliance on the part of many countries on PAYG approaches is at the heart of the pension problem, and forms the basis for the future growth of asset management. The conventional wisdom is that the pension problems that are today centred in Europe and Japan will eventually spread to the rest of the world. They will have to be resolved, and there are only a limited number of options in dealing with the issue:

•Raise mandatory social charges on employees and employers to cover increasing pension obligations under PAYG systems. This is problematic especially in countries that already have high fiscal burdens and increasing pressure for avoidance and evasion. A similar problem confronts major increases in general taxation levels or government borrowing to top up eroding trust funds or finance PAYG benefits on a continuing basis.

•Undertake major reductions in retirement benefits, cutting dramatically into benefit levels. The sensitivity of fiscal reforms to social welfare is illustrated by the fact that just limiting the growth in pension expenditures to the projected rate of economic growth from 2015 onward would reduce income-replacement rates from 45% to 30% over a period of 15 years, leaving those among the elderly without adequate personal resources in relative poverty.

•Apply significant increases in the retirement age at which individuals are eligible for full PAYG-financed pensions, perhaps to age 70 for those not incapacitated by ill health. This is not a palatable solution in many countries that have been subject to pressure for reduced retirement age, compounded by chronically high unemployment especially in Europe, which has been widely used as a justification for earlier retirements.

•Undertake significant pension reforms to progressively move away from PAYG systems toward defined-contribution and defined-benefit schemes such as those widely used in the US, Chile, Singapore, Malaysia, the UK, the Netherlands and Denmark. These differ in detail, but all involve the creation of large asset pools that are reasonably actuarially sound.

Given the relatively bleak outlook for the first several of these alternatives, it seems inevitable that increasing reliance will continue to be placed on the last of these options. The fact is that future generations can no longer count on the present value of benefits exceeding the present value of contributions and social charges as the demographics inevitably turn against them in the presence of clear fisca...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I Global Asset Management – Introduction and Overview

- Part II The Crisis of 2007–2008 and its Aftermath

- Part III Key Risk Factors in Asset Management

- Part IV Regulations and Governance

- Part V Operational Processes and Costs

- Part VI Operational Platforms and IT Strategies

- Part VII Future Challenges and Growth

- Index