- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

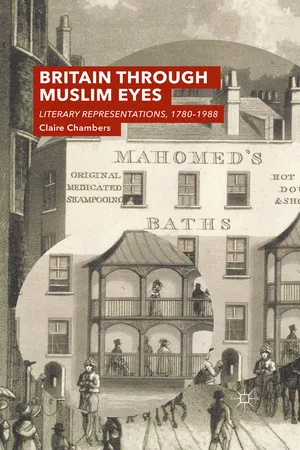

What did Britain look like to the Muslims who visited and lived in the country in increasing numbers from the late eighteenth century onwards? This book is a literary history of representations of Muslims in Britain from the late eighteenth century to the eve of Salman Rushdie's publication of The Satanic Verses (1988).

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Britain Through Muslim Eyes by Claire Chambers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Asian Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Travelling Autobiography

1

Orientalism in Reverse: Early Muslim Travel Accounts of Britain

Introduction

Muslims now number almost 2.7 million in Britain or approximately five per cent of the population (Office for National Statistics, 2011). The rise to the current figure became markedly steep after the late 1940s, mostly due to the aftermath of empire and a post-war demand for manual labour. However, it is important to recognize that Muslims have visited, lived, and worked in Britain for hundreds of years. As Sukhdev Sandhu observes:

Blacks and Asians tend to be used in contemporary discourse as metaphors for newness. Op-ed columnists and state-of-the-nation chroniclers invoke them to show how, along with deindustrialization, devolution and globalization, Englishness has changed since the end of the war. That they had already been serving in the armed forces, stirring up controversy in Parliament, or […] helping to change the way that national identity is conceptualized, often goes unacknowledged. (Sandhu, 2003: xviii)

Members of the New Right, politicians from a broad range of the political spectrum, and many mainstream newspapers consistently erase the contributions of Muslims, Asians, blacks, and other ‘others’ from British history, portraying migrants in Britain as constituting an unwelcome post-war invasion. They nostalgically recall a mythical ‘Englishness’ which was apparently lost with the arrival of these strangers.

In this chapter I delineate the early migration history and travel writing of Britain’s largest religious minority, the Muslim community. The first exchanges between Europe and the ‘Islamic world’ in fact took place in the medieval period, which was also the era of the Crusades and cultural and scientific dialogue between Europeans and Arab Muslims. Nabil Matar’s Islam in Britain, 1558–1685 educates readers that an especially significant presence of Islam in Britain is traceable back to the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This manifests itself in the conversion of some British Christians to Islam, in a fascination with this issue of ‘turning Turk’, in translations of Islamic texts including the Qur’an, in commerce, and later in coffee house practices (Matar, 1998). Humayun Ansari’s research shows that some Muslim scholars, diplomats, freed slaves, and merchants found their way to Britain as early as the twelfth century (2004: 26–7). Few of these early travellers left behind travel narratives about their stays in Europe. Those that did, such as the cosmopolitan seventeenth-century Turk Evliya Çelebi (c.1611–82), wrote extensively about their peregrinations, but did not venture further north than Ottoman Europe (Dankoff and Kim, 2010).

In a later study, Europe Through Arab Eyes, 1578–1727, Matar translates sixteenth- to eighteenth-century Arabic manuscripts. If they portray English people at all, these texts tend to frame them as an ‘enemy’ or inadvertent ally in the fight against Spain (2009: 145). We are shown Englishmen fighting a sea-battle against the ‘Spanish tyrant’ (2009: 147). They also captured the (probably Christian) Moroccan Ambassador, Bentura de Zari, who spent months under house arrest in London between 1710 and 1713 (2009: 232–5). This early view of Britain is hostile or at least wary and presented at one remove. It is very different from that of the travel writers of the late eighteenth century onwards. As the chapter will demonstrate, the later travel writer adopts the perspective of a resident (albeit, usually, a temporary one). This resident interacts with British people as neighbours, employers, patrons, friends, and adversaries, rather than at a distance as in the Renaissance manuscripts.

Researchers are beginning to correct earlier assumptions about the European origins of the Renaissance, the intellectual movement which technically starts in the fourteenth century but whose scholastic tentacles reach back to the twelfth. The Age of Discovery was in fact based on very strong traffic with the so-called Muslim world. I am thinking, in particular, of Britons like Adelard of Bath (c.1080–c.1152). Adelard went to Turkey ‘determined to learn from the Muslims rather than kill them under the sign of the cross’ (Lyons, 2009: 2) and brought back Arab scientific knowledge that was to transform British and European society. With a contrasting conversion agenda, Peter the Venerable, Abbot of Cluny (C. 1092–1156), travelled to Muslim Spain in 1142. Hoping that it would help him understand his potential converts, Peter coordinated a group of scholars who produced the first translation of the Qur’an (Elmarsafy, 2009: 1). The fact that these two adventurers come out of similar temporal and geographical contexts, in a Britain heading for the scientific and cultural flourishing of its Renaissance, suggests the importance of Muslim knowledge in facilitating this intellectual efflorescence.

Interchange between the Muslim world and Europe accelerates during the Age of Reason. The Enlightenment was a fluid combination of events, people, institutions, and forms of knowledge, with more contradiction and diversity than unity. The broader trends that the discourse of this time exhibit, however, are the privileging of reason and experience, the rejection of religious authority in favour of a more materialist, liberal philosophy, and general optimism about the possibility of progress through education. In The Enlightenment Qur’an, Ziad Elmarsafy describes the vigorous exchanges that took place between the Muslim world and Enlightenment Europe in the long eighteenth century. He writes of a ‘secret attraction across the boundary between cultures and religions’. This colonial desire manifested itself through the Qur’an being ‘considered simultaneously desired and dangerous’ by European Christian thinkers in this period (Elmarsafy, 2009: 1, 8; see also Young, 1995). Our gaze in these pages is directed the other way, towards Muslims travelling in the West, specifically Britain. I examine these travellers’ fears for their spiritual safety in, and concurrent attraction to, the United Kingdom. It is nonetheless worth remembering Elmarsafy’s cogent point about the two-directional nature of this covert desire.

Most of the discussion of the post-Second World War period comes later in this book, but it is worth foreshadowing that black and Asian anti-racist protesters from the 1960s onwards countered the common bigoted taunt of ‘Go back to where you came from’ with the phrase, ‘We’re here because you were there’ (Webster, 2011: 122). This indicates that it is not so easy to separate ‘here’ and ‘there’, past and present, in this island nation with its long history of exploration, colonization, and exploitation. Many of the early migrants who came to Britain were highly skilled and made an inestimable contribution to the nation’s quality of life (Visram, 1986: 192–3). Other pre-war migrants came because they were needed to do jobs that British people were reluctant or unsuited to take, particularly in maritime and childcare roles. Rozina Visram memorably summarizes their positions in the title of her pioneering 1986 history of South Asian migration to Britain from the eighteenth century until Partition: ‘Ayahs [nannies], Lascars [seamen], and Princes’. To this, she adds some other categories: servants, travellers, students, and soldiers (Visram, 1986). More recently Ruvani Ranasinha has added still more: ‘doctors, traders, pedlars, maritime workers, [...] and the petitioner class’ (Ranasinha et al., 2012: 2, fn. 4). Given this book’s focus on Muslims, my contribution in Chapter 3 will be to add to these lists at least one more group, that of white British converts to Islam. Over the course of the next two chapters, I concentrate on the elite end of the migrant spectrum – princes, travellers, and students – because these are the people most likely to leave behind written records of their journeys. In the margins of one of the texts discussed in Chapter 2, the Aga Khan’s World Enough and Time, the reader catches a rare glimpse of a Muslim servant in Britain. He is probably the most high-profile of this class, Queen Victoria’s munshi, Abdul Karim.

In this chapter, I study four figures from the earliest period in which Muslim sojourners began portraying their stays in Britain. Written in the 1780s, Mirza Sheikh I’tesamuddin’s Shigarf-nama-‘i Vilayat or The Wonders of Vilayet is the account by an Indian of Persian heritage of his mixed feelings on coming to Britain in 1765. The next author, Bihar-born Sake Dean Mahomed, was unique amongst these early travellers for having stayed on in Britain. He married an Irish woman, put down roots, and produced his The Travels of Dean Mahomet (1794) in English for a Western audience. Another Indian from a Persian background, Mirza Abu Taleb Khan, wrote his Travels at the turn of the nineteenth century, and was the early Muslim writer who found the most to criticize in Britain and Ireland. Finally, Reeza Koolee Meerza, Najaf Koolee Meerza, and Taymoor Meerza were three princes from Iran who stayed in Britain for several months in 1836. The middle brother Najaf Koolee Merza wrote a journal about their experiences in the country.

One of this chapter’s most revealing discoveries is that there existed hazy borders between Indian, Iranian, and Arab Muslim travellers and authors. The frontier between Iran and India is especially amorphous and shifting because these two countries shared overlapping experience of the East India Company’s incursions, a physical border, and the Persian language. Without occluding the many differences between them, in this book as in my last (Chambers, 2011a), Arabs, Africans, Persians, British converts, and South Asians are discussed alongside each other. This is a productive approach, for the Muslims of these regions share religious backgrounds and practices, social networks, and some literary tropes. In Postcolonial Life-Writing, Bart Moore-Gilbert notes in passing that ‘travel […] foregrounds issues of embodiment, in relation to diet, physical comfort and health’ (2009: 89). The final feature which is held in common by the nine writers under scrutiny in Part I is this concern with maintaining (or flouting) Islam’s prescriptions for feeding, dressing, cleaning, and keeping healthy the Muslim body. Anxieties about eating halal food, wearing modest clothing, and performing appropriate ablutions and rituals come up again and again in the early travel and life writing surveyed here.

Mirza Sheikh I’tesamuddin

Probably the earliest book-length account by a Muslim about experiences in Britain is Shigarf-nama-‘i Vilayat.1 This manuscript was first produced some time between 1780 and 1784. It was translated and abridged from the Persian into English by James Edward Alexander in 1827, and into the Bengali title Vilayet Nama by Abu Muhammad Habibullah in 1981 (Alexander, 1827; Habibullah, 1981; Haq, 2001: 13). I work here with Kaiser Haq’s The Wonders of Vilayet: Being the Memoir, Originally in Persian, of a Visit to France and Britain in 1765 (I’tesamuddin, 2001), an adept amalgamation and modernization of the two earlier translations. In many ways, The Wonders of Vilayet is emblematic of the experiences and cultural production of these early Muslims visitors to Britain. Its author Mirza Sheikh I’tesamuddin (c.1730–1800) was a Sayyid; in other words, his family, which fled the Mongol invasion of Iran and came to India in the sixteenth century, claimed descent from the Prophet Mohammed. The family was highly cultured and its members tended to work in administration and law. I’tesamuddin was brought up in Panchnoor, West Bengal, and became a munshi, a respected scholar of Persian (at that time the official language), for the Mughal Emperor Shah Alam II and the East India Company (Haq, 2001: 9–10). In the mid-eighteenth century, as the East India Company under the command of Robert Clive was battling to establish its rule in India, there came an opportunity for I’tesamuddin to go West. Evoking Allah, as he does at intervals throughout the volume, he departed for England.2

The first stage of I’tesamuddin’s journey ends with his arrival in Mauritius, where he meets and feels a sense of kinship with a sareng, or officer, and ‘seven other Moslem lascars’ from East Bengal and elsewhere in India who are celebrating Eid (36). I’tesamuddin also makes stops in Pegu, Malacca, the Maldives, Madagascar, Cape Town, and France before arriving in England. En route, he describes encounters with factual and fictitious beings, including cannibals, Muslim converts, slaves, mermaids, and flying fish. Michael H. Fisher demonstrates that travel writers in this period borrowed from the techniques of fiction, and from other writers, in the construction of these ‘exotic adventures’ (1996: 222–7, 222). I’tesamuddin’s inclusion of such fantastical creatures as cannibals and mermaids therefore complies with generic conventions. Furthermore, Jagvinder Gill points out that The Wonders of Vilayet’s title ‘conforms to an Orientalist paradigm in that it emphasises the idea of awe and wonder, both crucial elements of the picturesque travelogue’ (2010: 85). After a six-month sea voyage, his ship finally docks in Dover, where I’tesamuddin and others are immediately detained because one of their fellow passengers has brought contraband fabrics into the country (53).

Despite this inauspicious start to his visit, I’tesamuddin is generous in his praise for what he often refers to as the ‘hat-wearing Firinghees’ of ‘Vilayet’ (22, 25, 29, 44, 46, 87, 118). In this phrase to denote foreigners from England,3 hats are used as a way of differentiating Firinghees or Franks from Turks, Persians, Arabs, and Indians, who at this time wore fezes, tarbushes, or turbans. He writes that Europeans have ‘attained astonishing mastery over the science of navigation’ and that British women are ‘lovely as houris’, or the maidens expected to wait on good male mortals in heaven (30, 53). He is less cordial about black people, or habshis, and the French. For example, he troublingly describes Malacca’s indigenous peoples as ‘hav[ing] satanic countenances and bestial natures’ (40), while he seems to have imbibed Britishers’ prejudices against their neighbours across the Channel, calling them ‘dirty eaters’, many of whom ‘cannot afford shoes’ (45, 50). I’tesamuddin is also occasionally diffident about his own abilities (‘[m]y life so far has gone by aimlessly, and so will what remains of it’ (52)). This appears to be false modesty, because later on he describes meeting the linguist, translator, and poet, William Jones (1746–94) at the University of Oxford, who ‘showed me many Arabic, Turkish and Persian works’ (52, 72). Jones was later to become a high judge in Calcutta and, as I’tesamuddin states, he had already written an influential Persian Grammar at the time of The Wonders of Vilayet’s publication. However, the Bengali claims that he taught the famous British scholar much of his knowledge about India. Some might suspect that I’tesamuddin is exercising the autobiographer’s privilege of exaggerating his own importance here, but this is actually an example of colonial appropriation of the native informant’s knowledge. The later traveller Abu Taleb’s similar belittlement of ‘Oriental Jones’ adds weight to the charge that he is something of an impostor. Additionally, in ‘Orientalism’s Genesis Amnesia’, Mohamad Tavakoli-Targhi shows that while Jones continues to be remembered as a giant in comparative linguistics, the contributions of Indian and Iranian scholars including I’tesamuddin to his research have been erased (1996: 3–8).

I’tesamuddin’s reception amongst the English is mixed: people have never seen an Indian wearing such opulent clothing, because they are only used to poorly-dressed lascars, so there is much gawking. He is even expected to dance for a group who mistake him for a performer. However, in time he claims to receive ‘great kindness and hospitality’ from the English and to be treated ‘like an old acquaintance’ (53–4). One of the most striking things about this book is the way in which I’tesamuddin constantly compares England to India, Bengal, or Calcutta, just as Nadeem Aslam’s later immigrant characters also translate northern England into subcontinental terms (Chambers, 2011c: 180–1). For example, I’tesamuddin reaches for the right words to praise London and comes up with the sentence, ‘Like Calcutta it straddles a river that falls into the sea’ (56).

A true tourist, he visits St Paul’s Cathedral, the Tower of London, Westminster Abbey, and an unspecified palace belonging to King George III, probably St James’s Palace.4 He describes the palace with a hauteur common to many upper-class Indians of the period, who compare British monuments, lifestyles, and customs with their Indian equivalents and find them wanting. To him, it is ‘neither magnificent nor beautiful’, and could easily be mistaken for the house of ‘a merchant of Benares’. He concedes that friends say the palace’s interior design is splendid, informing him that ‘the suites of rooms and the chambers of the harem are painted an attractive verdigris’ (59). In light of present-day Islamophobia, readers may find it comically incongruous that he uses the word ‘harem’ for George III’s private quarters and memorably describes Oxford University as a ‘madrassah’.5 When he visits the estate in front of the palace, complete with greenhouses, topiary, and further ‘lissom’ English women, he is moved to recall the couplet associated with the Mughal gardens of Shah Jahan:

If there’s a heaven on the face of this earth,

It is this! It is this! It is this! (60)

It is this! It is this! It is this! (60)

This Britain also has a gloomy aspect, as I’tesamuddin finds himself shocked at the divide between rich and poor (58–9), and describes Scotland as ‘a place where it is dark night for nine months of the year’ and where the ice crumbles ‘like so much papadom’ (66). In relation to this northern land readers are presented with the by now commonplace trope of the migrant’s first view of snow. I’tesamuddin describes snow as being ‘like abeer, the powder Hindus sprinkle on each other at the Holi festival, only instead of being coloured it is a brilliant white’ (76). With his images of ice cracking like poppadoms and the snow as powdery as abeer, I’tesamuddi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Note on Names

- Introduction

- Part I Travelling Autobiography

- Part II Travelling Fiction

- The Myth of Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index