eBook - ePub

Hybrid Factories in Latin America

Japanese Management Transferred

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Hybrid Factories in Latin America

Japanese Management Transferred

About this book

Explores the Latin American economy and management through the study of Japanese companies in countries such as Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Based on detailed case studies, this volume offers a bird's eye view of foreign investments in Latin America.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

A Bird’s Eye View of Foreign Investments in Latin America

1

The Viewpoint of Research Analysis for Japanese-Affiliated Enterprises in Latin America

Katsuo Yamazaki

1 Latin American economy and business management

It is difficult to evaluate, as a whole, the economy of the Latin American countries, which range geographically from 32 degrees north to 55 degrees south. Latin America is generally said to be one of the most economically developed regions in the developing world, and its major countries obtained their political independence during the first half of the 19th century. Even though their economies were severely damaged by the world depression that began in 1929, they quickly bounced back from the mid-1930s onwards, achieving annual growth of 3.5 percent by 1950, far better than the 1.9 percent growth in the industrialized countries. The industrial architecture of Latin America underwent a significant change between 1950 and 1998. Agriculture, which accounted for 20 percent of GDP in 1950, had dropped to 10 percent by 1980, and this percentage remained unchanged thereafter. Manufacturing industry, on the other hand, rose from 30 percent of GDP in 1950 to 37 percent in 1980, and it was strongly influenced by the economic crisis that followed.

As a result of globalization, Latin American countries are undergoing drastic changes. The change since 2001, when we started our research, is especially noteworthy. For instance, Brazil, which has almost the same land area as the US mainland, developed its industries remarkably, and transformed itself into an oil-exporting country in 2006, through the success of Petrobras, its national oil company. Many Latin American countries, in the face of the negative effects of globalization, have been obliged to build a new development strategy. Among the negative impacts are the currency crises which these countries have had to deal with. The currency crisis in Mexico occurred at the end of 1994 and lasted until the beginning of 1995. The one that hit Brazil lasted from the 1980s until 1994 (the Real Plan), when the country was plagued by foreign liabilities and serious economic problems due to hyperinflation. The currency crisis in Argentina, which occurred at the same time we started our research, can be cited as another example. In this chapter we analyze how Japanese-affiliated enterprises adapted to deal with these difficulties.

One way to understand the Latin American economy would be to take an approach based on development economics. One such approach, which developed after the 1990s, is that of the new system school led by Popkin,1 which focuses on issues such as external economies, diminishing returns, technological progress, moral hazard and the policy management ability of the government. Another is the capabilities approach, in which Amartya Sen2 focuses on issues such as income distribution, freedom, human rights, military affairs, environment and gender. The two scholars differ in terms of their critical approach and logical framework; however, they coincide in the sense that both of them emphasize the importance of the micro approach.

Our study group has considered the Latin American economy from the perspective of the micro approach and the regional economic agreement. Despite twists and turns in internal policies, the Japanese-affiliated automobile parts assembly and parts production enterprises in Brazil and Argentina have already established their status in each country. The oil and gas industry in Venezuela and the first Japanese industrial sector in Chile – fisheries – have each contributed to the respective country through exports to Japan, although they have not adapted themselves to the import-substitution policy.

The main focus of development economics may lie at the level of national strategy; however, we prefer to use the micro approach to report how these countries pursued economic development. We also use the MERCOSUR (Mercado Común del Sur) Latin American countries and the ASEAN (Association of South East Asian Nations) countries as instances of regional economic agreement among developing countries. In addition, we analyze and compare the business management of Japanese-affiliated industries within the context of NAFTA (North American Free Trade Association) and the EU (European Union) as regional economic agreements among advanced countries.

2 Method of analyzing the management of Japanese-affiliated enterprises in Latin America

Latin America is the chief supplier of mineral and food resources to Japan, and Japan is dependent on the Latin American countries for its imports of silver (52 percent), copper ore (50 percent), iron ore (17 percent), molybdenum (68 percent) and soy beans (18 percent).

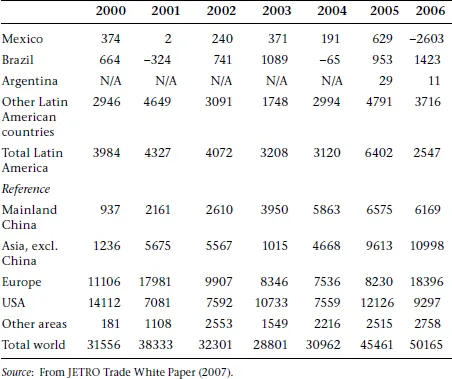

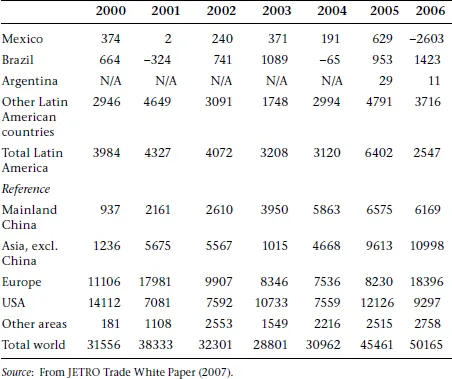

However, compared with the substantial increases in its investment in other parts of the world, Japan’s investment in Latin America has increased only gradually, as shown in Table 1.1. In Mexico, although investment had been on the rise until 2005 because of the positive effect of Mexico being a member of NAFTA, in 2006 it decreased by half to 1.773 billion dollars, with some enterprises transferring their site of production to China. (See Table 1.2.)

Table 1.1 Japan’s outstanding FDI amount (yearly net flow based on balance of payments), by country and region (US$ millions)

Table 1.2 Japan’s outstanding FDI amount (year end), by country and region (US$ millions)

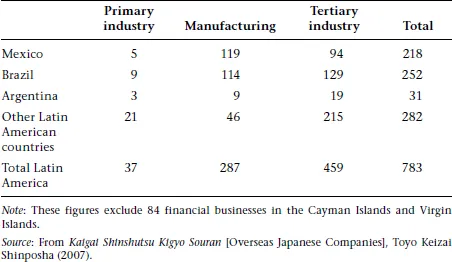

As we can see from Table 1.3, there are at least 783 Japanese-affiliated enterprises in Latin America. Of these, 287 belong to manufacturing and 459 belong to tertiary industries dealing with sales or service. In terms of the site of investment, more than 200 companies have invested in Mexico and more than 200 in Brazil, and these two countries account for about two-thirds of the whole investment in Latin America. (See Table 1.3.)

Among the Japanese-affiliated enterprises in Latin America, our research has covered 242 companies in Mexico, Brazil and Argentina. We are aware of practically no large-scale research having been done before in Japan on management and production systems in Latin America. We have visited 40 companies and based our evaluation on 35 factories. We have visited the Japanese-affiliated four-wheel and two-wheel auto assembly and parts enterprises twice during the course of our research. Here we use the hybrid theory for analysis. This theory has been developed, through JMNESG’s observation and follow-up surveys of several industries, including automobiles, electronics and electrical machinery, as a method of studying the overseas transfer and development of the Japanese production system. We have published several research reports based on these surveys.

Table 1.3 Japanese companies in Latin America, by industry

Our theory has been constructed within a framework in which we analyzed the enterprises’ special features, such as competitive superiority, and local factors, such as localization, considering what kind of superiority the overseas factories of Japanese enterprises have, and how that superiority could be maintained alongside the needs of localization. While many commonly accepted theories see production-related factors across borders and in different management-related contexts as the determinant of quality, one of the most important points of our theory is that we take into account the human factor in management and labor and the related production system and technology as the determinant of quality in our analysis so that we can study the tension between application and adaptation.

To put it concretely, Japanese enterprises try to apply the Japanese system to local factories in order to make the most of their competitiveness. However, it is also necessary for them to try to ‘adapt’ themselves, whether they like it or not, by changing their system to suit the conditions of the locale. Consequently, the management of the local factories usually ends up as a hybrid combination of application and adaptation.3 This makes it necessary to try to analyze how and in what respects they apply and adapt themselves, and also what kind of hybrid pattern of application and adaptation is formed.

According to this theory, we assume that one of the characteristics of the Japanese way of management is that extraordinarily high working efficiency and quality control are realized through the pragmatic systematization of human resources and physical assets. In other words, we study the structure that focuses on what is happening on the spot and the system of management and administration as the characteristic core of the Japanese production system. In addition, we understand the peculiarity of Japanese society and culture to be the condition required to sustain the international competitiveness (and problems) of the Japanese labor–management relationship and management system. We consider such dynamism to characterize the Japanese system, and we examine the degree of transfer of each constituent element and how it leads to actual performance.

There are 23 constituent elements, or items, summarized into six groups, with the home country model and host country model contraposed with each other. Each local factory of the Japanese enterprises covered by our research is evaluated on a scale from 1 to 5 to show where it ranks between these two models. That is, the degree of application for each item for the Japanese-affiliated factory is assessed with respect to the scale of the home country model (score 5) and the host country model (score 1). If it is in between, it is assigned a score of 3; if it is closer to the home country model, 4. (The degree of adaptation is judged conversely.) Visiting members of JMNESG base their scores on the actual state of the factories using the assessment criteria for application and adaptation. The final judgment is consensual, with all the members discussing the company reports. Although individual members’ evaluations rarely differ significantly, sometimes subtle differences arise which they discuss for hours, or even days, to decide the company’s final score on one item.

This five-point-scale assessment offers a solution to the problem of the lack of accuracy that typically arises with assessment using descriptive terms. It makes comparison and adjustment easier. It also makes it easier for us to understand the whole picture by showing it in tables and figures. This enabled us to open up a wide area of analysis, such as various comparisons and correlation analyses among the 23 items and six groups and the calculation of averages for districts and industries of interest.

Although the hybrid theory of application and adaptation was formed through the observation of Japanese-affiliated factories in the United States, it can be applied to factories in other parts of the world. For example, Great Britain established its initial post-Industrial Revolution capitalism and its production system as the extreme opposite of those of its host country for American capitalism, which makes it possible for us to suppose that the British model would be close to the American model. (Even so, interestingly, what we found was that it was more like the East Asian model, close to the Japanese model, which is thought to show the change in British economic society.) However, when we evaluate Japanese enterprises in less industrialized regions, it is hard to say by what criteria we should decide on the degree of adaptation because there exists no definite functioning system there. Further detailed investigation could deduce the logical system, but it is too complicated to assume different criteria for each of the three countries in Latin America. In consideration of this difficulty we measured how deeply the Japanese way was rooted ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Part I A Birds Eye View of Foreign Investments in Latin America

- Part II Analytical Methodology of Our Research Mainly in Mexico, Brazil and Argentina

- Part III Case Analyses of the Strategies of Automotive Assembling Enterprises in Latin America

- Part IV Case Analyses of the Strategies of Electronics Enterprises in Latin America

- Part V Conclusion: Characteristic Patterns of Hybrid Factories and of Strategies in Latin America

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Hybrid Factories in Latin America by Katsuo Yamazaki,Tetsuo Abo,JuhnWooseok Juhn, J. Wooseok in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Commerce & Industrie automobile. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.