![]()

1

The Origins of Doping and Anti-Doping in Modern Sport

Sport as we now recognize it came into being during the late nineteenth century. Of course, there had been various forms of physical competition in a variety of cultures and civilizations before then. Some carried religious significance, or were associated with local holidays, while others were part of royal celebrations. There were also highly organized and competitive sporting events, such as the ancient Olympic Games. Some sports evolved from traditional games, while others are recent inventions. One change that had implications for doping, and later for anti-doping, was the idea of sport as a profession. Sport as a paid career rather than a vocation or hobby was not common or widely accepted until quite recently and has led to the development of new ways of thinking about and doing sport. Gaining celebrity and monetary rewards for sporting success was not new, but these shifts in sporting culture would have a dramatic effect in the twentieth century.

Britain became the crucible of world sport during the period of rapid urbanization and industrialization in the mid- to late nineteenth century. The shift from an agrarian economy to one focused around factories within towns and cities meant that time and space became highly structured. The notion of ‘leisure’ time spread among different social groups in these years. Clear boundaries between working and non-working hours impacted both the ways people organized their time and what was made available to them when off the clock. This differentiated work from play and opened up the consumer leisure industry.

Sports clubs became a new, popular part of British culture. Some developed to encourage participation and recreational sport. However, other clubs emerged with a competitive focus. Some of these elite clubs selected the best players to represent them and their community. This was helped along by new technologies that allowed for easier, quicker travel. The introduction of the rail system meant that teams could be formed and regularly play each other in leagues. In order to avoid conflicts over local rules, sports needed some common, formalized guidelines so that competitions would be controlled and fair. In turn, those rules needed governing bodies to ensure that the clubs followed them. Governing bodies undertook the standardization of how sports would be contested and officials were trained to ensure these policies were correctly implemented. By the 1870s and ’80s, national tournaments and leagues had emerged and many more clubs were formed in a range of sports.1

Other countries were not far behind. The British Empire provided fertile ground for spreading these new rules and competition formats far beyond Britain and even continental Europe. The imperial diffusion of sport was driven by working-class soldiers and labourers who took their games abroad as pastimes when dispatched for long stretches. Equally important were colonial officers, teachers and religious leaders who used sport to discipline colonial subjects. The lessons of self-discipline, following orders and the gentlemanly handshake after the game were all considered important parts of British culture that should be instilled in the colonies. Sport provided a vehicle for teaching other values and lessons as well. Missionaries trying to Christianize and ‘civilize’ the locals also used sport within their schools and churches. The idealism of the English public-school system was combined with the Victorian theory of rational recreation to promote organized sports at home and abroad.

Of course, there were differences of class, gender and cultural identity inherently wrapped up in sporting cultures. The middle and upper classes played cricket, rugby and hockey; the lower classes played football and boxed. Clubs were often exclusionary: rules against membership for women, ‘natives’ and (working-class) professionals were common. Sport brought communities together in shared activities, but could also define, separate and distinguish groups within those communities as necessary.2

A commercial impetus sat alongside these amateur and moralistic endeavours. Many entrepreneurs seized the opportunity presented by this new appetite for mass entertainment. Club owners could charge entrance fees by restricting access to matches. Popular sports were covered in the media, which allowed for additional revenue streams by selling sponsorships and advertising. Team sports like football found huge pools of support due to their identification with specific towns and communities. These were often associated with specific factories or businesses that would give the workers a half-day off on Saturdays to watch their team play. This drove loyalty and interest, as well as provided opportunities for spending money. Local and national rivalries stoked interest in these matches and players soon became celebrities.

By the end of the century, sport saw the rise of a new type of sportsman: the professional athlete. Professionalism was rapidly accepted in sports such as football and cycling. Others were not so quick. Rugby league allowed players to be paid while rugby union did not (it was not until the early 1990s that rugby union was professionalized). There were other issues and implications of professionalism that some sports struggled to sort out. Prize money for athletics races became a source of tension between the traditionalists who wanted to keep athletics amateur and the progressives who felt athletes should be able to earn a living from their sporting labours. Many sports, not least horse racing, attracted gambling, leading to suspicions of race and match fixing. The rapid development of rules in a number of sports was intended partly to protect the fairness of competition for the athletes and teams, but also to protect bookmakers and gamblers from unfair practices on and off the field. The fledgling sports industry needed transparent rules and regulations.3

Indicative of the global scale and scope of this new sporting culture was the founding of the International Olympic Committee, formed in 1894, and the staging of the first modern Olympic Games in 1896 in Athens. The effort to hold a global multi-sport event was led by Baron Pierre de Coubertin, whose speeches and writings often referred to the lofty ideal of friendly competition. He was inspired by the English public-school approach to sport in the mid-nineteenth century. Central to this vision was amateurism: the strict rule that no athlete should get paid. Underpinning this idea was the belief that sport had a purity and nobility that would be lost, indeed corrupted, if money was changing hands. There was, of course, some class snobbery here. Competing in sport at a high level was time-consuming and expensive, especially when factoring in travel and time spent away from paid work. Wealthy people could afford to do sport purely for leisure, but less privileged athletes needed to earn money.

Some sports institutionalized this class division. Cricket had a clear distinction between Gentlemen and Players, which included the use of changing areas and pavilion spaces and the contributions they made to the team. The Olympics was designed for amateurs, meaning athletes had to be wealthy to participate, not least because the events took place in various countries and lasted several weeks. The 1981 Oscar-winning film Chariots of Fire epitomized this division. The film focused on the 1924 Olympic Games in Paris. Almost all the competitors were middle or upper class, including some who were students at Cambridge University. Events like these were the exclusive domain of those who could afford not to work. Money, rather than talent, likely decided many Olympic outcomes.

It is worthwhile to note that one of the main characters in Chariots of Fire was based on Lord Burghley, who would be at the forefront of the IOC’S first official decree against the use of drugs in sport in 1938. A less prominent character was New Zealander Arthur Porritt. Porritt eventually moved to England, became a royal physician and was tasked with leading the IOC’S first Medical Commission in 1961. The Commission’s remit included developing anti-doping rules and testing.

Early Experiments

The earliest documented examples of early drug use in high-level sport are from the 1904 and 1908 Olympic Games, and both involved strychnine and marathon runners. There had been one major case of alleged drug use before then: the death of cyclist Arthur Linton in 1896. His death has been widely attributed to doping. A Welsh champion, Linton often competed in the major European races. His coach, James Edward ‘Choppy’ Warburton, had a reputation for giving his riders a secret concoction to drink. When Linton died after the Bordeaux–Paris race, it seemed plausible that stimulant drugs were at least partly to blame. This myth was repeated in a broad range of publications throughout the twentieth century. Linton’s actual death, however, was far less dramatic, though no less tragic. His Times obituary indicated that the talented cyclist died several weeks after the race from typhoid.4 The repetition of his alleged death-by-doping tragedy demonstrates how drug use captured the imagination of many writers: the idea that someone would take such high risks and suffer such serious consequences for sporting success contains all the ingredients for a captivating drama.

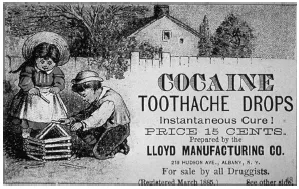

There are other relatively innocuous examples of runners and cyclists using stimulants around the time of Linton’s death. Cocaine had become widely available and was rumoured to be popular among long-distance cyclists. The marketing of coca (from leaves) and cola (from nuts) in tonic drinks led to the creation of Coca-Cola, while cocaine was widely sold in drinks, pills and powders for use as pain relievers and ‘pep pills’. Far from pushing the boundaries of enhancement, athletes were simply following trends. Scientists had been showing the value of these substances since the 1870s. One of the earliest experiments on coca leaves took place in Edinburgh in 1870 and 1875, led by Sir Robert Christison, professor of medicine at the University of Edinburgh, Ordinary Physician to the Queen in Scotland and president of the British Medical Association. He used his first batch in 1870 to assess the effects on two students who walked 16 miles with no stimulant. When they returned in a state of exhaustion, he gave each a small amount of coca, which re-energized them enough to continue walking for another hour. Five years later, Christison experimented on himself on three occasions: twice on local walks, and once while hiking the 985-metre Ben Vorlich mountain in Scotland. He was 78 years old at the time. He reported feeling less tired when he took the coca towards the end of the first walk of 15 miles. For the mountain hike, he used the drug only towards the end of the ascent, around 100 metres from the summit. In fact, he was full of praise for the effects and the lack of side effects. Reflecting on the hillwalking experience in the British Medical Journal, he wrote: ‘I at once felt that all fatigue was gone, and I went down the long descent with an ease like that which I used to enjoy in my mountainous rambles in my youth.’ He felt ‘neither weary, nor hungry, nor thirsty, and felt as if I could easily walk home four miles’.5

Arthur Linton, falsely accused of being the first doping death.

Sir Robert Christison, who conducted experiments on coca leaves in the 1870s.

Sigmund Freud wrote about coca in 1884, based on his own use and accounts he had heard from other users. He ‘professed optimism about its potential to counteract nervous debility, indigestion, cachexia, morphine addiction, alcoholism, high-altitude asthma, and impotence’.6 Coca was seen as having the potential to cure a range of ills rather than being the cause of them. By the early twentieth century cocaine was widely consumed. Of course, this was before its addictive properties were generally known. Historians George Andrews and David Solomon described the situation in America:

Anybody could saunter into a drug store and buy cocaine in a variety of forms. Indeed, it appeared in so many guises that the druggist might well have asked the customer whether it was wanted to be sniffed as a powder, nibbled as a bonbon, sucked as a lozenge, smoked as a coca-leaf cigarette, rubbed on the skin as an ointment, used as a painkilling gargle, inserted into bodily cavities as a suppository, or drunk as a thirst-quenching beverage such as Coca-Cola.7

Other substances were equally attractive to early researchers of performance enhancement. Scientists in several countries researched the effects of food, vitamins, drinks and stimulant drugs on sport performance in various contexts. For example, in the late nineteenth century the leading French scientist Philippe Tissié used an elite cyclist to study the properties of potentially stimulating drinks. Also in France, the psychologist Gustave Le Bon was interested in discovering the effects of the kola nut. Le Bon experimented on a leading cyclist, concluding that the nut was a ‘powerful resource’. Before long, kola as well as coca garnered much interest from scientists and manufacturers of tonics, medicines and supplements. Both were new to North America and Europe after being imported from South America.

The 1904 Olympic Games were held in St Louis in the United States. As usual, the marathon race was one of the main attractions. The event ended up being overshadowed by scandal after attempts by American Fred Lorz to cheat his way to success by being driven in a car for part of the route. His disqualification meant that his rival, Thomas Hicks, won the race. In those days the marathon was a rather brutal affair and the 1904 race was no exception. Runners had support staff in cars and ran in very unforgiving footwear. The summer heat in St Louis meant that temperatures were over 32°C (90°F). There was only one water station on the course, as the science of hydration was newly emergent. Of the 32 runners who started, only fourteen finished. Hicks suffered greatly for his win. In order to get him across the finish line, Hicks was dosed with strychnine mixed with brandy during the race. Late twentieth-century descriptions suggest that he collapsed at the finish and nearly died, likely because of the strychnine. Whether because of this or the unforgiving conditions, Hicks was in poor shape following the marathon.

Example of the everyday use of cocaine in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

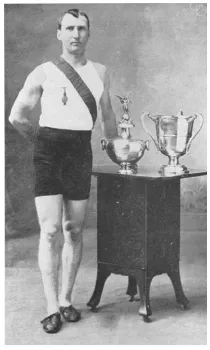

Thomas Hicks, winner of the 1904 Olympic marathon, with the winner’s trophy.

As with the Linton story, a near-suicide-for-gold-medals story is so attractive to writers that many have failed to consult the historical evidence or examine the broader social context. At the time, strychnine was not strictly considered a poison and scientists investigated its stimulant properties alongside its risks. For example, scientific research presented to the Royal College of Physicians in 1906 concluded that strychnine reduced fatigue. More specifically, a paper in the Journal of Physiology in 1908 showed that a few milligrams given orally produced ‘an increase in the capacity for muscular work’ which peaked between thirty minutes and three hours after ingestion, according to the dose, and thereafter capacity became subnormal. Doctors lauded strychnine for its medical properties in this era. The medical historian John S. Haller Jr wrote that by the end of the nineteenth century the drug had become ‘one o...