eBook - ePub

South Africa's Renegade Reels

The Making and Public Lives of Black-Centered Films

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

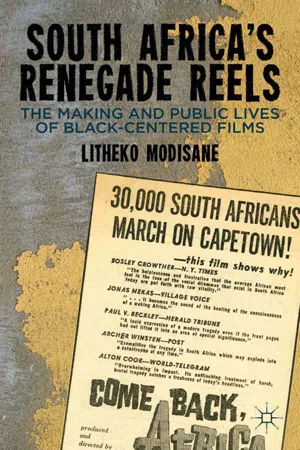

Despite incredible political upheavals and a minimal national history of film production, movies such as Come Back, Africa (1959), uDeliwe (1975), and Fools (1998) have taken on an iconic status within South African culture. In this much-needed study, author Litheko Modisane delves into the public critical engagements around old 'renegade' films and newer ones, revealing instructive details both in the production and the public lives of South African movies oriented around black social experiences. This illuminates the complex nature of cinema in modern public life, enriching established methodologies by expanding the cultural and conceptual boundaries of film as a phenomenon of textual circulation.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access South Africa's Renegade Reels by L. Modisane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Art General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

OPENING SHOTS

IN THE ARTIST GERARD SEKOTO’S FAMOUS PAINTING, Soka Majoka-Six Pence a Door (1946–1947), a group of young black women—one with a baby strapped on her back—curiously line up against the entrance of a makeshift yellow tent attached to a small house. We can only see their backs as their faces are pressed toward the tent, hidden from view. Children stand against the wall of an adjacent house and peep into the tent where a show is taking place. Other characters walk at a distance, indifferent to the attraction. The nature of the show is unclear to the viewer. However, Sekoto has offered a revealing explanation:

Our home was close to the playing ground which was in the centre of the township. On Sundays Zulu dancers would come and put up a tent. People would be eager to see inside but many would hang around outside with curiosity as they did not have the sixpence to spend. (Sekoto in Barbara Lindop 1995: 15)

Evidently, their poverty does not diminish the bystanders’ interest in the dance show. They stand outside to enjoy the thrill of being close to the show or perhaps to catch a glimpse through holes in the tent. Nor does it stop the Zulu dancers from taking full advantage of their cultural skills, which they duly monetize. The dance show is both an entrepreneurial activity, and a practical occasion for social interaction, not only for those inside, but quite decisively, also for those who cannot enjoy it firsthand. The fact that the bystanders are women adds, on its own, a distinct dimension of gender to the discourse of the painting. A welcome distraction, the dance show is a fraction of Sekoto’s depiction of the everyday life of 1940s Eastwood, the then black township outside Pretoria, South Africa, that he refers to in the above quote. The painting recollects a public scene of a marginal and improvisational modernity, in which the colonized create and access novel forms of commercialized leisure. Generally, the painting hints at the intersection between the social agency of urbanized blacks, the incipient money economy, and the making of marginal publics in a colonial setting. For the viewer, the painting is a glimpse of the formative stages in the evolution of commercial entertainment among the urbanized black South Africans.

In making the dance show the common denominator for the convergence of leisure and its material context, the painting offers a richly suggestive model of how film can be approached with a critical eye to its complexity not only as a signifying system, but also as an article with a public life. Drawing from the instructive lens of the painting, the space it frames, and the inconsistencies it foregrounds, we can begin to demarcate a cultural terrain in which film acquires significance as a site of the making of publics in colonial and apartheid contexts. Coming, as it did, a mere two years prior to the release of Donald Swanson’s African Jim (aka Jim Comes To Jo’burg) (1949), Six Pence a Door coincided with black South Africans’ first major involvement in commercial cinema. However, their entry into commercial cinema was not without key contradictions, a fact that, as will be seen, raises the issue of the critical value in the levels of correspondence between the content of film, and the material conditions of its circulation.

In this book, which foregrounds the publicness of a selection of black-centered films, I show the role of film in conjuring up a sphere of public critical engagements. By public critical engagements, I mean the public critical reflections—direct or indirect—that come into being in the wake of films or in anticipation of a film. Renegade Reels examines such engagements principally in relation to the theme of black identity, and to other themes flowing from such engagements namely: gender, sexuality, and violence. How these relate to the discursive sphere immediate to the films’ making and circulation forms part of the book’s analysis.

I have consciously identified the films as “black-centred” and not as “black,” because blackness is the subject of their focus, and not an a priori and hermetically sealed category. This book is concerned with the role of film in public critical engagements that at one time take the form of deliberation, and at others embodied but rational-critical activity. The core of the argument of South Africa’s Renegade Reels! is that under certain evolving conditions and circumstances of their circulation, black-centered films stimulate public critical engagements on blackness. Censorship, orchestration, context of circulation, and importantly, contextual affiliation to contemporary social and political preoccupations and relations, constitute the evolving conditions in the making and public lives of black-centered films. The convergence of these conditions with the generic and material attributes of film underwrites the precarious but potent status of film in the public life of ideas. It is potent because the possibilities for such engagements are enduring. I will explain this seeming contradiction more thoroughly in the course of the chapter. The restrictions imposed on Africans’ experiences of film in the early and late apartheid eras, and the changing public encounters with it in the emergent postapartheid period, provide the backdrop to South Africa’s Renegade Reels!

To write about film or the cinema from a perspective of its publicness, within a transhistorical context of colonialism, apartheid, and democracy must appear unduly contradictory to the reader. Not only do these periods signify substantively different political visions, but they are also marked by black South Africans’ significant lack of access to cinema. In its political form, at least within the liberal democratic tradition, the concept of the “public” presupposes a sphere of free political activity in which the state acts as a custodian of constitutionally protected rights, and not as a force of intimidation and the suppression of dissent. If we restrict ourselves to this understanding, we will see that to speak of publicness in inclusive terms is unhistorical, especially in the South African context.

If film is generally acknowledged to be an adjunct to the successive projects of colonialism and apartheid, how could it even be considered in the terms that appear to deny it its due historical place alongside the exclusionary politics of white minority governments? As a commodity, the cinematic apparatus—in South Africa—is historically affined to the racialized structures of monopoly capitalism. The formation in the postapartheid period of the National Film and Video Foundation, a statutory body charged with the national promotion and development of film has certainly gone some way in addressing inequities in the film industry. However, the cinema and the cinematic apparatus retain the legacy of racial and gender inequalities, both in terms of patronage, and ownership. But today, the inequality sits astride the uneasy marriage of democratic life and a triumphant liberal economy. Yet, neither democracy nor economic doctrines have monopoly over the reach of film or its consequent public effects. Access to film in cinemas, and in increasingly individuated spaces, suggests that its circulation is widely dispersed and likely to escape official surveillance. At the level of content, film may raise questions around contemporary social and political questions of its day, which may thrust it to the spaces of dominant politics and the marginal zones of potentially counterdiscourses. This book owes its inspiration to film’s dynamic fluidity, its capacity to sift through, over and across institutional rigidities. However, Renegade Reels! is not oblivious to the many challenges, themselves not static, which are attendant to black South Africans’ historical encounter with film.

AFRICAN ENCOUNTERS WITH FILM OR FILM ENCOUNTERS AFRICANS: A HISTORICAL SKETCH

A lack of symbolic control and ownership of African images by Africans themselves marks their historical encounter with film, in early twentieth-century South Africa. In this period, blacks were mainly constructed as “noble savages” “serving or killing white people” in movies that depicted frontier wars such as The Zulu’s Heart (1908) by D. W. Griffith, De Voortrekkers (Winning a Continent) (1916) by Harold Shaw, and A Zulu’s Devotion (1916) directed by Joseph Albrecht (Peterson 2000: 130).1 Other key fiction films of the period were Symbol of Sacrifice, (1918), and Allan Quatermain (1919). According to scholar and filmmaker, Bhekizizwe Peterson (2000: 130), with the emergence from 1927 of “authentic African documentaries” filmed by Europeans, a “deviation from the frontier features” occurred. For example, Africa Today (1927) by T. H. Baxter, “explored the impact of Western civilization on the native” (Peterson 2000: 130). However, the mining recruitment film, Native Life in the Cape Province, later changed to From Red Blanket to Civilization (1925), by one Henry Taberer, the African Labor adviser for Native Recruiting Corporation, precedes Africa Today. From Red Blanket includes reconstructions of African encounters with industrialization. In a recent study, historian Glenn Reynolds makes an interesting observation that “noticeably absent from the film are demeaning depictions of traditional life - what Rhodes once dismissed as the ‘life of sloth and laziness’” (Reynolds 2007: 136). However, its sequences are “constructed through a decidedly teleological and Eurocentric perspective” (2007: 136). In this period, black-authored or assisted productions were practically nonexistent.

As part of colonial society and later racist settler capitalism in South Africa, film became one of the objects around and through which the power relations that typified these societies were buttressed, both symbolically and socially. Deeply ingrained in these relations was the very iconography of Africa on screen. According to philosopher, Sylvia Wynter, the continent through the object of film, among others, “was submitted to the memory of the West” (cited in Givanni 2001: 29).2 In South Africa in particular, film was founded on the construction of colonial history that was in effect a celebration and validation of the violence that led to the subjugation of Africans. Although its primary context is colonial Zimbabwe, historian James Burns’s work, Flickering Shadows: Cinema and Identity in Colonial Zimbabwe (2002), offers some insights into the mobilization of cinema in pseudoscientific colonial enterprises. Burns shows that from the late 1920s, white scholars began to do research that cast aspersions on Africans’ ability to understand cinema. According to him, “settler fears that Africans were incapable of understanding cinematic images became entangled in a broader debate about African ‘difference’, a discussion that held a crucial relevance for white politics in Southern Africa” (Burns 2002: 3). Arriving in Southern Africa in early twentieth century “when fundamental assumptions about the nature of African intellect, and the identity of white society were undergoing a process of reformulation” (Burns 2002: 2), film became an important instrument in the instating of the idea of white superiority, and therefore, the legitimacy of white people to rule over black people.

Awake to the ideological significance of cinema on the Africans’ social and political imaginary, the African elite challenged the negative portrayals of Africans in cinema. Author, Secretary-General of the South African Native National Congress (SANNC)3, and its founding member, Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje, registered his doubts about the cinema.

I have since become suspicious of the veracity of the cinema and acquired a scepticism, which is not diminished by a gorgeous one exhibited in London which shows, side by side with the nobility of the white race, a highly coloured exaggeration of the depravity of blacks. (Plaatje cited in Willan 1996: 212)4

Plaatje was responding to the racist film, Birth of a Nation (1915), particularly the crucifixion scene in which a white actor in black paint plays the ill-famed biblical character, Judas Iscariot. According to his biographer, Brian Willan (1996), Plaatje and his confederates successfully protested against the film’s exhibition in South Africa. The protestations against the film are instructive with regard to the place of cinema in the political public life of South Africa. It can be intimated from these protests that the cinema’s relations with colonial modernity, were in this early period, predicated upon contestations over black identity, particularly its role in the battle for ideological supremacy between African intellectuals and colonial ideologues. From the vantage point of his own efforts with the cinematograph, it seems that Plaatje’s vigilance against Birth, among other plausible causes, inspired in him the need for counternarratives to white supremacist representations. In November 1923, Plaatje brought documentary films from his trips in the United States to black South African audiences (Balseiro and Masilela 2003: 19–20).5 The films, whose titles are unfortunately not recorded, were acquired from different sources. What he reportedly called the “topicals” were donated by Mr. Henry Ford, the automobile manufacturer. “Negro industrial films were given him by Dr. Moton of Tuskegee, while the English and South African pictures were a gift by Mr. I. R. Grimmer of Kimberly” (Umteteli wa Bantu article in Balseiro and Masilela 2003: 19). According to film scholar, Jacqueline Maingard, Plaatje’s acquisition of part of his “bioscope” apparatus, a portable generator, was not without irony. De Beers, the diamond mining company, had donated it (Maingard 2007: 68). With his mobile bioscope, Plaatje managed to reach remote parts of the country, and set in motion “the entry of black South Africans into the world of cinema audiences” (Maingard 2007: 68). But the audiences of his film exhibitions were not restricted to black people. Ntongela Masilela writes that the idea behind Plaatje’s efforts was to impress upon Africans, the achievements of “New Negroe” intelligentsia in the areas of education, agriculture, and industry. Masilela also ascribes Plaatje’s bioscope to the vision of the New African Movement intellectual elite of which he was a “member” (Balseiro and Masilela 2003: 15–30).6 According to Masilela, the New African Movement emerged in the post–Anglo-Boer War years and ended with the Sharpeville massacre of 1960. Influenced by the attainments of African Americans—the so-called New Negro Intelligentsia—its thinkers, Masilela observes, were generally preoccupied with the construction of modernity for Africans, and used outlets such as the newspaper Umteteli wa Bantu (the Mouthpiece of the People) (in Balseiro and Masilela 2003: 15–30). The cinema became a new, though not widely available outlet, for the New African Movement’s aspiration of a new modernity for Africans.

Plaatje showed features and shots of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama, drills at the institute, and Negro spirituals as well as footage of the weddings of Sir Seretse Khama and the Duke of Westminster.7 Plaatje’s mobile bioscope demonstrates that Africans’ encounters with cinema were sometimes influenced by the exhibitionary practices of early American cinema.8 These practices involved the showing of silent films to the accompaniment of a full music band, and a soloist (Plaatje’s son St. Leger), as well as a lecture by Plaatje himself.9 These exhibitionary practices are in keeping with film scholar Miriam Hansen’s description of early cinema in the United States, which I will discuss in due course. Interestingly, she argues that these practices are central to the “alternative public sphere” constituted by early cinema.

Maingard observes, in a recent study, that Plaatje’s bioscope constitutes the beginning of a national alternative film culture (2007: 5). Plaatje’s introduction of cinematic ways of engagement with black identity was alternative, because it was not in keeping with South Africa’s mainstream cinematic culture. In South Africa, “cinema, until the 1950s, was targeted, almost exclusively, at white audiences” (Peterson 2000: 127). Therefore, Plaatje’s bioscope constituted a relatively autonomous space of construction of black identity and publics against the racially exclusionary colonial film culture.

Plaatje’s efforts suggest that a rapport and identification with modernity lay at the center of black South Africans’ early encounter with the cinema, as represented by the images of English and Tswana royal matrimonies, and the activities at Tuskegee (an African American college). The Africans’ encounters with cinema coincided with their aspirations of accessing modernity and its promising fruits of “progress.” In relation to cinematic culture in general, “the spread and popularity of cinematic screenings among Africans can be traced to the early 1920s” (Peterson 2000: 127–128). However, a regime of heavy censorship attended the films shown to Africans, “firstly by the Cape Town Board of Censors and secondly, by Dr Phillips and later a special board appointed by the Native Recruitment Agency” (Gutsche 1972: 378–379). Low wages and low viewing charges prevented the development of cinemas among Africans, at least until the 1940s (Gutsche 1972: 379, 385).

The representation of black identity was key to the colonial apparatus of political legitimation. It is precisely because of the centrality of black identity in Africans’ troubled encounters with film, that this book highlights films’ engagements on black identity. While I accept that blackness or African identity is a historical problematic, constructed and reconstructed in varied ways over time, I approach blackness or black identity in terms of heterogeneous cultural and political constructions with which people of African descent, and variously people of colour with generally similar historical experiences of modernity, identify. Such constructions are premised on a negotiation of modernity and a resistance of its contradictions—racial prejudice in particular and negative stereotype...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Opening Shots

- 2. From Africa to America, and Back Again: Come Back, Africa (1959)

- 3. Propagandistic Designs, Transgressive Mutations: uDeliwe (1975)

- 4. Engagé Film and the Public Sphere: Mapantsula (1988)

- 5. Gender in the New Nation: Fools (1998)

- 6. Orchestration of Debate through Television Drama: Yizo Yizo (1999, 2001)

- 7. Closing Shots

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index