- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In many countries, the number of people working beyond pension age is increasing. This volume investigates this trend in seven different countries, examining the contexts of this development and the consequences of the shifting relationship between work and retirement.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Paid Work Beyond Pension Age by Simone Scherger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Labour Economics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction: Paid Work Beyond Pension Age – Causes, Contexts, Consequences

Simone Scherger

1.1 Paid work and retirement: A shifting relationship

The institution of retirement is a defining characteristic of modern and contemporary welfare states. After a long period of decreasing effective and, in part, statutory pension ages in many Western countries (see, for example, Blossfeld et al. 2006), this trend has started to reverse in (Western) Europe since around 2000. Connected to this and against the background of demographic ageing, retirement and its relationship to work have become contested issues (again).

Over and above these shifts in the timing of the transition into retirement, the boundary itself between working life and retirement has become more blurred. Partial retirement or partial pensions before normal pension age, flexible transitions into retirement, volunteering and other activities during retirement and paid work1 beyond pension age, often whilst receiving an (old-age) pension, are the most important examples of these blurring boundaries. The interpretation of increasing post-retirement work varies widely: it can be seen as a deplorable exception from (the social right to) retirement, as a welcome flexibilization of the life course, as a ‘solution’ to problems connected with demographic ageing or as the result of a successful fight against age discrimination. One aim of this book is to achieve a more precise description and analysis of post-retirement work, in order to allow informed and well-based conclusions on the potential consequences of its growth.

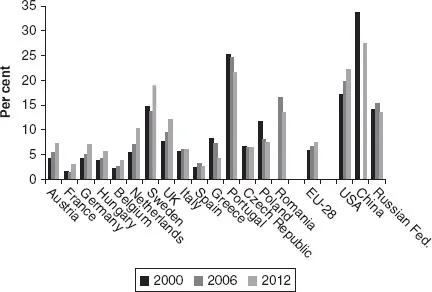

To illustrate the recent trends, Figure 1.1 shows the employment-to-population ratio among men aged 65 and older in the 15 most populous countries of the EU, the average of the EU-28 countries and the three other countries discussed in this book: the USA, China and the Russian Federation.

Figure 1.1 Employment-population ratio for men aged 65+ in selected European and other countries

Notes: Romania: data for 2000 unavailable; China: data for 2000 and 2010.

Source: OECD (2014) data.

Source: OECD (2014) data.

In Europe, the starting levels of employment of men aged 65 and older are low in 2000 (around five per cent or less), except for Sweden, Portugal and Poland and, to some extent, the UK and Greece. Until 2012, the ratio increases in most (North-)Western European countries, as well as across the EU-28 countries, whereas it tends to decrease or stay the same in (South-)Eastern and Southern Europe, where some countries have high starting levels of employment. While in the USA more and more older people are in employment, starting from an already high level of around 17 per cent in 2000, this does not apply to China and the Russian Federation which also have high employment ratios from the beginning. Trends for women (not shown) are, in many cases, roughly similar, but on a lower level. Although these shares still seem to be low in Northern and Western Europe, it has to be kept in mind that they cover all those aged 65 and over, with the rates for men aged 65 to 69 being much higher, for example around 25 per cent in the UK and in Sweden in 2012.

Regarding the employment wishes that people of main working age have for their retirement, according to recent Eurobarometer evidence a third of EU citizens (EU-27; European Commission/TNS Opinion & Social 2012: 74–6) say that they would like to continue working after they reach the age when they are entitled to a pension. The related percentages vary widely between EU countries, from 16 per cent (Slovenia) to 57 per cent (Denmark). Differentiating by age, the average share of those wishing to work beyond pension age is highest among those aged 55 and older (41 per cent).

Paid work after pension age, whether or not an old-age pension is received, is not a new phenomenon. Although public old-age pensions for state employees such as civil servants and soldiers were available from the 18th century onwards and early forms of occupational pensions were developed soon after in some industrial sectors or banking, the first more general public pension scheme was only introduced towards the end of the 19th century in Germany (Kohli 1987; Thane 2006). Such early public pension schemes only covered a small fraction of the population, and they were not aimed at completely substituting working incomes. They were only supposed to complement incomes from paid labour, which decline in old age and due to ill health. Pension recipients usually continued to work, be it in formal paid labour, often experiencing downward occupational mobility (Ransom and Sutch 1995), or in subsistence economy – or they were supported by their children, other relatives or poor relief. Their risk of being poor was high. In most Western welfare states, it was only sometime after the Second World War that retirement as a work-free and, consequently, distinct phase of life had become part of most people’s lives (Thane 2006), as payments from public and/or occupational pensions were high enough and covered a majority of the population. Retirement had become part of the ‘institutionalised life course’ (Kohli 1986), the normative ‘programme’ (Kohli 1986: 291) consisting of education, employment and retirement which people, in particular men, expected to pass through during their lives. This normative programme also served and still serves – to differing degrees in different countries – as point of reference for regulations in social policy.

The increase in work beyond pension age and/or despite receiving an old-age pension thus not only raises questions associated with this late employment itself, its patterns, drivers and consequences on different levels. It also challenges the fundamental meaning of old age, retirement and old-age-related policies and, in a wider sense, also the institutionalized life course. In comparison to related topics, such as employment just before pension age, the transition into retirement and volunteering in old age, work past pension age has been much less in the focus of research. While work after pension age has been studied for at least two decades in the USA, notably because rates of post-retirement work have been higher there for a longer time, and for at least a decade now in the UK for similar reasons, the subject has not or only very recently been investigated more broadly in other European countries (with some early exceptions, for example in Germany, see Kohli and Künemund 1996; Wachtler and Wagner 1997). Therefore, much of the research summarized in this introduction focuses on the USA and the UK. The studies presented in Chapters 4, 5, 6 and 7 of this book can be counted among the first to investigate working pensioners in these countries. The relative lack of research applies even more to a comparative perspective (with the exception of Eurofound 2012 and Alcover et al. 2014). This edited book aims at examining post-retirement work in a systematic and comparative way and at discussing some of the broader issues raised by old-age work. The following sections of this introduction give an overview of the negotiated themes and issues, existing research and the contributions to this book. Although this synopsis cannot be complete, in particular with regard to existing research, it sets the scene for what follows.

1.2 Post-retirement work: Definition, types and relationship to earlier career

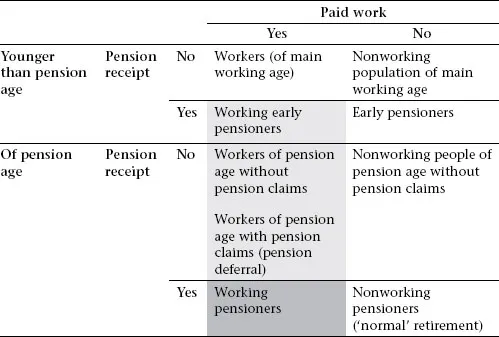

Retirement is the transition into as well as the life phase itself that marks the end of the working career. This life phase is characterized by the absence of paid work and usually implies receiving an old-age pension (or, in some cases of early retirement, a disability pension). ‘Work in retirement’ or ‘work beyond pension age’ thus mean combinations of working, receiving an old-age pension and having reached pension age which do not correspond to the institutionalized setup of this transition or life phase, that is, the expected and ‘normal’ combination of being of pension age, receiving a pension and not working. Consequently and in contrast to ‘normal’, nonworking pensioners, different subgroups of people working beyond pension age can be differentiated (see Table 1.1; also Scherger et al. 2012: 16–18).

Working pensioners in a strict sense combine pension receipt with paid employment, whereas those of pension age who are working and not receiving a pension either have deferred receiving their pension(s) or do not have any pension claims from their own employment record. Age further complicates the picture, as in many pension regimes certain old-age pensions can be drawn before statutory pension age, which is often combined with working, creating a category of pensioners working before (regular) pension age. The definition of ‘retirement’, and thus the differentiation of post-retirement work, is further complicated by the fact that pensioners can receive payments from several pension schemes, possibly starting at different ages – which is particularly relevant in multi-pillar pension systems.

Table 1.1 Combinations of age, work and pension receipt

Source: Own table (extended version of Scherger et al. 2012: 16).

Distinguishing different forms of post-retirement work might seem academic. However, with these different forms, the experience and the consequences of post-retirement work will vary, and their incidence will differ between countries depending on the institutional context such as pension systems and labour markets. Although in most countries, working pensioners (pre- or post-pension age) dominate the picture of those combining work and pension receipt in unusual ways, in some pension systems (such as in the UK), pension deferral is not uncommon, amongst others because it is rewarded by higher pension payments later (Crawford and Tetlow 2010).

Further possible differentiation of post-retirement work concerns the relationship of the post-retirement job to the one before reaching pension age or starting to receive a pension. Most importantly, this relates to the questions as to whether the employer, the employment status (dependent employment or self-employment, for example) and the occupation are the same as before retirement and whether people restart working after some time of economic inactivity or simply continue working, in an unchanged or changed working arrangement, for example with regard to hours worked. Depending on the dimensions studied, ‘stayers’ or ‘continuers’ can thus be distinguished from ‘movers’ and ‘recruits’ (Smeaton and McKay 2003; Lain 2012), with the latter sometimes experiencing downward occupational mobility (Lain 2011: 90). Some of the more complex terms used to denominate post-retirement work, such as ‘bridge employment’ (for example Alcover et al. 2014), also imply ideas on what role this work plays in relation to the main career or to old-age provision (see the title of Parry and Wilson 2014).

1.3 Characteristics of paid work after pension age

The huge variety of pathways into and forms of post-retirement work defy simplifying descriptions or conclusions and also entail difficulties in empirically investigating and comparing post-retirement work. Nonetheless, regarding its basic features and structural characteristics, there are many similarities across European and other Western countries. In most countries, the majority of those working past pension age do so part-time (Banks and Tetlow 2008; Eurofound 2012: 37; Scherger et al. 2012). Although the occupations that are pursued cover a large spectrum, some are over- or under-represented in comparison to the employment structure of workers of main working age. The most clearly over-represented group in many countries are the self-employed or freelancers, often without or with only few employees (Hayward et al. 1994; Eurofound 2012: 39; Brenke 2013). While these might also include people who start self-employment late and in the prospect of retirement, or who give up dependent employment and continue their old occupation as a freelancer, there are indications that most of them were already self-employed before pension age. Furthermore, qualitative anecdotal as well as (potentially unreliable) quantitative evidence suggests that the share of post-retirement work that is done off the books is considerable (Eurofound 2012: 42).

Regarding sectors, jobs in manufacturing seem to be clearly under-represented in many countries, whereas professional jobs and sometimes those in retail and other services are more frequent among those of pension age (Smeaton and McKay 2003: 33; Eurofound 2012: 34). Information on the class profile of post-retirement jobs not only allows inferences about the pathways into and causes of late employment but is also associated with well-documented patterns of social stratification in retirement behaviour (Radl 2013) and a country’s employment structures and job opportunities for older people. Hokema and Lux (Chapter 3 in this book) find that post-retirement jobs are somewhat shifted towards the classes of unskilled manual and low-routine jobs in the UK in comparison to younger workers (see also Lain 2012), whereas this is not the case in Germany where self-employment gains more relative importance. These under-researched characteristics of work post pension age also help to characterize the structural role that working pensioners play on the labour market (see below).

1.4 Theoretical approaches to post-retirement work

Whether and how people work beyond pension age depends on a multiplicity of influences which can be structured in different ways. Hayward, Hardy and Liu (1994: 84; see also Hardy 1991) describe work after retirement as the result of two selection processes: first, the retirees’ self-selection into employment, and second, the selection of retirees wanting to work (or wanting to continue working) by the labour market. This distinction designates the two main areas of broader theoretical approaches to work beyond retirement: first, approaches focusing on the individual and his or her desire to work, and second, demand- or supply-based theories explaining what happens in the labour market. In the former area, often spelled out by scholars with a background in psychology, theories discussed include Atchley’s continuity theory of ageing (Atchley 1989) or role theory in general (see Kim and Feldman 2000; von Bonsdorff et al. 2009). Here, post-retirement work can be seen as an attempt to maintain a certain daily routine and work-related contacts, or to preserve the occupational role in order to avoid the disruption and the role loss connected to (full) retirement. Some of these non-material incentives of post-retirement work also resemble the drivers of voluntary activities, which also help people maintain social contacts and are a source of social appreciation (see, for example, Griffin and Hesketh 2008).

In the theoretical approaches connected to the labour market, general models of supply and demand are usefully supplemented by models of occupational stratification or segmentation of the labour market and dual queuing in labour queues and job queues (Lain 2012: 80 – in referring to Reskin and Roos 1990). Furthermore, it can be assumed that the factors which influence labour market participation in old age are the opposite of what facilitates or delays retirement transitions – a very well-studied field (for example Blossfeld et al. 2006; Radl 2013). The same factors that increase the probability of (early) retirement, such as bad health or unemployment, clearly pose barriers to post-retirement work, and comparisons can also be drawn with explanations of labour market participation in general and earlier in the life course. However, structural and institutional specificities of employment in old age shift and partly change the interplay of labour demand and supply with regard to people of pension age. The age boundary institutionalized in the pension system and in related legislation implies that people beyond pension age are not expected to work and ‘normally’ do not need to work because their default status is being a pensioner and their main sources of income are their pensions. This shifts the weight of many other factors in such a way that much stronger incentives together with other favourable conditions mu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on Contributors

- 1. Introduction: Paid Work Beyond Pension Age – Causes, Contexts, Consequences

- Part I: Country Cases

- Part II: Contexts

- Part III: Consequences

- Index