- 214 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"

First rate popular history/biography, evoking the Byzantine empire at its peak. A remarkable story in an entertaining, informative book." —

The

Wall Street Journal

This is the biography of a Byzantine courtesan who rose from the gutter to the throne of an empire. It is a romantic and improbable story, and Theodora is an extraordinary woman, indeed. Her background and her many actions were scandalous, but she had qualities of greatness and this book sets the record straight. This account of her life is a pageant in which Emperors and barbarian kings, Popes and Patriarchs, eunuchs and generals, heretics and orthodox opponents, charioteers and ladies of easy virtue, saints and sinners move in a formal and splendid rhythm. This formality was often marred by violence: one of the worst riots in Byzantine history took place when Theodora had been empress for a short time, and during much of her reign there was war in Italy, marked by appalling suffering and barbarity. Toward the end of her life, Constantinople was devastated by Bubonic plague. Yet Theodora triumphed over every adverse circumstance, tough and clever to the end.

" . . . Bridge's book, with its exceptionally vivid and evocative style, brings the period alive." — Library Journal

"Puts [Theodora] in her own time and place in the vast panorama of the golden age of an empire which lasted 1,100 years." — Boston Herald

"Conveys the passion and the fervor of the sixth century A.D." — Los Angeles Herald Examiner

This is the biography of a Byzantine courtesan who rose from the gutter to the throne of an empire. It is a romantic and improbable story, and Theodora is an extraordinary woman, indeed. Her background and her many actions were scandalous, but she had qualities of greatness and this book sets the record straight. This account of her life is a pageant in which Emperors and barbarian kings, Popes and Patriarchs, eunuchs and generals, heretics and orthodox opponents, charioteers and ladies of easy virtue, saints and sinners move in a formal and splendid rhythm. This formality was often marred by violence: one of the worst riots in Byzantine history took place when Theodora had been empress for a short time, and during much of her reign there was war in Italy, marked by appalling suffering and barbarity. Toward the end of her life, Constantinople was devastated by Bubonic plague. Yet Theodora triumphed over every adverse circumstance, tough and clever to the end.

" . . . Bridge's book, with its exceptionally vivid and evocative style, brings the period alive." — Library Journal

"Puts [Theodora] in her own time and place in the vast panorama of the golden age of an empire which lasted 1,100 years." — Boston Herald

"Conveys the passion and the fervor of the sixth century A.D." — Los Angeles Herald Examiner

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Theodora by Antony Bridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PREFACE

One of the most glaring gaps in most people’s knowledge is their almost total ignorance of the thousand years of Byzantine civilisation, without which neither western civilisation as we know it nor that of Russia and eastern Europe could have existed. They have heard of Constantine; they know that at some time or another he transferred the capital of the Roman world from Rome on the banks of the Tiber to Constantinople on the shores of the Bosphorus, though few of them have much idea of when or why he did so. Most people have also heard of Justinian, though they are very vague as to when he lived and what he did. Lastly, the name Theodora is faintly familiar and has slightly naughty associations; but that is all. The rest, as Hamlet said in a very different context, is silence.

This remarkable ignorance is at least in part the fault of Edward Gibbon, paradoxical as that may seem, for he wrote the first and in many ways the greatest history in the English language of Byzantine civilisation; but he was so blinded by the enlightenment of his age that, in the process, he misrepresented Byzantium and misjudged it more completely than anyone else, and was thus responsible for the universal contempt in which all things Byzantine were held for over a century, and the almost equally universal neglect with which they were treated. Happily, however, within the last hundred years there has been a change of heart amongst historians, many of whom have reassessed the Byzantine achievement, rejecting Gibbon’s judgement of it. At the same time, the ease of travel which everyone now enjoys and the excellence of modern means of reproducing paintings and mosaics in colour have led to the rediscovery of Byzantine art, which is probably more widely and deeply appreciated today than it has been since the days of men like Cimabue and Giotto, and this in its turn has led to a rebirth of curiosity about Byzantine civilisation and history. Unfortunately, this curiosity is not very easily satisfied; few people can return to the original Greek sources of information, even when they are easily accessible, which with a few exceptions they are not; meanwhile, most of the standard works on the subject in English, French, and German, let alone those in Russian, are either difficult to obtain or rather daunting in appearance by reason of their size, their obvious erudition, and sometimes their cost. So many ordinary, interested, and intelligent readers decide that Byzantine history is not for the likes of them; they would probably enjoy it greatly if they read it, but they seldom do so, and this is a pity.

Indeed, it is because I think it such a pity that I have written this book, which is intended for the person who would like to know more about the civilisation of which Byzantine art was the mirror and the people of whose hopes and dreams and beliefs it was the expression and the glory. To get to know a civilisation you can do one of two things; you can take a sweeping bird’s-eye view of it, or you can focus your historical telescope on one period of it in all its variety, colour, and living detail. It is probably a good idea to do both, but you can only do one or the other in a single book, and I have chosen to look at the life and times of Theodora in as much detail as is available, partly at least because there is so much of it; for the events of her life and time are extremely well documented. Her contemporary, Procopius, a brilliant if at times violently prejudiced historian, who copied the style of Thucydides, left a mass of detailed information about her personally and about the events of her day in a large number of works, and he was by no means the only man to do so. Several other Greek historians, notably John Malalas, covered the same period, as did the Syriac historian John of Ephesus. Their works, as well as a mass of other contemporary documents of one kind or another, have been the sources to which all modern historians have returned, and the results of their labours have been legion. I have listed many of these modern histories, both of the particular period covered by this book and of Byzantine civilisation in general, in the bibliography at the end of this book, but I must acknowledge here my debt to two men: the French historian, Charles Diehl, whose biography, Théodora, Impératrice de Byzance, together with his history of her time, Justinien et la civilisation byzantine au VIe siècle, and his many other works are still invaluable, even though most of them were published sixty or more years ago, and Diehl’s equally great English contemporary, J. B. Bury, whose Later Roman Empire is not only a classic but also a mine of information about the life, times and contemporaries of both Justinian and Theodora. Of course, I am in the debt of many others too, but they must forgive me if I do not mention them all by name here.

As for my own book, it is in no way a work of original scholarship, as any historian will be able to see at a glance; I have picked the brains of other scholars and raided their works unmercifully, and I am grateful to them for the wealth of detailed information and local colour which they have provided. If my book manages to rouse the enthusiasm of some people for the Byzantines and their achievements, and thus encourages them to take a greater interest in one of the world’s greatest, yet most misunderstood and undervalued civilisations, I am sure that its real historians will forgive me for raiding their territory and invoking their assistance in the process.

A.B.

II

The Hippodrome was theirs. It was a place dedicated to passion, violence, group aggression, mob excitement, and the shedding of blood; for fights staged between men and animals and between animals themselves were almost as popular as chariot racing, and roused much the same sort of blood lust in the spectators as the old gladiatorial contests had excited before they were abolished by Theodosius the Great in the fourth century. Apart from the officials of the two factions, the Blues and the Greens, who managed the day-to-day business of the place, the permanent staff were mostly illiterate and uncouth, while those who hung around the fringes of the circus were often from the dregs of society. Here Theodora was born, and here she spent her childhood. It is difficult to imagine how she could have picked up a ready-made set of conventional middle-class morals in such a setting during the course of her early life, and this is something which her many pious detractors have usually chosen to forget or ignore. It was a time better suited to teaching her how to hold her own and survive in a human jungle, where toughness, courage, a quick wit, and shrewd judgement of people were more valuable than a nice ethical sensitivity; and these were qualities which she did indeed exhibit in later life.

She was not an only child. She had an older sister, Comito, and in due course another girl was born and named Anastasia. It used to be said that the family came from Cyprus, though more recently Syria has been suggested as their place of origin; the fact is that no one knows for sure where they came from. As if their circumstances were not already bad enough, shortly after the birth of the youngest child, when Theodora was about four or five years old, the father of the family died. Nothing is known about his wife, but the death of her husband, Acacius the bear-keeper, must have been a bitter blow to her; for, if it is seldom easy for a widow to bring up three children alone and unaided, it was an even more formidable task in the cut-throat world of the Hippodrome in Byzantium. With commendable speed and good sense, if with little regard for conventional ideas of mourning or morality, she quickly found another man to take her dead husband’s place as bread-winner for the family. Whether she married him is not known, but she started to live with him in the hope that she would be able to secure her late husband’s job for him. In order to do so, the manager of the Greens, a man named Asterius, had to be persuaded to appoint him, and unfortunately for the widow, he had already accepted a bribe from someone else who wanted the job. So when the unlucky woman sought an interview with Asterius and begged him to make her new consort bear-keeper, she discovered that she was too late.

This could only have been a tragic disappointment to the mother of the three small children. She could not hope to out-bid the other candidate for the post by offering a larger bribe than his, even if Asterius would have accepted it, for she had no resources; but she could make a bid for the support of the ordinary members of the Green faction in the hope that they would help her in her extremity, and this she decided to do. So one day when the Hippodrome was packed with people waiting for the races to begin, she appeared in the arena with her three small daughters; driving them before her, their heads crowned with little chaplets of flowers and their hands held out in supplication, she explained her plight and that of her children to the crowd, begging the Greens to employ her daughters’ new father so that the family might not starve. Appeals of every kind, including appeals to the Emperor himself, were not uncommon on such occasions, and they were made through a spokesman trained for the purpose. There could seldom have been a more touching appeal than this, but it left those to whom it was addressed completely unmoved; indeed, the Greens roared with laughter, and both mother and children were driven back whence they had come with their ill-judged merriment ringing in their ears.

The Blues, however, who were always on the look-out for ways of winning supporters away from their rivals, saw a chance of scoring a few points off them by offering the family employment similar to that which they had lost, and they promptly offered Theodora’s stepfather a job, thus solving the immediate problem. In all probability they then forgot the whole thing, dismissing it as one more trivial brush with the Greens and of no great consequence; but the long-term consequences of the whole affair were enormous, for Theodora never forgot the humiliation inflicted on her and her family on this occasion. For the rest of her life she was bitterly hostile to the Greens. This is not surprising when the probable impact of such an event on a child of four or five is estimated; it must have been shattering. The mother must have rehearsed the children in their part, and like all children they must have been excited, nervous, and desperately anxious to please and to succeed. When eventually they ran out into the arena and found themselves the sole objects of attention by perhaps as many as a hundred thousand pairs of eyes, they would hardly have been human if they had not been overcome with a mixture of terror and determination to do their part as well as they possibly could. Their feelings, when they found themselves assaulted by waves of mocking laughter and knew that they had failed, do not bear thinking about, and when they were chased from the arena in ignominy with their mother, their bewilderment at the injustice done to them must have been as unbearable as their sense of rejection and injury was memorable.

Nothing else is known of Theodora’s early childhood. According to Procopius, however, who is our only source of information about this time of her life, a little later, when she was of an age to do so, her sister Comito went on to the stage as an actress; probably this was when she was about fourteen or fifteen, and Theodora was eleven or twelve. At the time, the stage was regarded as a proper place only for the lowest of the low, and the profession of an actress was treated as much the same as that of a prostitute. For instance, in common with anyone who had ever been a servant girl, a barmaid, or a whore, girls who had been on the stage were forbidden by Roman law to marry senators or anyone else of high rank. For obvious reasons, however, such legal disincentives were unlikely to deter anyone born in the Hippodrome and brought up amongst the dregs of society, as were Theodora and her sisters, from embarking on any of these careers; few other occupations were open to them, for one thing, and for another their chances of marrying anyone of exalted social position were so small as to be negligible. So probably Comito had no misgivings about adopting the stage as a way of life, with all that such a decision implied. It is possible, even probable, that her mother had been on the stage in her younger days, or had been employed in one of the many side-shows which clustered round the circus, and that Comito was simply following in her mother’s footsteps; but this is conjecture. What is certain is that, although at first she was given only the smallest parts in bawdy plays or slapstick farces, it was not long before she became a minor success.

The Byzantine theatre in the sixth century had long ceased to resemble the Greek theatre in the days of such men as Euripides and Aristophanes, from which it was separated by nearly a thousand years of history, and indeed so had the Roman theatre before it. The plays in which Comito appeared were as unlike one of the great Greek tragedies or comedies of the fifth century B.C. as a performance in a London or a New York strip-tease club is unlike a play by Shakespeare. All Comito needed in order to be a success on the stage of the day was to be pretty, uninhibited, and unembarrassable; and while she had been lucky enough to be born pretty; there was perhaps some poetic justice in the fact that the misfortune of being born in the Hippodrome could at least be set against the fact that there was nowhere else on earth better adapted to teaching anyone to be both wholly without inhibitions and almost proof against embarrassment of any kind. Meanwhile, Theodora went along with her as a dresser, and even appeared on the stage with her, dressed as a young slave in a short tunic and carrying a stool on her head for her sister to sit on. She must have been an engaging child at this time, as pretty as Comito and with an impish sense of humour, for it was not long before she was making the audiences roar with laughter by pulling faces and making childish and vulgar gestures to please them. As sharp as a needle, she picked up the ways of the theatre with precocious rapidity, and soon she was given minor parts of her own. As a result, by the time she was fifteen or sixteen she had left Comito behind her and was fast becoming the star of the Byzantine theatre in her own right, with a growing reputation for daring immodesty.

Her success seems to have been due at least in part to her appearance. She was no longer the gamine little creature she had been a few years previously; she had developed into a ravishingly beautiful girl with a lovely if diminutive figure, a small oval face with huge dark eyes, a skin as smooth and almost as pale as ivory, and a miraculous grace and vivacious charm which even her worst enemies acknowledged to be irresistibly attractive. ‘To express her charm in words or to embody it in a statue would be, for a mere human being, altogether impossible,’ Procopius said of her in one of his public works, though he hated her, and even in his vicious Secret History he admitted that she was ‘fair of face and in general attractive in appearance’. She could not sing; she played no musical instrument; she had no talent as a dancer; and she could not act in the usual sense of that term; but she had a ready wit, a flair for making people laugh, a perfect sense of timing, and a genius for stripping with such suggestive and consummate indecency that the whole of Constantinople flocked to see her with mixed delight and shocked disapproval. According to Procopius, she did her various acts without the smallest scruple or inhibition and with great inventive bawdiness. For example, part of her repertoire was a comic burlesque of the story of Leda and the Swan, during which she would lie on her back on the stage with virtually nothing on, while a domestic goose pecked at some grains of corn secreted between her thighs, and she rolled about in an amorous frenzy, wriggling and twisting and grimacing in an apparent paroxysm of abandonment, to the uproarious delight of her audience. Some people were outraged, but they came in their tens of thousands to see her nevertheless, and she soon became the talk of the town.

But the stage was not the scene of her most notorious exploits. Procopius discharged his heaviest moral broadsides at her for supplementing her earnings in the theatre by becoming a highly successful and highly paid courtesan in her spare time. Her supper parties, he said, were a scandal, and the things which she was prepared to do for the men upon whom she bestowed her favours were infamous. Indeed, her unsavoury reputation and notoriety are based largely on Procopius’ highly coloured and lurid account of her sex life at this time; some historians have hinted at it coyly without going into detail, while others have quoted Procopius in his original Greek on the rather specious grounds that such details ‘must be veiled in the obscurity of a learned language’, as Gibbon put it, as if pornography was suitable reading for those with an academic training and for no one else. In fact, what Procopius said about her was that she was both sexually insatiable and also perverse.

She was extremely clever [he wrote], and had a biting wit, and she soon became popular as a result. There was not a scrap of modesty about her, and no one ever saw her embarrassed; she would do the most shameless things without the smallest hesitation, being the sort of girl who, if you slapped her bottom or boxed her ears, would make a joke of it and roar with laughter: and she would strip herself naked and exhibit bare those parts of her body, both before and behind, which are properly hidden from men’s eyes, and should be so. She used to titillate her lovers by keeping them in suspense, and by constantly toying with new ways of making love she never failed to capture the interest of the lecherous; nor did she wait for men to accost her, but she took the initiative herself by wiggling her hips to attract their attention and by cracking suggestive jokes to all who came her way, especially if they were still in their teens. No one has ever been such a total slave to sexual pleasure and indeed to all forms of pleasure as she was. Often she would go to a party with ten young men or even more, all of whom were at the height of their physical powers and devoted to a life of sexual indulgence, and she would sleep with every one of them, one after the other, throughout the night; then, when she had exhausted all of them, she would proceed to seduce their servants, even if there were as many as thirty, lying with each of them in turn; yet even so she would end the night unsatisfied … Moreover, although she pressed into service three entrances into her body, she often complained that nature had not made the openings in her nipples larger so that she could have invented a new way of making love there too. Naturally, she often became pregnant, but nearly always she managed to have an abortion.

This deliberately sensational picture of Theodora as a raging nymphomaniac is difficult to reconcile with what is known of her later life, but it would be foolish to react against it by trying to whitewash her altogether; it is no good pretending that she was a paragon of virtue at this time, for it seems sure that she was no such thing. There are some grounds for believing that at the age of about sixteen she had an illegitimate son, though there is no unimpeachable evidence to prove this; but there can be no doubt at all that at about eighteen she had an illegitimate daughter, for much of the girl’s subsequent career is well known. So there is probably some truth in Procopius’ account of her life at this time. But even so for two reasons his Secret History must be taken with a large pinch of salt where it speaks of Theodora: first, he does not claim to have been one of her lovers, and so his detailed account of her sexual practices can be based on nothing more substantial than lascivious gossip and malicious tittle-tattle, neither of which is a source which inspires much confidence; and secondly, every line of his narrative reveals the hatred with which he wrote it as well as the fact that he himself was very obviously not without his psychological problems. He loathed Theodora with a neurotic and obsessional loathing which drove him to accuse her and the man whom she later married, whom he also detested, of being possessed by devils. ‘These two peo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- Theodora

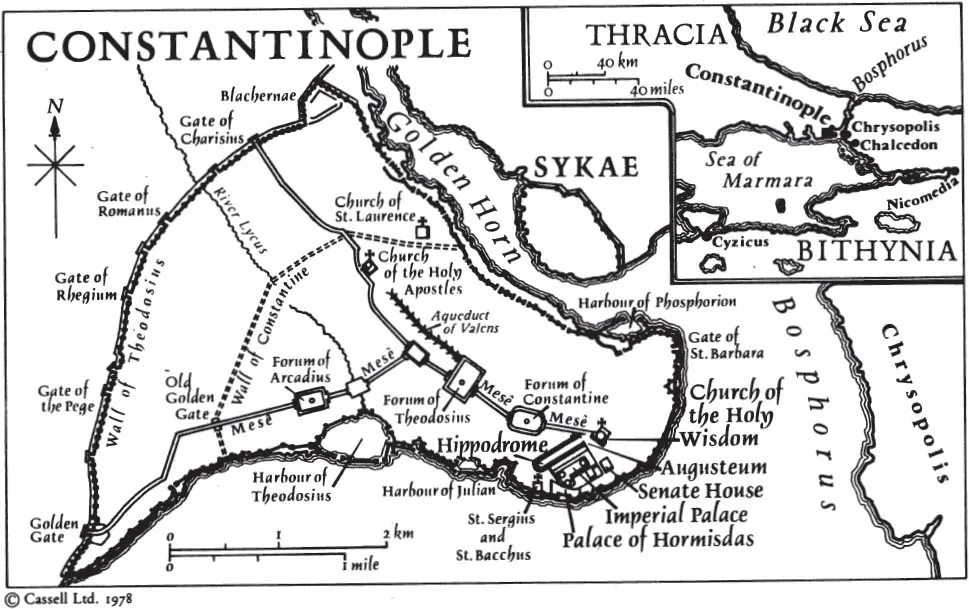

- Maps:

- Bibliography

- Timetable of Events