- 202 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Routledge Introduction to American Drama

About this book

This volume provides an accessible and engaging guide to the study of American dramatic literature. Designed to support students in reading, discussing, and writing about commonly assigned American plays, this text offers timely resources to think critically and originally about key moments on the American stage.

Combining comprehensive coverage of the core plays from the post-Revolutionary era to the present, each chapter includes:

- historical and cultural context of each of the plays and their distinctive literary features

- clear introductions to the ongoing critical debates they have provoked

- collaborative prompts for classroom or online discussion

- annotated bibliographies for further research

With its accessible prose style and clear structure, this introduction spotlights specific plays while encouraging students to contemplate timely questions of American identity across its selected span of US theatrical history.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Routledge Introduction to American Drama by Paul Thifault in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Contrast (1787) by Royall Tyler

DOI: 10.4324/9781003142713-1

I Text and Context

Royall Tyler’s (1757–1826) The Contrast was the first comedy written by a US citizen to be performed professionally in the new nation. It is arguably the first successful work of American drama both in terms of its popularity with original audiences and its lasting critical appeal. It remains a hallmark of early US dramatic literature that continues to receive scholarly attention. The Contrast is also an early example of US literary nationalism that foregrounds its patriotic message and calls attention to itself as a marker of American cultural progress. It has an overarching concern with “contrasting” fashionable European immorality with American virtue. In doing so, it is known for giving life to the stock character of the Yankee country bumpkin, a good-hearted but comically inept figure whose rural manners and dialect would reappear to delight audiences in dozens of US plays in the years ahead.

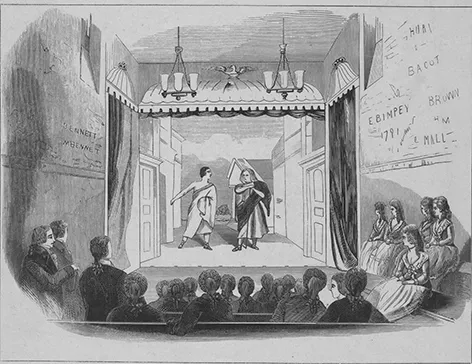

After a much-applauded 1787 debut in New York, The Contrast moved up and down the Eastern Seaboard with performances in virtually every major city in the early republic. Its geographical footprint is surprising in light of widespread early American prejudice against drama. As Lucy Rinehart points out, at the time theatrical performances were fully lawful only in the states of New York and Maryland (32). To be performed in Boston, where its humor and style seem to have won over New England’s ongoing Puritanical suspicion of the theatre, the play had to be billed as a “moral lecture,” and in Philadelphia it was publicly read aloud rather than performed (Frick 2). For a play of its time, it also had an unusually large presence in literary culture, being read widely in book format (Quinn 65), being the first American play to be reviewed by the press (Vaughn 24), and being the first dramatic work to enter US copyright (Rinehart 34). It also had a profound influence on American literary history, most notably inspiring William Dunlap, “the father of American drama,” to begin writing plays.

Figure 1.1 An interior view of the John-Street Theatre in 1791, where The Contrast premiered a few years earlier.

Source: From The New York Public Library, https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5e66b3e8-bbe9-d471-e040-e00a180654d7.

In addition to penning a number of important works of early US literature (including the 1797 novel The Algerine Captive), Royall Tyler was connected to significant early US institutions, historical events, and political figures. Born in Boston in 1757 to a prosperous merchant family, Tyler attended both Harvard and Yale, fought in the Revolutionary War, and was at one point engaged to the daughter of John and Abigail Adams (when she broke it off, Tyler was devastated). Like many early American authors, he did not rely on writing for his income. Rather, Tyler enjoyed a successful legal career, eventually becoming Chief Justice of Vermont’s Supreme Court and a law professor at the University of Vermont. Tyler’s participation in major historical events shaped The Contrast. For instance, he wrote the play shortly after serving in a militia that helped put down Shays’ Rebellion, an armed revolt of Western Massachusetts farmers, many of them veterans of the Revolution, who rose up in response to a debt crisis and mounting taxes. Though opposed to the rebel cause, Tyler understood the plight of the rural populace and may have even written The Contrast as an attempt to regain a sense of national harmony.

Tyler’s enduring fame rests squarely on the success and lasting appeal of The Contrast, a five-act comedy set in post-Revolutionary New York City. The light-hearted plot centers on two families, their servants, and their attempts to navigate a series of romantic entanglements in which love wins out over lust, greed, and duplicity. Written in under a month, the play is openly modelled on Richard Sheridan’s (1751–1816) British comedy The School for Scandal (1777), with characters in The Contrast even attending at one point a performance of Sheridan’s play. Tyler pays homage to British models while attempting to Americanize the subject matter. The play’s complex relationship to previous British plays owes to the precarity of American arts in the early republic. Writers of the period contended with a sense of American cultural inferiority to Europe. The Contrast can thus be read as trying to elevate American life by exposing how the so-called superiority of European culture rested on decadence and immorality. Yet what rescues The Contrast from being either a pure imitation of British models or a pro-American repudiation of all things European is the fun it pokes at all parties. The Europhile characters are held up as duplicitous, the righteous Americans can appear as tiresome bores, and the rural Yankee is the butt of many jokes. With the significant exception of the play’s villain, Billy Dimple, the representatives of all of these types reunite in the play’s patriotic conclusion.

Another distinct aspect of The Contrast is its use of social comedy to celebrate American nationhood. This aim is established in the opening lines of the prologue: “EXULT, each patriot heart!—this night is shewn / A piece, which we may fairly call our own; / Where the proud titles of ‘My Lord! Your Grace!’ / To humble Mr. and plain Sir give place” (Tyler 7). The Contrast tends to align matters of taste, decorum, and speech with central ideas about what constitutes Americanness. When the play begins, we are introduced to young American characters who, though charming, blindly imitate European manners, which Tyler represents as a preference for fashion over practicality, showiness over substance, and guile over honesty. The witty Charlotte tells of how, in full view of “a knot of young fellows,” she takes a purposeful “false step” so that she might reveal a scandalous glimpse of her shoe underneath her bell-hoop dress (9). Such flirtation, she says, is a far better way to woo the opposite sex than earnestness and forthrightness. Though revealed humorously, Charlotte and Letitia’s flirtation and gossip garner a sinister quality by their association with a larger dishonesty. Both women believe they are on the verge of stealing the young Anglophile Billy Dimple away from his fiancé, the honest and moral Maria, whom Charlotte repeatedly mocks as being a prudish woman of “sentiment.” Dimple, we soon learn, is a rake who seeks to trick Maria into dumping him so that he can seduce the beautiful Charlotte with no intention of marriage, and marry Letitia solely for her money.

Charlotte’s wit and materialism are offset by her virtuous brother, the Revolutionary War veteran Colonel Manly, who models humility, frugality, and honesty. Notably, he arrives in New York on an errand that combines all these qualities: he has come to help secure pensions owed to wounded American soldiers. In Manly’s first appearance, ideas about fashion become entangled with loftier ideas about democracy. After Charlotte insists that Manly see a tailor for some new clothes, he lauds the respectability of the military coat that saw him through the war. He then goes on to criticize American taste for European fashion in peculiarly political terms:

I have often lamented the advantage which the French have over us in that particular [in matters of fashion]. In Paris, the fashions have their dawnings, their routine, and declensions, and depend as much upon the caprice of the day as in other countries; but there every lady assumes a right to deviate from the general ton, as far as will be of advantage to her own appearance. In America, the cry is, what is the fashion? and we follow it, indiscriminately, because it is so.

(23–24)

Such speeches capture the subtlety of The Contrast, wherein oppositions (“contrasts”) between “America” and “Europe” are more nuanced than they first appear. We might expect the patriotic, soldierly Manly to spurn all fashion as mere superficiality. Instead, he recognizes the value of fashion insofar as individuals are free to “deviate” to suit their own bodies, as in France. The problem in America, he implies, is not trying to look one’s best but a decidedly undemocratic adherence to whatever is decreed fashionable abroad. This critiquing of Americans who ascribe to rules set by others recurs throughout the play in multiple registers, in Dimple’s disastrous fidelity to the writings of Chesterfield, and in Jonathan’s hapless attempts to follow courtship rules he does not understand.

Inscribed in such a theme, perhaps, is Tyler’s own preemptive stand against those who would criticize his play for deviating from theatrical or literary tastes set by Europe. Such a reading seems even more plausible if we recognize how deeply the play’s conflicts involve literature and theatre. By reading sentimental novels, Maria Van Rough comes to long for true love over what her greedy Yankee father calls “the main chance” of financial stability. Meanwhile, her rakish fiancé Dimple adheres to the writings of the British Lord Chesterfield for guidance on fashionable, self-serving immorality. In addition to prose writings, drama itself is glimpsed in the play. Jonathan’s rural backwardness is most memorably captured in his failure to recognize that he is at a live performance of a play (he thinks he’s sitting in a church and looking in on a nearby home) while Jessamy’s European decadence is spotlighted in his absurdly structured etiquette for behaving at the theater. In an extended metaphor, Charlotte describes socializing itself as a kind of play, detailing the successive workings of social gatherings, from beginning to end, as a series of dramatic movements from the rise to the fall of the “curtain” (23). All of these literary and theatrical allusions and conflicts make The Contrast for the period an especially self-conscious work of art, one that meditates on the nature of literature and drama at a time when many in the United States still saw imaginative writing as a potentially corrupting force.

If The Contrast defines mainstream American identity against a fidelity to European models, the play also offers us the chance (perhaps unintentionally) to consider the experiences of marginalized people in the early republic. The play’s two most explicit references to race seem indicative of how African Americans in early US literature often serve merely as foils for revealing things about white characters. After spreading gossip about the alleged engagement of a friend to a wealthy Southerner, Charlotte is asked to reveal her source. The information, she claims, came to her via her “aunt Wyerley’s Hannah” who “though a black … is a wench that was never caught in a lie in her life” (12). Charlotte then supplies a convoluted list of people through whom Hannah attained her information. Whether the servant Hannah is enslaved or free is undetermined, but her race and associated low status are crucial to the intended joke—that Charlotte is a gossip whose information is far from reliable. More explicitly, Jonathan, the character who will inaugurate the tradition of the stage “Yankee,” is literally defined in opposition to African American identity. In his first appearance in the play, Jonathan takes offence when referred to as Manly’s servant: “Servant! Sir, do you take me for a neger,—I am Colonel Manly’s waiter” (25). Jonathan jealously sees his own rather low social position as clearly above that of an enslaved Black person, and hence we see racism serving as the very basis of Jonathan’s comically inflated self-image, not to mention the source of his first intended laugh in the play. It would be going too far to say the play here endorses Jonathan’s sense of racial hierarchy, given his comic cluelessness. The issue of racial inequality is invoked but not in any serious way engaged, which is itself worth examining.

Though the play’s democratic ethos does not seem to extend to racial minorities, some moments may be said to resist the patriarchal culture of the early United States. Maria’s speeches often reveal a proto-feminist aspect. Maria’s first appearance finds her “disconsolate at a Table, with Books, etc.” (13), where she soliloquizes on the common cultural stereotype that women love a man in uniform, and the tendency for women to be mocked for such an attraction. Maria reasons that it makes sense for women to seek men whose apparel suggests “generosity and courage,” for women live in a precarious world of traps and temptations, often set up by men, in which “the smallest deviation from the path of rectitude is followed by contempt and insult.” Women, she says, are prisoners of “reputation” but are denied the “masculine” opportunity to defend themselves in the way men can (14–15). Though it hardly seems progressive today for a woman to declare the need for a strong man, Maria’s speech manages to make that argument an occasion for exposing gender inequality and double-standards.

II Critical Conversations

Critical conversation surrounding The Contrast tends to center on three issues: the play’s composition and influences, the potential political contradictions in its satirical depiction of its heroes, and its revelatory portrait of early US urban life. In terms of the play’s composition, scholars often note the unlikely circumstances under which Tyler wrote his first play. Growing up in Puritanical Massachusetts where dramatic performances where banned until the 1790s, Tyler would have seen precious little live theatre. For scholars, this apparent dearth of exposure to drama is difficult to square with the literary and dramatic expertise on display in The Contrast. Coupled with the fact that...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- 1. The Contrast (1787) by Royall Tyler

- 2. André (1798) by William Dunlap

- 3. The Indian Princess (1808) by James Nelson Barker

- 4. Fashion; Or, Life in New York (1845) by Anna Cora Mowatt

- 5. The Octoroon; or, Life in Louisiana (1859) by Dion Boucicault

- 6. Margaret Fleming (1890) by James A. Herne

- 7. Trifles (1916) by Susan Glaspell

- 8. The Children’s Hour (1934) by Lillian Hellman

- 9. Our Town (1938) by Thornton Wilder

- 10. A Streetcar Named Desire (1947) by Tennessee Williams

- 11. Death of a Salesman (1949) by Arthur Miller

- 12. Long Day’s Journey Into Night (1956) by Eugene O’Neill

- 13. A Raisin in the Sun (1959) by Lorraine Hansberry

- 14. Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (1962) by Edward Albee

- 15. Funnyhouse of a Negro (1964) by Adrienne Kennedy

- 16. Fences (1985) by August Wilson

- 17. Angels in America: A Gay Fantasia on National Themes (1993–94) by Tony Kushner

- 18. Sisters Matsumoto (1998) by Philip Kan Gotanda

- 19. Topdog/Underdog (2001) by Suzan-Lori Parks

- 20. Water by the Spoonful (2012) by Quiara Alegría Hudes

- 21. An Octoroon (2014) by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins

- Index