eBook - ePub

More Scottish than British

The 2011 Scottish Parliament Election

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

More Scottish than British

The 2011 Scottish Parliament Election

About this book

Using official statistics, this book explores how the SNP managed to confound expectations and win a parliamentary majority in the 2011 Scottish General Election. Perhaps surprisingly, it was not constitutional politics or the return of the Conservatives to power in Westminster but domestic issues that decided the vote in the SNP's favour.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access More Scottish than British by Christopher Carman,Robert Johns,J. Mitchell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The 2011 Scottish Election in Context

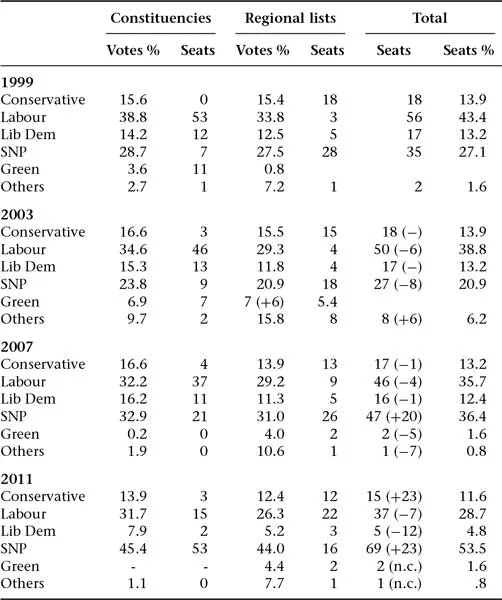

The elections to the Scottish Parliament in 2011 were unusual in a number of respects. The Scottish National Party (SNP) was defending a record in government for the first time in its history. It had governed Scotland since 2007 without an overall majority when it won 47 of Holyrood’s 129 seats, only winning one more seat than the Labour Party, which until then had governed Scotland in coalition with the Liberal Democrats since the establishment of the Scottish Parliament in 1999. The elections would be a test of both the SNP and minority government. The 2011 elections to Holyrood came a year after elections to the House of Commons, when Labour had been defeated after being in power since 1997. In the three previous Holyrood elections, there had been two years between Westminster and Holyrood elections taking place, which increased the prospect of a spill-over effect from the Westminster elections this time. The formation of a Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition in London altered the political landscape. Devolution came into being largely in response to the lack of support in Scotland for Conservative governments in the 1980s and 1990s (Denver et al. 2000). The 2011 elections were also the first devolved elections fought against the backdrop of serious economic and fiscal problems. Public expenditure had grown year on year under devolution, in common with spending across the UK, but this had now ended.

These novel aspects of the 2011 Scottish elections created a fascinating context in which to explore political behaviour but also challenges, not least given the need to disentangle the impact of different factors that might each have affected the outcome of the election. Disentangling the variables needs to be combined with understanding the impact each had on other factors. To what extent were expectations of what the Scottish government could deliver altered as a result of the economic crisis? To what extent did the election of a Conservative-led coalition increase the likelihood that the Scottish public would hold the UK government responsible for (prospective) public spending cuts? To what extent did the public take account of the absence of an overall majority in accrediting either blame or credit to the devolved government? This also raises the importance of the previous Scottish elections in 2007 when the SNP emerged with its slight lead over Labour. What expectations did voters have of an SNP government then as compared with 2011? And, of course, the SNP is committed to independence. To what extent and in what ways did the SNP’s constitutional position influence voters’ behaviour?

These questions were all-important in the Scottish elections but have resonance with questions asked in other liberal democracies, especially with tiered levels of elected government undergoing significant economic and fiscal dislocation. Governments across the world have been adversely affected by economic forces beyond their control but are nonetheless accountable to their electorates. Additionally, a growing literature addresses the impact on political behaviour of multi-tiered systems of representation. Understanding the 2011 Scottish election helps us understand political behaviour beyond Scotland. Equally, this study contributes to the literature on political behaviour in multi-tiered polities especially in the context of fiscal and economic crises.

From coalition to minority government

Vowles has identified two key theories in discussing public perceptions of coalitions, single-party and minority governments: clarity of responsibility and the role of ‘veto players’ (Vowles 2010: 372). Clarity of responsibility concerns which party or parties are accountable for policy decisions and thereby accountable to the electorate. It is generally assumed that coalition and minority government blur accountability as no single party can be held fully accountable for public policy. Minority government has been described as the least accountable form of government (Powell 2000). Such governments can blame opposition parties for failing to cooperate in pursuit of policy goals. The second theory considers accountability differently. The expectation of ‘minimum winning coalitions’ (Downs 1962: 47) suggests that coalitions do not require any more parties than would provide the government with a majority. The underlying assumption about minority government is that such governments confront a single majority veto player in opposition. In practice, minority governments may confront a divided opposition. The stability of a minority government will depend on the cohesion of the majority opposition. This is affected by the party system, which is affected in turn by the electoral system.

The Mixed Member Proportional (MMP) electoral system used for Holyrood elections, generally referred to in the UK as the Additional Member System (AMS), has its origins in debates within the Constitutional Convention, a cross/non-party body that formulated the outlines of a scheme of devolution between 1989 and 1992. The system involves voters electing a single district Member of the Scottish Parliament (MSP) in 73 constituencies plus an additional 56 members, seven from each of eight regions. Constituency MSPs are elected using single member districts with a simple plurality, first past the post system. The regional members are elected using closed party lists where members are selected using a system (modified D’Hondt) that takes account of the number of constituency MSPs elected within each region and each party’s share of the regional vote, thus providing the Parliament with a degree of proportionality.

The widely held assumption was that AMS would prevent any party having an overall majority. This assumption was based on past performance of the parties, or more specifically the Labour Party, under the simple plurality system in election to the House of Commons. In the first elections to the Scottish Parliament in 1999, Labour achieved an overall majority of constituency MSPs with 53 seats but only 3 list seats, falling 9 seats short of an overall majority. Labour formed a coalition with the Liberal Democrats, providing an overall majority of 8 with 73 seats. The same coalition was formed following the 2003 elections after Labour lost 6 seats, but remained the largest party, and the Liberal Democrats won 17 seats, gaining a constituency seat but consequently losing a list seat. Partnership Agreements between the coalition parties set out the programme for government after 1999 and 2003. But in 2007, when the SNP emerged with its slight lead over Labour, and well short of an overall majority, the Liberal Democrats chose to move out of government. Alex Salmond, as leader of the SNP in Holyrood, defeated Jack McConnell, Labour’s leader in the election of Scotland’s First Minister by 49 votes to 46 with 33 abstentions. The two Green MSPs voted for Salmond along with the contingent of SNP MSPs. An agreement, short of a coalition, had been reached with the Greens, on three ‘core issues’: opposition to building new nuclear power stations; agreement to early legislation to reduce climate change pollution annually; and agreement that independence would make Scotland more successful and that the parties would work to ‘extend the powers of the Scottish Parliament’ (SNP and Greens 2007). These were matters on which the two parties agreed and required no compromises. The Greens agreed to support the minority government ‘in votes for First Minister and Ministerial appointments’ and the SNP agreed to consult the Green MSPs in advance of each year’s legislative and policy programme as well as key measures announced in-year, the substance of the budget and to nominate a Green MSP as convener of a subject committee in the Parliament (SNP and Greens 2007).

In his speech prior to the vote, Alex Salmond had said,

This Parliament is a proportional Parliament. It is a Parliament of minorities where no one party rules without compromise or concession. The SNP believes that we have the moral authority to govern, but we have no arbitrary authority over this Parliament. The Parliament will be one in which the Scottish Government relies on the merits of its legislation, not the might of a parliamentary majority. The Parliament will be about compromise and concession, intelligent debate and mature discussion. That is no accident. If we look back, we see that it is precisely the Parliament that the consultative steering group – the founding fathers of this place – envisaged.

Official Report Scottish Parliament

(16 May 2007, col. 24)

The new First Minister discovered the virtues of a proportional Parliament. The much-trumpeted ‘new politics’, implying a more consensual approach, which some advocates of devolution had hoped would emerge with devolution, was finally becoming a reality. New politics operated alongside typically British adversarial politics within the Holyrood chamber due to the necessity of parliamentary arithmetic rather than a revolution in political attitudes. Westminster-style adversarial politics lived on alongside the need continuously to construct coalitions over the next four years in Holyrood.

During election campaigns, parties do not tend to indicate with whom they will coalesce in the event that no party has a majority (Katz 1997: 165–167). Parties in a coalition will each claim primary credit for a popular policy or try to evade responsibility for less popular policies (Gallagher, Laver and Mair 2005), as both Scottish coalition parties did in 2003 on policies such as opposing tuition fees for university students and offering generous ‘care for the elderly’ policies. It is difficult for a minority government to keep its promises and easier to evade responsibility as it does not have a majority. This might allow it to ditch promises that might have made sense for electoral purposes but proved costly in implementation. Popular SNP manifesto commitments in 2007 included abolishing the council tax and replacing it with a local income tax. Absence of a parliamentary majority prevented this policy chance but, argued the SNP’s critics, also meant that the SNP could avoid the troublesome business of introducing a new form of local taxation (Table 1.1).

It has been suggested by a leading scholar of minority government that conventional wisdom associating minority cabinets with ‘instability, fractionalization, polarization, and long and difficult formation processes’ is a ‘historically bounded proposition’ (Strøm 1990: 89–90). The UK has experienced minority government at various intervals during the twentieth century: 1910–1915; 1924; 1929–1931; 1974; 1976–1979; 1997. These have usually coincided with periods of economic instability though this coincidence had little to do, at least directly, with minority government. However, this ‘historically bounded’ association may have coloured expectations of minority government. Strøm’s exhaustive analysis of minority government (Strøm 1990) challenges these negative associations, and reminds us of how common minority government is in some parliamentary democracies and that minority can be a rational response by party leaders. David Butler, too, has noted that minority governments outside the UK have proved ‘quite stable with few of the dire consequences usually suggested’ (Butler 2008: 11). As Strøm notes, minority status allows a government maximum flexibility in seeking support for its policies with shifting coalition strategies, though it also makes them vulnerable to defeat (Strøm 1990: 97). Green-Pedersen also noted, ‘shifting coalition strategies offer minority governments optimal conditions for having their policies passed, but it also renders them vulnerable to defeat’ (Green-Pederson 2001: 56). Research on how successive Danish minority governments have operated is particularly relevant. Scottish government officials prepared for the possibility of minority government before 2007 by enquiring into the Danish experience.

Table 1.1 Results of Scottish Parliament elections, 1999, 2003, 2007 and 2011

Note: Rounding may result in columns adding to more than 100 per cent.

When a minority government has only one way of building a majority, this gives the supporting opposition party veto powers over individual policies as well as over maintaining the governing party in office. The SNP found itself with limited options in building majorities (see Table 1.2). Minority governments require more than one way of building a majority to maximize its prospects of ensuring its policies pass through parliament. The SNP’s advance in 2007 occurred partly due to the decline of the ‘Others’ but meant that there were fewer means of combining to create a majority in Holyrood. Nonetheless, assuming coherence of party groups in Holyrood, the SNP had five ways of constructing a parliamentary majority after 2007 prior to the appointment of a Conservative MSP as Presiding Officer. Margo MacDonald, the former SNP MSP, sitting as the only Independent since 2003, might prove important in Holyrood votes. The period 2007–2011 would test an inexperienced party governing without a majority. The keys to success for minority governments lie in winning important votes, especially on budgets, but also in an ability to devise policies for which it can claim credit without a parliamentary majority and use existing powers to pursue its policy programme.

Three important caveats have to be noted with respect to majority building. First, much policy-making occurs within the framework of existing legislation and the powers granted to ministers do not require a parliamentary majority. Alex Salmond was keen to quote Donald Dewar, his Labour predecessor as First Minister, who had said: ‘As part of the perfectly normal constitutional arrangement, except in certain circumstances, the Scottish Executive is not necessarily bound by resolutions or motions passed by the Scottish Parliament’ (Scottish Parliament 31 May 2007). Secondly, theatrical, adversarial politics often hides a willingness to cooperate. This became apparent in annual budget debates during which the minority SNP government had sought to build a parliamentary majority voting in favour of each budget. Labour, the main opposition party, calculated how to oppose each SNP budget formally while, at the same time, ensuring that the SNP government was not brought down by the defeat of the budget. This was highlighted in 2009. Against the expectations of all other MSPs, the two Green MSPs decided to join with Labour and Liberal Democrat MSPs to vote against the SNP budget, causing the budget to fall. This would normally precipitate an election but a second budget, almost identical to the first, was proposed, and won the support of Labour and Liberal Democrat MSPs who had opposed the original measure (on the assumption that the Green MSPs would vote for the budget) and thereby allowed the amended budget to pass. Thirdly, and most important in the context of voting behaviour, there is the question of the extent to which the electorate are aware of the existence of, and constraints upon, a minority government. As is well documented in the politics literature, minority governments must build a unique coalition of the willing on each legislative measure put forward. This need to constantly build a voting majority through negotiation and compromise is not something that we would expect the voting public to understand and even consider when evaluating the minority government.

Table 1.2 Majority building 1999–2003; 2003–2007; 2007–2011

Majority combinations 1999–2003 Parliament

Labour 56 MSPs requires 9 other for minimum winning coalition

| i. | With SNP = 56 + 35 |

| ii. | With LibDems = 56 + 17 |

| iii. | With Conservatives = 56 + 18 |

SNP 35 MSPs requires 30 others for minimum winning coalition

| i. | With Conservative and Liberal Democrats = 35 + 18 + 17 |

Majority combinations 2003–2007 Parliament

Labour 50 MSPs requires 15 for minimum winning coalition

| i. | With SNP = 50 + 27 |

| ii. | With LibDems = 50 + 17 |

| iii. | With Conservatives = 50 + 18 |

| iv. | With Greens, SSP, and three ‘Others’* = 50 + 7 + 6 + 3 |

*This grouping consisted of 4 ‘Others’ in total.

SNP 27 MSPs requires 38 others for minimum winning coalition

| i. | With Conservatives+ LibDems+ Greens = 18 + 17 + 7 |

| ii. | With Conservatives+ LibDems+ SSP = 18 + 17 + 6 |

| iii. | With Conservatives+ LibDems + 3 ‘Others’* = 18 + 17 + 3 |

*This grouping consisted of 4 ‘Others’ in total.

Majority combinations 2007–2011 Parliament

SNP 47 MSPs requires 18 others for minimum winning coalition.

| i. | With Labour 47 + 46 |

| ii. | With Conservatives + Liberal Democrats = 47 + 17 + 16 |

| iii. | With Conservatives + greens = 47 + 17 + 2 |

| iv. | With Conservatives + one other*+ 47 + 17 + 1 |

| v. | With Liberal Democrats + greens = 47 + 16 + 2 |

Labour 46 MSPs requires 19 others for minimum winning coalition.

| i. | With Conservatives + Liberal Democrats = 46 + 17 + 16 |

| ii. | With Conservatives + Greens = 46 + 17 + 2 |

| iii. | With Liberal Democrats + Greens+ Independent = 46 + 16 + 2 + 1 |

Multi-level elections

The establishment of the Scottish Parliament created a new tier of elected representatives. Public perceptions of the devolved government, especially as it relates to attitudes to the Westminster Parliament and government, can be expected to have influenced political behaviour. A well-established literature on US elections suggests that mid-term ele...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- 1. The 2011 Scottish Election in Context

- 2. Results and the Sources of Party Support

- 3. Parties and Leaders

- 4. Performance Politics at Holyrood

- 5. How ‘Scottish’ Was this Election?

- 6. Party Choice in 2011

- Appendix 1: The 2011 Scottish Election Study

- Appendix 2: Full Results of Statistical (Regression) Analyses

- Notes

- References

- Index