eBook - ePub

Governance, Performance, and Capacity Stress

The Chronic Case of Prison Crowding

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Public policy systems often sustain chronic capacity stress (CCS) meaning they neither excel nor fail in what they do, but do both in ways that are somehow manageable and acceptable. This book is about one archetypal case of CCS – crowding in the British prison system – and how we need a more integrated theoretical understanding of its complexity.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Governance, Performance, and Capacity Stress by S. Bastow in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Civil Rights in Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Traditional Explanations of Capacity Stress and Their Limitations

Take a snapshot of any public-policy system at a particular moment in time, and you will see a picture of equilibrium between the demands made upon that system by governments and society, and all the things that the system does (and does not do) to somehow meet those demands. Continually evolving values and expectations are balanced against resources, capabilities, and efforts of actors involved, all of which sustains an equilibrium that allows the system, in one way or another, to fulfil its purpose, do its job, add value to society – in short, perform.

Clearly, however, a snapshot of the system is insufficient to understand the dynamics which determine equilibria over time. The actors that constitute the system are continually in motion and, through their values, cultures, relationships, strategies, choices, and actions, they determine the dynamics of continually evolving equilibria. Characteristics of public-policy systems can be seen as outcomes of all this, properties of these equilibria and the dynamics which are contained within. This book is about one particular characteristic described as chronic capacity stress (CCS). It is examined through the lens of what seems like a classic and archetypal illustration – the familiar issue of prison crowding. Through this I ask some key questions:

•What is the nature of CCS?

•How and why does it sustain?

•And how can we develop ways to alleviate it?

For many core state services, prisons included, the systems that provide them may be seen as too important to be allowed to fail completely. Whereas failure in the private sector often, although by no means always, can lead to firms going out of business, core public-sector systems of the kind which are vital to modern society often seem to go on and on. It is inconceivable that a prison system, for example, would be allowed to fold or go bust (though abolitionists may be in favour). A consequence is that these systems tend to incorporate any imbalance or shortfall (between things society demands of them and their capacity to supply those things) into their equilibria. If demands are too high, then actors find ways of doing the best they can to cope and make the system (or at least their bit of the system) work. If resources or capabilities are too low, then actors can find ways of recalibrating expectations accordingly. This recalibration may be entirely strategic and instrumental. It may on the other hand be a genuine response to the need to find ways of rationalizing why a system is having to under-perform in the face of seemingly impossible constraints.

It is interesting therefore that political science and public policy literature over the years has tended to focus on the extremes of public-sector performance, either failure or excellence.1 Yet surprisingly little has been written about these positions in between, the tendency for public-policy systems to find ways of coping, getting by, managing without necessarily completely failing nor completely excelling in what they do. In the vignette in the opening pages of this book we have seen how a public-policy system can incorporate elements of success and failure simultaneously, and not only that, for these elements to be aggravating and compensating, linked and related to each other in often complex ways.

There are perhaps notable exceptions to this general blind spot. Rittel and Webber (1973) outlined the concept of ‘wicked’ public-policy problems, the kind which are intractable, complex, and never seem to get solved. Hogwood and Peters (1985) characterized ‘chronic’ problems as the kind which tend to ‘go on and on, and never appear to be cured’ (p. 10), and after long enough ‘become a fact of life rather than a problem’ (p. 11). Whether wicked or chronic, these problems are the kind that tend to get coped with, absorbed, and normalized. They may build up into acute problems every so often, or they may stay incubated in the system for long periods of time. They can behave in complex ways as both cause and symptom of dysfunction, and hence can seldom be reduced to simple causal factors. They may also get reified and given life of their own, and used to justify or excuse why characteristics of systems are as they are. Chronic problems in large policy systems, much like in humans in fact, tend therefore to be multi-faceted, and in need of holistic, all-round, and balanced diagnoses or interventions.

How then does public policy and political science literature help us to understand the dynamics of crowding and CCS? How do existing theories help us to shed light on why a large public-policy system may be able to sustain a situation of capacity stress over the long term? And how do existing theories help to capture the complexities and the multi-dimensionality of this as a chronic condition?

In this opening chapter, I turn to three well-established groups of theory for insights – rational choice theory, cultural theory, and system theory. Each in their own way offer insights into the dynamics of the problem. But independently they do not seem sufficient to capture the entirety of the chronic condition. As David Easton (1965) has pointed out:

No one way of conceptualizing any major area of human behaviour will do full justice to all its variety and complexity. Each type of theoretical orientation brings to the surface a different set of problems, provides unique insights and emphases, and thereby makes it possible for alternative and even competing theories to be equally and simultaneously useful, although often for quite different purposes. (p. 23)

As the analysis in the book will show, these three approaches should not be seen as potential competing theories vying to be the best and only explanation of CCS. Rather they must be seen as necessarily complementary approaches, interrelated and dynamic. We cannot and should not reject them, but merely entertain the idea that in order to understand CCS in its entirety, they must be broken down and redeployed in a more integrative way.

1.1 Capacity stress in a managerialist era

Ideas relating to stress on the state and public sector have long permeated political science and public administration. From the late 1970s, political scientists drew attention to problems of ‘ungovernability’ and ‘overload’ on the UK state, arising from a combination of unchecked growth in the size of the public sector and an expansion of the functions that government should be expected to fulfil (King, 1975; Rose, 1979, 1980; Birch, 1984). Political scientists pointed out that such expansion and growth had in effect reduced the capacity of government to deal with problems effectively, and this encouraged a sense of pessimism about what big government had become and how it needed to slim down and shape up. Capacity stress, in this context, was linked to perceptions of excessive weight and expectation, a demand side that had become too large for supply.

Whereas critics had complained about overload and excessive demand during the 1970s and early 1980s, waves of managerialist change from then on took perceptions of capacity stress to the other extreme. New Right doctrines began to gain dominance at the heart of the UK state, and underpinned ‘new public management’ (NPM) reforms throughout the 1980s and 1990s. These reforms focused more directly on efficiency and effectiveness of government and the public sector (Jenkins, 2008), inculcation of private sector management principles into the public sector, and the integration of private sector markets and competition into traditional monopolistic state forms of delivery. Christensen and Lægraid (2002) describe this as ‘one-dimensional economic-normative dominance’ (p. 301), in which ‘reform ideas are imbued with a common vision of a new orthodoxy with strong market and management orientation’ (p. 303).

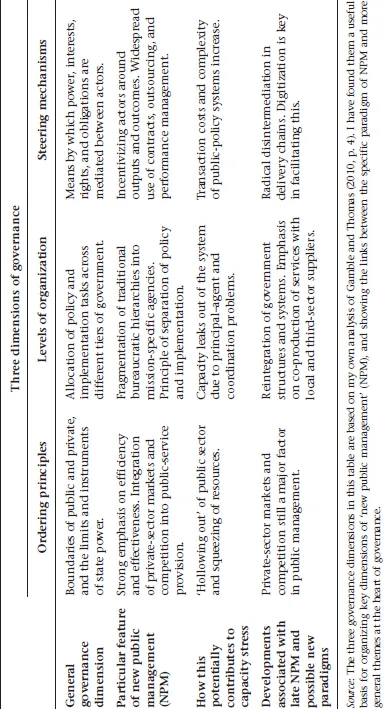

In many ways, NPM changes were a direct response and antidote to the kinds of problems associated with overload and ungovernability. Critics began to interpret the problem as one of supply-side stress, a ‘hollowing out’ (Rhodes, 1994, 1996; Foster and Plowden, 1996), and squeezing of resources and capacity within. Waves of privatization and outsourcing impacted on the public sector, and transferred generic administrative functions into private-sector management (Margetts, 1999; Walsh, 1995). Renewed emphasis on values of efficiency and effectiveness encouraged the need to think about maximizing impact from available resources and capacity, and systematic tightening or squeezing of resources over time (Chapman, 1982). Running a form of constructive under-supply of capacity provided a way of ‘sweating’ public-sector assets, ‘keeping its feet to the fire’, and heavy emphasis on performance targets and measurement sought to underpin ‘value of money’ in what the state and public services were providing. Table 1.1 summarizes key aspects of NPM change and links them to possible sources of capacity stress.

Clearly, however, such characterization of change from one extreme to the other seems far too simplistic. Critics have pointed out, for example, much of the pessimism associated with ideas of overload and ungovernability did not take into account the inherent resilience of the systems involved (Birch, 1984). As Goetz (2008) argues, the ‘gloomy scenarios of ungovernability [ ... ] have not materialized’ (p. 273). Likewise we may have seen signs of ‘hollowing out’ and ongoing financial stress to the public sector from contracting and outsourcing throughout the 1980s and 1990s, but this has not translated pound-for-pound into large-scale reductions in the cost or size of the core public sector, or in striking improvements in productivity (Dunleavy and Carrera, 2013). The state has proven resilient in lots of different ways. So we are faced, on the one hand, with conceptual models or paradigms of public-management change and, on the other, a more complex and mixed picture of actual change through time. This inherent ambivalence has not been lost on critics. Focus in the last decade has turned to the ‘paradoxes’ of managerialism and modernization (Maor, 1999; Hood and Peters, 2004; Margetts et al., 2010), and these insights have highlighted the limitations of the paradigm in how much it can tell us about the way in which large and complex public-policy systems work in real life.

Table 1.1 Key features of new public management (NPM) and how they relate to capacity stress

The rise and maturation of NPM will be a major theme of this book. In many ways, the prison system has been an archetypal adopter of NPM change, and it has also shown countervailing and indeed paradoxical dynamics in its relationship with system capacity and performance. As we will see, CCS appears to incorporate these dynamics simultaneously, on the one hand, squeezing and hollowing out (i.e. under-supply) and, on the other, aspects of overload and excessive expectation (i.e. over-demand). Similarly, as we will see, there is much about NPM that has helped the prison system to cope and indeed improve. But there is also much about it that has constrained and shaped the system in ways that have required it to cope in the first place.

Paradigms such as NPM provide useful tools with which to boil down complexity into manageable concepts, as well as help to explore the causal dynamics between them. The problem is, however, that once we begin to dig down into cases in more empirical detail, and understand these dynamics, it becomes apparent that these paradigms will only take us so far. In her stylish analysis of the problems facing the UK prison system, for example, Lacey (2008) uses ‘varieties of capitalism’ paradigms to argue that the political economic structures of liberal market economies, notably the UK and the US, create specific incentives for politicians and governments to allow prison populations to increase, while at the same time, deprioritize rehabilitative goals of prison and under-invest in non-custodial alternatives. It is a good example of how paradigmatic tools can be applied as explanatory or independent variables of change, and the neatness of the argument has much to recommend it. Nevertheless, as we will see throughout this book, to generalize about the dynamics of stress at a comparative-system level runs the risk that we normalize important forces within a system that seem to run counter to the predictions generated by the paradigm itself.

It seems necessary therefore to move away from specific paradigms, and formulate the theoretical schema for understanding CCS around the more general concept of ‘governance’. We can of course understand and interpret NPM in terms of governance, as Table 1.1 does. Governance can be seen as a more general set of concepts, whereas NPM can be seen as a specific paradigmatic variation of these concepts. There are of course potentially interesting links and commonalities between the two that are worth mentioning. For example, a key feature of NPM has been a disaggregation and fragmentation of what we might call traditional hierarchical bureaucracies, as well as the introduction of new types of actors into the policy process, not least the private sector. Inherent in governance literatures also has been a sense that public-policy environments and the institutions that give them shape have somehow become more complex and variegated. The need to control this more fragmented universe has encouraged the governance metaphor of ‘steering rather than rowing’ to describe the strategic challenge facing governments in a governance era (Peters and Savoie, 2000; Pierre and Peters, 2005). In this sense, the rise of governance can be seen as a response or antidote to the pathologies of NPM.

It is an interesting paradox, however, that some of the key assumptions and prescriptions of governance as an antidote to NPM indeed share many of the same principles of NPM itself. For a start, the concept of ‘steering’ implies a self-sustaining paradigm of public management, based closely on principles of markets in which economic actors respond to structured incentives that have been instrumentally designed. As Dunsire explains in Holistic Governance (1990), the challenge for governments under such principles becomes one of finding ways to intervene sufficiently to keep this self-sustaining logic of incentives and sanctions working towards desired outcomes. As his book title suggests, this must be a holistic enterprise, one in which policy makers are able to keep the whole system working towards desired outcomes. The basic point is that this discourse of institutional design and getting the incentive structures right is also at the heart of NPM doctrines. It is the idea that it is possible to intervene in all-encompassing ways, to influence all actors in the system, in the right way, all of the time. As we see later in this chapter, there are limitations to this doctrine of instrumental agency.

As a general approach to understanding the problem of CCS, however, it seems that governance must be the way forward. Its general mood value, prescriptive outlook, and broad applicability may make it difficult to define, as critics have argued (Rhodes, 1996), but this may also be one of its conceptual strengths in that it is not a pre-defined theory or paradigm, but a more loosely defined set of principles that can be used to understand the dynamics of whole systems and how they sustain particular characteristics. In this sense, governance gives us a certain conceptual looseness and flexibility with which to scope and build from first principles.

If our overarching approach to understanding crowding and CCS in this book is one of governance, then we must be clear about what the main components of a governance approach should be. Even proponents of governance over the years have acknowledged that the concept is still in need of greater specificity and more integrated understanding of how individuals that make up the systems interact with the institutional and cultural structures in which they operate. Peters (2010), for example, casts a critical eye over governance literature, and suggests that they ‘do not have any explicit mechanisms of integrating individuals and structures’ (p. 17). In many ways this book is an integrative project along these lines. It is an attempt to use a holistic governance-style approach to understand the dynamics of CCS and performance.

In the rest of this chapter, I examine what I consider to be three key aspects of such an approach – strategic actors, institutions and culture, and the dynamics of systems. Each has much to contribute to understanding of the overall problem of CCS. Yet, independently, each has limitations that only the others can mitigate.

1.2 Strategic actors, rational choices, and alignment problems

A good place to start in understanding why policy systems sustain CCS is with the individual actors who constitute those systems, and the way in which their choices and the decisions perpetuate the condition. From a rational-choice perspective, chronicity can be explained as a recurring outcome of the entirety of the decisions and actions taken by actors in the system over time. What is ‘rational’ in rational choice, however, is determined intrinsically by the structure of incentives that individual actors face (Coleman and Fararo, 1992; Scharpf, 1997; Besley, 2006). The underlying assum...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Traditional Explanations of Capacity Stress and Their Limitations

- 2 A More Holistic Governance-Style Approach

- 3 Performance and Capacity in a Managerialist Era

- 4 Measuring and Setting Capacity Standards

- 5 Senior Ministers and the Limits of Their Influence to Resolve the Capacity Problem

- 6 Top Officials and the Interface between Political and Operational

- 7 Governors, Staff, and Strategies of Local Adaptation

- 8 Privately Contracted Prisons: New Setting, Same Condition

- 9 Chronic Capacity Stress: A Complex Condition

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index