![]()

7 Cadbury: is it Camelot?

Leslie Alcock and Geoffrey Ashe

Ill. 99

Ill. 97

SOUTH CADBURY CASTLE, to give the place its full name, crowns an isolated hill about 500 feet high near the Somerset-Dorset border. The hill is composed chiefly, if not entirely, of Inferior Oolite limestone. There has never been a castle here in the medieval sense. The top is occupied, and the name accounted for, by a hill-fort of the pre-Roman Iron Age. An enclosure covering eighteen acres is surrounded by four defensive perimeters, one outside another. Massive banks and ditches, sloping at an average gradient of about 35°, encircle the hill most of the way down to the fields below. Today they are thickly wooded, with patches of nettles and, in the springtime, bluebells and primroses. Three ancient entrances cut through them. On the northeast, a path leads up from South Cadbury village to the one now most used by visitors. On the south-west, there is a much less clear path from Sutton Montis. The third entrance, possibly later than the others, difficult of access and disused, is on the east.

Ill. 96

The spacious grassy enclosure inside the earthwork is by no means flat. It rises, steeply in places, to a summit ridge with a long, level plateau. The highest point commands an impressive view across the low-lying Somerset basin, with Glastonbury Tor twelve miles away toward the Bristol Channel. On the east side, Cadbury Castle faces a recess in the nearby hills, the edge of the higher ground of Wessex. Before the Roman conquest, this district was on the fringe of the territory of the Durotriges and within easy reach of the Glastonbury lake village.

‘Cadbury’ is a name of uncertain derivation. Confusingly, there are other hills and earthworks so called. The ‘bury’ is Saxon. The ‘Cad’ looks like the principal syllable of a personal name which, if it is not also Saxon, could be one based on the Celtic cad, meaning ‘battle’. A. W. Wade-Evans proposed the semi-legendary hero Cadwy, or Cado, connected with Somerset in the Welsh Life of St Carannog.

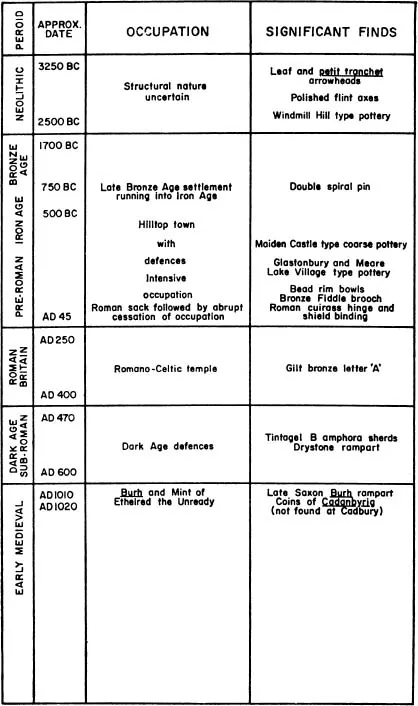

Ill. 95. Chronological chart of the occupation of South Cadbury Castle.

Not far off is the village of Queen Camel, formerly plain Camel. The belief that Cadbury Castle itself is Camelot can be traced back at least to John Leland, the Tudor antiquary. In 1542, he writes:

At South Cadbyri standith Camallate, sumtyme a famose toun or castelle. The people can tell nothing thar but that they have hard say that Arture much resortid to Camalat.

Leland, however, does appear to have heard a litde more than this. He notes tales about a silver horseshoe, ‘dusky blew stone’ carried off by villagers, and Roman coins turned up by the plough, both on the summit and in fields near the base. Other antiquaries repeat Leland without adding much. But Stukeley in 1724 mentions sling-stones, Roman camp utensils, and the ruins of arches, hypocausts and pavements.

Local Arthurian lore is rich. Some of it, though unrecorded by Leland, was apparently current in his time. The summit plateau at the crest of the ridge is ‘King Arthur’s Palace’. One of the two widely separated wells in the hillside is ‘King Arthur’s Well’. It is alleged that at the other, Queen Anne’s Well, you can hear when a cover is slammed down on King Arthur’s, and vice versa. This idea is one aspect of a more general notion that the hill is hollow. Rumours of a large cavern are numerous and recurrent. Somewhere there is an iron gate, or maybe a golden one, and if you come at the right moment it stands open and you can see King Arthur asleep inside. Some early archaeologists were accosted by an anxious old man who asked them if they meant to dig up the king. But Arthur does not always sleep. On St John’s Eve at midsummer, or perhaps on Christmas Eve, you can hear the hoofbeats of the horses as the king and his knights ride them down from Camelot to drink at a spring beside Sutton Montis church.

The Somerset Cam flows by in the middle distance. This is one of the conjectured sites of the battle of Camlann. Close to the western side of the hill, farm labourers once dug up some skeletons of men and boys, huddled together as if they had been pitched into a hasty mass-grave.

Ill. 101

Historically, the soundest fact is that from about AD 1010 to 1020, coins were being issued with the mint mark CADANBYRIG. Before that, everything is hazy. In 1890, the Reverend James A. Bennett, rector of South Cadbury, published a paper entided Camelot. Here he summed up the traditions and casually mentioned some digging he had done himself. When he ‘opened a hut-dwelling on the plain of the hill’, he saw a flagstone at the bottom, which the workman who was helping supposed—but not for long—to cover a manhole leading into the long-sought cave. Unfortunately, Bennett did not say where the hut was.

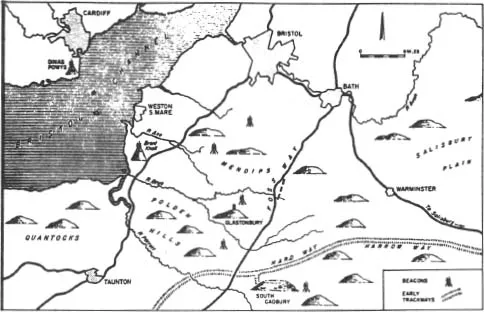

Ill. 96. Map showing South Cadbury and its environs. The beacons indicate possible line-of-sight communication between these places

The first properly recorded dig was carried out in 1913 by H. St George Gray, who had also worked on the lake villages. He sectioned the inner ditch, examined part of the south-west entrance, and trenched the summit plateau. Near the entrance he found the remains of a wall. Stone implements and pieces of pottery came to light. The excavation was neither extensive nor very thorough. But St George Gray recognised ‘late Celtic’ pottery and other artifacts akin to those from the Glastonbury lake village. While he found nothing to support the Arthur tradition, he expressed a wish to ‘learn more about Camelot, and to solve the many interesting problems which this wonderful stronghold presents’.

Ill. 100

Learning more about Camelot would clearly be a large undertaking. It was unlikely that sufficient interest or funds would be forth-corning till further evidence came to light to support the Arthur tradition and convince archaeologists that it deserved to be taken seriously. This was at last furnished during the 1950s by Mrs M. Harfield and Mr J. Stevens Cox, who patiently collected pottery and flints brought to the surface by ploughing. Dr Ralegh Radford picked out sherds of the significant Tintagel ware, together with a fragment from a Merovingian glass bowl. Commenting on this material, he observed that it provided ‘an interesting confirmation of the traditional identification of the site as the Camelot of Arthurian legend’. Pottery of the earlier Iron Age, and of NeoHthic type, was also recognised. Meanwhile, the growing of oats on the hill-top led to the appearance, in the summer of 195 5, of a rash of crop-marks showing where soil had been disturbed in the past.

Responding in November 1959 to a proposal for excavations, Dr Radford gave the inevitable answer that, without a sum of money running into thousands of pounds, the site seemed too big to handle. One would wish for buUdings, but the eighteen acres supplied no good clues as to where to look for them. At Castle Dore there had been nothing on the surface to show the whereabouts, or even the presence, of the dark-age structures below. However, the project was revived five years later as a result of a magazine article. By then, the financial potentiality was believed to exist. In June 1965, the Camelot Research Committee was formed, with Dr Radford as Chairman and Mr Geoffrey Ashe as Secretary. Sir Mortimer Wheeler later accepted the Presidency. It was composed of representatives of the Society of Antiquaries, the Society for Medieval Archaeology, the Somerset Archaeological Society, the Honourable Society of Knights of the Round Table, and the Pendragon Society. These were subsequently joined by the Prehistoric Society, the Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies, the University of Bristol, the Board of Celtic Studies of the University of Wales, and the Somerset County Council. The representatives included Mr Philip Rahtz and Mr Leslie Alcock, and, outside the list of contributors to this book, Lady Fox and Mr J. G. Hurst. Hence, the committee brought together a number of investigators in the dark-age field, and its programme could be counted as the first serious ‘Arthurian’ research of a concerted nature. But the terms of reference were strictly confined to the adequate excavation of this one site. The task was entrusted to Mr Alcock, and thereby came within the purview of University College, Cardiff.

A query arose at an early stage as to how much dark-age matter Cadbury was likely to yield. If it lay near the surface, the havoc of ploughing might have reduced its value to near-varushing point. Learned societies and professional archaeologists would be well satisfied with the Iron Age finds which could be confidently expected. But was the Committee justified in appealing for funds to a broader public, whose interests would be almost purely Arthurian ?

It was decided to begin with a reconnaissance on a small scale, and not too costly. This could be financed to a large extent by the learned societies themselves, and there could be no objection to seeking further funds for a ‘Quest for Camelot’ (as the operation was soon called) if its initial tentative nature was made clear. The Quest soon attracted interest. Money was provided by the British Academy, the BBC, Bristol United Press, Messrs Hodder and Stoughton, the Society of Antiquaries, the University College of South Wales and Monmouthshire, and a number of private donors.

Accordingly the plan went forward. The landowners, Mr and Mrs J. A. Montgomery of North Cadbury Court, gave their permission for excavation, and much help and kindness on the site.

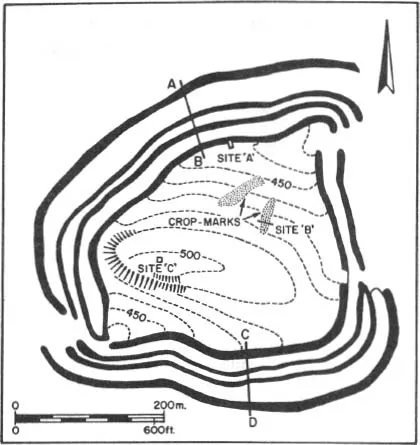

Ill. 97

The reconnaissance was carried out from July 15 to August 6, 1966. It was in two phases rurining concurrently: a survey and a trial excavation. The survey in turn fell into two parts. One of these consisted in making a contour plan of the eighteen-acre interior. Excavators would naturally hope to find traces of buildings. As it was out of the question to dig up the entire enclosure, some guidance would be needed in picking out the most promising areas. The clues from aerial photos, though interesting, were uncertain and insufficient. A contour survey might help both positively and negatively: positively, by showing which portions of the hill-top were the most level and suitable for building; negatively, by showing which portions could be written off because of the steepness of the slope.

From this point of view, the results were disappointing. The contour plan gave an excellent picture of the shape of the interior, with its summit plateau, the sides sloping down from this, and the level zone beside the rampart. It was all too obvious that only one small part of the hill-top, in the south-west, was wholly impossible for building. Nothing suggesting a terrace was detected. Terraces might have been blotted out by medieval and modern ploughing, but there were not even any traces, and on this topic aerial photography had nothing to add. Excavation was to show in due course that occupants of the hill were not deterred by a mere gradient from putting up houses.

Ill. 97- Co...