eBook - ePub

The Global Future of Higher Education and the Academic Profession

The BRICs and the United States

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Global Future of Higher Education and the Academic Profession

The BRICs and the United States

About this book

This is the first book to critically analyze the future of higher education systems in the four BRIC countries - Brazil, Russia, India and China - and the USA, analyzing academic salaries, contracts and working conditions and how national policy will affect the academic profession in each context.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Global Future of Higher Education and the Academic Profession by P. Altbach, G. Androushchak, Y. Kuzminov, M. Yudkevich, L. Reisberg, P. Altbach,G. Androushchak,Y. Kuzminov,M. Yudkevich,L. Reisberg in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Prospects for the BRICs: The New Academic Superpowers?

Philip G. Altbach

The BRIC countries—Brazil, Russia, India, and China—are expanding rapidly, and many observers see these countries as dominant economies in the coming decades. When economist Jim O’Neill coined the term BRIC in 2001, those countries accounted for 8 per cent of global gross domestic product (GDP). He predicted that this would increase to 14 per cent by 2011. In fact, the BRICs accounted for almost 20 per cent of GDP in 2012 (Liu and Li 2012). Fareed Zakaria, among others, has commented on a major shift in global influence away from North America and western Europe, and the BRICs are seen at the forefront of this shift (Zakaria 2008). Logic might dictate that academic power will rise along with economic and political expansion (Levin 2010). These four countries do indeed show impressive growth in their higher education systems and promise to expand and improve in the coming decades. Yet, it is by no means assured that the BRICs will achieve the academic prominence that is likely in economic or political spheres. Each, as will be discussed here, faces significant challenges. Some of the systemic factors that impact higher education in the BRICs are analyzed in this chapter; this is followed by an analysis of the most central prerequisite for academic development and excellence—the academic profession.

If the economic destiny of the BRICs is on an upward trajectory, the same cannot be said with certainty for higher education. Just as there are significant variations in the details of economic and political development among the four BRICs, quite different academic traditions, current realities, future plans, and scenarios make it likely that the four countries will proceed along quite different academic paths. Further, the route to global academic dominance is highly complex and depends on much more than patterns of economic growth or the sophistication of a nation’s economy or society.

All four BRICs are, in different ways, transitional academic systems. Three—Brazil, China, and India—face the challenge of rapid expansion of access and enrollments; at the same time they are attempting to build world-class research universities at the top of the system, to contribute research and top-level training to an increasingly sophisticated economy. Russia, which possesses a mature higher education system and offers a high level of access, faces the challenge of rebuilding its research universities, while improving the quality of the system as a whole.

Centers and peripheries

The BRIC countries find themselves in an unusual paradox. On the one hand, none of them are yet an academic superpower. All lag behind the main academic centers. On the other hand, all except Russia have rapidly expanding academic systems and goals of improving their global standing and building top-ranking universities. Further, all four BRICs are significant regional centers, influencing neighboring countries, and providing academic leadership in their respective areas. Brazil, India, and Russia are by far the most productive academic systems in their regions. In East Asia, Japan remains the dominant academic power, and South Korea is expanding academically, but China has the fastest growth rate and is investing the most resources in higher education.

Russia remains the central academic influence in the former Soviet Union, and Russian is the main language of instruction and research as well. Although countries in Eastern Europe are increasingly looking toward the West and English is replacing Russian a key language of academic communication, Russia retains some influence. India is by far the largest and most influential academic system in south Asia, with some modest impact in the Middle East as well. Brazil is the scientific superpower in Latin America, in terms of research productivity, the production of doctorates, and to other areas. The fact that it uses Portuguese and the other countries are Spanish-speaking limits its influence, however.

Each of the BRICs, because they contain large and self-sustaining academic systems, see themselves as independent academic entities. At the same time, they look to the major academic powers for ideas about higher education development, research paradigms, and other matters. China and Russia are to some extent adapting Western academic organizational and governance ideas. Brazil seems mainly immune from external ideas, while India’s academic system, built on the British pattern and influenced by India’s own bureaucratic culture, does not look abroad for ideas about change.

English, as the dominant scientific language, has an impact in all of the BRIC countries, and it is a challenge for all but India, which from the beginning of its academic history has used English as the primary language of teaching and research. Following independence in 1947, Indian languages began to be used for teaching in some undergraduate colleges and a few universities. However, a majority of undergraduate courses and almost all graduate-level degrees are taught in English.

English is more problematical in the other BRIC countries. China and Russia have established a small number of courses and degree programs taught in English, in part to attract international students. China in particular has expanded the number of English-medium degrees, and at the top universities some courses are offered in English for domestic students. Brazil seems to lag somewhat behind in embracing English as a major theme in academic development.

The BRICs, with the partial exception of Brazil, are emphasizing the importance of their academics publishing in English, in recognized international scientific journals, and in general participating in the global scientific community. Promotion and prestige are increasingly related to publication, and many Chinese universities offer special payments to their academics who publish in top international journals.

The balance between striving to achieve global recognition, on the one hand, and sustaining a national and regional academic culture on the other remains a dilemma for the BRICs. While they seek to join the academic superpowers, at the same time their own national academic systems require support and their regional influence deserves attention (Altbach and Salmi 2011).

The BRICs remain peripheral in the global knowledge system. China and India send the largest numbers of students in the world overseas for international study. Indeed, those two countries account for close to half of all global student mobility—and their numbers are likely to increase. All of the BRICs have a significant net outflow of students. Students studying in the BRIC countries by and large come from surrounding countries, emphasizing their roles as regional centers. Only China attracts significant numbers of international students, mostly from neighboring East Asian countries.

China, India, and Russia also contribute significantly to the global flow of academic talent, with many PhD graduates from these countries working elsewhere. This brain drain has been quite significant over several decades. Despite modestly improving rates of return and the new trend for some top academics and scientists to hold appointments in several countries, quite significant numbers of academics chose to leave these three countries. The causes are complex and include better working conditions, infrastructure, salaries abroad, academic atmosphere, academic freedom, and other factors.

Interesting variations among the four BRIC countries can be observed. Brazil has not suffered much of a brain drain, and the return rate for Brazilians who study abroad is quite high. An attractive academic environment in the top universities and competitive salaries, no doubt, contribute to the country’s higher education. Russia, which has a long and distinguished academic tradition, suffered dramatic financial cutbacks in higher education following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s. Numerous academics, including many distinguished scientists, left the country, and others quit the universities to start different careers. Only recently has the government recognized the need to rebuild the academic system. Funds have been invested in research universities and in several programs to improve the academic system, although salaries remain largely unattractive. China has implemented several programs to lure back top academics, who returned to China with improved salaries and working conditions. These programs have been modestly successful. India has not recognized its academic brain drain and has no programs in place to lure Indian academics back, although many Indians in various technology fields have returned to the booming high-tech sector—but not to the universities.

The BRIC countries thus occupy an anomalous academic terrain. They are at the same time large, growing, and increasingly powerful academic systems and still striving to occupy a more important global position. In many respects, they remain gigantic peripheries (Altbach 1993).

Massification as the underlying reality

The expansion of enrollments has been the key reality of global higher education in the last half of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century (Altbach, Reisberg, and Rumbley 2010). The “logic” of massification has affected all countries, resulting in increased access to higher education, greater importance of academic credentials for employment and social mobility, and the centrality of higher education in increasingly knowledge-based economies.

Table 1.1 Total and gross enrollment, 2009

Country | Total enrollment | Gross enrollment ratio |

Brazil | 6, 115, 138 | 36a |

China | 29, 295, 841 | 24 |

India | 18, 648, 923 | 16 |

Russian Federation | 9, 330, 115 | 76 |

United States | 19, 102, 814 | 89 |

Notes:a Gross enrollment ratio for Brazil was not available from UNESCO Statistics. The number was retrieved from Trading Economics, which used data from the World Bank.

Sources: UNESCO Institute of Statistics; Brazil gross enrollment ratio: Trading Economics.

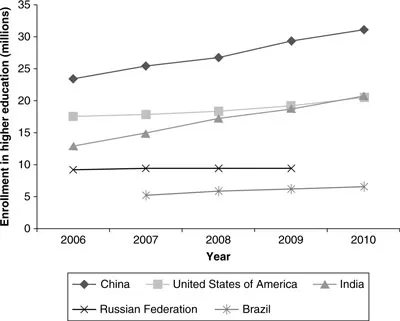

China and India have experienced massive growth in the past two decades and, in fact, will account for more than half the world’s enrollment expansion by 2050. Brazil, which had no universities until 1920, began to rapidly expand its enrollments later than the others. Table 1.1 shows current enrollments for the four BRIC countries and includes the United States for comparison.

In 2012, the BRIC countries and the United States have the five largest enrollments in higher education, and by 2008 the five countries, combined, accounted for 48 per cent of the world’s enrollment in higher education (see Figure 1.1). In terms of enrollment, China and India are now among the world’s three largest academic systems, and India will soon move into second place. Brazil ranks in fifth position and will no doubt move up the charts in the coming years. Russia will probably experience little enrollment expansion. The reason for the inevitability of expansion in China, India, and Brazil is, of course, the fact that they currently enroll, by international standards, a modest percentage of the relevant age cohort—in the case of India only 16 per cent, while China serves 24 per cent, and Brazil 36 per cent. Russia, in contrast, enrolls 75 per cent—similar to most economically developed countries.

Rapid massification produces some inevitable results—including an overall deterioration in the quality of higher education. This does not mean that the top part of academe becomes worse, but the average quality, measured by virtually any criteria, does go down. For example, 38 per cent of those teaching in postsecondary education in China have only a bachelor’s degree, although the proportions of academics with at least a master’s degree are much higher in the other BRIC nations. The average quality of students entering postsecondary education declines, at the same time that competition for places in the top universities increases. The phenomenon occurs because a larger number of more modestly qualified students are entering the bottom tier of universities, while competition for the limited number of places at the top-ranking universities is greater as applicants are aware of the quality and prestige variations among universities. Per-student funding also declines as numbers increase, and governments do not allocate sufficient funding to maintain quality for larger numbers. Thus, academic systems become more differentiated, either by plan or by the forces of the market— with the emergence of a small top tier of universities, alongside a much larger group of institutions catering to students from a wide range of backgrounds and abilities.

Figure 1.1 Enrollment in higher education, BRICs and the United States, 2006–2010.

Sources: UNESCO Institute of Statistics; Brazil gross enrollment ratio: Trading Economics.

The fact is that none of the BRIC countries provide a reasonable standard of quality to students in the mass sector of postsecondary education. Each underinvests in this sector. As a partial result, the private sector has moved in to provide mass access, and its quality is often low. In China and Brazil, particularly, the academic qualifications of those teaching in the mass sector are inadequate, and part-time instructors are widely used. Dropout rates are high, and many graduates are deemed to be unemployable.

Few countries have been able to develop and sustain a well-defined higher education system that adequately supports mass enrollments and world-class research universities at the same time. The BRIC countries, each in its own way, have been grappling with this key challenge in the era of massification.

The challenge of funding

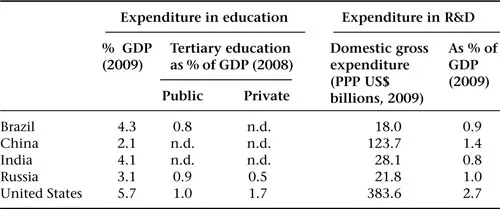

Postsecondary education everywhere faces significant financial challenges. The cost of catering to a larger and more diverse clientele is at the heart of the problem. Very few governments have the financial resources to fully support a comprehensive mass higher education system. The BRIC countries, due largely to their economic success in recent years, have the ability to provide more funds to higher education. Yet, despite clear needs, public investment remains relatively low when compared to that in developed countries. The average expenditure in education as a percentage of GDP for countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in general the wealthier nations, is 5.9 per cent (public and private combined); and the United States spends 7.2 per cent of GDP (public and private combined). Table 1.2 shows the BRICs range from 2.1 per cent (China) to 4.3 per cent (Brazil).

Table 1.2 Expenditure in education and research and development (R&D)

Note: n.d. = no data.

Sources: Percentage of expenditure in education as % of GDP: The Economist’s “Pocket World in Figures.” Expenditure in tertiary education as % of GDP: OECD Factbook, 2011. Expenditure in R&D: Batelle, R&D Magazine. Data from International Monetary Fund and Batelle.

Inadequate funding has significant implications throughout the academic system and makes it difficult, if not impossible, for postsecondary education to fulfill its goals and to serve the needs of individuals and society. The implications include low salaries for the academic profession and others working in higher education, a theme that will be discussed later in this essay. Quality suffers in many ways, with poor and often overcrowded facilities, a lack of support staff, outdated or nonexistent laboratories, substandard libraries and information technology, as well as limited access to internet-based resources, and other problems.

All of the BRIC countries have implemented special funding initiatives for higher education from public resources and have in the past several decades increased financial support for higher education. Yet, in all cases, the amounts allocated have been inadequate. In all four cases, base funding for higher education to pay for the expansion has been especially inadequate—resulting in poor quality of education, denial of access to some who see...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Notes on Contributors

- 1. The Prospects for the BRICs: The New Academic Superpowers?

- 2. Higher Education, the Academic Profession, and Economic Development in Brazil

- 3. Changing Realities: Russian Higher Education and the Academic Profession

- 4. India: Streamlining the Academic Profession for a Knowledge Economy

- 5. The Chinese Academic Profession: New Realities

- 6. The Changing American Academic Profession

- Index