eBook - ePub

The Circulation of European Knowledge: Niklas Luhmann in the Hispanic Americas

Niklas Luhmann in the Hispanic Americas

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Circulation of European Knowledge: Niklas Luhmann in the Hispanic Americas

Niklas Luhmann in the Hispanic Americas

About this book

This book studies the circulation of social knowledge by focusing on the reception of Niklas Luhmann's systems theory in Hispanic America. It shows that theories need active involvement from scholars in the receiving field in order to travel.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Circulation of European Knowledge: Niklas Luhmann in the Hispanic Americas by Kenneth A. Loparo,Leandro Rodriguez Medina in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Conceptualizing Knowledge Circulation: Methods and Theories

Abstract: Chapter 1 introduces a theoretical framework based on Baert’s (2012) idea of intellectual interventions, Science and Technology Studies’ (STS) approaches to boundary work (in particular Gieryn 1999; Lamont and Molnar 2002; Star and Griesemer 1989), and the geopolitics of knowledge circulation (Alatas 2003; Connell 2007; Mignolo 2000; Rodriguez Medina 2014). Instead of a typical reception study, mine is a case study of knowledge circulation, which means that I have not focused exclusively on those academics whose goal was to introduce Luhmann’s theory in the region but also the work of scholars who have used Luhmann’s theory in different ways, both on an intellectual and a practical level. This is supplemented by methodological considerations around life history and specifically about working life narrative.

Keywords: boundary work; intellectual intervention; subordinating object; working life narrative

Rodriguez Medina, Leandro. The Circulation of European Knowledge: Niklas Luhmann in the Hispanic Americas. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. doi: 10.1057/9781137430038.0004.

Niklas Luhmann was not particularly interested in making his theory travel abroad. Although he did not obstruct the projects through which scholars around the world tried to make his theory available to different audiences, he did not encourage them but warned about the complexity of his work and the difficulties of any translation. When a visiting scholar offered to publish the lectures he delivered at the end of his teaching career in Spanish, he doubted it made sense to try it. He was not sure how to transform an oral lecture into a readable, understandable book. The scholar recalls:

Then I let him know that it was not about transcribing (his lectures). “I’ll take notes, re-articulate (them), reconfigure (them) and then we publish them, following somewhat the logic (of his lectures).” So he said “Ok, do it”.1 (8.51; in translation)

Luhmann believed that his theory has European roots. In an interview conducted in Mexico City in 1992, he was asked, “A theory produced in Europe, like yours, would there be any problems if it was translated and applied to Latin America?” and he replied,

Certainly, I assume that this theoretical effort has a European context. I’ve just been to Melbourne for a conference about European rationality, in which the focus was second order observation. The observation of observation, instead of a direct description of the world as it actually is. It’s clear that this way of thinking is only possible as a consequence of European history, despite the rupture within this tradition. . . . This has to do with the assumption, which I accept, that modern world society was born in Europe. This does not mean that the European components develop as regional specificities in other places, but it does mean that certain aspects, especially the strong accentuation in the effectiveness of functional differentiation . . . only can be understood from the context of the European experience. (Torres Nafarrate and Zermeño 1992: 804; in translation)

Luhmann did not encourage the creation of international networks of scholars who would expand his theory. As one interviewee for this research responded, when questioned about his role as a sort of “master,”

He was never interested. . . . He did not gather disciples, we became his disciples by ourselves. In the end, his school, which still exists and is strong in Germany, was not “founded” by him. He never made any effort to generate groups of thought, to connect us with each other. He did not tell us “Write to him or work with her.” No. This was not his interest. (5.85; in translation)

He neither paid attention to specific spaces or places, because he saw his theoretical contribution as universal. In one of his most influential works, he argues that social systems “are not at all spatially limited, but have a completely different, namely purely internal form of boundary” (1997: 76, cited in Borch 2011: 137). For some, he “de-privileged . . . the spatial dimension” (Stichweh 1998: 343) and this seems to be one of the blind spots of his theory (Borch 2011; Filippov 2000). Even if his theoretical apparatus is assumed, the lack of interest in space can be seen as a weakness of his understanding of communication not as a theoretical concept but as an empirical, spatially grounded phenomenon (Borch 2011: 138).

Despite this, his theory has circulated worldwide and his influence in the social sciences is enormous (Poggi and Sciortino 2011). Moreover, there seems to be a “discovery” of his contribution to social theory in the United States and this foreshadows a new wave of interest in his theory. This chapter is a study of how his work, having overcome these obstacles, traveled to, and still circulates in Hispanic America.

1.1Work life narrative: a methodological approach

Many different methods and techniques can be used to study the circulation of knowledge, from quantitative examination of citation patterns (Schott 1993, 1998) to hermeneutic analysis of specific works (Burke 1995) and to institutional-biographical accounts of thinkers (Isaac 2012). Moreover, conscious reflection on the strengths and weaknesses of these macro- and micro-approaches has led some to propose meso-level comparisons between particular research projects (Shrum et al. 2007). The challenge is to connect the situated experiences of people involved in the process of circulation with the broad patterns, tendencies or structural factors that condition such experiences. For the purpose of this research, a work life narrative approach has been used because we think of the circulation of knowledge as a result of strategic decisions made by scholars (or knowledge workers) in order to structure their careers.2 In other words, knowledge circulation has to be analyzed vis-à-vis the intellectual and professional trajectories of those who actively participate in the process.

There are three assumptions that lie behind my use of life history and work life narrative. The first one is that narratives are important not only because they give us information about persons, things or events but also because they “lead to plans of action in the real world” (Goodson 2012: 8). Participants tell their stories in the way they do because that story has been (more or less) successful in giving meaning to their lives and consequently has become a guide, a plan, a project from which they judge their decisions and evaluate their future. Second, I assume, against some postmodern thought, that macro- or meso-narratives (such as the one necessary to understand any process/case of knowledge circulation) can be enacted and are the result of small narratives being permanently articulated. If something such as “structure” or “network” exists, it is because of the ongoing (re)configuration of people (with their bodies and narratives) and objects (with their semiotic and material dimensions intertwined). Third, life histories are more than life stories. The “life story that is told individualizes and personalizes. But beyond the life story, in the life history, the intention is to understand the patterns of social relations, interactions, and historical constructions in which the lives of women and men are embedded” (Goodson 2012: 6). In this regard, life history, as well as the work life narrative, functions as a link between the individual(s) and the collective(s) and also as a way of situating people, objects, and processes, avoiding the temptation of indemonstrable generalizations.

If a life-history approach is useful to contextualize the individual life story, the work life narrative will also be an appropriate tool to contextualize individual life stories about work. Although the idea of career as an institution seems to be at risk (Flores and Gray 2000), individuals—and academics in particular—still refer to it as a sort of organizing principle, or predetermined path, which has to be respected and followed or challenged and changed. In any case, “the issue people face today is not merely job insecurity, but more the loss of meaning that occurs when working life no longer has a discernible shape” (ibid.: 11). This uncertainty is what makes life stories more and more necessary: they provide meaning to a trajectory that is otherwise messy and insecure.

To study the reception and circulation of Luhmann’s theory in Hispanic America, I decided to inquire into the work life stories of those actors who play a decisive role in the process. In order to determine who these actors were, I relied on a pioneering text on the topic, Rodriguez Mansilla and Torres Nafarrate’s “La recepción del pensamiento de Niklas Luhmann en América Latina” (2006). At the same time, using databases such as Scielo and Redalyc, I obtained information about Latin American scholars who have published on Luhmann. Finally, through snowball sampling, other key informants were identified and contacted. The result of this search was a sample of 12 scholars (8 from Chile and 4 from Mexico) with whom I conducted in-depth interviews between 2012 and 2013.

Although the main source of information was the set of work life stories, secondary sources were fundamental to becoming familiar with the field of Chilean and Mexican social sciences, as well as the specific contributions of the scholars interviewed. Additionally, some of Luhmann’s works, when translated into Spanish, include important introductory studies written by leading scholars. These studies allowed me not only to become familiar with Luhmann’s biography and understand parts of his complex theory but also to know specificities of the links between Latin American scholars and Luhmann. These texts describe the reasons, obstacles, and goals of translating Luhmann’s books into Spanish in order to make them available to a broader audience. Along with the interviews, the introductory studies provided elements with which to identify strategies developed by scholars in the past four decades to position Luhmann’s work in the landscape of Hispanic American social sciences. However, before describing and critically evaluating these strategies I shall explain why Luhmann’s theory is relevant to studying the circulation of knowledge, and will justify my focus on social science in Chile and Mexico.

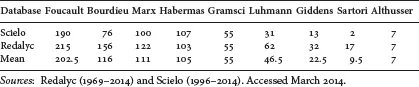

There are important reasons for choosing Luhmann’s work as a case study. The first is that Luhmann’s social theory is one of the most comprehensive attempts to develop a grand theory and probably the most ambitious since Parson’s sociology. As a grand theorist, Luhmann’s contribution lies in his scope of application, his multidimensional understanding of social processes, his influence on many disciplines, and his interest in new foundations for the social sciences, one linked to evolution theory, cybernetics, and communication. An indication of Luhmann’s relevance is his inclusion in a recent publication on “great minds” of 20th-century social science (Poggi and Sciortino 2011). As the authors point out, the book introduces theorists “who have made particularly significant, distinctive, and controversial, contributions to the development of modern social theory” (ibid.: i). Table 1.1 shows the relative importance of Luhmann in Latin America, by exploring how many articles have been devoted to analyzing (some parts of) the work of leading sociologists.3

TABLE 1.1 Articles devoted to leading sociologists in Latin American journals

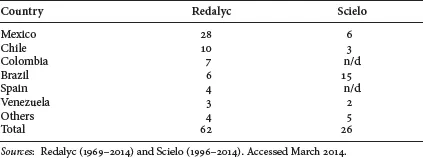

TABLE 1.2 Articles devoted to Luhmann’s work in Latin American journals, by country

In turn, Table 1.2 shows where the articles were published, pointing to the relevance of Mexico and Chile in the Spanish-speaking world, along with the important role played by Brazil.

The second reason is the tension between the scope of Luhmann’s theory and his contextualization of it as a “European endeavor.” Although general and abstract, his theory seems to have roots in an idea of rationality—as functional differentiation—that is Western and European. In an interview conducted with Luhmann in Mexico, Torres Nafarrate and Zermeño asked him whether his theory could be translated and applied to the Latin American context, and he replied that “in undeveloped regions these conditions [of differentiation] are not completely set up” (1992: 805; in translation). The third reason is that Luhmann’s work is complex and innovative to allow room for local social scientists to “interpret” it and, by so doing, their intermediary role in its reception deserves attention (Davis 1986).

The reception of Luhmann’s work in Hispanic America was possible because of a specific set of circumstances that prevailed in Chile and Mexico. The first translation into Spanish of Luhmann’s main work (Soziale Systeme. Grundriß einer allgemeinen Theorie), originally published in Germany in 1984, appeared in Mexico in 1991. The translation was undertaken by Silvia Pappe and Brunhilde Erker, under the supervision of Javier Torres Nafarrate, Professor of Sociology at Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico. The book was published by Universidad Iberoamericana, Mexico, and Alianza (a Spanish publishing house) and Luhmann visited Mexico when the book was launched as a strategy to make both himself and his work even more visible in the context of Mexican social sciences. In the Spanish second edition (1998), Nafarrate wrote a preface (1998: 17–26) in which he showed a deep understanding not only of Luhmann’s theory but also of the controversies that it had produced, particularly in the German context. However erudite it might be, the preface is, as he acknowledges, a first and basic approach to Luhmann’s contribution. Since then, Luhmann’s work has seen a presence in Mexican social scientific literature (Varela 1995; Galindo 1999; Torres Nafarrate 1999; Vallejos 2005) and a recent scholarly conference, held at Universidad Iberoamericana in 2007, was devoted to his work. In such a context, Luhmann was compared with Aristotle because of the depth of his theoretical contributions and with Marx, Durkheim, and Weber because of his relevance to modern social theory (UIA 2007; see also Zamorano-Farías 2008).

In Chile, Luhmann’s reception has also been broad. Perhaps one reason is that Luhmann took one of the main concepts of his social theory, Autopoiesis, from a Chilean biologist. Humberto Maturana—a Chilean scientist trained in London and at Harvard—has been a major theoretical influence through his studies of the capacity of systems of self-creation and reproduction, which Luhmann considers an essential feature of social systems. The second reason is that some Chilean social scientists were trained in Bielefeld, where Luhmann worked for several decades. Juan Miguel Chávez, Marcelo Arnold, Aldo Mascareño and Darío Rodríguez were some of the most relevant of Luhmann’s followers and responsible for his introduction to Chile (Rodriguez Mansilla and Torres Nafarrate 2006). Recent publications on Luhmann and the possible applications of his theory to different fields are the third reason for his wide reception in Chile. Farías and Ossandón (2006a) have presented an edited volume in which they analyze the influence of Luhmann on fields such as music, gastronomy, literature, education, science and technology studies, and sociology. The reception of this book in the context of Chilean social sciences seems to be an indication of the relevance not only of Luhmann but also of his disciples, and of system theory as a valid theoretical framework (Carballo 2009). The final reason for choosing Chile and Mexico is that Luhmann’s importance is such that international conferences have recently been held to evaluate his contributions (Rodriguez Mansilla 2008; UIA 2007).4 In February and March 2007, the Universidad Iberoamericana at Mexico City organized an international conference on Luhmann entitled “La Sociedad como Pasión” (Society as Passion) in which experts from Chile, Mexico, and Europe met to “celebrate the first complete translation [into Spanish] of Luhmann’s La Sociedad de la Sociedad, the most comprehensive systematic explanation of modern society in current sociology” (Torres Nafarrate and Rodríguez Mansilla 2011: 9; in translation). As a result of this meeting, Javier Torres Nafarrate and Darío Rodríguez Mansilla edited “Niklas Luhmann: la sociedad como pasión. Aportes a la teoría de la sociedad de Niklas Luhmann,” published by Universidad Iberoamericana Press in 2011. In October 2008, academics from Universidad de Chile, Universidad Católica de Chile, and Universidad Alberto Hurtado (a private, Jesuit University based in Santiago) organized and attended an international seminar on Luhmann, ten years after his death, at the Goethe Institute, Santiago de Chile. The conference was titled “The challenge to observe a complex society” and helped to consolidate the network of international scholars of the region whose work is connected to Luhmann’s.5

Along with the strong influence exerted by Luhmann, the social sciences in Chile and Mexico are interesting case studies because they are peripheral scient...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Introduction

- 1 Conceptualizing Knowledge Circulation: Methods and Theories

- 2 Bounding Luhmann: Different Strategies to Appropriate Foreign Knowledge

- 3 Luhmannization: Identity and Circulation

- 4 Comparing Knowledge Circulation: Euro-American Social Theories in Latin America

- Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index