eBook - ePub

Fever and Thirst

An American Doctor Among the Tribes of Kurdistan, 1835-1844

- 354 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is "an enthralling account" (Booklist) of an American missionary doctor and his unprecedented adventures in Iraq, Iran and Kurdistan in the mid 19th century. The amazing thing about reading this richly detailed and absorbing account of the life and times of Dr. Asahel Grant in Asia is that things in that volatile region have not changed so very much over time. Gordon is a student of the region, having been in the Peace Corps in Ankara, Turkey in the 1960s, and readers come away with a nuanced and deeper understanding of the geography and dynamics of the region. This book, as one reviewer has said, "sheds tremendous light on our present-day misadventures in Iraq."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fever and Thirst by Gordon Taylor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

THE REMEDY

“To the place where the sun doesn’t come, comes the doctor.”

ON AUGUST 14, 1842, a man woke at dawn to find his face swollen into a bubble of pain. His beard, grown thick after months of mountain travel, probably masked the worst of the swelling; still, for one so lean of countenance this must have been a shock. A modern physician might name a dozen reasons, from food allergies to insect bites, why this could have happened; but the man had been ill for such a long time—six years, on and off, a recurrent round of vomiting and fever, broken by occasional spells of relief—that to him any new complaint must have seemed simply an extension of the old. He was not elderly—his thirty-fifth birthday was only days away—nor was he sickly by nature. Back in the United States, before he set sail for this remote corner of the Middle East, he had enjoyed the vigorous health of one raised to hard work on the family farm. But within a year after his arrival in Urmia, the town in northwest Persia where he first made his home, he had fallen ill. Only in the mountain air could he find a measure of relief.

When he felt the swelling, he identified the source immediately. That night he had slept in Chumba, a village on the river Zab, very close to what is now the border between Turkey and Iraq. His host, Malek Ismael, the chief of this Christian village, had given him the use of an arzaleh upon which to sleep. These structures, ten to fifteen feet high, were a common feature of life in the villages, where mosquitoes hatched in summer to supplant the winter’s crop of fleas. With the arzaleh, a sleeping platform set upon a framework of poles, the people sought refuge from the worst of the insects. The villages of this area abounded in water, which fed their terraced fields with torrents of melted snow falling from the mountains above. This particular arzaleh had been erected so close to such a stream that when the American climbed its rude ladder and lay down, his head rested only a few feet from a roaring cataract. The long-suffering traveler did not get wet; still, it was the proximity to dampness, he felt, that had brought on the swelling. This was no idle opinion, for the man was a physician.

Asahel Grant, M.D., a general practitioner from Oneida County, New York, was traveling in this wild border region between the Ottoman and Persian Empires under the auspices of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. In May 1835, aged 27 years, he had sailed from Boston with his bride, Judith, to teach the unlettered, preach the gospel, and heal the sick. Since then he had worked ceaselessly, traveling alone through mountains where the people lived in a constant state of feuding, robbery, and war. His character impressed everyone who met him, but his presence had changed this human cockpit not a jot. In fact, there is ample reason to believe that he had made matters worse. By January 1840, Grant’s wife Judith and twin baby girls—three-fifths of his family—lay buried in the mission graveyard in Urmia. Every year saw new deaths among the missionaries, some of whom were already dying when they arrived. And yet, faced by these and other losses, despite threats of robbery and murder, Grant rode on. He had not come to Hakkari, this untamed corner of Turkish Kurdistan, to allow something so trifling as a swollen face, or even so discouraging as a death, to hold him back.

On that Sunday morning Grant faced a five-hour climb to the zozan—the summer pastures—of Chumba, where Mar Shimun, patriarch of the “Nestorian” Church of the East, awaited his visit. Grant needed the patriarch’s friendship and approval; it was impossible to overstate the importance of this connection. The doctor had wearied of long marches through the mountains, so it was in the village of Asheetha, the center of a populous valley to the south, that he wanted to build a permanent home, a large house with many rooms where he and his missionary colleagues could teach and minister for the rest of their days. Through their efforts and with the patriarch’s support, the Church of the East, a tiny relic from the dawn of Christianity, would flourish again. Even the Kurds, Grant believed, might some day throw off the delusions of the False Prophet and receive the word of Jesus Christ.

When he arrived at the zozan, Grant found acres of sheep grazing amid alpine splendor. Most of the people of Chumba had retired to this summer camp in the high pastures with its invigorating air; they took shelter in crude huts made of branches or slept in the open on felt cloaks. The patriarch Mar Shimun, who occupied the only tent, gave a warm greeting to Dr. Grant, who had brought with him copies of the Psalms, printed in modern Syriac at the American mission in Urmia, the first of their kind ever produced. Mar Shimun accepted them with gratitude, and on that Sabbath afternoon he read the new books aloud as flocks grazed about them, shepherds kept watch for bears, and last winter’s snows seeped into the earth.

For six days of the week, armies of the sick and lame followed the doctor wherever he went; on this Sabbath he took time to minister to himself. We can only imagine the misery that beset him. His face remained swollen and painful; intermittent malaria drained his strength. Since 1836, when he had barely survived an attack of cholera, his stomach could retain food only fitfully. Now as a doctor, he knew one ultimate remedy for the swelling of his face.

This was neither a drug nor brandy, and certainly not a poultice or a salve. From his black bag Dr. Grant drew an object that, although no bigger than a pen, was the most potent weapon in the physician’s arsenal, used to attack all diseases, including diphtheria, malaria, and yellow fever, as well as childbirth, female disorders, and broken bones. This instrument took such precedence in the fight against disease that even today the journal of the British Medical Association bears its name. The lancet, as its name implies, resembled a tiny spear, with a double-edged blade tapering to a sharp point. It was used with small bowls to catch the blood. And surely that night, in the privacy bestowed by darkness, blood flowed freely. For his swollen face, says his biographer, Grant found relief “only by a desperate plunge of his lancet into the very roots of his teeth.” The blade, Grant admits, had struck so deeply into his gums that the labial nerve was severed, leaving his upper lip numb for nearly two weeks.

This was not the act of a madman or a quack. Grant was a competent and conscientious physician, a man who never acted with anything but the best of intentions. No one can read about his desperate thrust of the lancet without the queasy realization that little had changed since alchemists stalked the earth. In some parts of the United States, doctors continued to draw blood up to the beginning of the 20th century, and the potions they dispensed lingered even longer in their black bags and in apothecaries’chests. Such was the staying power of an illusion; such was the world of Asahel Grant.

2

UTICA AND BEYOND

“And I would never travel among Christians. Christians are so slow, and they wear chimney-pot hats everywhere. The further one goes from London among Christians, the more they wear chimney-pot hats. I want Plantagenet to take us to see the Kurds, but he won’t.”

“I don’t think that would be fair to Miss Vavasor,” said Mr. Palliser, who had followed them.

“Don’t put the blame on her head,” said Lady Glencora. “Women always have pluck for anything. Wouldn’t you like to see a live Kurd, Alice?”

“I don’t know exactly where they live,” said Alice.

“Nor 1.1 have not the remotest idea of the way to the Kurds … But one knows that they are Eastern, and the East is such a grand idea!”

IT BEGAN WITH A CHILD’S desk drawer, a wayward axe, and a life of hard work and Puritan religion. At the turn of the nineteenth century Asahel Grant’s parents, Thomas and Rachel Grant, had migrated west to New York from Litchfield County, Connecticut, an area known, wrote Rev. Thomas Laurie, Grant’s biographer, for “pure revivals” and the “sterling, intelligent type of its piety.” In Oneida County, atop an eminence known as “Grant’s Hill,” on the road between Waterville and Clinton, they built the Grant family homestead.

There on August 17, 1807, Asahel (“made by God” in Hebrew) was born, and there, in a youthful accident, he disqualified himself from a life of farming by slicing his foot with an axe. As if to compensate, he displayed an early interest in medicine, keeping an assortment of ingredients in a desk drawer for his own study and use. After a time teaching in a country school, Grant studied medicine in Clinton with Dr. Seth Hastings, after whom he named his eldest son. Later he audited a chemistry course at Hamilton College in the same town and attended medical lectures in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. As was typical of the time, Grant never received a formal college degree. Despite a proliferation of medical schools, most physicians learned their trade through apprenticeship with other doctors, without attending even a single course of medical lectures. Eventually Grant ended up in Utica, New York, where he studied surgery with a local doctor and married Electa Loomis, daughter of another pious Connecticut family. Most important, it was in Utica that he found missionary Christianity.

The “call” came on October 8, 1834, when the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions convened its twenty-fifth annual meeting at the Dutch Reformed Church in Utica. By then, at age 27, Grant was well established both as a physician and an elder in the First Presbyterian Church. After receiving his medical diploma, he had set up his first practice in what is now Laceyville, Pennsylvania. Upon Electa’s death in 1831, Grant returned to Utica to seek help in caring for his two sons, and set up a practice there with another physician, who eventually had to flee the town because of a financial scandal. Grant inherited the entire practice and prospered in Utica, a newly incorporated, rapidly growing city on the Erie Canal. In 1830, Utica had a population of “4,135 males, 3,968 females, and 183 colored.” The young doctor exhibited great courage and energy during the epidemic of Asiatic cholera which swept through Utica in 1832, causing some 3,000 people to flee the city.

By the time the American Board convened its meeting, Asahel Grant had become imbued with that devoutness so characteristic of 19th-century New Englanders. Rev. Thomas Laurie writes, “His piety was not of that spongy character that is dry and hard save as it absorbs moisture from without, and then refuses to impart it except under pressure. It was like the fountain, ever filled from the fulness there is in Christ, and ever imparting what it had to others.” In short, the man overflowed with energy, religious ardor, and idealism. “I cannot,” Grant wrote to a friend, “I dare not go up to judgment, till I have done the utmost God enables me to do to diffuse his glory throughout the earth.”

Part of the American Board’s 1834 convention dealt with reports of missions in the field, and one of these came from northwest Persia, where Rev. Justin Perkins, of Springfield, Massachusetts, and his wife, Charlotte Bass Perkins, had gone to open a mission to the local Nestorian Christians. At that point they had done little but survive the journey, which involved a long internment by thuggish Russian officials. Above all, they needed colleagues. “The Committee have sought in vain,” said the Annual Report, “for a pious and competent physician, able and disposed to go forth as an associate with Mr. Perkins … Such a man is exceedingly needed.” Confronted with this plea, Grant felt the call to service. For many weeks, he wrestled with his feelings. His two motherless sons would have to be left behind with foster parents; he had no wife to share his burdens; his practice in Utica was profitable, and his many friends implored him to stay. Yet such were his reverence and resolve that, one by one, the objections fell away. He found a good man willing to care for his children. The profits from his practice were nothing, he decided, compared to those that would accrue from God’s work. And very quickly, a woman entered his life.

Judith Campbell, seven years younger than Asahel Grant, had been orphaned at an early age and adopted by an aunt and uncle. She read Latin and Greek, spoke French and was, if anything, even more pious than the doctor. Thomas Laurie tells us that at age seven, when a missionary couple from an adjoining town left for the Sandwich Islands, Judith was persuaded to donate her favorite mittens to a gift box assembled by the ladies of her church. Such climatic naïveté may seem absurd; but it should not be forgotten that girls like Judith Campbell and other Protestant women of New England were formidable human beings—so devout, so fervid in their desire for education, progress, and self-sacrifice, that they formed the core and conscience of the Abolitionist movement, as well as the movement for women’s rights and suffrage.

Judith Campbell had already been accepted for missionary work when Dr. Grant met her, and in retrospect their union seems inevitable. By October 28, 1834, he had written to the Board asking to be accepted as a missionary, and as his plans matured over the winter, his relations with Judith matured as well. In February he wrote to a colleague, “You will rejoice to learn that a kind Providence has united with mine the heart of a young lady of most precious spirit, whose ardent piety, good health and highly cultivated intellect, fit her for extensive usefulness.”

Here the good doctor might seem to be describing a new employee rather than a fiancee. “Usefulness,” however, was high praise for someone of Grant’s convictions. Being useful—in God’s work—implied qualities of a far higher order than mere niceness or pleasantness. Grant could not have loved a woman who would not prove useful in the great labors ahead. For her part, in a letter to her brother dated March 10, Judith delivered a warmer assessment:

You know, dear brother, how much I have thought of being a missionary, and how I have prayed to know my duty in the matter. Hitherto the way seemed hedged up; but a door is now opened, and I am about to enter it. Yes, my dear, dear brother, I expect soon to leave these loved familiar scenes for Persia. The interesting ceremony that unites me with Dr. Grant takes place on Monday, April 6 … I wish you could become acquainted with Dr. Grant, for I am sure you would like him. He has been an elder in Mr. Aikin’s church three or four years, and bears the character of an eminent and devoted Christian.

Judith Campbell and Asahel Grant were married on April 6, 1835. On May 11, aboard the brig Angola, they sailed from Boston harbor for the shores of Turkey.

In 1835 the word “Turkey” was political shorthand, not an official name. The Ottoman Empire, like Saudi Arabia today, was named after a man, in this case Osman I, the Turkish gazi, or warrior, who founded the dynasty in 1299. There were several sobriquets for the Empire and its sultan—“the Grand Turk” and “the Grand Seigneur” among them—but commonly the central government was referred to as the Sublime Porte, or simply the Porte, after the gate which led into the inner reaches of the Topkapi Palace in Constantinople. The Osmanlis, as the Ottomans were also called, had once ruled a vast empire stretching from the Persian Gulf to the gates of Vienna, but by 1835 they were in retreat. In Iraq and the Arabian Peninsula, the Turks’ authority, loosely applied, remained, but in Egypt, nominally a part of the Empire, an Albanian soldier-of-fortune named Mohammed Ali had taken power, established a de facto independence and, after aiding the sultan in the Greek War of Independence (1821–28), had extended his authority into the Ottoman provinces of Palestine and Syria. When Mohammed Ali’s troops invaded Anatolia and routed the Ottomans at Konya in 1832, only the intervention of the Russian fleet kept the Egyptians from taking Constantinople. By the time the Grants arrived in Turkey, everyone knew that another war between Mohammed Ali and the Ottoman sultan, Mahmud II, was inevitable.

In the east, west, and north matters were even worse, for there the Turks faced the ever-growing power of the Russians. It had long been common knowledge that the czars were pushing south in search of a warm-water port, their obvious goal being Constantinople and the Straits. Between 1768 and 1878 the Turks and the Russians fought six major wars, and as these conflicts took their dismal course, the Turks’ possessions fell steadily away. On the north shore of the Black Sea, the Russians took the Crimea from the Tatar Khans. They absorbed the Kingdom of Georgia and were waging a war of conquest against the Muslim tribes of the Caucasus. In Rumania, Bulgaria, and the Balkans, Russian power was growing every year.

When Judith and Asahel Grant landed in Turkey in 1835 and sailed east on the Black Sea, to take the caravan route to northwest Persia, they were the direct beneficiaries of a Russian victory over the Turks. Before 1829, when Turkey was forced to sign the Treaty of Adrianople, the Dardanelles and the Bosphorus—and thus the Black Sea—had been closed to foreign shipping by decree of the sultan. After Adrianople, Turkey was open again to travel and commerce. Thus, only two years after the peace, two American missionaries, Eli Smith and H.G.O. Dwight, were able to cross Anatolia from Constantinople to Erzurum, past Mt. Ararat and into Persia. There, after much sickness and hardship, they made contact with local Nestorian Christians in Urmia and obtained the shah’s permission to open a school...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Introduction

- Maps

- 1 The Remedy

- 2 Utica and beyond

- 3 Miasma

- 4 The Last Dreams of Mahmud

- 5 Mosul and Mesopotamia

- 6 Into Kurdistan

- 7 Manna and Its Heaven

- 8 The Patriarch and the Kurd

- 9 The Arms of Urmia

- 10 Competition

- 11 Critics, Snipers, and Frauds

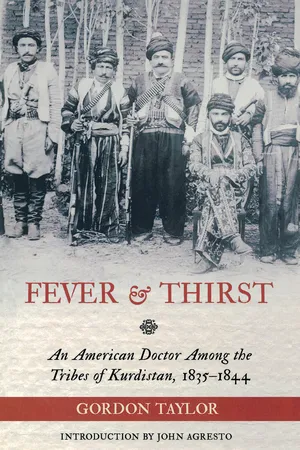

- Illustrations/Photos

- 12 The Pilgrim

- 13 Inferno

- 14 “Inductions Dangerous”

- 15 Demons and Angels

- 16 “Wars and Rumors of Wars”

- 17 The House in Asheetha

- 18 Mr Badger Drops In

- 19 Holding the Tigris

- 20 Devouring Fire

- 21 A Long, Steep Journey

- 22 The Monument in Asheetha

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Notes and Comment

- Bibliography

- Glossary