eBook - ePub

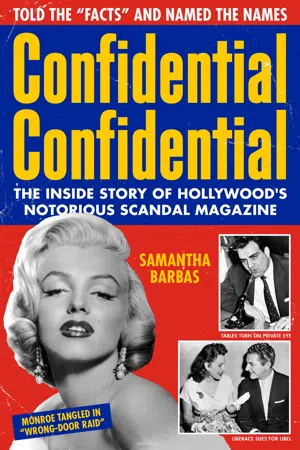

Confidential Confidential

The Inside Story of Hollywood's Notorious Scandal Magazine

- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In the 1950s, Confidential magazine, America's first celebrity scandal magazine, revealed Hollywood stars' secrets, misdeeds, and transgressions in gritty, unvarnished detail. Deploying a vast network of tipsters to root out scandalous facts about the stars, including sexual affairs, drug use, and sexual orientation, publisher Robert Harrison destroyed celebrities' carefully constructed images and built a media empire. Confidential became the bestselling magazine on American newsstands in the 1950s, surpassing Time, Life, and the Saturday Evening Post. Eventually the stars fought back, filing multimillion-dollar libel suits against the magazine. The state of California, prodded by the film studios, prosecuted Harrison for obscenity and criminal libel, culminating in a famous, star-studded Los Angeles trial.

This is Confidential's story, detailing how the magazine revolutionized celebrity culture and American society in the 1950s and beyond. With its bold red-yellow-and-blue covers, screaming headlines, and tawdry stories, Confidential exploded the candy-coated image of movie stars that Hollywood and the press had sold to the public. It transformed Americas from innocents to more sophisticated, worldly people, wise to the phony and constructed nature of celebrity. It shifted reporting on celebrities from an enterprise of concealment and make-believe to one that was more frank, bawdy, and true. Confidential's success marked the end of an era of hush-hush—of secrets, closets, and sexual taboos—and the beginning of our age of tell-all exposure.

This is Confidential's story, detailing how the magazine revolutionized celebrity culture and American society in the 1950s and beyond. With its bold red-yellow-and-blue covers, screaming headlines, and tawdry stories, Confidential exploded the candy-coated image of movie stars that Hollywood and the press had sold to the public. It transformed Americas from innocents to more sophisticated, worldly people, wise to the phony and constructed nature of celebrity. It shifted reporting on celebrities from an enterprise of concealment and make-believe to one that was more frank, bawdy, and true. Confidential's success marked the end of an era of hush-hush—of secrets, closets, and sexual taboos—and the beginning of our age of tell-all exposure.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Confidential Confidential by Samantha Barbas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

1

THE EDUCATION OF A PUBLISHER

ROBERT MAX HARRISON, THE future publisher of Confidential, was born on April 14, 1904, in Manhattan. His parents, Benjamin and Pauline, had migrated from Latvia fourteen years earlier. Benjamin was born in 1867; Pauline Isralowitz was born in 1871. The name “Harrison”—after President Benjamin Harrison—was bestowed on them by an Ellis Island immigration official. A tinsmith by training, Benjamin took up work at the Duparquet, Huot & Moneuse Co., a well-known maker of heavy-duty kitchen equipment for hotels and restaurants. It was steady, well-paying work, and he held the position until he retired.1

In 1894 the couple had their first child, Helen. Gertrude was born in 1897. In 1899 the couple had their third daughter, Ida Ettie, who went by Edith. When Bob was born, the family lived in a tiny tenement apartment at 112 East 98th Street in a working-class neighborhood populated by German, Italian, Irish, and Jewish immigrants. A few years later the family moved to Hewitt Place in the Bronx, another poor immigrant area. By 1920 the family had relocated again, this time to a section of West 108th Street in Manhattan filled with high-density tenement buildings.2

Little is known about Harrison’s childhood; he said almost nothing about it. He did have an eager and early interest in girls. Harrison doted on neighborhood sweethearts and was an ardent fan of the pretty chorines and Ziegfeld girls who were pop culture icons in that era. Although Harrison was bar mitzvahed and raised in a religious family, he didn’t practice as an adult, and Judaism played little part in his life.3

Like most children of recent immigrants in New York at that time, Harrison spent hours on the street. The street was his playground and classroom; there he learned how to think on his feet, to fight, and to sell. Most poor immigrant kids worked odd jobs on the street—singing for pennies, running errands, peddling fruit, shining shoes. They grew up listening to the cries of street vendors and pushcart peddlers, learning that, in the words of historian David Nasaw, it was “the salesman’s job to pitch and the customer’s to resist.”4

Harrison was a born hustler—a “kid who always saw a commercial angle,” as he put it. At the age of ten, he watched subway riders exiting a station in a rainstorm. He set up an umbrella rental stand. It was his first business venture.5

When Harrison was fifteen he came up with a “magazine”—Harrison’s Week End Guide, a pamphlet listing hotels and other lodging for people taking road trips in New York and New Jersey. Automobiles were still a novelty back then; roads were just being developed, and most people weren’t familiar with hotels. He drew up the pamphlet and took it to a printer, who signed a publishing contract. It wasn’t long before he realized he’d been ripped off. The printer ran it off and “that was the last I ever saw of it,” he recalled. “That S.O.B. stole it from me. And I thought I was gonna make a lot of money on it.”6

Harrison went to public grammar school, then to Stuyvesant High School, just emerging as one of the city’s leading public high schools. He excelled at English but flunked math. High school education wasn’t required, and after two years Harrison dropped out to work as an office boy in an ad agency. His father opposed it. Religious and steeped in old-world values, Benjamin believed that a man should have a useful trade, like welding or carpentry. Advertising and publishing were just “air businesses,” he snickered. Harrison felt guilty about disappointing his father, and it pushed him to succeed in his publishing career. When he achieved fame with his magazines, he’d tell friends, “My father wouldn’t believe I’d ever be this important.”7

Sometime in his teens, Harrison discovered he had a passion and “flair” for writing. That interest took him to Columbia University, where he studied English and literature in the evening division. In 1921 he took his first job in publishing, as an office boy at Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. Three years later Harrison went to work on a scandalous new tabloid called the New York Evening Graphic.8

The 1920s was the great age of the tabloid in America. By the end of the decade, several cities had tabloid newspapers, with the most prominent and influential published in New York. Presented as cheap amusement for working-class audiences, tabloids offered readers a potent daily dose of crimes, mysteries, murder trials, and scandals announced with garish photos and ninety-six-point headlines. In an era of flappers, jazz, cars, and speakeasies—of urbanization, sexual liberation, and cultural upheaval—tabloids embodied the whirlwind mood of the times and the hard rhythm of the cities where they took root and flourished. Tabloids were the “journalistic mirror” of their time, wrote one critic. They were as “expressive of modern America as World Series baseball, skyscrapers, radio, . . . taxicabs, and beauty contests.” With gusto and abandon, they defied the norms and practices of conventional journalism, with its staid tone and dry, straightforward factual reporting. Unlike traditional newspapers, focused on politics, business, and world affairs, tabloids dealt in matters of the heart and everyday life, the “things that people talk about on the streets and in their homes.” Their animating principle was that “no matter what his background and education, a man is governed by his emotions.”9

The 1920s wasn’t the first time sensationalistic journalism had attracted an audience. The pre–Civil War era had the penny press, cheap newspapers offering fantastic tales of murders, seductions, and other urban mayhem. The 1890s saw “yellow journalism,” perfected by the Hearst press, with enormous scare headlines, lavish pictures, and blatant fictions offered as news. The National Police Gazette, a little pink paper described as the “greatest journal of sport, sensation, the stage, and romance,” was the forerunner of the 1920s tabloids. The Gazette, which crested between 1880 and 1910, was the first publication to feature divorce stories and to embellish newsprint with woodcut illustrations of such titillating subjects as bare-knuckled pugilists, showgirls, and gun battles.10

The New York Daily News, the nation’s first tabloid, debuted in 1919. In 1924 William Randolph Hearst launched a rival, the Daily Mirror, promising “90 percent entertainment, and 10 percent information.” Later that year Bernarr Macfadden introduced the New York Evening Graphic. Diminutive and muscle-bound, “a crazy Irishman with a mane of long hair,” a food-faddist and exercise junkie so obsessed with health that he was nicknamed Body Love, since the late 1800s Macfadden had published a string of magazines devoted to fitness, nudity, and sex, including True Story, the nation’s first “true confession” magazine. The Graphic burst on the scene with all the sweaty, hurling bravado of its founder. “We intend to interest you mightily,” announced its opening editorial. The paper would “flash . . . like a new comet” across the publishing landscape.11

Like the Daily News and the Mirror, the Graphic reveled in stories about deviance, torture, violence, and crime. But its sex was seamier, its scandal more scandalous, its crime more gruesome, and its claims more bogus than its tabloid rivals:

GIRLS NEED SEX LIFE FOR BEAUTY

WEED PARTIES IN SOLDIERS’ LOVE NEST

KIDNAPPED SCHOOLGIRL, 12, FEARED SLAIN BY FIEND

MY FRIENDS DRAGGED ME INTO THE GUTTER

Sunk into the depths of loneliness, Ann Luther, motion picture actress, is today in hiding in Hollywood. Since she lost her $1,000,000 suit against Jack White, wealthy motion picture producer, she has been, she says, “sick at heart.” Once trustful of her fellow beings . . . she has turned against the world in bitterness. Yet, in her breast burns the desire to have the truth set right before the world, and it is her story of tragedy and battle that she reveals today for the first time to GRAPHIC readers.12

Drawn in by the lurid headlines, readers stayed on for the Graphic’s regular features—its confessional fiction, prize contests, sports news, comic strips, and illustrations of women in various states of ecstasy and undress. Everything was written in Jazz Age slang: women were “shebas,” “red hot mammas,” or “broken butterflies.” When death or misery stalked a family, Graphic reporters and “picture hounds” were set on the trail. Parents were shown drooped over the limp body of a dead child; bandage-swathed victims were depicted scattered in the streets, writhing in pain. The Graphic’s front page was usually straddled by a bathing beauty whose “heaviest piece of raiment is the caption,” one critic quipped. Macfadden told his editors he wanted sex in each issue—“big gobs of it.”13

NOTHING BUT THE TRUTH, the Graphic’s motto, was often incanted but rarely followed. The Graphic did do some investigative journalism from time to time; a famous exposé of fraud in the Miss America Pageant led to the contest’s temporary closure in 1925. But a good deal of the Graphic was faked. When editors didn’t have a story, they made one up. If they didn’t have a photo to go with a story, they made that up, too. Photographs were cut apart and put back together; heads and bodies were superimposed and faces retouched. Perhaps the most infamous “composograph” came out of the 1925 trial of socialite Kip Rhinelander, seeking an annulment of his marriage on the ground that his wife hadn’t told him she was black. The wife was ordered to take off her clothes in court to show the color of her skin. A chorus girl posed in a reenactment of the scene, and the photo was retouched to look as if it had been taken on the spot. Editor and Publisher declared it the “most shocking news-picture ever produced by New York journalism.”14

The Graphic indeed “flashed like a comet.” It rose brilliantly, reaching a circulation of over two hundred thousand in 1926, but it flamed out after only eight years. Old-guard moralists saw the Graphic’s run-riot worldview as an assault on truth, privacy, and traditional values—“certain . . . to disrupt the home, ruin the morals of youth and precipitate a devastating wave of crime and perversion”—and the law came crashing down. New York authorities went after Macfadden for publishing a “lewd” newspaper, in violation of the state penal code. Over $12 million in libel suits were filed against the Graphic, making it the most sued publication in history to that time. Department store advertisers, the backbone of the New York dailies, had no interest in the “Porno-Graphic,” and Macfadden struggled to find advertising. While the Daily News and the Mirror continued to publish into the 1930s, the Graphic shut its doors in 1932 at a loss of $8 million.15

By that time, Harrison was long gone. He stayed at the Graphic for only eight months. What he did at the paper and why he left is shrouded in mystery. It was rumored that he left under less than honorable circumstances: according to Esquire, he was discharged “because he happened to introduce his immediate superior to a girl who gave him not only love but also the disease which is thought by some to be no worse than a bad cold.” It was “one of the few instances in . . . history . . . in which an employee was fired primarily because of the carelessness of the employer.”16

Harrison’s time at the Graphic left an impression on him. The paper’s outrageous ballyhoo spoke to him—it had a swagger and ballsy style that Harrison the street kid could relate to. The Graphic was Harrison’s journalism school, and it taught him the basics of publishing: how to paste up pages, edit copy, and write headlines. It also gave him his lifelong business philosophy: sex sells. From that point on, the idea of becoming a publi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Part I

- Part II

- Part III

- Part IV

- Notes

- Selected Bibliography

- Index