eBook - ePub

Gender, Race and Family in Nineteenth Century America

From Northern Woman to Plantation Mistress

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gender, Race and Family in Nineteenth Century America

From Northern Woman to Plantation Mistress

About this book

Sarah Hicks Williams was the northern-born wife of an antebellum slaveholder. Rebecca Fraser traces her journey as she relocates to Clifton Grove, the Williams' slaveholding plantation, presenting her with complex dilemmas as she reconciled her new role as plantation mistress to the gender script she had been raised with in the North.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gender, Race and Family in Nineteenth Century America by Rebecca Fraser in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Modern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

“Everything Here is So Different”: Changing Cultural Landscapes

I feel confused everything here is so different that I do not know which way to turn for fear of making a blunder.1

When Ben brought his new bride home to Clifton Grove in September 1853, the marriage had raised many an eyebrow among Sarah’s New Hartford neighbors, friends and family. New Hartford village, where the Hicks family home was, is located in the town of New Hartford in the county of Oneida, central New York State. Founded in 1789 by Jedediah Sanger, the village had demonstrated some remarkable transformations in terms of its economy and industry in the years following the American Revolution through the beginning of the Civil War in 1861. The wealth of the town developed rapidly owing to Sanger’s keen involvement in the purchase of turnpike company stock, which allowed him to hold some influence in determining location and routes. While the opening of the Erie Canal in October 1825 did much to move New Hartford’s trade toward the county seat of Utica, the village retained the use of water power with Sauquiot Creek and thus remained a presence in the emerging industrial boom of the Northern States.2 In Utica, industries such as textiles and paper manufacturing dominated the economic landscape alongside the continued existence of artisans and smaller craftsman, in addition to a sizeable number of those employed in white-collar occupations such as managers, clerical workers and shop assistants. As Mary Ryan underlines, antebellum Utica was characterized by “rapid population growth, a high level of transience, voluminous social mobility (in upward, downward, and horizontal directions), and a massive influx of immigrants from abroad.”3 Such was the world that Sarah had left behind to marry Benjamin Williams and relocate to the pinelands of North Carolina.

Sarah’s departure, so far away from her family home, went against the typical behavior for young women from Oneida County, while her motives for leaving were met with extreme disapproval in a region that had been the centre of evangelical revivals of the 1820s and had played host to a strong antislavery movement ever since.4 Nevertheless, as Sarah reflected on the reaction to her move, she hoped that her kith and kin had found it in their hearts to have “buried the unkind feelings ere this. I can assure you I cherish no hard feelings toward them. I still think their course mistaken for my Bible tells me that ‘Charity suffreth long & is kind.’ And even our Saviour could eat with publicans and sinners.”5 Yet Sarah herself had initially found it difficult to reconcile her growing affections toward Benjamin Williams with his status as a slaveholder. Their courtship had lasted eight years and despite repeated proposals of marriage on his part, Sarah remained steadfast in her refusals suggesting that “[t]here are but two things that I know of to dislike in the man. One is his owning slaves. I cannot make it seem right. … The other is not being a professing Christian.” Although she found Ben’s ownership of slaves troubling she resolved, following her eventual acceptance of the invitation to be his wife in the spring of 1853, to make the attendance and care of his slaves her “sphere of usefulness.”6

It must have been easier for Ben to have impressed Sarah in the first year of their courtship, when they had met as fellow boarders in 1845 at Mrs. McDonald’s residence, 66 North Pearl Street, Albany, where they were both staying while studying at the academy. Ben was training as a physician under Dr. McNaughton, while Sarah was attending the Girl’s Academy, receiving an education that went beyond the standard provided for women of this era. The academy included in its higher department, studies in basic and ecclesiastical history, French and Paley’s moral philosophy, which were of course, “suited to the character and condition of females.”7 Sarah’s assessment of Ben as a “fit and moral young man” must have reassured her parents, safe in the knowledge that this boarder was indeed a gentleman, being the uncle and brother of two of Sarah’s classmates. Nevertheless, these assurances must have been tempered by the revelation that she suspected that her brother-in-law, James, “would not like them very well” as the Williams between them owned 300 slaves.8 Far removed however from the pressures that this young couple both would have undoubtedly felt in their respective homes if their relationship had have begun there, they no doubt enjoyed the freedoms provided through living as boarders at Mrs. McDonald’s lodgings on Pearl Street in the heart of the city of Albany.

Sarah was 26 years old when she married Ben: an average age of female marriage among the population of antebellum New Hartford. Yet this was certainly not in line with the ideals of wealthy North Carolinians of this era, where women from the planter class typically married six years earlier.9 Benjamin, at the age of 33 when he wed, must have been perceived by his North Carolinian contemporaries as a fairly old bachelor given that the average age of marriage for planter class men was 24. His choice of a Northern bride must have also been met with surprise and slight unease by many of his family, for it was considered the norm for members of the North Carolinian slaveholding elite to marry within their own class and from within their own county. This practice not only helped to cement familial alliances, but also reaped the rewards of Southern brides’ dowries in the form of property, including land and slaves.10 Nevertheless, Ben had proved his devotion to Sarah by waiting eight years for her to accept his proposal, and as she reflected “[this] is long enough to test friendship, and such fidelity is seldom met with in this world, and is sufficient to cause me some serious thought.” Benjamin’s persistence and unwavering commitment in the face of rejection eventually softened Sarah’s feelings toward him and she reflected that “his affection for me has outlived so many reverses” that she could not help but “respect the man most highly.”11

Clifton Grove, the Williams’ plantation and Sarah’s marital home for the next four years, was secluded in the pine lands of Greene County. The area is located in the Central Coastal region and although a small county, as James Bonner points out, “it is one of the richest agricultural areas in the state.” The plantation itself was separated from Snow Hill, the county seat of Greene, by the northern branch of the Neuse River, bordering the plantation on the southern side for five or so miles. Ben’s share of the plantation was vast, covering over two thousand acres of land. This acreage was divided between cultivated cotton and subsistence, which amounted to seven hundred and fifty acres and which Sarah assumed were worth between 12 and 15 dollars an acre. The remaining 1400 acres were devoted to pine land averaging “from 3 to 5 dollars per acre” with 73 additional acres at Sandy Run, around seven miles from Clifton Grove. The pinelands were all worked for turpentine. The extent of land owned by Ben and his mother then, as co-beneficiary of her late husband’s Will, was extensive and the labor of at least thirty-seven enslaved peoples at Clifton Grove alone, not to mention those at the turpentine farm seven miles away, ensured the Williams’ a healthy profit in return.12

The Williams were well respected members of the planter class in Greene County during this era. Ben had been elected as a member of the State legislature from 1850–1854, thus reinforcing his own claims to respectability and gentility in the local community, in addition to enhancing his reputation at the state level. The Williams’ standing in Greene County was born from a longstanding association with other local planters and intimate family connections in and beyond Greene which firmly rooted them in the slaveholding South as part of the elite planter class. Ben’s youngest sister, Mary, who had attended Albany Academy alongside Sarah, married Dr. Elias J. Blount in 1852. Like her brother, Blount was a physician, a state representative for his particular county, Pitt, at the time of their marriage, and a slaveholder. Martha Williams, another of Ben’s sisters, married William Williams of Duplin county, creating a marriage of wealth and privilege through his own extensive landholdings and number of enslaved laborers combined with Martha’s dowry, which no doubt contained additional property of land and slaves. After his untimely death Martha subsequently married her late sister, Fedora’s, widower, James Williams. Harriet, Martha’s daughter and another of Sarah’s classmate from Albany, married William Alexander Faison in 1848, moving to Sampson County, North Carolina, where they built a three storied mansion containing 16 rooms on the 2000-acre Faison plantation. Closer to home, Ben’s only surviving brother, James (1806–57) lived on a plantation adjoining Clifton Grove where he held 21 enslaved field hands in 1850.13 Far from the image portrayed by some historians of antebellum Southern planter families as detached and isolated family units with little contact with wider kin members, the Williams’ exercised influence and attained prestige through their expansive network of familial members, including both blood relations and in-laws.14

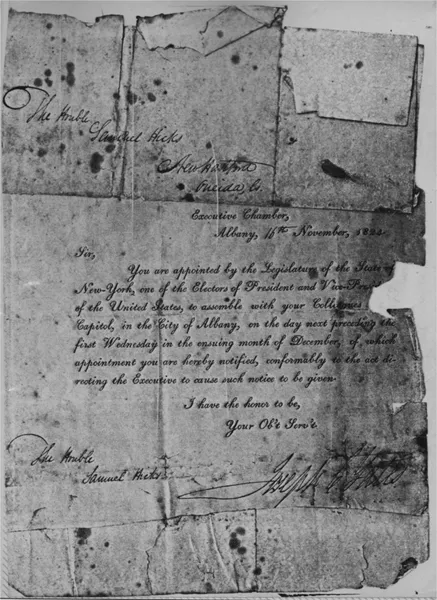

Sarah’s upbringing was of a similar background in terms of wealth and opportunities: for example, her father, Samuel, was listed in the 1870 census records with $4000 of real estate and $15,000 worth of personal estate to his name. No small amount for a retired farmer as he was listed in this particular census. His interests in the world of business and industry were clear however from his earlier years of employment, being named as manager of the New Hartford Cotton Manufacturing Company in 1821. Samuel subsequently retired from this position in 1837 to pursue business and real estate concerns, and presumably to devote more time to his landed interests.15 As one of New Hartford’s elite, Samuel was selected as one of the Presidential electors for John Quincy Adams in the contested election of 1824 (see Figure 1.1). As an old time Whig, who favored modernization and industrialization, the banks and federal spending on the infrastructure to boost business interests, Samuel was also a member of a political organization that considered themselves “the party of ‘property and talents,’” defined by their social elitism.16 In terms of privilege then, Sarah and Ben came from strikingly similar worlds. Yet, it was the very stark differences that Sarah found in practicing and performing those privileges between Oneida and Greene County which left her feeling as if she were a “stranger in a strange land” following her removal to North Carolina.

Figure 1.1 Samuel Hicks’ Letter of Appointment for Presidential Elector, c. 1824. Courtesy of Kathy Wright Fowler

Once the exclusive preserve of the colonial elite, what Richard Bushman aptly describes as a “diffusion of vernacular gentility” filtered downwards into the homes and lifestyles of the Northern middle-classes of America during the antebellum era. Such ideals were expressed physically, through the houses they acquired, or the furnishings that adorned these homes, and also more abstractly, through manners and morals. The Hicks family home at 18 Oxford Road, in the village of New Hartford, was finished in 1826, the year before Sarah’s birth (see Figure 1.2). The two-storey mansion, “a splendid example of Georgian architecture,” complete with the requisite white exterior and green shutters, which effectively “rose up and spoke out in brisk white,” was built with an acute attention to detail including the hand printed English wallpaper, made in 18-inch blocks, that decorated the hallway, and which their granddaughter reported in later years was “similar to the William Morris design … brought at … an importer[s] at … New York City.” Other notable features of the house included the glass in the fan light and blown glass side panels of the front door. The handrail running down the staircase, which was made from mahogany, an expensive and superior wood-type during this period, purchased from Gilmore and Benjamin, was complemented by the “beautiful engraved glass lantern in the hall.” The double parlor at the end of the hallway served the purpose of a dining area and two closets containing blue and gilt china adorned each room.17

Figure 1.2 Hicks’ Family Home, 18 Oxford Road, New Hartford, c. 1826. Courtesy of New Hartford Historical Society

Professional men such as Samuel Hicks devoted considerable energies (and no small amount of the family income) toward fashioning the home to demonstrate the Hicks’ achievements and wealth. The Hicks family residence was meticulous in both design and detail, evidently serving the purpose of presenting Samuel Hicks and his family to the community as respectable members of Oneida County’s elite.18 Indeed, an inventory provided by Sarah listing the items she had sent for from New Hartford to Clifton Grove included a tapestry carpet, a piano and stool, a corner stand, a collection of sofa chairs, two easy chairs, a sofa rocking chair and a marble top center table with a sola lamp and draping.19 Such high-end items suggested that the Hicks family were heavily invested in cultivating the “genteel home,” adorning 18 Oxford Road with furnishings that further enhanced their status specifically in the village and town of New Hartford, Oneida County, and in the State of New York more generally.

The Hicks’ home was located in a region of New York that witnessed a particularly fervent engagement with evangelical religion and subsequent reform movements during the first half of the nineteenth century. Oneida County was part of what one historian has termed the “Burned Over District,” where “in the decades before the civil war [the] region was set aflame with evangelical religion and reforming zeal.”20 As Northern fears concerning the unsettling influence of rapid industrialization, urbanization and immigration grew, the fear of social divisions gripped numbers of Americans from the bourgeoning middle-classes. In order to anchor the disquiet at the vast social, economic and political changes occurring in antebellum America many among the white, Anglo-Saxon cohort turned to religion “in numbers and intensity that have not been surpassed before or since.”21 The Protestant evangelical Great Awakenings of the mid-eighteenth and early nineteenth century in America witnessed particular styles of conversion and shifts in theological thought that laid emphasis on self-reflection and scrutiny, humble piety, the importance of spreading the word of God through preaching and attacks on clerical privileges. The most fundamental shift in Protestant theological doctrine however occurred in the Second Great Awakening and concerned the move away from Calvinist ideas of election by an unforgiving God to an emphasis on human agency in order to initiate salvation.22

The stress on reforming souls through the spreading of the gospel led to a renewed urgency concerning the salvation of American society. Laying the responsibility for one’s own and the nation’s deliverance onto individuals, evangelical thinking laid the groundwork for numerous reform groups involved in working toward a correction of the nation’s sins. Although, as Lori Ginzberg points out, “not all converts in antebellum revivals became reformers” there was a profound emotional and ideologically relationship between social reform movements of early to mid-nineteenth century America and the Protestant evangelical revivals of the same period: “Protestant reformers profo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Reading Letters, Telling Stories and Writing History

- 1 “Everything Here is So Different”: Changing Cultural Landscapes

- 2 An Identity in Transit: From “True Woman” to “Southern Lady”

- 3 Familial Relations: North and South

- 4 Articulating a Southern Self: Georgia, Sunnyside and the Confederacy

- 5 Reconstructing Southern Womanhood

- Postscript

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index