In 2010, I was invited to guest-edit a special issue of the journal Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory. My only instructions were to pick a “sexy” topic that would appeal to a broad readership. I don’t exactly recall how I came up with the idea of “Evil Children in Film and Literature,” but it was at least partly due to the fact that I grew up reading horror, especially the works of Stephen King, for whom the genre seems inextricably tied to youth. Certain that the subject had already been done to death, I did some preliminary research and found that there was actually very little written on the topic. Meanwhile, around me, evil children were popping up everywhere, not only in literature and film, but also on television, in video games, and even in music videos. Since the publication of the two-part special issue of Lit in 2011, subsequently published by Routledge in 2013 as The ‘Evil Child’ in Literature, Film and Popular Culture, evil children have spawned across all realms of popular culture. In 2011, I had identified 200 films that portrayed some kind of arguably evil child, over 100 of which had been produced since the year 2000; by my last count, that number is closer to 600, with almost 400 made in the new millennium.

And that’s only film. Television has also capitalized on the subject. News broadcasts repeatedly latch onto stories about child criminals, a subject of significant enough interest to earn its own documentary series Killer Kids (2012–) on the Lifetime Network. Evil children have also made a foray into fictional television programming, appearing frequently as felons on Law and Order: Special Victims Unit (1999–) or Criminal Minds (2005–) or as supernatural adversaries in paranormal-themed shows such as The X-Files (1993–2002) or Supernatural (2005–). Reality television offers viewers an intimate look at misbehaving youth on Nanny 911 (2004–), Supernanny (2005), Toddlers & Tiaras (2009–), and Beyond Scared Straight (2011–). Neither can one ignore related developments in animated television sitcoms, such as the mischievous Bart on The Simpsons (1989–), the downright nasty Eric Cartman on South Park (1997–), or the maniacal Stewie Griffin in Family Guy (1999–).

Evil children are a prominent element of video games as well, appearing in multiple installments of the Silent Hill, Bioshock, and F.E.A.R. series. Rule of Rose (2006) contains some shocking instances of child violence and cruelty, and the 2010 game Lucius actually allows you to play as a child antichrist. American McGee’s Alice (2000) and its sequel Alice: Madness Returns (2011) turn Wonderland into a dangerous landscape and arm your player character—Lewis Carroll’s iconic protagonist—with a butcher knife. Nor is Alice the only character from children’s literature to have undergone a menacing makeover: both Red Riding Hood and Peter Pan, for example, have been transformed into ominous figures in a variety of texts, only some of which are intended for adults.

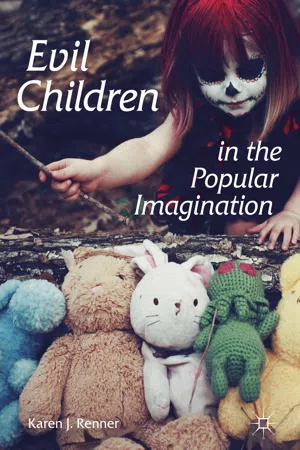

Evil children have become familiar faces in young adult (YA) literature, too; one need only think of Tom Riddle in the Harry Potter series and the children who fight to the death in Suzanne Collins’s popular trilogy, The Hunger Games. The appearance of evil children in video games and YA literature is especially striking since both often target audiences who could be the age-mates of these terrifying youth. That evil children appear as both avatars and adversaries suggests that the figure has become a potential source of empowerment for kids as well as a figure against which they can define their own identities. Nowhere is this more evident than in the work of Brit Bentine, the photographic genius behind Locked Illusions Photography, of which the cover to this book is an example. The children she photographs choose to dress up like bloodthirsty zombie ballerinas and murderous mermaids or take on the identity of some terrifying monsters, such as the creepy nurses in Silent Hill, Pinhead from Hellraiser, or Billy the puppet from Saw.

But perhaps the strongest evidence that evil children are now a permanent fixture in the popular imagination is that they’ve become a fitting subject for satire. Both Hell Baby (2013) and Cooties (2014) spoof the genre. Furthermore, in 2013, College Humor posted a short video on their YouTube channel entitled “Horror Movie Daycare,” which has since earned almost 4.5 million views. In less than three minutes, the clip makes references to The Shining, Village of the Damned, Children of the Corn, Let Me In, The Omen, The Ring, and The Exorcist, and the viewer needs to get these references in order for the video to be funny. The video thus presumes that a general knowledge of iconic evil children has become commonplace.

As expansive as the genre may be today, stories about evil children have a relatively short history. Although one can find earlier examples—“Cruel Frederick” in Henrich Hoffman’s Der Struwwelpeter (1845), for example, or Miles and Flora in Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (1898)—it wasn’t until the 1950s that evil children first appeared with any serious regularity in popular culture. During this decade, a variety of influences came together to create a new focus on and fear of youth. To explain, George Ochoa focuses on the simple fact of demographics: “The horror-film ethical rule about being wary of young people only came into existence when there were a great deal of young people around: during and after the baby boom of about 1946–1964, a period that saw a great rise in the birth rate” (2011, 67). The 1950s also saw juvenile crime double, and both the mass media and popular culture picked up on the theme, heightening anxieties about teenagers (Young and Young 2004, 32). This was also the era in which teen culture first rose to prominence, dethroning the adult world that had held center stage (Owram 1996, 144–146) and likely earning its enmity in the process. In addition, new forms of mass entertainment, such as radio, television, rock music, and comic books, raised fears about dangerous influences that could corrupt young minds.

Many of the evil child texts that first appeared were short stories, such as Ray Bradbury’s “The Small Assassin” (1946) and “The World the Children Made” (1950), later known as “The Veldt”; Richard Matheson’s “Born of Man and Woman” (1950); and Jerome Bixby’s “It’s a Good Life” (1953), later adapted for an episode of The Twilight Zone in 1961. Some novel-length treatments popped up as well, including Agatha Christie’s Crooked House (1949), William Golding’s The Lord of the Flies (1954), William March’s The Bad Seed (1954), and John Wyndham’s The Midwich Cuckoos (1957); all but the first were promptly adapted into films.

During the 1960s, several well-known authors, among them Shirley Jackson, Flannery O’Connor, and Joyce Carol Oates, also focused their Gothic lenses upon the subject of children in We Have Always Lived in the Castle (1962), “The Lame Shall Enter First” (1965), and Expensive People (1968), respectively. But it was Ira Levin’s Rosemary’s Baby (1967) and Roman Polanski’s adaptation of the novel the following year that proved the most popular entries into the evil children genre. Influenced by and perhaps hoping to capitalize upon the success of Rosemary’s Baby, authors in the 1970s produced an enormous number of novels about evil kids. Many became instantly seared into cultural memory, aided by the cinematic renditions that directors were quick to supply, the most successful ventures being William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel The Exorcist, adapted for the screen in 1973, and Thomas Tryon’s bestselling novel The Other (1971), which also received a cinematic tribute in 1972. Other narratives, like It’s Alive (1974) and The Omen (1976), began as movies and were then novelized.

During the 1970s, several writers who would later become virtuosos of horror launched their careers with stories centering on evil children. Dean Koontz published Demon Child in 1971 under the pseudonym Deanna Dwyer, but his first big success came with Demon Seed (1973); the book was made into a 1977 film starring Julie Christie. The first and most popular of Anne Rice’s Vampire Chronicles, Interview with the Vampire, first saw print in 1976; a considerable portion of that novel is devoted to a child vampire, Claudia. Stephen King, too, first received serious attention after publishing his novel Carrie (1974), and Brian De Palma’s 1976 cinematic adaptation only bolstered his reputation. King promptly went on to write several other stories about evil and evilish children, including “Children of the Corn” (1977), The Shining (1977), Firestarter (1980), and Pet Sematary (1983), all of which were eventually made into movies.

These horror novels transformed the evil child narrative from a fringe curiosity to a mainstream interest, allowing lesser-known writers, including John Saul, Andrew Neiderman, and Ruby Jean Jensen, to build a career on the genre. Zebra horror, a paperback division of Kensington Publishers, relied greatly on the evil child genre during its heyday, which lasted from roughly the mid-1980s to late 1990s. Rather than count on the pull of a well-known author to draw in readers, Zebra paperbacks employed similar packaging, suggesting that each book, regardless of author, would provide a comparable product—and one of the products Zebra often peddled was the evil child narrative. Zebra offerings in this subgenre are remarkably similar: covers include a frightening image of a youngster, a title that somehow relates to children (e.g., Child’s Play, Only Child, Daddy’s Little Girl, and Teacher’s Pet) in raised foil letters with the author’s name in much smaller font below, and taglines and rear-cover descriptions that promise stories about evil children. Patricia Wallace’s Twice Blessed (1986), for example, features a skeleton with long red hair and a nurse’s cap holding twin babies: “Their innocent eyes were twin mirrors of evil!” the front cover declares while the back confirms that their mother will discover that “[h]er two sweet babies had become one—in their dark powers of destruction and death.” Zebra Horror’s marketing strategy affirms that by the 1980s the genre was established enough to attract its own fan following. Today’s pervasive obsession with evil children narratives is thus a crescendo that has been building since the 1950s and which so far shows no sign of quieting.

Academics have only recently given the subject sustained attention, however. When my special issue of Lit was published in 2011, it was—as far as I know—the only book solely devoted to the topic of evil children aside from Adrian Schober’s Possessed Child Narratives in Literature and Film (Palgrave Macmillan, 2004). Edited collections, such as Gary Westfahl and George Slusser’s Nursery Realms: Children in the Worlds of Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror (University of Georgia Press, 1999) and Steven Bruhm and Natasha Hurley’s Curiouser: On the Queerness of Children (University of Minnesota Press, 2004), contained essays on the evil child. In addition, several noteworthy single-author studies included chapters on evil children in popular culture: Kathy Merlock Jackson’s Images of Children in American Film (1986), Sabine Büssing’s Aliens in the Home (1987), Ellen Pifer’s Demon or Doll: Images of the Child in Contemporary Writing and Culture (2000), and Karen Lury’s The Child in Film: Tears, Fears, and Fairy Tales (2010). Since then, a number of works have been published on the subject, including Dominic Lennard’s Bad Seeds and Holy Terrors: The Child Villains of Horror Films (2014), Andrew Scahill’s The Revolting Child in Horror Cinema: Youth Rebellion and Queer Spectatorship (2015), and T. S. Kord’s Little Horrors: How Cinema’s Evil Children Play on Our Guilt (2016), Lost and Othered Children in Contemporary Cinema, edited by Debbie Olsen and Andrew Scahill (Lexington, 2012), Markus Bohlmann and Sean Moreland’s edited collection Monstrous Children and Childish Monsters: Essays on Cinema’s Holy Terrors (2015), and another edited by Simon Bacon and Leo Ruickbie entitled Little Horrors: Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Anomalous Children and the Construction of Monstrosity (2016). And this list doesn’t take into account all the amazing articles that have been written on the subject. An inaugural global conference on “Evil Children” is even scheduled to be held in Portugal in April 2017. The topic of evil children has definitely hit its scholarly stride.

I suppose it’s about time I explain what I mean by the term “evil children.” I’ll start with the first word. Early on in this project, I decided that I wasn’t comfortable calling anyone who existed in this world “evil.” I felt confident that I could label an act “evil,” but attaching that label to the person who had committed that act seemed problematic, as it would suggest that the person not only had intentionally and willfully committed an act that they knew to be evil without fair cause but also that they were, as a result, incapable of being anything other than evil from thereon out. The word “evil” required such a sweeping and permanent judgment that it seemed to me that “evil” could only exist in a supernatural or at least supernormal world. I therefore chose to focus on supernatural narratives, storylines that might allow for the possibility of “evil” as a metaphysical principle.

Now I was left with the equally problematic term, “children.” Children are, after all, consummate shapeshifters who change form depending on whether we are focusing on physical, psychological, or socio-legal markers. Actually, this is inaccurate; we are the ones who force the child to fit into whatever mold we choose to provide; as James Kincaid claims, “[w]hat a ‘child’ is…changes to fit different situations and different needs” (1992, 5). Even if we pick a very specific criteria—the age of criminal responsibility, say—the boundary between adult and child depends on who’s doing the defining. Nations certainly don’t agree, and in the US, states even have different opinions about the matter, and individual legal cases don’t necessarily abide by those rules anyway. And the laws have dramatically changed throughout time. For example, in the UK in 1708, 7-year-old Michael Hammond and his 11-year-old sister were executed for stealing bread; precisely 200 years later, the Children Act banned the execution of juveniles under the age of 16. For the purposes of this book, I have decided to distinguish child from adult using the commonly cited age of majority, 18; those younger will be considered “children.”While you might think that such a broad definition of “children” would result in a diverse group, evil child narratives ultimately focus on a pretty narrow bunch. The majority of evil child characters are, by far, white, middle- to upper-class boys; a distant second would be white, middle- to upper-class girls, who in particular dominate the categories of the possessed child and changeling. It might seem surprising that minority youth are not the focus of evil child narratives, given that they are so frequently the subject of racist fears. However, I think that excluding minorities from the evil child genre reflects racist thinking. To me, the underlying assumption is that “those” children have a natural propensity for evil, and so casting them in the role of evil child would be redundant, or at least anticlimactic. It is the supposed contrast between whiteness and evil that creates tension—that is “what happens when the face of evil carries with it an uncanny reminder of the face of innocence,” to quote Chuck Jackson’s “Little, Violent, White: The Bad Seed and the Matter of Children” (2000, 66).

While defining each term separately proved difficult, bringing the words together seemed to create an oxymoron. In my mind, “evil” implies intention and choice, and a child, by definition, would seem to lack the maturity and forethought necessary for purposeful decision-making. At least, the denial of rights and legal responsibility to children under 18 is based on such an assumption. What I ultimately came up against was the contradiction that stumps the legal system time and time again, at least in countries like the USA and UK: when awarding rights to children, we err on the side of caution, believing them not responsible enough to vote, drink, or serve in the military. However, when children commit crimes, we often want to hold them responsible, believing that they must understand the differences between right and wrong and can act accordingly. Children are thus constantly held to a double standard that views them as too young to be trusted but old enough to know better. In turn, our rules and laws depend on a fantasy concept of The Child, who is so unwise and vulnerable as to need our protection and guidance but so naturally innocent and good as to be incapable of serious wrongdoing. The Child can never exist in reality, and neither can The Evil Child. To be truly evil, a child would have to be capable of mature intention and responsible decision-making, but would such a child still be a child? And, if so, what would be our justification for denying him or her any rights, then?

This book therefore has a twist ending, and—spoiler alert—here it is: evil children don’t really exist in the popular imagination. As strange as it sounds, the history of evil child narratives has largely been a series of efforts to confirm the essential innocence of children. The task is accomplished by the supernatural elements of the plot—Satanic genes in The Omen, a possessing demon in The Exorcist—that exculpate the child from responsibility for even the most heinous of deeds. These supernatural forces symbolize those causes of deviant juvenile behavior so often pointed to in the real world as causing an individual child to stray from the ideal of The Child, such as defective genetics, flawed parenting, faulty educational practices, bad influences like violent video games and a sex-obsessed consumer society, or a war-mongering culture. In evil child narratives, evil is therefore an effect, not a cause, a response to an influence rather than an essence. Evil child texts are essentially unwilling to give children credit for the evil they commit; better instead to envision them as corrupted. At the same time, while the texts imply that evil children know not what they do, the texts ask us to be horrified by their actions anyway and sometimes even accepting of their executions...