- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

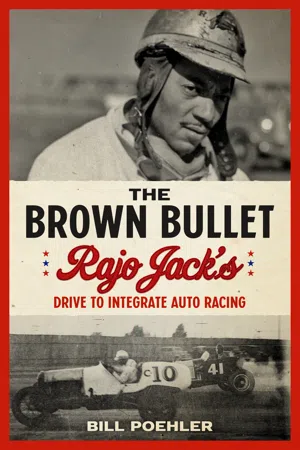

The powers-that-be in 1920s auto racing, namely the American Automobile Association's Contest Board, barred everyone who wasn't a white male from the sport. But Dewey Gatson, a black man who went by the name Rajo Jack, drove into the center of "outlaw" auto racing in California, refusing to let the pervasive racism of his day stop him from competing against entire fields of white drivers. In

The Brown Bullet, journalist Bill Poehler uncovers the life of a long-forgotten trailblazer and the great lengths he took to even get on the track, showing ultimately how Rajo Jack proved to a generation that a black man could compete with some of the greatest white drivers of his era, winning some of the biggest races of the day.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Brown Bullet by Bill Poehler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Longing for the Road

THERE WAS SOMETHING UNIQUE ABOUT the first-born child of Noah and Frances Gatson.

The skinny boy had a wide nose and dark hair like his father, but his complexion was light, so light many white people in the East Texas town of Tyler couldn’t tell what race he was. The black people of Tyler knew him as the son of Noah and Frances, the best-looking couple on their side of town. When Dewey Gatson was born in 1905, the area had been difficult for black people for the better part of a century and wasn’t improving.

When the Emancipation Proclamation took effect in most of the United States on January 1, 1863, the former slaves in Texas were not notified.1 They wouldn’t learn they were free until June 19, 1865. Abraham Lincoln’s executive order did little else to benefit former slaves. The largest industry in east Texas was farming, especially cotton, which was why the landowners brought the slaves in the first place. The land was almost exclusively owned by white men. Most of the former slaves were granted only their freedom and had few prospects for their future. For many of the formerly enslaved, their former masters gave them an option: live in the accommodations they already occupied and continue to farm the land. They could work a portion of the land with an option to purchase it after a few years. With no education and few skills, many of the former slaves agreed to the arrangement, though it was heavily weighted to the benefit of the white landowners.

The Gaston family rose to prominence before the Civil War by buying up large swaths of land previously thought unfarmable in East Texas and turning it into a booming agricultural operation.2 They made what seemed unattainable amounts of money off the backbreaking labor of their slaves on the plantations. The Gastons—French by origin, South Carolinians by emigration, and Texans by choice—were a well-to-do family before the Civil War. Robert Gaston moved his family and twenty slaves to Texas in 1849 and bought 320 acres along the Trinity River, followed soon by other branches of the family. Many of the slaves died along the way, but Robert prospered and served two terms in the Texas legislature. During the Civil War, many farmers in the area went broke as their family members went off to fight, but the Gastons prospered with their large workforce of slaves. After the Civil War, in which many Gaston men were killed or gravely injured, their farming operation continued to grow.

A young girl named Quilla was working as a domestic servant in the house of one of the Gaston families at a plantation outside Mount Enterprise in rural Rusk County, Texas. During the Civil War, she had been one of the family’s slaves.3 When she was freed, she stayed on in the same position, only this time for meager pay. One of the Gaston men—Quilla wouldn’t tell anyone who until much later—found the girl attractive.

When she found out she was pregnant, she dared not tell anyone. The other former slaves still working at the plantation said nothing; she was unmarried and feared what would happen should someone in the Gaston family learn the truth.

Noah Gatson—the Gaston family bestowed on their former slaves the bastardized last name Gatson as a courtesy—was born in 1877. Noah would never know his father, and his mother did not tell him his father was named Anderson until later in life. As Noah grew, people on the farm began to remark on the striking similarity between the light-skinned black boy and the Gaston men. The questions grew frequent, and Quilla opted to leave the farm to protect her child.

When Noah and his mother moved west from rural Rusk County to the town of Tyler—the seat of Smith County—there was a large and growing population of black people in the north part of town.4 In the late 1890s Tyler was booming, its population to 6,908 from 2,023 in the span of a decade. Tyler became the distribution hub for the massive amounts of cotton and other crops grown in the area.5 Bigger buildings appeared every year, and it quickly became a metropolis compared with the farming communities surrounding it. The roads of Tyler, however, were still dirt.

The city of Tyler was a departure from life on the farm for Noah and Quilla. Noah was seven years old when he first enrolled in school, a school specifically for black children. The benefit of moving to Tyler was more opportunities for black people to find work, but there wasn’t much diversity in the jobs available. Quilla found a job as a domestic worker for a wealthy white family, the best job for which she could hope, but the work was degrading.

Life in Tyler was still rough for black people. Every aspect of the town was segregated. Vast swaths of property on the south side of town were owned by white people, and large numbers of stately houses were constructed there. The north side became home to the black population and was made up of poorly constructed, high-density housing. Noah Gatson dropped out of the “coloreds only” school in Tyler at age twelve and found work in what odd jobs he could find. He cleaned horse stables and worked as a janitor. When Noah was fifteen, Quilla suddenly grew ill and died. She had been religious and took her son to church, but when she died, he stopped going.

Noah had first met Mattie Anderson at church, however. She was short and had a darker complexion than him.6 She was older and exotic to young Noah. In 1894, seventeen-year-old Noah and twenty-two-year-old Mattie married in what everyone referred to as Tyler’s “colored” Baptist church, the Jackson Spring Hill Baptist Church. They rented a room in a building at 1103 West Ferguson Street and made it home.

The building was technically on the white side of town—and in the same block as the all-white Oakwood Cemetery—but was so derelict and close to the town’s unofficial racial border of the railroad tracks that black people were allowed to occupy it. Though at the time the Ku Klux Klan was dissipating in the area and its influence was waning, racial tensions hadn’t improved since the Civil War: black men were lynched in Tyler in 1897 and 1898.7

Noah wanted to start a family immediately; Mattie couldn’t conceive a child. Mattie found work as a housekeeper. Noah sought a job where he could make more money than he could earn as a menial laborer.

Tyler was the main hub of the St. Louis Southwest Railroad, known as the “Cotton Belt Railroad,” with its general office, round houses, and machine shop in its depot on the north side of town.8 Its business of moving goods to Arkansas, Tennessee, and Louisiana boomed with the growth of agriculture in Smith County in the 1890s. Many industries in town excluded black workers, but railroads were an exception. Top jobs like conductor went to white men, but jobs were available to black men, especially ones with light skin. On passenger trains, light-skin black men could find work as porters or mechanics. When it came to the freight trains moored in Tyler, there was constant need for men to work.

Through friends, Noah Gatson learned of the lucrative jobs on the railroad. He had no technical skills but showed up at the railroad’s shop every day until he was finally given a job sweeping floors. He progressed to machinist assistant and eventually to machinist. With his lofty and lucrative position, Noah became the envy of many. Most jobs in the area for black people at the time involved growing and picking cotton, something he despised. And the perk was Noah could ride the railroad.

Mattie’s job with a prominent white family often took her on trips far from home. In late 1903, she joined the family for a trip south to the state capital of Austin.9 On January 5, 1904, Mattie was admitted, barely conscious, to the black hospital in Austin and died of exhaustion. Noah was devastated.

The funeral for Mattie at the Baptist church in Tyler lasted days. The women of the town looked after the handsome twenty-six-year-old widower, bringing him food and caring for him while he grieved. It wasn’t long before they introduced him to eligible women in town. The black community wasn’t large, so he thought he already knew all the available women. Noah begged off invitations, but it didn’t stop the women from trying.

One woman caught Noah’s eye. Her name was Frances Scott, and she was striking.10 Frances was born in the rural Texas town of Lampasas to Mimi Scott in 1888. Like Noah, she never knew her father, also a white man. Frances had a similar fair complexion as Noah and came from similar heritage. Frances was sixteen years old and new to town when she first met Noah, and he was an intriguing twenty-seven years old. He had a good job, was handsome, and seemed to live a good life. On September 28, 1904, ten months after his first wife died, Noah Gatson married Frances Scott.

Ten months later, on July 28, 1905, Dewey Gatson was born.11 It would be another fifteen years before he would become Rajo Jack.

Born in the family’s apartment in the derelict two-story building on Ferguson Street in Tyler, Dewey was a tall child. As soon as he could walk, he was a tornado of motion and a challenge for anyone to keep up with. Dewey was affectionate with his mother; Noah Gatson didn’t return his son’s affection. Noah had always been a casual drinker, but he drank more and started smoking cigars while working long days for the railroad.

Noah’s lofty position with the railroad paid well—so well Frances wouldn’t have to work and could take care of her new son, a rarity in the black community. Frances took after her mother by keeping chickens in a coop outside their rented building, as much for something to do as for the food. Having money gave the Gatson family comfort, but it didn’t buy them acceptance.

In the summer of 1907, the Ringling Brothers Circus came to Tyler and set up downtown, a short walk from the Gatson family home.12 For the people of Tyler, it was the event of a lifetime. There was a plethora of attractions, many off limits to black people like the Gatson family. The attraction Noah wanted to see most was a car, an attraction open to everyone. It wasn’t much compared to most of the cars of the day, but it was the first car to come to Tyler. Though Noah was mechanically inclined and spent long days working on train engines, this was amazing. When the car’s engine stumbled to life, it gave off a great roar. Some of the crowd backed away due to the noise and smoke. But two-year-old Dewey was fascinated and went in for a closer look. He desperately wanted to climb into the car, but Noah was left to explain why a black person couldn’t get in a white man’s car.

On August 18, 1907, Lindsey Gatson was born, giving Dewey a little brother. Another brother, Sydney, was born in 1908, but died days later. Frances was crushed.

Frances Gatson was religious and read the Bible to her sons daily. Every Sunday, Frances would gather her children—but not Noah—to attend church. When he was sober, Noah was a hard-working, diligent man, but those times were becoming rare.

In 1909 Jim Hodge of Tyler—a black man the Gastons knew in passing—was accused by a white woman of rape.13 He was arrested and taken to the Smith County Jail in downtown Tyler. A mob of white men wanted justice and weren’t willing to wait for the court to decide his fate. The men gathered sledgehammers, broke down the door to the jail, stole Hodge out of his cell, and lynched him at the site where the new courthouse was under construction. The white woman later gave statements that made people believe Hodge was innocent, but he was already dead. It sent ripples through the black community. There was still a small presence of Ku Klux Klan in the area, but this wasn’t its doing. Average white people in the community had done it.

Dewey Gatson was a five-year-old boy who wanted only to play with his new sibling in the dirt outside their house and hear Bible stories read by his mother when a series of events that would shape the course of his life took place.

A fellow Texan, Galveston-born Jack Johnson—the child of former slaves who grew up a frail boy—rose to prominence in the boxing world.14 During an apprenticeship with a painter and boxing fan, Johnson first tried the sport and showed an aptitude almost immediately. His ascension in that world was astounding. In February of 1903, Johnson defeated Ed Martin to win the World Colored Heavyweight Championship.

Johnson hungered for a shot at the World Heavyweight Championship, a realm reserved exclusively for white fighters. Jim Jeffries, a white man from Ohio, won the World Heavyweight Championship in 1899, but he avoided Johnson at every turn and eventually retired in 1905.

When Johnson knocked out former World Heavyweight Champion Bob Fitzsimmons in 1907, he was finally considered a contender for the title. World Heavyweight Champion Tommy Burns agreed to fight Johnson for the championship on December 26, 1908. After fourteen rounds, police stopped the fight and Johnson was declared the winner, making him the first black man to hold the belt. It was the first time a black athlete had proven himself greater than a white man at such an athletic pursuit. In response, Jeffries came out of retirement in 1910 to fight Johnson in an eagerly anticipated July 4 bout in Reno, Nevada. The press dubbed Jeffries “The Great White Hope.”

“I am going into this fight for the sole purpose of proving that a white man is better than a negro,” Jeffries said.

Billed as the “Fight of the Century,” the match ended when Johnson won by technical knockout after fifteen rounds. And he earned a fortune of $60,000. Around the United States, race riots broke out in New York, Pennsylvania, Georgia, and Texas after the fight. At least twenty people died in the riots.

The anger white people felt wasn’t just about a black man defeating a white man in the boxing ring, but also the brash manner with which Johnson presented himself. He wore fur coats and dated—and eventually married—white women. Transporting white women across state lines was a violation of the Mann Act and would land him in prison later in life. Johnson was unapologetic in how he carried himself, especially to the press. Outside the ring, Johnson spent money on whatever caught his fancy, and the newest and fastest cars were among his splurges. In his grand motor cars, Johnson sp...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: The Unlikely Hero

- 1 Longing for the Road

- 2 Becoming Rajo Jack

- 3 Taking a Step Back to Move Forward

- 4 The Outlaw Emerges

- 5 The Rise to Prominence

- 6 The Folly of Negro League Midget Racing

- 7 From Obscurity to National Champion

- 8 Independence and Reaching a New Height

- 9 Lucky Charms Fail to Deliver

- 10 The Super-Sub Wins the Other 500

- 11 The Big Crash and Road to Obscurity

- 12 Racing Around the Fringes

- 13 Rising from the Ashes

- 14 The Indy 500 Dream

- 15 Hawaiian Interlude

- 16 A New Dream

- Epilogue: Rajo Jack as a Work of Art

- Rajo Jack's Wins

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index