eBook - ePub

Ethnic Politics, Regime Support and Conflict in Central and Eastern Europe

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Ethnic Politics, Regime Support and Conflict in Central and Eastern Europe

About this book

Ethnicity and ethnic parties have often been portrayed as a threat to political stability. This book challenges the notion that the organization of politics in heterogeneous societies should overcome ethnicity. Rather, descriptive representation of ethnic groups has potential to increase regime support and reduce conflict.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Ethnic Politics, Regime Support and Conflict in Central and Eastern Europe by Julian Bernauer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & European Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Partisan-Descriptive Ethnic Minority Representation

Does the organization of politics along ethnic lines do more good or more harm? Scholars have long debated this seemingly simple question (Lijphart, 1977; Horowitz, 1985) without reaching a final answer. Case-wise evidence can support either side. While for instance power-sharing ‘consociational’ democracy and ‘politics of accommodation’ at the elite level (Lehmbruch, 1967; Lijphart, 1968, 1977; Steiner, 1974) have served some plural western European countries such as the Netherlands or Switzerland well, Belgium has recently experienced difficulties. In central and eastern Europe, the most extensive, externally enforced models of balancing power between ethnic groups in Bosnia and Herzegovina or Kosovo have not yielded the expected pacifying effects (Kasapovic, 2005; Taylor, 2005). In most of the ethnically diverse central and eastern European countries studied in this book, no such ‘consociational’ (or an alternative ‘centripetal’, see Horowitz, 1985) model of ethnic integration has been implemented, but the same question whether the inclusion of groups increases or decreases the stability of these systems remains of interest. While Turks in Bulgaria are well integrated in political, social, and economic terms, the same is not true for Roma communities in many countries, and the possible parliamentary representation of Russians in Estonia has neither taken off nor helped much.

This book analyses the empirical political situation of ethnic minority groups in central and eastern Europe, which implies a research focus involving two basic corner stones: the dominating electoral rule in the region is proportional representation, and (partly as a consequence) ethnic minority parties are widespread agents of group representation. Hence, a test of the performance of proportional representation via ethnic parties in terms of ethnic integration is provided. The results of the empirical analysis then partially answer the big question of the benign or malign character of descriptive representation regarding political stability.

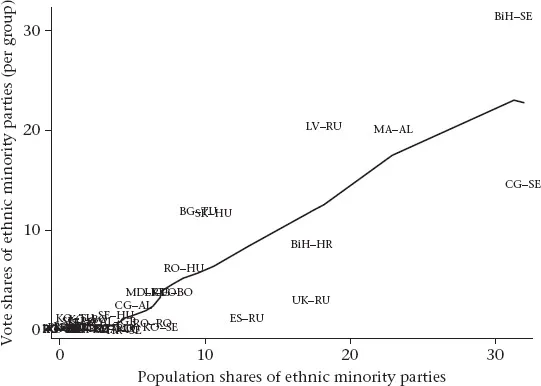

Central and eastern Europe is well suited for testing a ‘proportionalist’ vision of ethnic accommodation for a number of reasons. First of all, the region is highly ethnically diverse and has a history of ethnic conflict (Brubaker, 1996). Also, while the countries studied in this book either use proportional representation or mixed electoral systems (Shvetsova, 1999; Tiemann, 2006), electoral thresholds vary widely enough to test the influence of electoral rules on representation; there are many cases of ethnic minorities without their own ethnic parties or ethnic representation; and in some cases descriptive representation has been associated with stability and in others with conflict (Birnir, 2007, p. 3). Taking these observations together, the puzzling question is not only whether and when descriptive representation does more good or harm, but also why only some, and which, groups are exactly represented descriptively. This calls for contextual or group-level explanations, in particular as for example the vote shares obtained by ethnic minority parties are only partially explained by their population shares (see Figure 1.1). Hence, in addition to testing the consequences of descriptive representation for ethnic conflict, parts of the book are dedicated to the explanation of levels of ethnic-partisan representation.

To give a few stylized examples of the logic of the research in the book, consider the cases of the Turkish minority in Bulgaria, the Hungarian minority in Romania, and the Russian minorities in Estonia and Latvia. These ethnic minority groups show success and failure of partisan-descriptive representation respectively and the consequences for political stability. The Turkish minority in Bulgaria is mainly represented in a partisan-descriptive way by the ‘Movement for Rights and Freedom’ (MRF). The ethnic group faced discrimination and anti-Turkish activities such as campaigns for name changes from Turkish to Bulgarian or bans on the Turkish language and customs under Communist rule (Birnir, 2007, p. 131; Bugajski, 2002, p. 810; Warhola and Boteva, 2003). In the Post-Communist era, the party was remarkably successful in mobilizing its voters and gaining parliamentary as well as repeatedly executive representation despite a nominal ban on ethnic parties in Bulgaria (Birnir, 2007, pp. 130–6; Riedel, 2010, pp. 690, 700). The MRF even assumed the flexible and pivotal role of ‘king-maker’ not unlike the German liberal party (‘Freie Demokratische Partei’; Birnir, 2007, p. 130; Warhola and Boteva, 2003). Discounting some recent allegations of corruption (Riedel, 2010, p. 700), the case of the MRF representing its constituency in government (Birnir, 2007, p. 136) demonstrates the success of the ‘Bulgarian ethnic model’ of accommodation and participation as proclaimed by the MRF’s long-time leader Ahmed Doǧan (Riedel, 2010, p. 700). More generally stated, this shows the potential of ethnic politics to stabilize a political system and to be analysed through the theoretical lenses of general political science (Birnir, 2007), which is also at the centre of attention in this book. Similarly, the Hungarian ethnic minority party ‘Hungarian Democratic Forum’ (UDMR) in Romania demonstrates how inclusion in the executive can reduce antagonisms between ethnic groups (Birnir, 2007, pp. 119–30). Hungarians in Romania suffered from discrimination before and blame-shifting for the dire economic situation on behalf of the government shortly after the end of Communism, and claims of autonomy were the response at times, which have been moderated by access to power (Birnir, 2007, pp. 119–24). Notably, the two cases discussed also show that simple representation in parliament does not necessarily suffice to satisfy minority demands, unlike participation in the executive branch.

Figure 1.1 Relative group size and group-level vote share of ethnic parties for 39 ethnic minority groups

Note: Local regression line displayed. Discernible groups: BiH-SE = Serbs in Bosnia and Herzegovina, LV-RU = Russians in Latvia, MA-AL = Albanians in Macedonia, CG-SE = Serbs in Montenegro, BG-TU = Turks in Bulgaria, SK-HU = Hungarians in the Slovak Republic, BiH-HR = Croats in Bosnia and Herzegovina, RO-HU = Hungarians in Romania, UK-RU = Russians in Ukraine, CG-AL = Albanians in Montenegro, SE-HU = Hungarians in Serbia, ES-RU = Russians in Estonia, RO-RO = Roma in Romania, KO-SE = Serbs in Kosovo.

Other examples tell less successful stories for different reasons. Russians in Latvia and Estonia were members of the dominant group during Soviet times and, in particular in Latvia (Schmidt, 2010, pp. 128–30), have been struggling with issues of status, language and citizenship since the independence of the state. Although a good share of Russians in Latvia are non-citizens (Schmidt, 2010, p. 128), still around 20 per cent of those eligible to vote are ethnic Russians, while this number is slightly lower in the Estonian case. In the Latvin case, Russians are regularly represented in parliament (Schmidt, 2010, p. 156), for instance with the two ethnic parties ‘For Human Rights in a United Latvia’ (PCTVL) and ‘Harmony Centre’ (SC) in 2006 jointly obtaining a vote share very proportional to the population share. On the other hand, Russians in Estonia have failed to coordinate successfully into a strong ethnic party (Bugajski, 2002, p. 77; Lagerspetz and Maier, 2010, p. 90). While the group gained representation in parliament in 1995 with the ethnic electoral coalition ‘Our Home is Estonia’, it has more recently failed to clear the electoral hurdles, potentially also due to a vanishing salience of ethnic issues (Lagerspetz and Maier, 2010, p. 90). Hence, the partisan-descriptive representation even of large ethnic groups can fail for varying reasons, and in both cases the groups have not gained participation in the executive.

A few cases fit less neatly into the framework of this book, which pursues a systematic analysis of the determinants and consequences of partisan-descriptive representation. In many countries, Roma communities constitute a special ethnic minority without a true homeland (Fearon, 2003, p. 201) and are often subject to discrimination, suffer from socio-economic deprivation and generally ‘exist perennially on the margins of societies’ (Barany, 2002, p. 1). The political fractionalization of the groups (for instance in Hungary, see Bugajski, 2002, p. 365) and fundamental issues related to their socio-economic status such as the buying of votes1 suggest that the mechanisms of partisan-descriptive representation might well fail. In Bosnia and Herzegovina, deep ethnic divisions resulted from war and ‘ethnic cleansing’ in the 1990s, and the externally imposed, quasi-consociational (Kasapovic, 2005) constitution apparently does not suffice to overcome the tensions (Richter and Gavrić, 2010). In Ukraine, halfway into the civil war in 2014, antagonism in terms of ‘Ukrainian’ and ‘Russian’ ethnicity is part of the problem.2 But the conflict is surely far more complex, involving a lack of democratic consolidation including the party system and corruption issues (Bos, 2010, pp. 561, 565), economic aspects as well as the role of Russia as an external actor and the kin state of ‘ethnic’ Russians. Ukraine is also an example where ethnic identity is not clear-cut (Wydra, 2013) but partisan preferences of ethnic groups can be observed (Bernauer, 2013).

Moving beyond single cases, this book is dedicated to the systematic analysis of ethnic politics, representation and conflict, focusing on the descriptive representation of ethnic minorities in central and eastern Europe. It contributes by using state-of-the-art comparative political theory and methodology and shows that ethnic politics is less atypical than suggested at times, as general analytical lenses on voter behaviour, party competition, political attitudes and protest can be applied to the research field, and that there is some reason for cautious (and conditional) optimism that proportional, descriptive-partisan representation can contribute to the resolution of ethnic conflict. The research is guided by three strongly related research questions:

1.Which factors influence electoral entry and success of ethnic minority parties and the levels of ethnic groups’ partisan-descriptive representation in parliament?

2.Is there an effect of partisan-descriptive parliamentary representation on the regime support of ethnic minorities, and more precisely on individual levels of satisfaction with democracy?

3.Does partisan-descriptive representation in parliament and the executive impact on the protest behaviour of ethnic minority groups?

To be sure, the results of this study on central and eastern Europe might be extended to some, but not all, other regions and contexts. They mainly refer to settings of proportional representation, descriptive representation via ethnic parties, and emerging democracies. Other contexts, for example with different modes of representation, have their own logic (Bird et al., 2010; Ruedin, 2013). Where the main vehicles of ethnic representation are individual members of mainstream parties (Wüst, 2006) or ethno-federalism (Boix, 1999), proportional representation could potentially be substituted.

1.1 Ethnic identity and descriptive representation

This book studies the partisan-descriptive representation of ethnic minorities in central and eastern Europe.3 The region constitutes an ideal laboratory for the research questions at hand, given the shared history of its repeatedly reshuffled, ethnically heterogeneous countries. The last century saw two waves of political reconfiguration in central and eastern Europe (Brubaker, 1996, p. 55). The first was triggered by the decay of the Ottoman, Habsburg and Romanov empires in the early 20th century, which produced a number of new states. The second and even more consequential phase followed the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. Brubaker (1996, p. 55) states: ‘yet while nationalist tensions have not been resolved, they have been restructured.’ Former majorities turned into minorities, such as the Russians in the Baltic states (Brubaker, 1996, p. 56). Many other nationalities, such as Hungarians, Albanians, Serbs, Turks and Poles, were similarly dispersed. More recently, around 1990, the abrupt introduction of political pluralism in previously autocratic systems in a number of central and eastern European countries fuelled tensions in particular along an ethnic-nationalist dimension based on these historical circumstances (Bochsler, 2010a; Gurr, 1993, 2000; Fowkes, 2002; Evans and Whitefield, 1993). This political salience of ethnicity in central and eastern Europe gives practical relevance to the research presented. As a result of these historical developments, the size and number of ethnic minority groups varies widely, as do their levels of political activism, representation and conflict as well as the political-institutional context (see Appendix C for a list of ethnic groups and their electoral activity and success, and Appendix D for country-level variables).

While the issue of ethnicity has been revived in central and eastern European societies in the post-communist era (Fowkes, 2002), few but serious ethnically motivated civil wars manifested themselves in the 1990s. According to the Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP) Peace Research Institute Oslo (PRIO) Armed Conflict Database (Gleditsch et al., 2002; see also Cederman et al., 2009: 512), nine violent conflicts are identified in that decade. Most of them were a result of the disintegration of Yugoslavia and broke out during the pre-democratic transitional phase. Apart from these large-scale violent conflicts, ethnicity has played a considerable role in democratic politics (Birnir, 2007). In Birnir’s (2007) words, ethnicity has been used as an ‘attractor’ by political entrepreneurs to mobilize upon. Accordingly, in particular in new democracies, where political cleavages are still blurred, ethnic parties can at least initially stabilize the party system and hence the political regime (Birnir, 2007). The research presented follows these lines and inquires into (democratic) ethnic politics in central and eastern Europe, focusing on the explanation of partisan-descriptive representation and its non-violent consequences for satisfaction with democracy and the protest behaviour of ethnic groups.

To further clarify the scope of this analysis of democratic ethnic politics, the concepts of partisan-descriptive representation and ethnic identity are defined in the central and eastern European context. Virtually all modern states are sufficiently complex and large polities so that some variant of indirect democracy, and hence political representation, appears inevitable (Böckenförde, 1982; Dahl, 1989; Powell, 2004). Political representation is a multi-faceted concept. At least four meanings can be distinguished, including substantive (policy), descriptive, symbolic and procedural representation (Pitkin, 1967; Powell, 2004; Ruedin, 2013; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler, 2005). Descriptive representation is chosen as the focal analytical lens in this study. This is justified for both theoretical and methodological reasons. Theoretically (and empirically), descriptive representation is related to a series of other forms of representation, including policy representation and symbolic representation (see Banducci et al., 2004; Cunningham, 2002; Gay, 2002; Mansbridge, 1999; Pantoja and Segura, 2003; Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler, 2005, p. 411). Furthermore, in addition to being associated with policy and other consequence, descriptive representation is more or less visible and often clearly announced in party names and platforms so that it can be observed in a relatively direct way (Schwindt-Bayer and Mishler, 2005, p. 409; but see Moser, 2005).4 As parliamentary or semi-presidential systems as well as proportional electoral rules dominate (Tiemann, 2006), the formation of ethnic parties and hence partisan-descriptive rather than individual-descriptive representation is encouraged and builds the focus of the book (compare Birnir, 2007).

A widely cited definition of descriptive representation is given by Mansbridge (1999, p. 629): ‘In descriptive representation, representatives are in their own persons and lives in some sense typical of the larger class of persons whom they represent. Black legislators represent Black constituents, women legislators represent women constituents, and so on.’ The definition encompasses both visible characteristics and shared experiences. In simple analogy, it can be generalized to members of any ethnic group which are represented descriptively by members of their own group. The seminal book on the concept of representation by Pitkin (1967, p. 61) provides important qualifications: ‘the representative does not act for others; he “stands for” them, by virtue of correspondence or connection between them, a resemblance or reflection.’ As opposed to Mansbridge (1999), this definition already reflects Pitkin’s (1967, p. 91) critical view of descriptive representation.5 From Pitkin’s (1967, pp. 66, 91, 235) perspective, descriptive representation hence is a valid definition of representation, but only a partial and limited one. Most centrally Pitkin (1967, p. 89) diagnoses that ‘the best descriptive representative is not necessarily the best representative for activity or government’. This caution is widely acknowledged and can be most pointedly found in the assertion that ‘nobody would argue that morons should be represented by morons’ (Pennock, 1979, p. 314, cited in Mansbridge, 1999, p. 629; see also Pitkin, 1967, p. 89). Mansbridge (1999, p. 630) agrees that similarity is not action, and that the main criterion to judge descriptive representation is its ability to enhance substantive representation.6 Critics of ‘essentialism’ further argue that it can neither be guaranteed that all members of a given group primarily identify with the single characteristic defining descriptive representation nor that representatives emphasize the same values as the represented (Phillips, 1995; see also Mansbridge, 1999, p. 637). Hence, descriptive representation can be selective and imperfect (Pitkin, 1967, p. 87) or induce processe...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- 1 Partisan-Descriptive Ethnic Minority Representation

- 2 Partisan-Descriptive Ethnic Minority Representation as Politics

- 3 Explaining Partisan-Descriptive Ethnic Minority Representation

- 4 Partisan-Descriptive Ethnic Minority Representation and Regime Support

- 5 Partisan-Descriptive Ethnic Minority Representation and Conflict

- 6 Partisan-Descriptive Ethnic Minority Representation in Perspective

- Appendix A: Data Sources

- Appendix B: Election Sources and Minority Parties

- Appendix C: Ethnic Groups

- Appendix D: Descriptives for Chapter 3

- Appendix E: Descriptives for Chapter 4

- Appendix F: The Hierarchical Selection Model

- Appendix G: A Bayesian Multilevel Model

- Appendix H: Causal Considerations

- Appendix I: Votes into Seats

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index