eBook - ePub

Urban Identity and the Atlantic World

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Identity and the Atlantic World

About this book

The constant flow of people, ideas, and commodities across the Atlantic propelled the development of a public sphere. Chapters explore the multiple ways in which a growing urban consciousness influenced national and international cultural and political intersections.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Urban Identity and the Atlantic World by E. Fay, L. von Morze, E. Fay,L. von Morze,Kenneth A. Loparo,Leonard von Morze, E. Fay, L. von Morze, Leonard von Morze in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Social History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

SPATIAL PROJECTIONS OF POWER

1

ATLANTIC URBAN TRANSFERS IN EARLY MODERNITY

MAZAGÃO FROM AFRICA TO THE AMERICAS

MOTTO

The history of the Portuguese city of Mazagão is also the history of a journey over the Atlantic. Figuratively speaking, this chapter is structured as a ship’s voyage from the northwestern shore of Africa to the Amazon basin rain forest to follow the Portuguese contribution to the urban design and public space from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries along the coasts and islands of the Atlantic Ocean. Established as a castle in 1514 and confirmed as a fortress town a few decades later, Mazagão had its population relocated to South America in 1769. Chronologically speaking, both original and subsequent urban plans in the different sites delimit Portuguese early modern experience as far as the evolution and the establishment of regular geometries to the city fabric are concerned.

A SETTLEMENT IN AFRICA

Hypotheses of prior occupation of Africa’s northwestern coast are vague for the region where Mazagão was established until the end of the fifteenth century. Probably a small fishing port and village existed in a place called Mazgan, compelling the idea of an almost inhabited place before the arrival of the Portuguese. Today, the Boreja or Bridja tower, which belonged to a series of watch posts along the coast, seems to be the only remaining evidence from that period. In the beginning of the sixteenth century, the Portuguese had already begun to conceive of erecting a small castle in the vicinity. However, only after the conquest of the neighbor town of Azemmour (15 kilometers north) in 1513, did the Portuguese finally establish a castle at the site of the former round tower the following year. Two renowned master builders and brothers, Diogo and Francisco de Arruda, composed a quadrangular plan with wall curtains linking four cylindrical towers,1 one of them being the primitive Boreja.

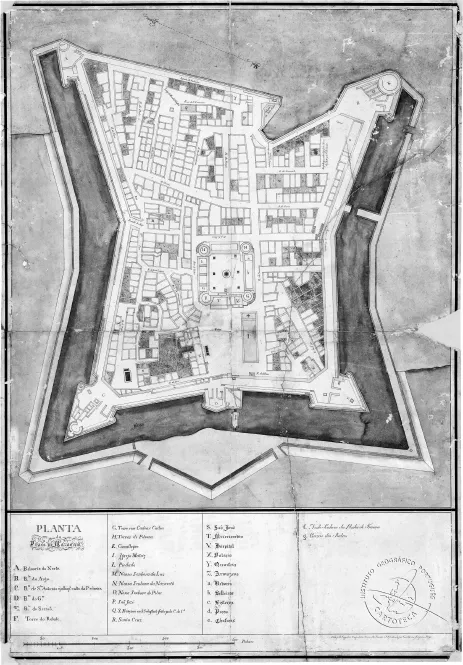

In 1541, the loss of Santa Cruz do Cabo de Guer, present-day city of Agadir, to the conquering Saadi Cherif destabilized the Portuguese enterprise, and eventually caused the abandonment of several other Portuguese cities in the region. The same year, the Portuguese decided to invest in a new settlement that would be a modern bastioned fortification with the establishment of a grid plan designed town in its interior. Mazagão, as it was designated, provided a solution to keeping some presence in the Moroccan southern geographical arch. The royal initiative was managed by a team of architects and military engineers led by Benedetto da Ravenna, Diogo de Torralva, and Miguel de Arruda and put into practice on the site by João de Castilho.2 For more than two and a half centuries, the impregnable Mazagão remained in Portuguese control due to its fortified perimeter defined by five big bastions, long inflected wall curtains, and a surrounding moat as the Planta da Praça de Mazagão illustrates in figure 1.1.

The location of the previous 1514 castle, now transformed into administrative headquarters in order to house a church, a hospital, storehouses for cereals and munitions, a jail, and a huge water reservoir, seems to have worked as a generatrix of the urban space of the projected town in 1541.3 To the west, a big public square was defined by the governor’s palace, the town gate, and main thoroughfare, Carreira street, representing the negative space of the surface occupied by the former square castle. Indeed, this quadrilateral building, measuring between 53 and 57 meters (approximately 26 braces), launched the diagonals that would define the position of the new fortified bastions, with the exception of São Sebastião (San Sebastian). It would also provide the metrical base for the grid planning of Mazagão. Regular blocks derived from the subdivision of the central square model in half-rectangular portions.

The model is close to the one applied to the Portuguese city of Daman in India years later.4 In Daman, each unit was identified as the result of the subdivision of the primitive castle in four parts. However, in Mazagão, the model was applied to focus on rectangles rather than squares, and it was used less inflexibly in the African city. Indeed, a regular pattern based on rectangles is observable only in southern and eastern areas of the walled perimeter, thus not covering the whole surface due to adjustments made for irregular contour. Although this created its own difficulties from directional variance, nevertheless, the tendency toward geometrized configurations of the urban display in Mazagão was one of a greatest advance in urban design so far.

Figure 1.1 Planta da Praça de Mazagão—Simão dos Santos / Guilherme Joaquim Pays [c. 1760], Instituto Geográfico Português (IGP), Lisbon.

The year 1769 marks the evacuation of the town due to problems in military sustainability after yet another siege by Sultan Sidi Mohamed ben Abdallah. The departure ordered by the Marquis of Pombal, in Lisbon, led to the strategic destruction of part of the walls and bastions in preparation for complete evacuation. Explosions were used to disable the citadel for appropriation by the besiegers. Two thousand inhabitants were transported to Brazil, where Vila Nova de Mazagão (New Mazagão) was settled.5

Al-mahdouma, meaning “the destroyed,” was the local denomination for Mazagão after the Portuguese abandonment. For almost half a century, the once-Christian stronghold, now considered as unfaithful, was uninhabited, accentuating its ruined state. Eventually, after the 1820s reconstruction, mellah became the designation for the walled area, which was first occupied by the Jewish community. By 1861, descriptions mention 1,500 inhabitants divided into foreigner, Arab, and Jew populations, showing that the reconstructed fortress started slowly to house religious buildings of different creeds such as a synagogue and a mosque.6 The stronger symbol of this ecumenical atmosphere was the replacement of the former Rebate tower, one of the four corners of the Portuguese primitive castle, by a minaret.

During the French protectorate (1912–56), this fortified neighborhood was called Cité Portugaise, a name that invoked the Portuguese past, in a clearly French colonial effort to enhance its European roots, heritage, and culture. Eventually, mellah and Cité Portugaise remained as the denominations by which this citadel is known today within the city of El Jadida, “the new one.” In the twenty-first century, the citadel represents a backwater quarter although it remains densely populated with more than three thousand residents, many of them living in basic conditions. The center of the city has moved outside to the “medina” area formed from the nineteenth century onward (see aerial view of the city in figure. 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Aerial view of Mazagão, 1923. Département du Patrimoine Culturel, Ministére de la Cuture et de la Communication, Rabat.

Today, nearly two and a half centuries after the Portuguese evacuation, one can observe daily changes in Mazagão’s urban fabric. The original orthogonal plan has been suffering an “islamization” process: streets are interrupted or shortened, alignments become inflected, and broad perspectives are replaced by privacy and shadow.

TRANSFERRING A TOWN TO THE AMERICAS

After this 250-year period, another urban history was taking place in a homonymous town in South America. Retaining the same African name of Mazagão signaled a clear reference to a memory of conquests and a glorious past that the crown, through its Pombaline administration, thought it crucial to convey to a region under dispute by several European powers, the French being the closest rivals with their establishment in Cayenne around 1676.7 Mazagão, together with its neighboring, more important town of Macapá, would assure consolidation of the Portuguese northern territories in the continent, a dispute only completely sorted out with the Iberian rival, the Spanish crown in 1750 by the Treaty of Madrid.8

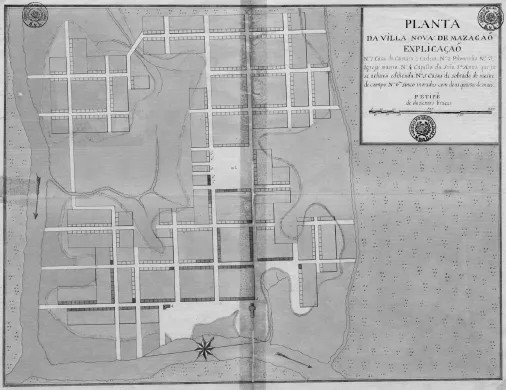

Domingos Sambucetti, an engineer of Italian origin, together with Captain Ignácio de Castro de Moraes Sarmento, formed the pair responsible for the establishment of this new town over an indigenous site called Santa Ana do Rio Mutuacá. See the Planta da Villa Nova for this new town in figure 1.3.

The urban plan shows a grid pattern of quadrangular units of 56 braces, 4 braces for the width of each street and, consequently, 64 braces for the open squares.9 However, houses would only occupy two sides of each block, allowing different combinations and encouraging dynamic compositions. The plan was disposed according to intercardinal directions and incorporated only the chapel of the former indigenous village.10

The population non-resilience to the transfer from Morocco to South America was an early sign of the condemned future of this new establishment. The “rebuilt” and “reformed” New Mazagão soon suffered from critical climate and public health issues, the most common problems being flooding and malaria. From 1783 onward, another removal was increasingly debated, and during the nineteenth (after Brazil’s independence) and early twentieth centuries, New Mazagão became progressively “Old Mazagão” (Mazagão Velho) with yet another “New” town being settled along the road toward Macapá, the state capital of Amapá, in northwest Brazil.

Figure 1.3 Planta da Villa Nova de Mazagaõ [sic], 1770. Arquivo Histórico Ultra-marico (AHU), Lisbon.

The urban mark left by Vila Nova de Mazagão and São José de Macapá, is for both the structuring matrix of the grid with its filled or empty square units that constitutes the city’s core and allows for its urban present expansion.

THE NORTH ATLANTIC TRIANGULAR EXPERIENCE

A question emerges: How can both African and South American settlements be related since their original planning is separated by more than two centuries? Indeed, no direct connection should be undertaken in that sense, even though both are characterized by a grid matrix and New Mazagão shows propensity to double the sixteenth-century African plan dimensions. Nevertheless, this urban transfer across the Atlantic allows us to extrapolate notions of public space organization because the geographical translation and historical interval involved are consistent with early modern Portuguese urban experience.

Notions of regularity have been present in the Iberian Peninsula long before the sixteenth century. Roman occupation provides the foundation of several grid-planning cities.11 Along the Santiago Path in the low Middle Ages, for example, the establishment of some bastide...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Series Introduction : “The New Urban Atlantic”

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I Spatial Projections of Power

- Part II The Site of Reform

- Part III Identity and Imaginative History

- Part IV Cultures of Performance

- Bibliography

- List of Contributors

- Index of City Names

- General Index