eBook - ePub

Coffee Activism and the Politics of Fair Trade and Ethical Consumption in the Global North

Political Consumerism and Cultural Citizenship

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Coffee Activism and the Politics of Fair Trade and Ethical Consumption in the Global North

Political Consumerism and Cultural Citizenship

About this book

This book explores the politics borne of consumption through the case of coffee activism and ethical consumption. It analyses the agencies, structures, repertoires and technologies of promotion and participation in the politics of fair trade consumption through an exploration of the relationship between activism and consumption.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Coffee Activism and the Politics of Fair Trade and Ethical Consumption in the Global North by Eleftheria J. Lekakis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Civil Rights in Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Understanding Coffee Activism, Ethical Consumption and Political Consumerism

Coffee activism, market growth and fair trade consumption

The importance of coffee to the world economy cannot be overstated. It is one of the most valuable primary products in world trade, for many years second in value only to oil as a source of foreign exchange to producing countries. Its cultivation, processing, trading, transportation and marketing provide employment for hundreds of millions of people worldwide. Coffee is crucial to the economies and politics of many developing countries; for many of the world’s least developed countries (LDCs), exports of coffee account for more than 50 per cent of their foreign exchange earnings. (International Coffee Organization1) ‘Coffee activism’ is an umbrella term for the fair trade movement and actors beyond the official network.2 This single-issue type of activism includes a number of voices and agendas that range from the more directly political to those which are more consumer oriented. It is a polymorphous cause which involves the fair trade movement, as well as initiatives which are concerned with the promotion of ethical practice and conditions in the chain of global coffee trade. These include solidarity campaigns, cooperatives and alternative trade organisations (ATOs),3 as well as eco-labelling schemes4 and other certification labels.5 Coffee activism has undergone a variety of alterations in its growth since its inception as a social and trade justice movement, offering an alternative model for international trade, and has transformed into a mix of ‘campaigning traders’ and ‘trading campaigners’.6 It has also been adopted and adapted by corporate commercial enterprises that have entered its market, transforming it from niche to mainstream. Coffee activism seeks to balance trade injustice by setting and activating mechanisms which protect the ‘global South’ and raising awareness in the ‘global North’. In doing so, the movement encompasses a variety of principles on social and environmental justice issues. Fair trade is primarily concerned with the promotion of the motto and practice of a ‘fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work’, as well as an environmental, developmental and gender equality agenda.

Importantly, coffee activism is both a movement and a market. As such, it requires a thorough exploration of the politics of con-sumption; coffee activism constitutes one of the most sustained types of ethical consumption, or, in terms of political science, political consumerism. Participation in coffee activism includes a range of practices from single-consumer preference to fully committed engagement in protesting and lobbying, as well as the boycotting of unethical coffee trade. One might be involved in coffee activism through one’s church, by supporting their Sunday stall of Traidcraft goods, or through one’s local supermarket, by purchasing that brand of coffee with that blue and green design on a black background that is the Fairtrade Mark. One can also be more enthusiastically engaged by attending regular meetings at a borough campaigning group (a group concerned with bringing fair trade principles and accreditation to the local community) or maybe a march organised by the Trade Justice Movement (TJM) or a coffee morning during Fairtrade Fortnight.7 The fair trade movement has grown its roots in contemporary British society through a variety of organisations and means, and the majority of consumers across this country can now readily identify the Fairtrade Mark and are familiar with its basic connotations. Coffee activism has been gaining impetus as a powerful form of consumer politics. The phenomenon reflects the contemporary complexity of citizenship which touches upon different realms of our everyday lives and most appreciably that of consumption. This book outlines the ambivalent position of ethical fair trade consumption as an act of consumer citizenship. Rather than merely discussing consumer agency in the marketplace, I also reflect on civic agency in the political space. Consequently, the analysis focuses on the digital narratives and on/offline practice of the coffee activism movement and market in terms of mobilisation, cultural politics and political communication within and beyond the marketplace.

The politics of consumption can illuminate people’s engagement with broader political issues, which are always embedded in particular histories. The journey of coffee is characterised by long and diverse processes of historical transformation. The discovery and journey of the drink coffee began in its Ethiopian birthplace, from where it moved to the Middle East and the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth century; coffee only arrived in Europe a century later and since then its popularisation was only a matter of time. From the banning of the product in Mecca in 1511 to its introduction to Europe by the Ottomans through diplomacy and war (Wild, 2004), several social, political and cultural issues arose as a result of its development as a commodity. Along with commodities such as bananas and sugar, coffee has known a bleak history of trade rooted in the heritage of colonialism.8 The heritage of the unjust coffee trade history stretches to contemporary times. As a product in the global market, coffee involves networks of intermediaries between producers and consumers. Its politics are interwoven not just with consumption and consumer culture, but also with the contentious politics of trade justice. The interplay between these traditions has resulted in coffee becoming a powerful object for political contention.

Low points of the recent dark history of the coffee commodity include the 1989 collapse of the International Coffee Agreement and the fall of the ‘C’ price9 ten years later. A political economy of the coffee trade exposes the consequences of these market crises which have severely impinged on the developing world:

Just as farming families may be heavily dependent on coffee for their income, so are many nations. A handful of African countries rely on coffee for more than half of their foreign exchange, and a larger group of nations in Central America and Africa count on coffee for a significant portion of their income.

Jaffee (2007: 45)

Reactions to these crises arose from a variety of fronts; dire economic developments combined with a rising feeling of social responsibility and global solidarity signified the birth of contemporary coffee activism. The contentious politics of the coffee commodity manifested around the 1940s and continues to contemporary times. Activists around the world have been challenging mainstream trade by protesting or offering alternative paths for trade with the aim of improving living conditions for coffee farmers in developing countries. The citizen in the global North has been strongly encouraged to take responsibility for the producer in the global South. This is the story of coffee activism in the political arena.

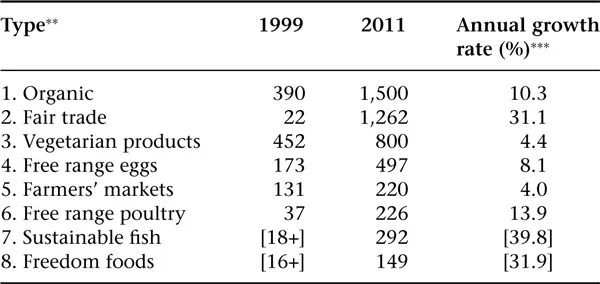

In the market arena, fair trade has been a success story. Since the beginning of the late 1990s the growth of the fair trade market has shaken its perception as niche (Chapter 2). There is overwhelming evidence to suggest that there has been significant growth in the fair trade market. Put modestly, fair trade sales have boomed during the 2000s. Fair trade is among the top three types of ethical consumption based on its market significance (Table 1.1). In addition, its annual growth rate appears to be higher than that of the top two types (organic and vegetarian products).

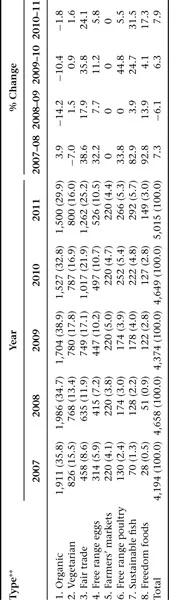

Fair trade has been moving into the mainstream; with supermarkets promoting their own brands of ethical products and corporations embracing the concept of a green/ethical lifestyle it is gaining significant promotion and reach. In order to examine the growth trend of the fair trade market closely, we need to study the available data for recent years in more detail. Table 1.2 illustrates the relative market share of each type of ethical consumption for each year between 2007 and 2011. This table also shows the actual growth rates in each period, 2007–08, 2008–09, 2009–10 and 2010–11.

Table 1.1 Growth of ethical consumption in the UK, 1999–2011 (£m)*

*Table 1.1 is assembled on the basis of data from the Ethical Consumerism Report 2009 and the Ethical Consumer Markets Report 2012.

**The types of ethical consumption are ranked on the basis of their market value significance (%).

***Calculated using the formula: [(ln2011 value – ln1999 value)/number of years] × 100.

+2005 values of growth rates for these categories are for the period 2005–11.

When comparing the top three types, whose upward trend is declining overall, fair trade follows a healthier upward trajectory (Table 1.2). Before and during the peak of the financial crisis, consumption of organic goods followed a declining, though slowly recuperating, growth trend, while vegetarian products demonstrated a slight imbalance in the rise and fall of their market growth. In contrast to these, fair trade accepted a less damaging hit during the 2008–09 period, while its growth rate ascended in the 2009–10 period. Despite the noticeable decline between 2008 and 2009 and the slighter sequent decrease during 2010–11, the growth of the fair trade market is comparatively higher than that of organic foods. For instance, the gradual annual drop of the fair trade growth rate from 38.6 per cent (2007–08) to 17.9 per cent (2008–09) is relatively smaller than the corresponding decline of organic foods from 3.9 per cent to a negative price of –14 per cent. This durable support to the fair trade market compared to the organic market demonstrates the particular strength of coffee activism in mediating cosmopolitanism (Chapter 6). In the particular case of the United Kingdom (UK), as opposed to the United States (US) and Canada, even during the economic crisis, fair trade sales did not wane as much as organic or vegetarian sales did (cf. Bondy and Talwar, 2011); the ethically consuming citizens I interviewed expounded unceasing support for the cause of coffee activism (Chapter 6). The sales of fair trade products such as coffee and bananas are booming in the mainstream market. As a result of successful campaigning, but also strategic promotion, the estimated annual UK retail sales of total fair trade products reached over a billion pounds,10 making any reference to the particular national fair trade market as niche sounds like an outdated understatement. Fair trade has conspicuously come into the market and the public mainstream. This provokes the question of whether there is a politics in the pocket, a politics which galvanises civic agencies through consumption, reinvigorates citizenship and changes the landscape of contention.

Table 1.2 Growth of ethical consumption in the UK, 2007–11 (£m)*

*Table 1.2 is assembled on the basis of data from the Ethical Consumerism Reports for the period 2008–12. Values in parentheses show cell values as percentages of column totals.

**The types of ethical consumption are ranked on the basis of their market value significance (%). Values in parentheses show cell values as percentages of column totals.

Shifting agendas and terminologies of the politics of consumption

I do think consumer power is enormous. I’m a big believer in that. I’m a big believer that you make a statement with what you buy, and where you buy and who you buy it from, massively, which is why, as far as I’m concerned, by encouraging people to buy fair trade that’s helping. That will also help push other political agendas, because the more people do it, the more successful it becomes as a money-making enterprise, the more it will become noticed.

(Melissa)

Through the pallet of issues of injustice and repression, political agendas are being pushed via bottom-up processes of contention. Against regressive state and market supremacy, austerity asphyxiation, human rights violations, poor labour conditions, environmental depredations and animal abuse, political agendas have become dispersed from official understandings of politics and resistance. A politics of resistance has reverberated across the world, from North America to Europe, the Middle East and North Africa, recon-ceptualised and rebranded as Occupy, Indignados and the Arab Spring. Beyond this, diverse strands of politics have increasingly been directed towards the market, addressing private actors, endorsing private actions and emerging in private arenas. Quoted above is an ethically consuming citizen, demonstrating that through the mobilisation of individuals, rather than collectives, the politics of consumption constitutes a reactive response to global political issues. Whether in the support of a company which pledges commitment to social and/or environmental justice or in the preference of a product that is certified as responsibly sourced, politics has become significantly appealing in the eyes of consumers.

Consumption has never before been so complex or charged with symbolic and material repercussions. The evolution of consumer activism has demonstrated that consumers have increasingly been demonstrating concerns about something other than price. Daily purchases have become so intricate that a stroll in the supermarket has become an expedition in a jungle of brands, reminders, hints and connotations of a range of (ethically labelled or not) choices. Political consumerism is a crucial phenomenon in the delineation of a contemporary politics of consumption. It extends beyond its negative form (boycotts) to its positive form (‘buycotts’) to signify acts of consumption which utilise the market arena to demonstrate political responsibility (Micheletti et al., 2004). For Micheletti, political consumerism represents ‘action by people who make choices among producers and products with the goal of changing objectionable institutional or market practices’ (2003: 2). Advocates of political consumerism recognise the swing towards a private arena for the enactment of an individualistic politics. Micheletti et al. (2004) cite a shift from a traditional model of participation in the political space to a model of participation in the market space that can be attributed to factors such as a disassociation with political life, resistance to other countries where human rights are violated (through boycotting) and to the free trade rule, and the asymmetrical growth between economics and politics, as well as the growing significance of consumer goods and consumption. A simple ritual such as getting a cup of coffee, whether you need an eye-opener before work or whether you feel like hanging out with friends, is filled with a plethora of connotations. You can either choose to buy a cup of coffee from Starbucks because you are attracted to the company or the array of choices, or you can choose not to perhaps because you have been exposed to information about the company or about the trade injustice charac-terising the second most imported product after oil; coffee is ‘black gold’ (Wild, 2004) and you can choose to consume it responsibly.

Yet, what constitutes the politics of consumption is debatable (Clarke, 2008). Beyond political consumerism, a growing grammar has been associated with the politicisation of consumption, particularly evident in the comparative terms ethical (Barnett et al., 2011) or radical (Littler, 2009) consumption or consumerism. There are only slight conceptual differences between these terms; the terms political and radical consumerism emphasise a more civic form of engagement, while the terms ethical and socially conscious consumerism describe a more civic form of consumption. There is a distinction to be made between the phenomenon of political consumerism and that of ethical consumption. The fundamental difference between the two is that the first one is a prerequisite for the second, while the second is not necessarily inherent in the presence of the first. Therefore, while ethical consumption refers to the broader phenomenon of ethical behaviour in the marketplace, political consumerism accounts for the politicisation of citizens through ethical purchasing. Political consumerism is admittedly a Janus-faced phenomenon; it is both a new form of market choice entrenched in attempts to carry ethics into the marketplace and a new form of participation in the political space. If the correlation between political consumerism and political participation stands, then the restructuring of the terms of ethical consumption affects the restructuring of political participation. In other words, consumer power is not always granted when embarking on ethical choices. At the same time, as Lang and Gabriel point out, ‘the rich literature on consumers, consumerism and consumption all thrive on . . . [a certain] ambiguity’ (2005: 39). This ambiguity concerns the agency of consumers as active or passive to market forces. It is, then, questionable to what degree the politics of consumption is blurred by the vagueness of the market. Political consumerism has been theorised as a form of political participation in the market, but has not been extensively examined in terms of the restrictions posed by its contextualisation in neoliberal times. A private arena such as personal choice in the marketplace enables public forms of political expression in the case of ethical consumption, but certain conditions must be met for there to be a substantial impact of those actions in the political arena.

Additionally, what constitutes an understanding of and distinction between fair trade and free trade is not unanimous or uncontested. As a model and movement for development, fair trade was historically adversarial to the free trade model and policies. In the trade of coffee, the fundamental capitalist logic of supply and demand through free trade agreements has been disparaging of coffee growing communities in the global South. As a response to this, the fair trade cause has sought to provide an alternative model of trading and mobilise consumers for change. Meanwhile, the corporate sector has been increasingly adapting to reflect responsibility in the global commons; fair trade has been emphatically embraced by corporations in their social-change agenda. Both corporations and coffee activists have expounded positivity for this interpolation. Starbucks, the coffee giant, now solely sources fair trade coffees in the UK and Ireland, while for Harriet Lamb fair trade is ‘about transformative business models’.11...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables and Figures

- Acknowledgements

- List of Abbreviations

- 1. Understanding Coffee Activism, Ethical Consumption and Political Consumerism

- 2. A History of Mainstreaming the Fair Trade Market and Movement

- 3. Politics in the Marketopoly: Cultural Citizenship and Political Consumerism

- 4. In Politics I Trust: Individualisation and the Politics and Pleasures of the Self

- 5. A Liquid Politics: Structures and Narratives of Participation in Digital Coffee Activism

- 6. Digital Media, Space and Politics: Cosmopolitan Citizenship in Coffee Activism

- 7. A Politics in the Pocket?

- Appendices

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index