eBook - ePub

Women's Cricket and Global Processes

The Emergence and Development of Women's Cricket as a Global Game

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Women's Cricket and Global Processes

The Emergence and Development of Women's Cricket as a Global Game

About this book

How can the diffusion and development of women's cricket as a global sport be explained? Women 's Cricket and Global Processes considers the emergence and growth of women's cricket around the world and seeks to provide a sociological explanation for how and why the women's game has developed the way it has.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Women's Cricket and Global Processes by Philippa Velija in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Feminism & Feminist Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Women’s cricket is a global game that has had an international governing body since 1958. There are an increasing number of global competitions and at present the women’s game is represented in the same national and global organisations as men’s cricket, although this has not always been the case. Recently ten countries participated in the women’s T20 World Cup in Bangladesh, and some female cricketers were paid to represent their countries. International tournaments and bilateral competitions are increasing and international cricket is now a year-round operation. This suggests that women cricketers are a visible, albeit marginal, part of the global game. In the introduction to Women’s Cricket and Global Processes: The Emergence and Development of Women’s Cricket as a Global Game, I start by drawing on three recent examples that highlight the changes in women’s cricket as a global game, thus charting out the aims of the book and the key theoretical perspective that underpins the analysis of women’s cricket as a global game.

The first example is the women’s Ashes. At the time of writing this book, the England women’s cricket team won the 2014 Ashes series in Australia. ‘The Ashes’ remain one of cricket’s most prized achievements for English and Australian cricketers and the series continues to have importance and be related to ideologies of national pride and success of the ‘nations’, reflecting their social history and identity. The women’s series has only been called the Ashes since 1998 despite matches between Australian and English women dating back to 1934, when England travelled to Australia for the first international women’s cricket match. Rachael Heyhoe Flint, one of the most well-known female cricketers, describes how the women’s Ashes were considered by players as being of great significance: ‘The aura of the Ashes and the lure of battles against the enemies from down under outshine anything else the game can offer’ (1978: 72).

The intense competition in the Ashes between the England and Australian men’s teams continues to generate extensive media interest. In Australia, the Ashes symbolise a battle between the two nations that evokes images of national identity and masculinity (Stevenson, 2002). In the 2013–2014 series, the England men’s team lost the series 5–0. In contrast, the England women’s team won their series, and this was only the third time that this had been achieved on Australian soil. The women’s Ashes is played in a format different from the men’s; it is a multi-format series comprising one test match, three one-day matches and three T20 matches. The format provides six points for a test match win and two points for a win in each of the one-day and T20 formats. This variation is significant as it lessens the emphasis on the test match win and symbolises a key difference in the women’s game: test match cricket remains marginal in women’s cricket. The format for the women’s Ashes has also often changed – for example, through the initial Ashes series, from 1934 to 1984, women played three test matches as standard; since 1984, the format has switched from five to just one test match in 2007 and 2009. For the men, the Ashes are decided through the traditional format of five test matches which has not changed throughout the history of the series.

In England, the 2013–2014 men’s loss was subject to hours of media critique, with headlines such as ‘England should feel ashamed and embarrassed by the Ashes defeat’ (The Telegraph, 5 January 2014), ‘Ashes whitewash was an implosion like no other in English history’ (The Telegraph, 5 January 2014), ‘Australia complete Ashes whitewash’ (BBC, 5 January 2014) and ‘It’s a whitewash! Sorry England embarrassed by Australia after another humiliating defeat Down Under as hosts complete 5–0 rout in Sydney’ (The Daily Mail, 5 January 2014). The focus on humiliation and the link to English history illustrates the relationship between sport and national identity. The loss of the (men’s) England cricket team has often been linked to broader issues of national pride, for example, losing to India and Sri Lanka in the past has been linked to ‘English Shame’ (Maguire, 2012: 152). Terms such as shame and humiliation are drawn upon to indicate a broader sense of loss as a nation. Research has focused extensively on how sport can be a medium through which people identify with the nation; however, much of this research focuses on the relationship between men’s sport and national identity (Mansfield and Curtis, 2009). Scholars within the sociology of sport have identified how sport is part of people’s identity and specifically their national identity (Liston and Moreland, 2009), but less research has considered the relationship between gender the nation and national identity. Much research has identified how there is a strong relationship in the main cricketing nations, and the diaspora, between cricket and national identity and the recognition that cricket can reflect (or reinforce) how people think of themselves and ‘others’ (Malcolm, 2012). Again, this research often does not consider how women also identify with the nation through supporting (men’s) cricket and to date there is no research that explores whether women’s cricket reflects national pride, character and identity in the way that men’s cricket does.

Women are part of the ‘nation’, but their sporting success does not necessarily evoke feelings of national identity in the same ways that men’s sport does. The success of the England women’s team in the Ashes was reported on by the media, illustrating a significant shift in gender relations in which women’s sport is no longer ignored. Although this was marginal, media coverage about the women’s success focused on how the women’s team could restore ‘national pride’ after the loss of the men’s team. For example, The Telegraph claimed that another ‘English Ashes assault could not be in safer, stronger hands’ (8 January 2014). The increased media attention in the women’s game marks a shift in power relations between men’s and women’s cricket. Furthermore, while the Telegraph article suggests that the women’s game could reflect pride and national identity, media coverage remains so slight that few people are aware of the losses or successes of the women’s national team in any nation where the game is played.

Women’s cricket, although developing as a global game, is not drawn upon to evoke strong feelings of national identity and pride in the way that men’s cricket is. In addition, the women’s game is largely dependent on the men’s game for its development and support (more so since the mergers discussed in Chapters 4 and 5), especially for financial support. Women’s cricket has not received much academic discussion, although the history and development of men’s cricket as a national and global sport (see for example Bose, 2006; Gemmell, 2004; Majumdar, 2003; Malcolm, 2013; Nauright, 2010; Sandiford, 1998) has been subject to discussion in several academic texts. In these accounts, the women’s game is largely invisible. Some establishment accounts of women’s cricket exist – Joy’s Maiden Over: A Short History of Women’s Cricket and a Report of the Australian Tour 1948–49 (1950), Heyhoe Flint and Rheinberg’s Fair Play: The Story of Women’s Cricket (1976) and more recently Duncan’s Skirting the Boundary: A History of Women’s Cricket (2013) – and give us some details about the history of the women’s game. However, these accounts do not offer an explanation for the emergence and development of the global game, considering how social processes and power relations influence the development of women’s cricket. Women’s Cricket and Global Processes: The Emergence and Development of Women’s Cricket as a Global Game therefore adopts a sociological approach to explain how and why cricket for women emerged and developed and significantly how power relations between men’s and women’s cricket influence the social habitus of women who play cricket.

Women’s cricket: A global game

The second example also reflects a significant shift in power relations in the women’s game. On 1 February 2013, the Sri Lankan women’s team beat England at the World Cup during a group stage match. The importance of this win to the Sri Lankan team was highlighted by the Sri Lankan captain Shashikala Siriwardene, who described the win as the finest in her team’s history: ‘It’s like a dream come true for us. We’ve been waiting for this moment for 16 years’, she said. Why is beating England so important to Sri Lanka? It no doubt reflects the colonial position of cricket more broadly; beating England is associated with bringing pride to many ex-colonies, as beating the masters at their own game has an important role to play in shaping national identities and the national characters of those who follow cricket. However, what does it mean for Sri Lankans in the context of women’s cricket? Acceptance? Reflection of an international standard? Undoubtedly England is at the heart of the development of women’s cricket as it represents the emergence of women’s cricket globally. It was the first country with a national governing body, it was at the forefront of the development of the International Women’s Cricket Council (IWCC) and, having won a number of international tournaments, the England women’s cricket team reflects the established group within women’s cricket. Beating England demonstrates a suitable ‘global’ standard of play, but this emotive response by Sri Lanka indicates two key issues:

a) | it further questions the role of gender, national identity and women’s cricket and the extent to which women’s sport can reflect national character and pride, and | |

b) | it demonstrates the growth of the women’s game and increased competitive standards of the global game, in which previous minority countries are starting to challenge and beat other ‘established’ teams. |

Significant changes in the structure and governance of women’s cricket occurred in 2005, when the women’s game merged with the existing International Cricket Council (ICC). Prior to this, from 1958, women’s cricket was governed by the IWCC. The merging of men’s and women’s cricket organisations is a trend that has also occurred in the national governance of the game. This was reinforced as part of the ICC mandate in which all countries that had separate men’s and women’s cricket boards had to merge the two to create one governing body that represented all elements of the game. In some instances, this mandate was enforced on national governing bodies, whereas in England, Australia and New Zealand, the mergers took place before the ICC mandate.

With the merger between the IWCC and the ICC, the women’s game came under the governance of the ICC, which has a history of developing and organising the global men’s game since 1909. At present, as at the time of the merger in 2005, the ICC has three membership categories – Full, Associate and Affiliate. There are ten full members of the ICC: Australia, Bangladesh, England, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, West Indies and Zimbabwe. According to the ICC, the full membership category is for the governing bodies of cricket that are from

a country recognised by the ICC, or nations associated for cricket purposes, or geographical area, from which representative teams are qualified to play official Test Matches. (ICC, 2013)

This definition does not mention women’s cricket. Full membership is decided in relation to the status of men’s cricket and more specifically test cricket. This is based on historical issues that enabled men’s cricket to develop in specific ways. In women’s cricket, test match cricket is rarely played, which is why the Ashes are not decided over a series of five test matches. Test match cricket has not played a significant part in the recent development of the game and some full member countries, such as Sri Lanka and Pakistan, have played less than five test matches in the last 18 years. Some of the problems associated with test match cricket for women are as follows: the length is not compatible with amateur female cricketers’ schedules and the lack of competitiveness amongst some nations has meant that test match cricket has not played a significant part in the development of women’s cricket, in the way it has in men’s cricket. Having test match cricket status is not a reflection of standard in the women’s game. Although all the full members were awarded ICC membership prior to 2005, and the merger with women’s cricket, the criteria for full membership have not been reviewed and only eight of the ten full members played in the 2013 women’s World Cup. Moreover, the dominance of certain teams is evident through looking at, for example, the women’s World Cup. Since 1973, Australia has won six, England has won three and New Zealand has won one title.

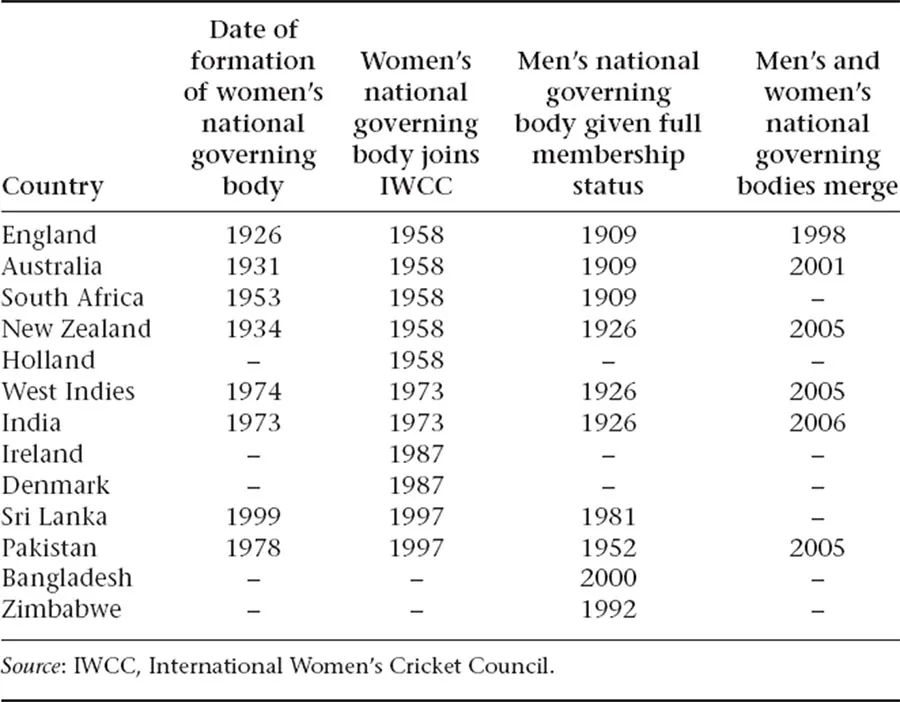

The ten full members of the ICC and the dates on which they received full membership reflect the diffusion and development of men’s cricket. Yet, the women’s game has had a different trajectory of development than the men’s game. As demonstrated in Table 1.1, the women’s game started to follow a similar trajectory to men’s cricket, but as the women’s game developed, Holland and other European countries such as Ireland became influential in the women’s global game. These countries went on to compete in the recent 2014 T20 World Cup. In contrast, Sri Lanka and Pakistan did not play international cricket until the 1990s. These patterns of diffusion are discussed throughout the book, specifically in Chapter 3, to consider the development of women’s cricket and in discussing how these patterns may reflect broader social processes, gender relations and power.

Table 1.1 Significant dates in the global development of men’s and women’s cricket

As the table demonstrates, women’s cricket does not completely mirror the development of men’s cricket. The social processes involved in the development of women’s cricket need to be considered and explained, and this is in part the aim of Women’s Cricket and Global Processes: The Emergence and Development of Women’s Cricket as a Global Game. To do this, figurational sociology is adopted as a framework for explaining the development of women’s cricket and power relations that have impacted on the emergence and continual development of women’s cricket as a global game.

Women’s cricket, social identities and women as outsiders in the global game

The third example says something about the women’s game and the habitus or identities of those women who play the game and the response of others. On 14 January 2013, Sarah Taylor, an England cricketer, was on the front page of The Guardian (a British daily newspaper): the article was about her playing Second XI county cricket in the 2013 season. Nothing unusual about this you might think, other than women cricketers do not often appear on front pages of newspapers for playing cricket and this article was actually about the possibility that she might play men’s cricket. In the interview in The Guardian, Taylor herself suggests that such a prospect is ‘daunting’ and that playing in the men’s Second XI team, as a wicketkeeper, would be a challenge. In particular, she stresses how she would be facing a ‘bigger ball and bigger bowlers’ (Taylor, cited in McRae, 2013); adding to this, she needs to ask herself, ‘Can you handle this?’ The reference to a bigger ball and bigger bowlers is interesting as it raises the usual responses in the media discussions, drawing on ideas of men’s sport being bigger, better and more of a spectacle than women’s sport. These debates are not just discussed in public forums and in debates about men and women’s sport, but Taylor herself questions whether she can ‘handle’ the men’s game. Although the level that Taylor is proposing to play at in the men’s game is...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Cricket and Masculinity in Early Forms of Cricket

- 3 Civilising Processes, Gender Relations and the Global Women’s Game

- 4 Women’s Cricket, International Governance and Organisation of the Global Game

- 5 Cricket and Gendered National Identities: The Experiences of Women Who Play and Organise the ‘Global Game’

- 6 Conclusion

- References

- Index