eBook - ePub

Talent Management of Self-Initiated Expatriates

A Neglected Source of Global Talent

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Talent Management of Self-Initiated Expatriates

A Neglected Source of Global Talent

About this book

A collection of research papers about self-initiated expatriates and their experiences. As traditional talent management can no longer fulfil the needs of globally operating organisations, self-initiated expatriates have become an ever more important, albeit neglected source of the global talent flow.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Talent Management of Self-Initiated Expatriates by V. Vaiman, A. Haslberger, V. Vaiman,A. Haslberger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Self-Initiated Expatriates: A Neglected Source of the Global Talent Flow

Media, consultants, and academics in unison declare that there is a scarcity of qualified people on a global scale (Guthridge, Komm, & Lawson, 2008; Peiperl & Jonsen, 2007; Wooldridge, 2006). In the past, company-assigned expatriates (AEs) moved around to fill the gaps. Apparently this is no longer enough. While not a new phenomenon, a new and diverse breed of internationally mobile talent has caught the attention of researchers. These are academics and teachers going abroad on their own initiative to teach and learn themselves; they are people on time off to explore the world, be it right after school or as a mid-career break; they are professionals and experts independently seeking work in another country; and so on. In short they are self-initiated expatriates (SIEs). SIEs are a distinct group for several reasons: unlike AEs, SIEs initiate their move abroad themselves and do not wait to be asked or even prodded; unlike refugees, they are drawn by the opportunities and challenges of an international move and do not flee political strife, violence, or economic squalor; unlike immigrants, they intend to return home some time in the future and do not arrange to pull up roots for good. SIEs will provide at least a partial answer to the talent shortages bemoaned by experts. They are mobile, self-starting, and generally well educated. They are already an important factor in today’s global workforce (Tharenou & Caulfield, 2010) and, according to some observers, are likely to become evermore so (Peiperl & Jonsen, 2007).

Some experts believe that ‘traditional talent management no longer works’ (Cappelli, 2008: Part One). If people manage their careers independently, if talent retention is difficult, if the internal labour market can no longer serve the needs of the organisation, then talent management, traditionally focused on long-term planning and grooming high potentials internally, has to change. An evermore dynamic organisational environment undermines the predictability of demand for talent. Modern careers are becoming evermore independent of specific organisations (Arthur & Rousseau, 1996; Doherty, Brewster, Suutari, & Dickmann, 2008; Hall, 1996; Hall & Moss, 1998; Peiperl & Baruch, 1997). New answers to old problems, new sources of talent must be found. SIEs are one such source.

SIEs, besides providing much-needed talent, can also play a special role in internationally active organisations. They have a unique position in the host organisation between local employees and AEs. Their terms and conditions are usually based on local practices, yet their outlook is non-local. They may, therefore, be better able than AEs to serve as bridge builders and integrators, important roles that are hard to fill (cf. Adler, 2002; Stroh, Black, Mendenhall, & Gregersen, 2005). This may be in service to the organisation and its development (cf. Edström & Galbraith, 1977) or to enhance the cooperation between AEs and local employees (cf. Toh & DeNisi, 2005). SIEs, who work side by side with AEs, may in some respects feel the same as local employees. They, too, may experience comparatively smaller pay packages and a resulting envy in the face of AE’s more favourable terms and conditions (Toh & DeNisi, 2003). This creates a different HR management challenge.

Despite the importance of SIEs, only a small number of articles deal with this emerging field, which remains in a ‘pre-paradigm state of development’ much like international human resource management (HRM) was some 20 years ago (Black & Mendenhall, 1990, p. 113). The field still lacks, for example, a generally accepted definition of ‘self-initiated expatriate’ and similar terms. No clear delineations differentiate SIEs from company-assigned expatriates, on the one hand, nor SIEs and immigrants, on the other (Bergdolt, Margenfeld, & Andresen, 2012). This introductory chapter will provide an overview of recent publication activity related to SIEs. It will describe attempts at defining SIEs and demonstrate the pre-paradigm state of the field. After an overview of SIE numbers it will circumscribe a future agenda for SIE research. The introduction concludes with an overview of the chapters in this volume.

Publications about SIEs

Perhaps the first article addressing self-initiated work experience abroad was published in 1997 (Inkson, Arthur, Pringle, & Barry, 1997; cf. Suutari & Brewster, 2000). Since then the field has grown slowly, expanding at an accelerating pace only in recent years. A rough search for ‘self AND initiated AND expatriate’ produced 117 hits: the search was conducted, with a sole filter for ‘peer reviewed’, in the fields of title, author, full text, keyword, subject, and abstract in academic databases such EBSCOhost, JSTOR, ProQuest, and several others. The results for other search words using the same constraints are listed in Table 1.1. By sifting out mismatches, such as articles with little or nothing to do with SIEs and double listings, the searches returned some 70 plus articles. Of these, 30 plus referred to SIEs in the title. About two thirds were published in 2010 or later. Similarly, a search on amazon.com found one book on SIEs, which was published in the second half of 2012. The European Academy of Management 2012 conference had 10 papers with titles referring to both ‘self-initiated’ and expatriation, while the Academy of Management’s 2012 annual meeting listed two papers with such titles. If recent publication activity is any indication, the field of SIE studies will advance quickly over the next decade. One of the first questions to attend to is how to define SIEs.

Table 1.1 Rough literature search

Search terms | Number of hits |

Self AND initiated AND expatriate | 117 |

Self AND initiated AND expatriation | 110 |

Self AND propelled AND expatriate | 72 |

Self AND propelled AND expatriation | 16 |

Self AND directed AND expatriate | 98 |

Self AND directed AND expatriation | 98 |

Self AND directed AND travel | 131 |

Definitions

As mentioned earlier, the field lacks a generally accepted definition. Standard international definitions are too vague and, to date, most proposed definitions have flaws. The contributions to this volume use a variety of definitions underlining this issue. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Migrants Workers and their Families, which the General Assembly adopted in 1990 and entered into force in 2003, defines a migrant worker as ‘a person who is to be engaged, is engaged or has been engaged in a remunerated activity in a State of which he or she is not a national’ (General Assembly of the UN, 1990). This definition is broad and includes immigrants, refugees, voluntary expatriates whether employed or self-employed, and so on. For our purposes it is too broad because it includes immigrants and refugees. Bergdolt et al. (2012) reviewed over 200 definitions of ‘migrant’, ‘expatriate’, and ‘SIE’ (see also Andresen, Bergdolt, & Margenfeld, 2012). They see the term ‘migrant’ as encompassing expatriates, who in turn are defined as dependently employed. For the authors, SIEs are a subgroup of expatriates; they drive international assignments, making first contact with an employer abroad. This proposed definition, however, explicitly excludes self-employed persons, who, if counted as SIEs, might be a relevant source of global talent for companies. The authors’ definition fails to specify a minimum qualification level thus, in principle, including migrant farm labour, which is not relevant for global talent management. Andresen et al. (2012) investigated individual, organisational, and various other criteria in an empirically driven search for a definition. Their approach is clearly a step in the right direction. Previous studies under the SIE banner have cast a wide net including, for example, ‘overseas experience’ (OE) seekers of all ages (Inkson & Myers, 2003), young graduates (Tharenou, 2003), English teachers (Fu, Shaffer, & Harrison, 2005), academics (Richardson, 2006; Richardson & Mallon, 2005; Richardson & McKenna, 2006), volunteer workers (Hudson & Inkson, 2006), and business professionals (Fitzgerald & Howe-Walsh, 2008; Jokinen, Brewster, & Suutari, 2008; Lee, 2005; Suutari & Brewster, 2000).

The rough definition of SIEs underlying the contributions to this volume distinguishes at least these characteristics: initiated by the expatriate, voluntariness of the move, temporary nature intended even if open ended, and high skill level. This excludes refugees, immigrants, AEs, low- or unskilled labour. It includes the self-employed and individuals initiating an international assignment with their current employer.

Pre-paradigm state

The attention given to crafting a standard definition is one indicator of the pre-paradigm state of the field, as is the rather recent growth in publication activity on SIEs. Another is the methodological approach existing studies apply. The majority of articles on traditional expatriates use a quantitative methodology, while SIE studies split evenly between qualitative and quantitative methodologies, indicating a more exploratory state of play for SIEs, according to a recent metadata review of global careers research on company-assigned expatriates and SIEs (Shaffer, Kraimer, Chen, & Bolino, 2012). A special issue on the careers of skilled migrants, arguably a group that includes SIEs, includes an editorial calling the field under-theorised (Al Ariss, Koall, Özbilgin, & Suutari, 2012). The papers in this volume reflect the pre-paradigm state of SIE studies, with the majority applying a qualitative methodology. They use a wide array of theoretical models stemming not only from traditional expatriate studies but also from research on human capital and career studies to concepts of ethical consumerism.

A workshop at EURAM 2012, entitled ‘Self-initiated expatriation: A new pattern of international mobility’, stressed the novelty of the topic and hence its early stage of development. Befitting an emerging area of academic study the participants threw a wide net (see ‘An Agenda for the Future’ below) and also included many topics, which offer a comparison to more traditional forms of expatriation.

SIE numbers

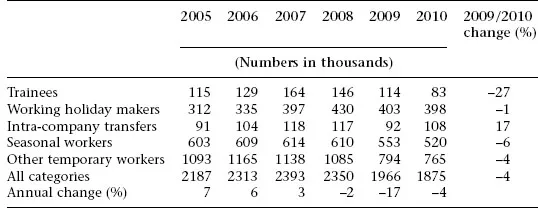

Comprehensive data on expatriates in general and SIEs in particular are hard to come by. One of the best sources is probably the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), which publishes an annual International Migration Outlook and special reports. In 2001, the 34 OECD countries1 had a total population of almost 1.07 billion, of whom just over 3% or almost 32.6 million were foreign-born non-citizens (Dumont & Lemaiître, 2005). The same year the global number of expatriates was just over 70 million (Dumont & Lemaiître, 2005), of which about 25% or 17.6 million were highly skilled (own calculation based on Dumont & Lemaiître, 2005). In 2010, a total of 5,274,850 foreigners moved into OECD countries (OECD, 2012a). The OECD data on temporary worker migration allow tentative conclusions about SIE numbers (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.2 Temporary worker migration in OECD countries, 2005–2010

Source: OECD, 2012b, p. 35.

There are at least 1.9 million temporary worker migrants in the OECD countries. The actual number may be higher because of incomplete coverage in data collection. The report emphasises a significant drop in 2009 as a result of the economic crisis followed by a further but only slight drop in 2010. Trainees and working holiday makers are both categories in which work is incidental. The former move particularly for the purpose of training, while the latter are more focused on tourism and cultural exchange. Working holiday makers are mostly young people who take off for up to one year (cf. Inkson & Myers, 2003). Intra-company transfers are the class that is closest to traditional or AEs. They represent ‘movements within the same company. Some are for permanent-type assignments, and not necessarily considered as or included in the figures for temporary work migration’ (OECD, 2012b, p. 36). Notably, this category excludes transfers within the European Union because of its free movement of labour. The report is moot on the question whether trainees and working holiday makers moving within the EU are counted. Seasonal workers include mainly low-skilled agricultural labour. Other temporary workers are a mixed category ‘including au pairs, researchers and short-term workers’ (OECD, 2012b, p. 36).

The OECD’s numbers provide only a rough idea about SIE numbers. Depending on the definition a significant portion, perhaps even most working holiday makers and trainees, may count as SIEs. Probably a minority of other temporary workers are also SIEs, while seasonal workers can be omitted because their numbers contain mostly low-skilled labour. Overall, the numbers indicate that SIEs make up a significant portion of the expatriate population, at least within OECD countries. Even if there were three uncounted within EU intra-company transfers for each one counted, their combined number would still be less than trainees and working holiday makers taken together. And there are an unknown number of researchers and short-term professionals from the other temporary workers category. Of course, a caveat is that working holiday makers and trainees are in incidental work that may be low skilled or, at least for the former, unrelated to any later career path.

An agenda for the future

It is clear that SIEs represent a significant part of the international talent pool about which we know relatively little as yet. Therefore, it is important to chart a course for future research. A good starting point is the above-mentioned workshop at EURAM 2012, which drew some 20 participants including recognised experts in international HRM and expatriate studies (Andersen et al., 2012). Their discussions resulted in a loose list of topics for further study, to which we added a few comments:

- De...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- 1 Self-Initiated Expatriates: A Neglected Source of the Global Talent Flow

- Part I

- Part II

- Index