- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

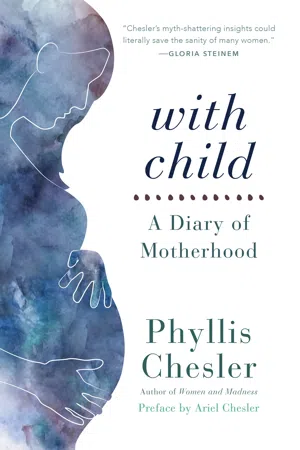

This diary of acclaimed psychologist and radical feminist Phyllis Chesler was a pioneering work when it was first published in 1979, and it still resonates today. It is a look into the second wave of feminism in the 1970s and the changing attitudes towards motherhood and pregnancy at the time.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access With Child by Phyllis Chesler,Ariel Chesler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

PREGNANCY

May 1, 1977

Child: How imperiously you make yourself known. This morning I vomited.

My teeth are chattering. My fear—such fear!—seems to rise up out of history, to swirl through my bowels, all the way up to my teeth. I’m afraid of you. Who are you, that I tremble so?

Why am I having a baby? How many women have asked themselves this question? Am I any different, any freer, than those mothers who never asked?

I am without the hystory of female askings. I ask as if for the first time.

I’ve heard mothers try to talk about pregnancy, or children, in the midst of “adult” conversation. Always, they risk indifference—from others with something “larger” to say. As if an individual tale of pregnancy isn’t important. As if all mothers—or children—are alike.

Little one: This journal will be a record of my askings; a record of our beginnings; a record of our awakening; a record of the fact that before you, there was me. Who in the middle of my life—in chaos—choose you.

Know that I’m terrified of the enormous responsibility.

What if I have to choose between my work and you—and can’t?

What if I can’t earn enough money?

What if I can’t transform myself into a mother-person?

Do all women die in childbirth to be reborn as mothers? Does your coming mean my death?

Why am I having you? Do I think you’ll always be there for me? Do I believe that only you, an unborn child, are my true beloved, my marriage mate, till death do us part? I do.

Why am I having you? Am I afraid I’d regret not becoming a mother? Have they finally gotten to me: those who say that all else for women is ephemeral, unsatisfying?

Have I lingered in your father’s arms, these many years, just waiting for you? Can I leave him, now that you’re here?

Am I bored with my work? Or is it the growing knowledge that I won’t be allowed to do my work, that has me turning to thoughts of you?

Listen, child: I hear them at my heels. My breath grows short. I choose you to throw them off my trail. I choose you so that when I’m next accused of daring too much, of wanting too much, of having too much (for a woman), they’ll pause, and see us—only a mother and child—and call off their inexorable laws.

Are you my cover? Can women hide behind children without becoming very small ourselves?

To embrace what has been is foreign to me. Women have always had children. Children have always had women. Despite this, despite everything I know, still I choose your existence. In doing this, I accept my own.

I am every woman who has dared to hope that despite everything, a child will sweeten her days, soften the blow of loneliness and old age.

I am every woman who has ever honored her mother by becoming a mother.

You are my emissary to the next century. You, child, are my life offering to all the mothers who have preceded me.

The great and greatly silenced Mothers. There’s a shelf in my local bookstore marked “Child Care,” with books by male experts on annual expected growth rates and separation anxiety; books praising natural childbirth; books damning obstetrical procedures in America. Here’s a book on how to form your own child care center.

Twenty books in all.

I find a handful of precious, brave books, all published in the last five years, by mothers on motherhood. Where are the thousand descriptions of pregnancy and labor, the dreams and consequences of mother-longings in every century, every culture?

Child: I’ll search for Mothers, dead and alive, to guide me. In dusty manuscripts, in new anthologies—in my living room or theirs.

May 8, 1977

On Mother’s Day, at dinner, I tell my mother I’m pregnant with you. “Oh,” she says, chewing slowly. “It’s about time.”

If my father were alive, he’d be shouting with excitement. He’d be crying. But there she sits, immovable as ever. I’m unprepared for such indifference.

I leave the restaurant, cheeks burning. How can she, of all women, not rejoice? Who, then, will rejoice with me if not my mother? Suddenly I’m returned to my childhood, to my search for mothering.

In becoming pregnant, am I hoping to find a mother rather than become one? Does a mother need a mother even more than a daughter does? But who’s the mother now, who’s the child?

My mother is my child. She’s herself, only in child form. (Like the nineteenth-century dolls with grown-up faces.) Her peevish dependence annoys me. I’m shocked by my own coldness. I dress her. I scold her for wetting her pants. She is me when I was a child. I am her.

Oh, child, I’ll have an abortion. I never want to feel such coldness toward another person. Definitely not toward you. It’s better we end it now. No, I’ll keep you—to spite her! In spite of her! Why should I let her come between us?

You’ll be my mother, my family! (Is this why women have children?)

Baby: Your grandmother hardly ever laughed. She trusted no one, expected nothing. She was always “doing something”: the dishes, the cooking, the shopping. She was either dressing one child or taking another to school.

She was always avoiding being alone with me.

Once it must have been different between us. Before my first brother was born: when there were only the two of us alone together all day, every day, for three and a half years. I can’t remember having her. I only remember losing her.

May 10, 1977

Since 1971 I’ve received eight thousand letters from people, sharing their lives with me, asking me for advice. Whom should I write now? Who will answer my questions? Who will believe that I don’t have the answers? Who will believe that I’m so scared?

Suddenly, women in the “ordinary”—mothers—seem wise to me. Mothers must know what I need to know. I’m going to begin asking the mothers I know all the important questions.

Will you and I love each other?

Will we really love each other?

What happens if we don’t?

Who will mother me, so that I can mother you?

May 11, 1977

Coffee with Doris, the mother of two daughters in their teens.

“How did you do it?” I ask. “Who helped you?”

“Only my mother—and my husband when he could,” she tells me. “My mother lived in my building. I could leave the baby with her when I wanted a coffee break.”

“No one else helped you?”

“Phyllis, who do you expect to help you? No one helps mothers. That’s what a mother does: help others.”

“Oh.”

She toasts me with cappuccino.

“I wonder how different things will be for you. Probably not much. But who can tell?”

May 15, 1977

Sitting on my couch, another mother. Angie married the “right” man, became rapidly pregnant in her early twenties, has three children under ten. She must know what I need to know.

“Who helped you?” I ask. “How did you manage so many kids all at once?”

“So you’re really doing it.” She smiles at me with admiration. And affection. “Who helped? I helped! That’s it. That’s the whole story. My mother made me crazy: I wouldn’t let her into the hospital after I gave birth. My mother’s attitude was: I did it alone; no reason you can’t. She didn’t think I should ever have a baby-sitter. Mothers belong at home, not strangers. My husband was busy; he helped weekends. But I was really alone for five years managing three kids.”

“Swallowed up alive is that it? Never alone, but always alone?”

“Something like that,” she replies cheerfully. “And, Phyllis, labor hurts like hell. Don’t let them lie to you about taking deep breaths and—presto!—here’s a cute baby.”

“Oh.”

May 17, 1977

“Darling, it’s the task of Sisyphus—but what isn’t? My son is a pleasure, a joy, a real companion.” This is Stella speaking, a new mother twenty-five years ago.

“Once you’re a mother you’re always a mother, no matter how old you are or how old they are.

“My oldest daughter doesn’t speak to me at all.” She tells me this for the first time. “She hasn’t for four years. Her analyst thinks I’m the original monster mother. It took me four years to stop trying to reach her. Maybe she’ll never speak to me again.”

“Does she see her father?” I ask.

“Not really. But she does go to him for money. She couldn’t get as much from me. I can’t earn as much.”

Oh. Some children never speak to their mothers again. Years have gone by when I haven’t spoken to mine….

“Stella, who helped you with your children when they were very young?”

“My mother would have. She would have done everything for me. But she died three months after I got married. I had to struggle alone.”

May 18, 1977

Another mother and I sit in a restaurant. Nora’s son is eight years old. We touch each other in excitement.

“Phyllis, I’m so pleased! I’ve been wondering for a while now: which of the “early warriors” would decide to become a mother—after feminism. And it’s you.”

“Who helped you, Nora?”

“Help? Oh, my dear. Don’t be absurd. My mother is completely impossible. And movements can’t be relied on. I couldn’t count on comrades with no time, who were actively hostile to children. My husband and some of his male friends were my child care support network…. Will you breastfeed?” she asks.

“Of course,” I reply. “Sure. But how do you travel to lectures and breast-feed too?”

“Good question. You take a nasty little breast pump with you and squeeze your milk out in the lonely motel room so that your breasts don’t ache—and your milk supply doesn’t dry up. You try not to miss the baby too much. You try not to think that your presence is more essential than his father’s. You try not to be guilty. You...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- New Preface

- Part One: Pregnancy

- Part Two: Childbirth

- Part Three: Motherhood

- Epilogue

- Afterword