eBook - ePub

The Growth of Biofuels in the 21st Century

Policy Drivers and Market Challenges

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book provides a timely and insightful analysis of the expansion of biofuels production and use in recent years. Drawing on interviews with key policy insiders, Ackrill and Kay show how biofuels policies have been motivated by concerns over climate change, energy security and rural development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Growth of Biofuels in the 21st Century by R. Ackrill,A. Kay in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Biofuels and Biofuels Policies – An Introduction

Introduction

In recent years, for a number of reasons, governments have been increasing their efforts considerably to promote the production and use of energy derived from renewable sources. Concerns have been raised, for example, over the dependence on fossil fuels, the utilisation of which has considerable climate and environmental impacts. Moreover, in the case of oil, this creates an economic dependency of the vast majority of countries globally which lack oil resources upon the limited number of countries which have those resources, with many of whom political relations, and thus trade, are seen to be unstable and unreliable. There is also a widely held economic concern with oil that we are seeing the depletion of finite reserves, with consequences also for the price of oil.1

Renewable energies offer the chance to alleviate all of these concerns, whether they are directed at power (electricity) generation, heating (and cooling/air conditioning) and (road) transport fuels. That said, it cannot be taken for granted that just because an energy source is renewable and aids a shift away from fossil-fuel dependence, it is in all ways superior to the fossil fuel replaced. This is particularly the case with biofuels, the dominant form of renewable energy used in the transport fuel mix. Indeed, an analysis of the unintended consequences and side effects of biofuels policies, production and use represents a major theme of this book.

Oil, as noted, has a number of problems associated with it. Yet whilst the global energy matrix has, in the 40 years since the first oil crisis of 1973/74, reduced its dependence on oil considerably, transport fuel remains almost 100 per cent oil-dependent.2 This goes some way to explaining the ‘biofuels frenzy’3 seen since the turn of the millennium – and also the relative lack of attention paid initially to the potential downsides of different types of biofuel. This is, however, only one dimension driving the biofuels frenzy. Later in this chapter, we explore this and the other key policy drivers more fully.

This book is written neither an apologia for biofuels, nor an assault on them. Our intention, in contrast to almost all of the growing number of books on this subject, is to remain neutral in this debate. Rather, we take as our starting point a saying that we heard repeatedly in Brazil: there is no such thing as good biofuels or bad biofuels; only biofuels done well and biofuels done badly. There is nothing intrinsically good or bad about using renewable fuel in the transport fleet. Rather, what matters in determining whether biofuels are done well or done badly is a range of complex factors, where different types of biofuel policy promote different biofuels, produced in many different ways, derived from many different types of feedstock, with their performance judged against multiple criteria.

Our central aims, by the end of the book, are to analyse criteria by which biofuels can be judged as having been done well or badly, examine the trajectory of biofuels-promoting policies and analyse the links between policies and the delivery (or not) of the features policy-makers desire of biofuels. In so doing, we wish to allow the reader to be betterinformed about the range of factors which need to be considered in order to make his or her own mind up about different types of biofuel and biofuel policy, the range of possible policies and policy outcomes that are possible, and the challenges policy-makers face when designing and reforming policies.

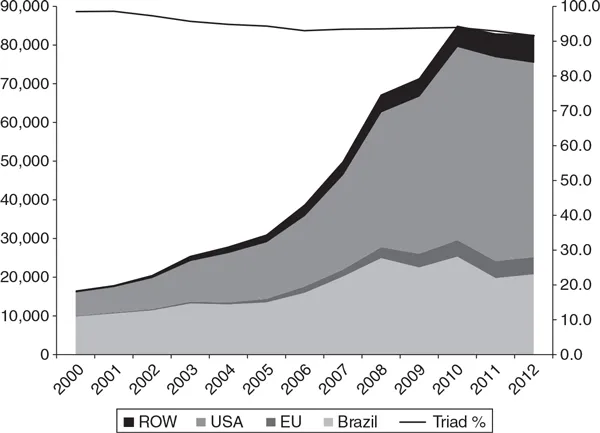

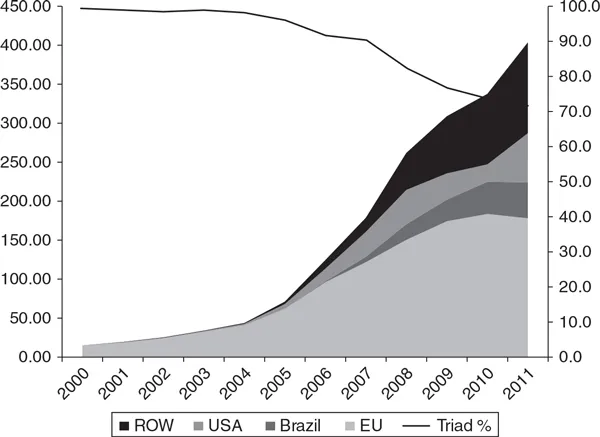

Our particular focus is on the following aspects: the policies of Brazil, the EU and US as the three dominant players in global biofuels markets (in 2012, Brazil, the EU and US produced over 90 per cent of global ethanol, and nearly 80 per cent of global biodiesel); ethanol and biodiesel as the two dominant forms of biofuel (very nearly 100 per cent of the market to date); and land transport as the consumer of biofuels. There are renewable transport fuels other than ethanol and biodiesel, being developed for aviation as well as road transport, but they are still essentially in the development stage, with almost no market penetration thus far. It is beyond the scope of this book to explore these, but the interested reader can follow this up via several of the references cited in this chapter.

What are biofuels?4

This is, primarily, a book about policies, policies used by governments around the world – but especially in our three focus countries – to promote the production and use of biofuels. In the EU and US, moreover, these policies are seeking to promote a large expansion in biofuels production and use, from a low base, in a relatively very short period of time. In this section, we begin with an introduction to biofuels themselves, recognising that whilst an elementary understanding of some of the technical aspects of biofuels is helpful to understanding the policy story we tell later, a detailed knowledge of the science of biofuels is not.5

At their most basic level, biofuels are fuels extracted or fermented from organic matter. Whilst there are several types of biofuel available for use as transport fuel, we focus on the two which dominate biofuels markets and the attention of policy-makers: ethanol and biodiesel. Moreover, each can be made from a range of inputs/feedstocks which can be classified in a number of ways, each emphasising different sets of characteristics. We look at the ethanol–biodiesel distinction next, followed by an analysis of how different biofuels (both ethanol and biodiesel) can be classified, based on the feedstocks from which they are derived.

Ethanol and biodiesel

Ethanol is derived from sugars, whilst biodiesel is derived from oils. Ethanol production is dominated by the US and Brazil which use, respectively, corn and sugarcane. With the former, sugars are extracted from the corn starch, whereas with sugarcane, there is a ‘direct’ route to the ethanol, via fermentation. One of the shortcomings of first generation ethanol derived from starch is that the starch itself represents a relatively small percentage of the total volume of biomass presented for processing. One potential benefit arising from the greater commercial development of second and third generation ethanol processes (discussed in the next subsection) could be to allow for the greater conversion of more of the total volume of biomass processed. This should mean, for example, a higher volume of biofuel produced per unit weight of biomass – which, depending on the feedstock, could also result in the delivery of a higher volume of biofuel per unit area of land used to grow the feedstock. Even so, this latter benefit would potentially be offset by the fact that some of these feedstocks would still involve the utilisation of land, and of a crop that can be used as food (we return to these issues in Chapter 9).

Ethanol is, typically, blended with petrol. Ethanol has a lower energy content per unit volume than petrol (roughly 70 per cent) but, with a higher octane level, it also improves the performance of the petrol. By improving the combustion of the fuel, it helps lower a range of emissions, such as carbon monoxide and sulphur oxide, as well as a variety of carcinogens. It may, however, lead to a slight elevation in the level of nitrogen oxide in the air. Engines have been developed which can run on very high ethanol blends, or even pure ethanol. These flex-fuel engines are utilised extensively in Brazil (see Chapter 2), but sales of flex-fuel vehicles (FFVs) are also growing in the US, especially the Midwest corn belt where E85, fuel blended to 85 per cent ethanol, is widely available. They are also utilised in parts of the EU, for example, Sweden. There remains no agreement over the level to which ethanol can be blended into petrol before engines need modification to avoid damage. Imported non-FFV vehicles in Brazil use domestic petrol which comes, typically, as a 25 per cent ethanol blend; whilst in the US, approval has only recently been given for E15 – and then only for newer vehicles. Interviews revealed that, in the EU, carmakers were reluctant to issue warranty cover even for E10.

Biodiesel production is slightly less concentrated globally than ethanol, but is still dominated by the EU, US and Brazil. The choice of (first generation) feedstocks is also more varied, and includes soybeans in the US; soybeans, castor and palm in Brazil; rapeseed6 in the EU; and oil palm in several tropical-belt countries. The two dominant forms of conversion of the feedstock are transesterification and hydrogenation, of which the former is the more widely utilised process (IEA Bioenergy, 2009: 34).7 According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO, 2008: 13), the performance gap between diesel and biodiesel is closer than between ethanol and petrol, with biodiesel having 88–95 per cent of the energy content of diesel. Moreover, biodiesel shares many of the engine functionality and emissions advantages of ethanol.

Despite these advantages, the production of biodiesel continues to lag behind ethanol. One likely reason for this is that, of the major biofuels players, diesel is an important fuel for cars and light vehicles only in the EU. Compared with ethanol, in both Brazil and the US biodiesel is a much smaller – but nonetheless growing – part of the biofuels scene, as Chapters 2 and 4 elaborate. Indeed, interviews in Brasilia with officials who are involved in Brazil’s biodiesel policy suggested that economic growth was expected to result in the demand for diesel doubling in ten years. This is because the country’s infrastructure means that the movement of people and goods is dominated by road transportation: buses, coaches and lorries.

Figures 1.1 and 1.2 show the production levels and shares of our three focus countries, respectively, for ethanol and biodiesel. As already indicated, the three countries dominate world ethanol production, with about 90 per cent of the world total. With biodiesel the dominance is not so great, but is still over 70 per cent.

Figure 1.1 Fuel ethanol production, million litres, 2000–2012, and triad share, per cent of world total

Source: International Sugar Organisation Ethanol Year Books, various years.

Biofuels – the generation game

The second distinction to explain is between first generation and advanced biofuels. The key distinguishing feature here is between feedstocks that can be used as food for humans and feedstocks that do not have such end uses. First generation biofuels are sometimes referred to as conventional biofuels. These are derived from feedstocks such as sugarcane, sugarbeet, corn, wheat, soybeans, palm oil, rapeseed, castor oil – all of which also have uses, either directly as food for humans or indirectly as animal feed. All of these feedstocks also require land for cultivation – the significance of which will be explored more fully below and in Chapter 9.

Advanced biofuels are, in turn, split further into higher generations. Second generation biofuels involve a range of inputs which do not compete directly with food uses. These include non-edible parts of food crops, for example, grain stover (stalks, leaves, husks, and so on), animal fats and the similarly waste elements of forestry. This category also includes non-food crops, such as certain types of grasses, which can be grown specifically for biofuels. That said, because this type of second generation feedstock requires land for its cultivation, some of the potential problems with first generation biofuels could still occur with second generation biofuels derived from such feedstocks. Another source of biodiesel is recycled cooking fats and oils. In this book we consider this to be a second generation biofuel because, as it is derived from waste products being recycled, its use for biodiesel no longer competes with its use as food.

Figure 1.2 Biodiesel production, thousand barrels per day, 2000–2011, and triad share, per cent of world total

Source: US Energy Information Agency.

There are, typically, two distinct definitions offered for third generation biofuels. One, specifically, describes biodiesel derived from algae. There is, however, a broader definition of third generation biofuels, an excellent summary of which is provided by Biopact8 (see also Liew et al., 2014). Second generation biofuel feedstocks involve bioconversion – the derivation of biofuels from the processing of a range of feedstocks. The Biopact definition identifies third generation biofuels as those derived from feedstocks which have been subject to ‘advancements made at source’.9 That is to say, there has been some adaptation made to the feedstock grown, prior to being harvested and converted into biofuel. Specifically, third generation biofuels are derived from feedstocks which have been designed as energy crops, with higher yields and improved bioconversion.

This latter point is very important, because it can lead to reduced production costs for biofuels, improved biofuel yields from feedstocks and so on. This development is, in part, a response to the fact that cellulosic biomass is a common feedstock type for second generation processes, but this has relatively high conversion costs because it is harder to break down than the sugars, oils and even the starch in first generation feedstocks (FAO, 2008: 18). The Biopact website cites evidence where plant-breeding efforts are leading to the development of feedstocks which already contain the enzymes required to break them down to produce fuels, making the process even easier and more cost-efficient.

Some studies also identify a fourth generation of biofuels. These are based on Utopian feedstocks which are capable of delivering a carbon-negative outcome (even the best renewable energy sources can only ever be, at most, carbon-neutral). There are two distinct stages of technological challenge with these biofuels. The first, on which scientists are beginning to deliver results, is to develop biomass crops capable of storing much more carbon than standard varieties. The Biopact website reports this is already being achieved with, for example, varieties of eucalyptus. The greater technological challenge comes at the stage of the conversion of these feedstocks into biofuels, where the carbon released is then captured and stored. Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technology is the key to delivering the carbon-negative outcome, and also offers benefits to the burning of fossil fuels, but successful commercial development remains elusive (see also Milne and Field, 2012).

In advance of detailed discussion in Chapter 4, we note here that US policy introduces a note of confusion into this standard classification of biofuels. It defines advanced biofuels in terms of the greenhouse gases (GHGs) emission reductions a particular biofuel delivers. Thus Brazilian sugarcane-based ethanol, as defined in the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA), is considered to be an advanced biofuel, based on its emissions reduction performance; notwithstanding the fact that, based on an agricultural feedstock, it conforms to the general understanding of a first generation biofuel.

A feature of first generation biofuels is that the production processes are well-known and long-established commercially. Given the multiplicity of feedstocks and technology pathways which can deliver biofuels, however, there is a commensurately large degree of variation in production efficiency, costs, energy outputs and emissions from first generation biofuels. The technologies required to bring advanced biofuels to market are, meanwhile, at various stages of development. In the US, in particular, the EISA, analysed in detail in Chapter 4, has helped bring small quantities of cellulosic ethanol to market. Meanwhile, more or less all of the biofuels produced in the UK, for example, are derived from waste products. These successes, however, remain on a relatively small scale at the time of writing, compared with the total volume of first generation biofuels delivered to market.

A key issue which arises from this dominance of first generation biofuels – and a theme running throughout this book – is the fact that first generation biofuels have the potential to produce a range of downsides, which policy-makers then have to try to manage. It is possible that the production of feedstocks for biofuels could affect the price of food products, affect the price of animal feeds, cause significant ecological and ecosystem damage, produce greater emissions of GHGs than the fossil fuels they are replacing, and trigger changes in th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables, Figures and Boxes

- Series Editor’s Preface

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- Part I

- Part II

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index