- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book is a timely study in light of the resurgence of resource nationalism that is currently occurring in several resource-rich, developing countries. It moves away from the traditional explanations for the disappointing economic performance of resource-rich, developing countries, notably those advanced by key researchers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Managing FDI for Development in Resource-Rich States by L. Barclay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Strategy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Importance of Institutional Efficiency to Resource-Driven, FDI-Facilitated Development

Introduction

The last three decades have witnessed a resurgence of FDI into the primary sector (fuel, ores and minerals) of some resource-rich developing countries. This surge in resource-seeking FDI has been triggered by privatisation schemes implemented in the context of structural adjustment programmes; favourable price movements in some commodities, for example, oil; growing demand from rapidly industrialising countries such as China and India and technological developments (UNCTAD 2005). The statistics are illuminating; for example, during the period 1989–1991, FDI inflows into the primary sector of developing countries totalled US$602 million. However, a decade later, these inflows increased by more than 300 per cent; during the years 2001–2003, FDI inflows into the primary sector of developing countries soared to US$1,855 million, which was a little more than 75 per cent of the value of FDI entering into the primary sector globally (UNCTAD 2007).

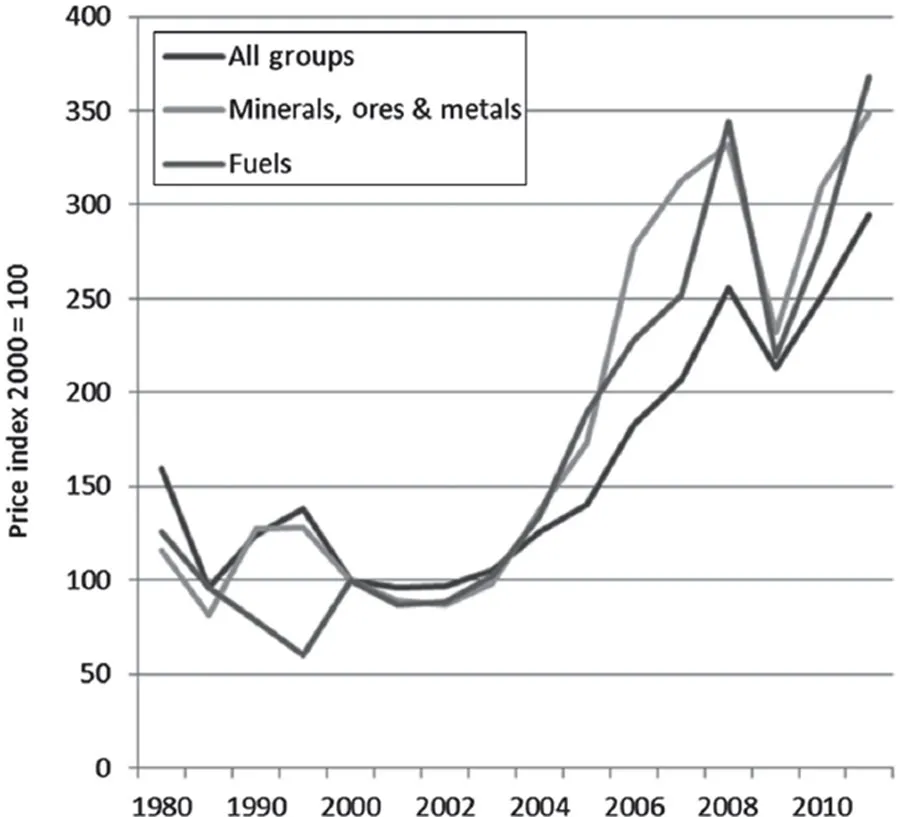

It is noteworthy that these FDI inflows have been accompanied by high commodity prices. After decades of low prices, the phenomenal growth of emerging market economies has fuelled price increases (see Figure 1.1). Global prices in non-agricultural commodities began increasing especially after 2002. This increase in non-agricultural commodity prices was briefly interrupted by the financial crisis of 2008 while the pre-2008 upturn, the 2008 to 2009 downturn and the post-2011 upturn were compounded by the actions of speculative investors (Kaplinsky 2011). Interestingly enough, these price increases are likely to persist. The economic ascendancy of the emerging market economies, notably China and India, along with the resource-intensive stages of their current development could result in a long-running acceleration of commodity–demand growth that would translate into high commodity prices (UNCTAD 2007; Collier 2011).

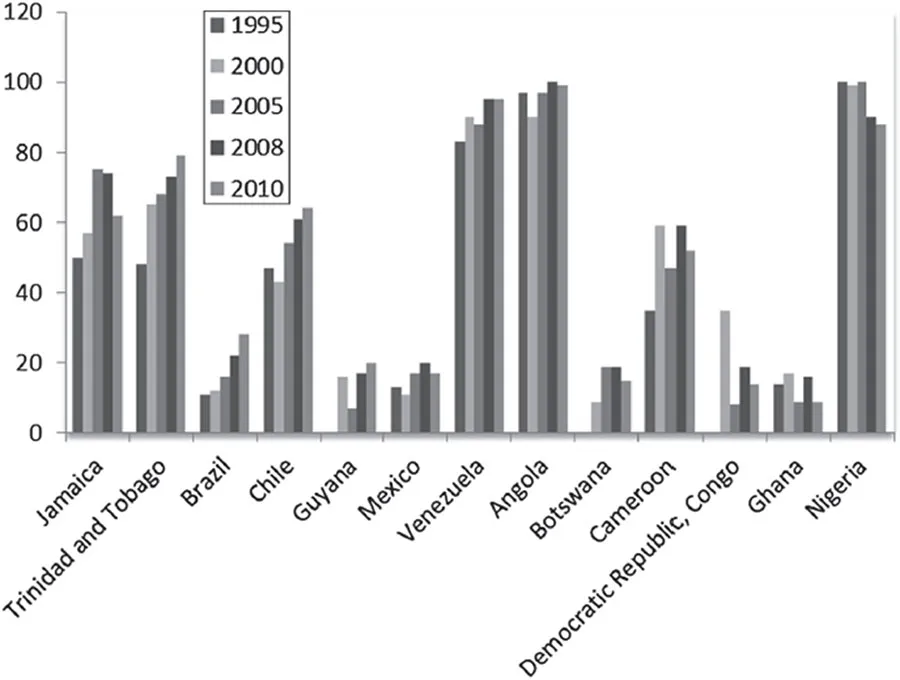

Not surprisingly, the resource-rich developing countries are becoming increasingly dependent on these renewed FDI inflows. As Figure 1.2 illustrates, over the period 1995–2010, the primary sector played a critical role in the economies of some developing countries: in notable cases such as Venezuela, Nigeria, Jamaica, and Trinidad and Tobago, mineral and fuel exports contributed more than 50 per cent of the total merchandise exports.

The 1990s have also seen a dramatic change in the development strategies pursued by many developing countries. Encouraged by the multilateral lending agencies, policy makers in most developing countries, including resource-rich ones, have abandoned dirigiste policies. The government’s role in most resource-rich countries is currently relegated to policy making and regulation.1 It is the private sector which is now bestowed with the task of economic transformation. Given the dearth of local entrepreneurs in many of these economies, it is the foreign firm, the MNE, which is currently operating in the non-fuel resource sector.2 Indeed, governments in many resource-rich developing countries are actively implementing investment promotion policies to attract these investors (for example, Wålde 1991). Thus, the engine of growth in many resource-rich developing countries is currently being manned by the MNE. Hence, it could be argued that the sustained economic development of resource-rich developing countries now partially rests on the activities of the resource-seeking MNE. This thus begs the question as to the role that the resource-seeking MNE could and should play in the economic development of these countries.

Figure 1.1 Non-agricultural commodity annual price indices, 1980–2011

Source: http://unctadstat.unctad.org/ReportFolders/reportFolders.aspx

Figure 1.2 Fuel and mining exports as a percentage of total merchandise exports, selected developing countries, 1995–2010

Source: World Trade Organisation Statistics Database, http://sta.wto.org/home/WSDBHome.aspx?Lar

The resource-seeking multinational enterprise and economic development in resource-rich developing countries

The shifting focus from fiscal benefits to positive externalities

The resource-seeking MNE emerged in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. By the 1960s, these MNEs, which often used and abused power, dominated the international resource industry (for example, Barnet and Müller 1974). During this period, the activities of the MNEs stimulated the interests of many researchers, who argued that these firms had the power, the resources and the global reach to hinder the territorial-based objectives of national governments in both developed and developing countries (Barnet and Müller 1974).

Hence, not surprisingly, much of the early literature that examined the relationship between the resource-seeking MNEs and their host developing countries focused on issues such as the distribution of power, costs and benefits between the two parties (Penrose 1968; Girvan 1970, 1971a, 1971b; Mikesell 1971; Vernon 1971; McKern 1976; Radetzki 1977). This relationship was oftentimes perceived as being exploitative with several writers positing that the long history of the resource-seeking MNE’s operations in these economies had only resulted in their persistent underdevelopment (see, for example, Girvan 1970; Levitt and Best 1975). These academic concerns were reflected in the nature of the concession agreements that were concluded between the MNE and the resource-rich developing economies during the pre-1980 period. Most of these concession agreements tended to concentrate primarily on maximising the fiscal benefits from the MNE’s activities in the economy. Dissatisfaction with these concession agreements reached a peak in the 1960s and early 1970s, culminating in nationalisations and even expropriations (McKern 1993). While there has been a recent shift away from concession agreements that focus primarily on fiscal benefits to ones that attempt to capture both direct benefits and positive externalities of FDI, including improved technological skills, management and know-how, induced investment in other industries and the upgrading of the general skills of the workforce (McKern 1993), little attention has been paid recently in the literature to the role that the resource-seeking MNE currently plays in enhancing the development prospects of resource-rich developing countries.

The resource-seeking multinational enterprise and stunted economic development: academic explanations

Interestingly enough, with the exception of few countries, it appears that the characteristics of production in the resource sector of developing countries have generally remained unchanged for the past century. Many resource-rich developing countries are still engaged in low-technology activities such as resource extraction with very limited processing of the extracted minerals being conducted locally. Research conducted in the early 1970s attempted to advance explanations for this manner of production organisation. One such study is the seminal work of Vernon (1971), which claims that factors such as history, the scale of investment required, the complexity of technology and the importance of downstream markets played an important role in determining the production structures adopted by MNEs in the petroleum and hard minerals (copper and aluminium) industries in the early 1970s.

Another study adopted the innovative value chain approach to examine the factors determining the extent and form of the MNE’s involvement in the non-fuel primary industries of developing countries (Girvan 1987). This study identified the industry’s production and processing technology and its market characteristics as influencing the barriers to entry, investment opportunities and rates of return at different stages of activity in these industries. Girvan (1987) further posited that the economic and political environment of the home and host countries also influenced the extent and form of the MNE’s involvement in the non-fuel primary industries.

A more recent and compelling explanation, which is firmly couched in the twenty-first century, was advanced by de Ferranti et al. (2002) who recognise that at present global trade differs significantly from what had occurred in the earlier twentieth century. Indeed, as Gereffi (2005) notes, in the pre-1913 era, the world economy was characterised by shallow integration, which was primarily manifested through trade in goods and services between independent firms and through movements in portfolio capital. However, the world economy today is characterised by deep integration, organised mainly by the MNE. This integration not only is pervasive but also involves the cross-border value-adding activities that redefine the kind of production process that is normally undertaken within national borders.

Thus, de Ferranti et al. (2002) argue that in the present globalised world, the progressive lowering of transport costs has considerably reduced the prospects of the MNE fostering backward and forward linkages in the resource sector of developing countries.3 The decrease in transport costs has resulted in fragmented production structures that would have constituted a ‘vertical cluster’ historically (de Ferranti et al. 2002, p. 70). Researchers including Jones and Kierzhowski (1990), Jones (2000), Jones et al. (2005) and Golub et al. (2007) postulate that these fragmented production structures have resulted in the emergence of production blocks, which are connected in a vertically integrated process by service links. They further argue that as the scale of production increases, the MNE finds it profitable to outsource several of these production blocks to countries where factor prices or productivity levels are lower than the marginal costs of the fragments. The costs of transport, communication and coordination between these blocks are the costs of fragmentation, and it is these that are decreasingly dramatically overtime.

Hence, these researchers posit that at present the fragmented production structure in many metallurgical industries such as aluminium and steel has resulted in ores mined in developing countries being exported for manufacturing to developed countries, which have the technology, the capital and other factors needed to efficiently produce the final product. Moreover, most of the intermediate goods and services needed for the mining activities conducted in developing countries are generally sourced from abroad. Nevertheless, this study argues that sustained economic development of resource-rich developing countries rests on the resource-seeking MNE fostering greater backward and forward linkages in the resource sector of the host developing country.

Linkage creation and resource-rich countries

It is noteworthy that the concern expressed above is not new. Indeed, since the early twentieth century, theories have been advanced to explain the manner in which the successful development of linkages could result in the sustained economic development of resource-rich countries. One of the earliest theories is the Staple Trap theory, pioneered by Innis (1920, 1933) and Watkins (1963), which sought to explain the development of the manufacturing industry in Canada that had emerged mainly from linkages to the export-oriented fur and fish industries.

The Staple Trap theory argues that the production function for staple production is important because of the possibilities of developing secondary and tertiary industries around the export base through the external effects of inputs demanded, outputs supplied, consumer markets created and education provided for by the export industry. Hirschman (1977, 1981) extended Innis’ work by identifying three types of linkages. The first type of linkage is fiscal linkages, which are the rents which governments are able to obtain from the resource sector in the form of corporate taxes, royalties and income taxes from employees. This rent could be used to stimulate industrial development in new economic activities. The second type of linkage is consumption linkages, which is the demand for the output of other sectors arising from incomes generated in the resource sector. The final type of linkage is production linkages, both forward (the processing of resources) and backward (the production of inputs and intermediate goods and services for the resource sector). It is significant to note that Kaplinsky (2011) has identified a fourth type of linkage, which is termed horizontal linkages. Horizontal linkages arise when capabilities developed in the formation of backward and forward linkages in the resource sector serve the needs of other sectors.

The record of successful linkage creation has been mixed. The experience of the Nordic countries of Sweden and Finland are often cited as examples of successful linkage creation. These countries, which were among Europe’s poorest in mid-nineteenth century, emerged to become one of the world’s richest and most highly developed economies by the late twentieth century. Blomström and Kokko (2007) attribute their phenomenal economic performance to the linkages these countries created in their resource sector – timber and iron ore. The countries initially created backward linkages in their resource sector, developing and eventually exporting simple intermediate products to more advanced Western European countries. They subsequently upgraded the technological level of their raw material-based industries and were thus able to establish the foundations for a more diversified economic structure. Over time, these countries created horizontal linkages, using the capabilities developed in the resource sector to successfully diversify into new economic activities such as machinery, engineering products and transport equipment. Notwithstanding the credible performance of these Nordic countries, many countries have been challenged in their attempts to successfully develop linkages in their resource sector.

Indeed, Baldwin (1956) examining staples such as the cotton and sugar plantations in the southern United States during the nineteenth century found that these staples were not favourable to economic growth. These industries failed to generate backward and forward production linkages since most of the non-labour inputs were imported and further processing of the staple tended to be carried out overseas. The skewed distribution of incomes attendant to employment in the resource sector limited the emergence of a market for locally produced consumer goods. As a result, dynamic consumer markets were not created locally.

It is noteworthy that the present record for resource-rich developing countries is very similar to that of the cotton and sugar industries of the southern United States in the nineteenth century (see, for example, Reynolds 1965; Girvan 1970, 1971a; Roemer 1979; UNCTAD 2001, 2007). It is also significant to note that unlike the studies done on resource-rich developed countries that were discussed earlier, many of the studies undertaken on linkage creation in resource-rich developing countries explicitly explore the operations of the resource-seeking MNE, which has historically dominated the resource sector of these countries. One notable ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction: Resource-Seeking FDI: Birth, Decline and Resurgence

- 1 The Importance of Institutional Efficiency to Resource-Driven, FDI-Facilitated Development

- 2 Introducing the Resource-Rich Caribbean Countries

- 3 The Aluminium Value Chain

- 4 Upgrading in the Aluminium Value Chain and Resource-Driven, FDI-Facilitated Development

- 5 The Changing Fortunes of a Strategic Industry: The Bauxite Industry of Jamaica

- 6 Policy Fluctuations in the Resource Sector of a Small Developing Country: The Case of the Bauxite Industry of Guyana

- 7 Dependent Underdevelopment? The Aluminium MNEs and the Bauxite Industry of Suriname

- 8 Addendum: Embedded Autonomy and the Industrial Policy Process in the Twenty-First Century: Developing an Aluminium Industry in Trinidad and Tobago

- 9 Resource-Driven, FDI-Facilitated Development in CARICOM: Myth or Reality?

- 10 Conclusion

- Appendix

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index