- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Exploring how restrictions on citizenship helped create conditions for political violence in Peru, this book recounts the hidden history of how local processes of citizen formation in an Andean town were persistently overruled, thereby perpetuating antagonism toward the state and political centralism in Peru.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Citizenship and Political Violence in Peru by F. Wilson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction

After the armed conflict in Peru, I returned to Tarma, a provincial capital in the Central Andes, to work on a research project about schoolteachers. I talked to teachers from wide-ranging backgrounds about their professional lives and, if the conversation allowed, their memories of the reform years of the 1970s and experiences during the internal war of the 1980s and early 1990s. One group I got to know well were the teachers taking the professionalization course at the Instituto Pedagógico Gustavo Allende Llavería, Tarma’s teacher training college. They had many years’ experience, and by attending classes during the long vacations, they could gain formal teaching qualifications. The teachers of the fifth year invited me to sit in on classes they organized themselves. In return, I offered to hold seminars on Tarma’s history, drawing on research I had done 20 years before in the local archives.

In 1996, in a crowded classroom, flanked by two Maoist class leaders, I presented an account of Adolfo Vienrich (1867–1908) and the radical workers’ movement in the town at the turn of the twentieth century. Interest was keen and debate lively. Everybody knew something about Vienrich—as scientist and pharmacist, teacher and newspaperman, writer on folklore and education. Some also identified him as the leader of the Radical Party who had confronted the propertied elite, and struggled to extend citizenship rights to the working classes and bring an end to indigenous labor service. He had then fallen foul of officialdom in the fight for municipal autonomy. But state centralization and authoritarianism were on the march. His suicide in 1908 coincided with a significant erosion of provincial powers of government and loss of political rights.

A week after my talk, a pamphlet, Confidencial, was on sale in kiosks all over town. A notice on an inner page named me as “a suspected subversive” under investigation by the police. Gathering up my documents, I set off in search of the chief of police. It took all afternoon to find him. He laughed off the allegation, assuring me that I should not take seriously rumors printed in that scurrilous rag. Later, I found out that the denunciation had been provoked by my seminar on Vienrich. The classroom informer had sold the story of Tarma’s radical past to the police and to a radio reporter who wrote for Confidencial. The memory of Vienrich was still alive and could still provoke reactions.

It was this incident that pressed me to think again about hidden histories of citizenship and dissent. Local radical tradition had a habit of resurfacing at particular political conjunctures; then the memory of transgressive local intellectuals acted as a guiding thread. Vienrich had become a kind of touchstone, portrayed as the innocuous folklorist in times of political repression, but as a radical campaigner for devolved power during political openings. I began to realize the significance of local radicalism in the context of Peru’s recent past. With this in mind, I went back to my old field notes and extracts I had copied from local archives and newspapers in the 1970s. I wanted to rethink citizenship, its formation and meanings for people in an Andean town and province, and how the suppression of successive waves of opposition might be linked to the recent political violence. This book is the result of that encounter between Tarma’s Maoists and el maestro Vienrich.

On the Lookout for the Path

This book tells a story of citizenship: what relations and rights it conjured up, how citizen formation was persistently thwarted by a centralizing state, and how claims to greater provincial autonomy fueled waves of radical opposition. We know the outcome of such processes in the late twentieth century. This was the internal war that convulsed Peru during which some 69,000 people lost their lives.1 Political violence revealed the depth of antagonism toward the state and its institutions. In this book, I shall not discuss the insurgency itself but inquire instead into the prior history seen from the vantage point of a provincial town and the region it administered. My contention is that to understand political violence we need to look at historical processes whereby local political institutions were stifled and ordinary people came to hold the belief that only through confrontation and revolutionary strategies could political change be brought about. This underlying preparedness is not captured when analysis focuses solely on a political party as protagonist and its top-down revolutionary project. In Peru, the spreading influence of the Communist Party of Peru, Shining Path, was because there were many, especially young people, in the Andean region on the lookout for a new radical path that would bring down the corrupt old order and lead them toward social justice and greater equality.

Before 1980, when the organized violence began, surprisingly little had been observed about the political crisis gathering force in Andean towns. Researchers had tended to look in other directions, to peasant society and to new communities springing up around Lima, the capital on the coast, as a result of migration. As Carlos Iván Degregori (2011: 41–42) points out, there was a dearth of case studies interrogating processes of change in small- and medium-sized Andean towns.2 Yet these urban societies had suffered severe dislocation brought about by the undermining of local institutions and a succession of projects of modernization begun by the central government but then abandoned. From the immensely valuable documentation of Peru’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, we have a panoramic view of the circumstances in which the university-based Shining Path party emerged and the devastation wrought by the Maoist revolutionaries and Peru’s armed forces. But little could be said about the historical trajectory of political dissent, or earlier instances of radical mobilization in towns of the region, or of how local people viewed their rights as citizens and relations with the state.

Where should we look for the roots of radical dissent; how far back in time do we need to go? Clearly from the time period covered by this book, I believe we should start with struggles for citizenship and for safeguarding provincial municipal autonomy in the late nineteenth century. There has been a tendency to portray Andean urban societies in stereotypical terms, as permanently dominated by conservative propertied elites and as redoubts of Hispanic culture. This book questions such a simplified view. My study focuses on Tarma in the Central Andes over a one hundred–year period, and I take up the following themes: How were citizenship and municipal government understood locally? What political reactions followed when local government was undermined by the centralizing state in the twentieth century? When and how did radical opposition movements emerge in the town and the province? And when, why, and how was political dissent transformed into dissidence?

The central argument I present is that conditions leading to the escalation of violence were created by the interaction of two long-term political processes. One was generated by the historical formation of the Peruvian state, in which advocates of state centralism prevailed over nation-builders who understood the potential of federalism, decentralization, and creation of political society from below. This was experienced in Tarma as the undermining of municipal autonomy, local electoral democracy, and active political rights. The second process was the evolution of political dissent that took the form of radical mobilizations, launched by opposition movements and parties from bases in provincial capitals. The overwhelming response of Peru’s presidents was to declare political opposition illegal and to put radical challengers “outside the law.” This had a double effect. On the one hand, it deepened a sense of exclusion from governing power. On the other, it led to a view that radicals were justified in organizing underground, in clandestinity, and that they had no choice but to hold fast to an uncompromising politics of confrontation. After introducing Tarma’s past landscapes and the archival sources used in the book, I shall situate my argument in relation to four current debates: liberal citizenship, electoral democracy, state formation at the margins, and political dissent.

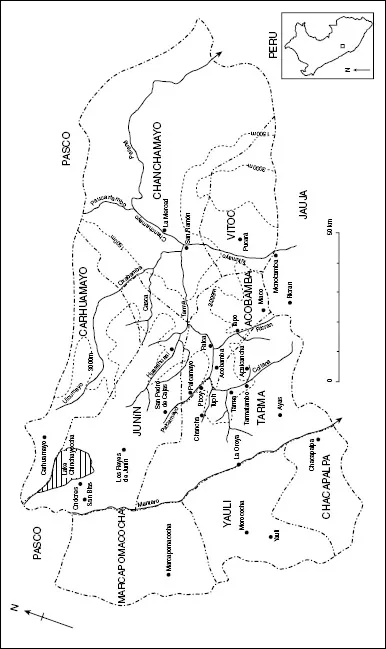

Landscapes of the Past

The province of Tarma lies on the eastern slopes of the Andean Cordillera, its capital some 130 miles by road due east of Lima and the Pacific coast. To reach Tarma, one has to climb up the arid mountains, pass the high-altitude mining zones of Morococha and Yauli (former districts of Tarma province), and then descend by a steep, winding road to temperate eastern valleys. (Map 1.1 shows Tarma province with the boundaries of 1900.) The town of Tarma lies at an altitude of 3,000 meters, on the road down to the tropical lowlands of the upper Amazon basin. The town is located at the upper end of a highly productive, irrigated, arable, valley heartland, where potato and maize lands meet. The indigenous-mestizo peasantry had held onto much of the land in the valley floors. In the highlands above, pastoral and potato-growing haciendas belonging to descendants of colonial propertied families formed a ring. To the north of Tarma province, we find the wealthy mining center of Cerro de Pasco and to the south the prosperous Mantaro valley and towns of Jauja, Concepción, and Huancayo.

Santa Anna de Pampas, later renamed Tarma, was probably founded in the 1570s, first as a doctrina (parish) and then as a reducción de indios (forced settlement of Indians) in a sparsely populated Inca province (Arellano 1988). The new town was built on swampy ground downhill from the Inca administrative center of Tarmatambo, a strategic hillside site on the Inca’s south-north “royal road.” In Tarma, Spanish colonists took over an ethnically diverse province, whose differences would be perpetuated in patterns of landholding and rights of belonging to the town. This went back to imperial expansions from the south, first of the Waris and then of the Incas who sent settlers to the region. From Tarmatambo, Inca overlords had realigned the provincial population, recognizing the land claims of eight pichqapachakas (large kin groups) and several ayllus (smaller kin groups). These kin groups held ancestral rights to particular portions of river valleys, irrigation systems, upland arable slopes, and highland pastures. The two largest groups, Collana and Callao, included many immigrants from Cusco sent to consolidate Inca rule, subdue the rebellious province, and control relations of exchange with the adjacent lowlands.

Map 1.1 Tarma province with boundaries of 1900.

On founding the new town of Santa Anna, the Spanish adapted the existing landholding structure and from it created the cercado (central district). Land claims of seven kin groups were now recognized, these becoming known collectively as the barrios (indigenous neighborhoods) of Tarma. Each barrio was allocated a sector of town where people were supposed to build houses and engage in the town’s ritual and religious life. Most people, however, continued to live in scattered settlements close to their lands. Relations between the seven barrios remained antagonistic, which, according to Arellano (1988), explains why there never developed a single indigenous community of Tarma. The Spanish town was built following the standard gridiron pattern composed of streets, squares, and residential blocks of uniform size. Urban space also consisted of a lattice of streets, squares, and open spaces, and incessant movement blurred the notional divide between town and country. It was in the town’s central square that contradictory meaning systems of Spanish elite, mestizo townspeople, and indigenous peasantry met. Bordering the square were the buildings proclaiming the town as a place of government: the church, office of the political authority, jail, and the office of the municipal authority. This was the obvious place to hold the market and religious congregations.

But a different history was also remembered, for the central square acted as the symbolic point of convergence of the founding ayllus and was a space of overlapping claims: of the seven barrios, upper and lower moieties, and the four cuarteles (urban districts).3 Surrounding the central square were the properties of the elite, enclosed by high walls, comprising houses, stores, and gardens. Up to the late colonial period, the houses of the kurakas (indigenous chiefs) were also to be found on the central square. Throughout the colonial period, people from the barrios as well as forasteros (newcomers) to the province settled in town where they exercised a craft or trade. They belonged to trade guilds and cofradías (lay religious brotherhoods) that the Church imposed on Andean society for the celebration of Christian festivals. Their modest houses and workshops were in the outer fringes of the town. Over time, the underlying diversity and barrio structure had been retained. As late as the 1860s, when the Italian naturalist and traveler Antonio Raimondi passed through Tarma, he was able to note down the names of urban streets, rural settlements, and small fundos (properties) that belonged to each barrio.4

The town grew in importance in the late colonial period when, unexpectedly, Tarma was named capital of an Intendency. More settlers arrived, taking over highland properties previously owned by the Church. Only in 1785, following pressure from the new property owners, was the Cabildo de Indios (Council of Indians) replaced by a Cabildo de Españoles (Council of Spaniards). At the start of the new republic, Tarma was named capital of one of four huge departments. But towns of the Central Andes competed for administrative advancement, and Tarma’s rivalry with the wealthy mining town of Cerro de Pasco was intense. In 1825, Tarma’s status was reduced to a mere district attached to the province of Cerro. A brief interlude as departmental capital followed in 1836, before Tarma was again outmaneuvered. Finally, in 1851, Tarma was made a province, belonging to the department of Junín whose capital was Cerro de Pasco.

The irrigated valleys downhill from Tarma had been densely populated in colonial times and produced maize, potatoes, alfalfa (as fodder for mules), vegetables, fruit, and dairy products. According to the population census of 1876, some 45,000 people lived in the province, and were concentrated in the valleys.5 In contrast, the highland portions of the province, that became its outer districts, were sparsely populated and dominated by huge hacienda properties, mining enterprises, and indigenous communities. The adjacent lowland region of the Chanchamayo, site of a rebellion in the late colonial period led by Juan Santos Atahualpa, had only been “re-colonized” in 1847. In the late nineteenth century, settlers flocked to the new colony. Most were of European extraction and they carved out large estates, which they planted with sugarcane and coffee. The province’s population was estimated to have risen to some 96,000 by the time of the 1940 census, with Tarma’s central district accounting for 20 percent of the total (Peru, Dirección Nacional de Estadística 1940). Small haciendas clustered in the uplands of Tarma district, accounting for 13 percent of the district population. Elsewhere, haciendas were dominant in the district of Tapo bordering Jauja province (accounting for 30 percent of the population) and Huasahuasi (16 percent of the population), and above all in the Chanchamayo lowlands where half the population lived.

While some aspects of Tarma’s history can be seen to reflect tendencies taking place elsewhere in the Andes, the province cannot be taken as representative. First, Tarma lay within easy reach of Lima and the port of Callao. Relations with the coast were relatively intense, and the province attracted a steady stream of newcomers eager to find new livelihoods in the resource-rich Andean region. Second, a wide cross section of the province’s population was able to benefit from income-earning opportunities opening up in the province’s highland and lowland margins. Following investment from the United States, the mining sector expanded in Tarma’s western highlands from the early twentieth century, and with it the demand for labor, pack animals, food, and other local products. To the east, in the Chanchamayo, aguardiente (cane alcohol) and coffee production was pushing out the agricultural frontier and depended on plentiful supplies of seasonal labor, pack animals, and foodstuffs from the Andean highlands. Directing my choice of case study was therefore not typicality but the existence of local archives and newspapers in the town from which to reconstruct a local history.

Provincial capitals can be visualized as concentrations of social, economic, and political networks, as center points of skeins of relations extending over space. These relations shift in scale, scope, and importance over time. In the following chapters, as the themes and time periods change, so too do the scale and the spatial relationships under discussion. My aim in each chapter is to tell a composite story by assembling archival and documentary material and also by letting witnesses have their say, whether through written text or recorded speech. The early chapters build on unique archival material relating to Tarma’s municipal authority. During my first fieldwork visit in the mid-1970s, I was introduced to this body of public documents which I refer to as the Tarma Municipal Archive (TMA). Included were some 40 folio-size, leather-bound volumes containing copies of the letters sent by mayors and their deputies. A further 20 ledgers contained the minutes of Provincial Cou...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Tables and Map

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 Introduction

- Chapter 2 The Provincial Council in Action: 1870–1914

- Chapter 3 Local Democracy and the Radical Challenge: 1870–1914

- Chapter 4 Adolfo Vienrich, Tarma’s Radical Intellectual: 1867–1908

- Chapter 5 The Politics of Folklore: 1900–1930

- Chapter 6 Indigenismo and the Second Radical Wave: 1910–1930

- Chapter 7 The Promise of APRA: 1930–1950

- Chapter 8 Teachers Defy the State: 1950–1980

- Chapter 9 Citizenship in Retrospect

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index